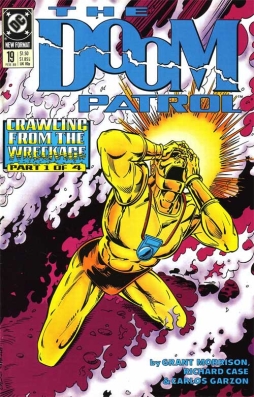

Crawling From the Wreckage: Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol

Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol needs no context to be enjoyed; it is its own strange, powerful creature. But describing the context of the thing helps to throw into relief the accomplishment of the work. And for those who may not know the comic, explaining what it came out of may help to explain what it is itself.

Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol needs no context to be enjoyed; it is its own strange, powerful creature. But describing the context of the thing helps to throw into relief the accomplishment of the work. And for those who may not know the comic, explaining what it came out of may help to explain what it is itself.

The Doom Patrol was a group of characters created for DC Comics in the early 60s, as the Silver Age of comics was getting underway; their first appearance, in My Greatest Adventure #80, hit the stands just before the first issue of Marvel’s X-Men. The two groups were famously similar: both were led by wheelchair-bound geniuses, and more significantly, both were a little stranger, a little darker, than other supergroups. The Patrol consisted of the Chief, the aforementioned scientific genius; Cliff Steele, AKA Robotman, whose brain had been transplanted into a metal body following a terrible accident; Negative Man, or Larry Trainor, a pilot wrapped in bandages who controlled a strange black ‘negative spirit’; and Elasti-Girl, Rita Farr, who could increase or decrease her size tremendously. Besides the similarity to the X-Men, the group vaguely resembled another Marvel team: the scientist leader, the orange-hued strongman (Robotman), the flying energy-controller (Negative Man), the woman who could disappear (by shrinking out of sight).

A little while ago, John O’Neill posted

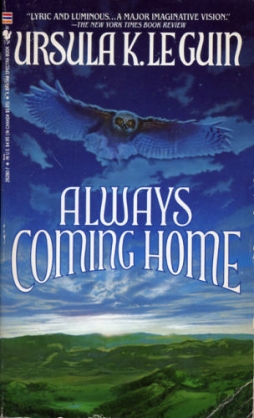

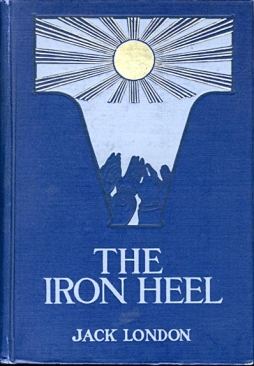

A little while ago, John O’Neill posted  These past two weeks I’ve found myself writing here about science fiction, or speculative fiction, as the literature of ideas. It seems to me that ‘the literature of ideas’ implies something other than what we normally find in sf; I feel that it suggests writing that uses ideas to establish the structure of a work, instead of relying on traditional narrative. I’ve found a couple of early examples in Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker and Jack London’s The Iron Heel. As a way to wrap up the discussion, I thought this week I’d look at a more recent example of what I mean by the literature of ideas: Ursula Le Guin’s Always Coming Home.

These past two weeks I’ve found myself writing here about science fiction, or speculative fiction, as the literature of ideas. It seems to me that ‘the literature of ideas’ implies something other than what we normally find in sf; I feel that it suggests writing that uses ideas to establish the structure of a work, instead of relying on traditional narrative. I’ve found a couple of early examples in Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker and Jack London’s The Iron Heel. As a way to wrap up the discussion, I thought this week I’d look at a more recent example of what I mean by the literature of ideas: Ursula Le Guin’s Always Coming Home. Last week I discussed Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker as an example of a true literature of ideas: a work structured not as a traditional narrative, with plot and character development as we know them, but instead built around the ideas that the work’s presenting, so that the book’s material is defined not by narrative but by the ideas at the core of its theme. As it happens, I recently stumbled across another example of this sort of thing.

Last week I discussed Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker as an example of a true literature of ideas: a work structured not as a traditional narrative, with plot and character development as we know them, but instead built around the ideas that the work’s presenting, so that the book’s material is defined not by narrative but by the ideas at the core of its theme. As it happens, I recently stumbled across another example of this sort of thing. It’s often said that science fiction (or speculative fiction, whatever term you prefer) is a ‘literature of ideas’. I’ve never been able to agree with that statement. In part, I feel much the same way

It’s often said that science fiction (or speculative fiction, whatever term you prefer) is a ‘literature of ideas’. I’ve never been able to agree with that statement. In part, I feel much the same way  While

While  This post is the latest installment of an ongoing discussion in the fantasy blogosphere, which I think has raised some interesting questions about fantasy and the fantastic tradition.

This post is the latest installment of an ongoing discussion in the fantasy blogosphere, which I think has raised some interesting questions about fantasy and the fantastic tradition. Reading The Fifth Head of Cerberus, I was struck by the way the book seemed eminently suited to the internet age. Never mind that it was written in the early 1970s. Like many of Gene Wolfe’s fictions, it’s a text whose nature is in harmony with the way the internet allows a text to be scrutinised; its depths, its meanings, its allusions — or at least some of them — can produce multiple readings, any of which can be valid, but which deepen the work as a whole the more of them you can think of and hold in your head at once. And can any one reader imagine as many different readings as a community of readers will produce?

Reading The Fifth Head of Cerberus, I was struck by the way the book seemed eminently suited to the internet age. Never mind that it was written in the early 1970s. Like many of Gene Wolfe’s fictions, it’s a text whose nature is in harmony with the way the internet allows a text to be scrutinised; its depths, its meanings, its allusions — or at least some of them — can produce multiple readings, any of which can be valid, but which deepen the work as a whole the more of them you can think of and hold in your head at once. And can any one reader imagine as many different readings as a community of readers will produce? I’ve always been fascinated by history, which is one reason why

I’ve always been fascinated by history, which is one reason why  This week I read an advance copy of the second book in Mark Chadbourn’s series of espionage-fantasy-adventure novels, Swords of Albion. The Scar-Crow Men begins with the first performance of Christopher Marlowe’s play Doctor Faustus, and the story of the novel and the story of Faust end up connecting in a number of ways. It got me thinking about Faust, and why the story of Faust has flourished in the centuries since Marlowe wrote, and how many different ideas about wizards there really are.

This week I read an advance copy of the second book in Mark Chadbourn’s series of espionage-fantasy-adventure novels, Swords of Albion. The Scar-Crow Men begins with the first performance of Christopher Marlowe’s play Doctor Faustus, and the story of the novel and the story of Faust end up connecting in a number of ways. It got me thinking about Faust, and why the story of Faust has flourished in the centuries since Marlowe wrote, and how many different ideas about wizards there really are.