Reconsiderations: The Book of The Dun Cow and The Book of Sorrows

One of the characteristics of a great book is that you can go back to it at different times in your life and get different things out of it. But then sometimes the reverse happens: you read a book before you’re ready. If you’re lucky, though, the book hangs around in the back of your mind, and eventually you pick it up again and find out what you weren’t able to grasp the first time around.

One of the characteristics of a great book is that you can go back to it at different times in your life and get different things out of it. But then sometimes the reverse happens: you read a book before you’re ready. If you’re lucky, though, the book hangs around in the back of your mind, and eventually you pick it up again and find out what you weren’t able to grasp the first time around.

When I was in elementary school, someone gave me a copy of The Book of the Dun Cow, by Walter Wangerin, Jr. I read it, but I didn’t particularly appreciate it. Many years later, I bought another copy, and was much more impressed. I also understood why I didn’t care for it as a child. Not long ago, I found a copy of the sequel The Book of Sorrows. Reading the books together I was impressed again.

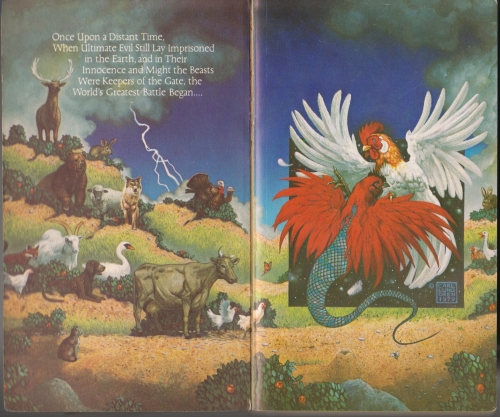

The books are an animal fantasy, set when “the earth was still fixed in the absolute center of the universe. It had not yet been cracked loose from that holy place, to be sent whirling — wild, helpless, and ignorant — among the blind stars. And the sun still traveled around the moored earth, so that days and nights belonged to the earth and to the creatures thereon, not to a ball of silent fire. The clouds were still considered to flow at a very great height, halfway between the moon and the waters below; and God still chose to walk among the clouds, striding, like a man who strides through his garden in the sweet evening.”

Humans have not yet been made, and the world is inhabited by animals, who talk and think. And they have a purpose, which is to act as Keepers against Wyrm, the evil that dwells in the heart of the earth and wants to ruin all creation. It is the connection between the animals — their community — that keeps Wyrm from rising. The two books describe two particularly vicious assaults by Wyrm against his keepers, and what happens to the animals as a result.

The main characters of the books are those animals led by Chauntecleer, a rooster. Roosters in this world have a key function; their crows divide the day, giving time shape and form and meaning. Their crows are named like prayers in a medieval monastery; compline, prime, vespers, and so on.

Chauntecleer is arrogant and proud, but a strong leader who protects his harem of hens and the other creatures that live around his Coop, including the self-sacrificing and comically depressed hound, Mundo Cani Dog, and the excitable but good-hearted John Wesley Weasel. But problems are arising elsewhere: Wyrm has troubled the dreams of an aging rooster named Senex, who makes a faustian deal and so produces an egg from himself. From the egg comes Cockatrice, who forcibly begets an army of basilisks on the hens of Senex’s coop.

The Book of the Dun Cow describes these events, and the resulting war between Chauntecleer’s animals and Cockatrice. The Book of Sorrows follows the aftermath, as Wyrm again schemes to attain his freedom. The books are similar, and feel like a unity, though they have their differences; The Book of the Dun Cow is terser, swifter, while The Book of Sorrows is darker, and less overtly dramatic.

The books are remarkable performances. The style is fluid, direct, and powerful. There’s an amazing range of tones in Wangerin’s language; simple, casual diction flavoured with Biblical echoes and unexpected allusions, shifting from one to another easily.

Here’s a passage from The Book of Sorrows:

“Nobody told John about grief! No, he couldn’t scream the aching out of him. It stays. No, he couldn’t fight nor murder nor slaughter the aching out of him; and though he scorched the battlefield that day, and though he killed a countless host, himself inspiring the Animals unto victory, he lay down that night still aching.”

You can see the Biblical resonance in phrasing like “a countless host,” or “unto victory.” But the dominant tone is direct and almost everyday: “Nobody told John about grief!” At the same time, there’s a music to the writing, using repetition and rhythm to build power.

You can see the Biblical resonance in phrasing like “a countless host,” or “unto victory.” But the dominant tone is direct and almost everyday: “Nobody told John about grief!” At the same time, there’s a music to the writing, using repetition and rhythm to build power.

It feels to me like the language of a good preacher, reaching out to his audience, drawing them in with rhetoric, with an almost hectoring insistence on his story. But the story isn’t a means to an end; the story is a thing in itself. It relates something the storyteller has learned, presenting felt truth in a form that solicits empathy if not understanding.

The books are Christian in sensibility and tone without necessarily being evangelical, in the sense of seeking converts. There’s an attitude to sacrifice, to the ransom paid to evil being the means of evil’s defeat, that I think is thematically Christian. God doesn’t show up in the books — indeed, Chauntecleer especially feels the absence of God powerfully — but His messenger, the mysterious Dun Cow who is seen on rare occasions, is fundamentally a figure of consolation who cannot give direct aid against Wyrm’s evil without sacrifice.

In a sense, the books are consolation literature themselves. They don’t consider the question of evil, do not try to establish why evil exists or try to justify the ways of God to man. They seem to me to be more concerned with the question of how to live in a fallen world. How, given that sorrow exists, to endure.

A Christian fantasy with talking animals sounds like Narnia, but these books are quite different. They’re tragedies, and books about how to deal with tragedy — with sorrow, with loss, with the death of children. There’s a bleakness in them that Glen Cook and Steven Erickson know not of.

Practically, though, the rules of the world seem sometime difficult to parse. There are no humans, but someone built the Coops that the chickens dwell in. Late in the first book, metal and leather weapons are used, and you can’t help but wonder where they came from, and what relation the leather in the weapons bears to the flesh of the Dun Cow. Above all, you wonder how hawks and wolves and cats relate to deer and mice; and this is to say nothing of the occasional over-humanising of the animals, as when a hen is said to smile (a nice trick for a creature with no lips).

I think all you can do is say that this is an unfallen world, and things were different then. Certainly there’s a sense of hierarchy to the animal behaviour that’s difficult to grasp. It evokes a simpler, structured world — a medieval world, in fact, and it’s worth knowing that the names of Chauntecleer and his true love Pertelote come from Chaucer’s Nun’s Priest’s Tale, just as the Dun Cow is a reference to a medieval Irish manuscript.

I think all you can do is say that this is an unfallen world, and things were different then. Certainly there’s a sense of hierarchy to the animal behaviour that’s difficult to grasp. It evokes a simpler, structured world — a medieval world, in fact, and it’s worth knowing that the names of Chauntecleer and his true love Pertelote come from Chaucer’s Nun’s Priest’s Tale, just as the Dun Cow is a reference to a medieval Irish manuscript.

Verbal echoes like this abound in the books — a bird with her tongue torn out cries “Jug jug tereu,” which is a reference to the cry of the nightingle in The Waste Land and in Elizabethan verse before that — but the medieval echoes, I think, are particularly significant.

The cosmology of the world is essentially medieval; the way the creatures relate to each other, and the way they think of themselves, is medieval. More specifically, the books present an idealised version of a medieval society

The medieval isn’t a problem; the idealisation is. The characters in the books easily accept the roles their society allots for them. Gender roles in particular are very traditional, sometimes to the point where one’s suspension of disbelief is threatened. Certainly you wonder if a world can plausibly claim to be unfallen if it’s narrow enough to exclude commanding females.

More broadly, I think the hierarchical structure of the world becomes difficult to relate to. The Book of the Dun Cow is clear about this; structure gives meaning. “Senex,” we’re told,

“however poorly he had ended his rule, had always remembered the canonical crows. He sang them, to be sure, in a disoriented manner; but he did sing them, keeping his animals that way, banding them, unifying them. But Cockatrice never crowed the canon. So under him the day lost its meaning and its direction, and the animals lost any sense of time or purpose.”

Purpose and structure, in other words, come from without. They come from God, and are given from him to the animals by the priestlike rooster. Cockatrice’s crime is a crime against cosmic order, and it has direct and necessarily tragic results for the animals; the solution is not the creation of a new order, but the re-imposition of the old one.

It might be easier to accept this if we could see something compelling in the characters of the roosters — if there was something remarkable about them, something that made them particularly fit for their duties. But there isn’t, that I can see. Senex is so old and obviously unfit he seems to have been set up to fail. And Chuantecleer, though a powerfully interesting character, is by no means a great leader. It’s not a surprise when he fails; it’s something you can see in him from the beginning, and while his flaws make him endearing and sympathetic, they do leave the reader wondering why nobody else is able to see them.

Still, whatever my qualms about their worldview, the books succeed as narratives, largely due to the truth of the character drawing. The animals are vivid personalities, who use language in distinctive ways, who make you believe in them and their passions. They’re emotionally affecting, characters that feel — and what they may feel may be simple, but they feel those things in their own ways. The springs that drive them to action are as complex as you’d find in many human beings (and more so than in certain people I can think of).

I think these are fine books, brilliantly written. I think the worldview that Wangerin uses results in contradictions in the world he writes, but most of them are contradictions theist thinkers have been struggling with for thousands of years. When I was a child, as an atheist urban-dweller, The Book of the Dun Cow didn’t mean much to me. I’m older now, and whether or not I’m any wiser I’m at least better able to relate to books written by people of different backgrounds and philosophies than my own; and whatever other good there may be in that, it’s worthwhile if only because it allows me to appreciate things that once were foreign to me.

Whatever criticisms I have of The Book of the Dun Cow and The Book of Sorrows, I can say that the writing is excellent. The prose is powerful, and occasionally soaring. There’s a complexity of reference and symbol that gives the actions of the characters weight and meaning. And the characters themselves are affecting, memorable, and true.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His blog is Hochelaga Depicta.