William Blake and the Nature of Fantasy

Perhaps my favourite fantasy writing is arguably not fantasy at all. The epics and prophecies of William Blake certainly read like fantasy to many people, I think, albeit fantasy in a distinctive, unfamiliar form. But is the word appropriate? Blake himself was a visionary — he literally saw visions — and may well have believed that some at least of his writing was literally true. Does the definition of fantasy reside in the writer, or the reader? And how would Blake himself want his writing to be viewed?

Perhaps my favourite fantasy writing is arguably not fantasy at all. The epics and prophecies of William Blake certainly read like fantasy to many people, I think, albeit fantasy in a distinctive, unfamiliar form. But is the word appropriate? Blake himself was a visionary — he literally saw visions — and may well have believed that some at least of his writing was literally true. Does the definition of fantasy reside in the writer, or the reader? And how would Blake himself want his writing to be viewed?

Farah Mendlesohn, in her book Rhetorics of Fantasy, argued that the term ‘fantasy’ did not necessarily apply to the works of Latin American magic realist writers. As I understand her, she argues that the cultures of these writers are distinct from the culture that produced ‘fantasy fiction,’ and that the writers therefore stand in a different relationship of belief to the fiction. Magic realist texts “are not meant to act as genre text. Instead, the world from which the text was written is the primary world. It only becomes fantastical because we Anglo-American readers are outsiders. … Magic realism … is written with the sense of fading belief. If we are looking for some form of it, we need the literature of a similar culture, one in which the presence of other powers is a real and vibrant thing, even if it must exist alongside scientific rationalism.”

I don’t know whether what Mendlesohn describes is necessarily a cultural outlook, or whether it can be a personal one. She acknowledges it can apply to writing from the American South. But take John Crowley’s novel quartet The Solitudes, which seems like a North American piece of magic realism and which very carefully builds in explanations for its metaphysical elements — Crowley suggests that the world remakes itself on occasion, with different rules and a rewritten history each time; magic might have worked once, the books say, but when the world last changed, not only did magic stop working, but history itself was changed so that in fact magic now never has worked. Does one need to concern oneself with Crowley’s own philosophical positions before determining whether his writing is fantasy? (In fact, it’s a more complicated question than that; briefly, the characters are half-aware that they’re characters in a story, and the text itself unfolds aware of its nature as a text. Whether this makes it more fantastic or less is an interesting point, but not what I want to talk about here.)

Fantasy fiction is very often set either in the European Middle Ages, or in lands that are intentionally highly reminiscent of the Middle Ages in terms of technology and social structure. It is true that the use of European medieval settings is less common now than it has been, and also true that there have always been counter-examples. But it seems that much fantasy still relies on the European Middle Ages to define itself, one way or another. Sadly, one often has a sense that these backgrounds are not wholly thought-through; not realised as completely as they might be. The setting in a lot of fantasy, particularly I think in commercial fantasy fiction, seems to be a very generic Middle Ages in which medieval stereotypes mix with unexamined modern assumptions.

Fantasy fiction is very often set either in the European Middle Ages, or in lands that are intentionally highly reminiscent of the Middle Ages in terms of technology and social structure. It is true that the use of European medieval settings is less common now than it has been, and also true that there have always been counter-examples. But it seems that much fantasy still relies on the European Middle Ages to define itself, one way or another. Sadly, one often has a sense that these backgrounds are not wholly thought-through; not realised as completely as they might be. The setting in a lot of fantasy, particularly I think in commercial fantasy fiction, seems to be a very generic Middle Ages in which medieval stereotypes mix with unexamined modern assumptions. If I’m counting right, this marks my fifty-second post on Black Gate, which means this is effectively an anniversary. At any rate, it’s a good point to pause and reflect, I think. Writing here’s been a blast, from my first piece about Howden Smith’s collection of historical adventures Grey Maiden, up through last week’s essay on the origin story of Steve Ditko’s Doctor Strange. I’m eager to keep going, too; I feel like I’ve gotten better as a writer and critic from posting on this site, and I feel like I’ve begun to understand certain things about the nature of fantasy. I have to thank John O’Neill for inviting me to join his team, and Claire Cooney for her editing work; both John and Claire are accessible and generous with their time, and make posting here easy and fun. I also want to thank all the other bloggers who make this site, I feel, one of the best places on the web for fantasy fans. And especially I want to thank everyone who’s read and commented on my posts over the past year; I’ve been impressed with the level of responses I’ve seen, on my posts and others’, and fascinated by the conversations that’ve developed.

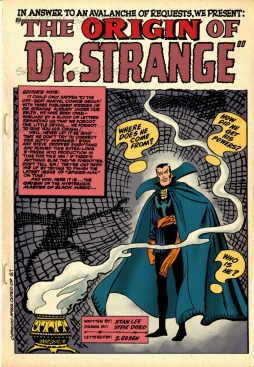

If I’m counting right, this marks my fifty-second post on Black Gate, which means this is effectively an anniversary. At any rate, it’s a good point to pause and reflect, I think. Writing here’s been a blast, from my first piece about Howden Smith’s collection of historical adventures Grey Maiden, up through last week’s essay on the origin story of Steve Ditko’s Doctor Strange. I’m eager to keep going, too; I feel like I’ve gotten better as a writer and critic from posting on this site, and I feel like I’ve begun to understand certain things about the nature of fantasy. I have to thank John O’Neill for inviting me to join his team, and Claire Cooney for her editing work; both John and Claire are accessible and generous with their time, and make posting here easy and fun. I also want to thank all the other bloggers who make this site, I feel, one of the best places on the web for fantasy fans. And especially I want to thank everyone who’s read and commented on my posts over the past year; I’ve been impressed with the level of responses I’ve seen, on my posts and others’, and fascinated by the conversations that’ve developed. One of my favourite Marvel Comics characters, certainly my favourite of all their big names, is Doctor Strange. Like most established Marvel characters, he’s been handled a lot of different ways over the course of time. I’d like to look back, and look closely, at one of the early tales that defined him most clearly — specifically, his origin story.

One of my favourite Marvel Comics characters, certainly my favourite of all their big names, is Doctor Strange. Like most established Marvel characters, he’s been handled a lot of different ways over the course of time. I’d like to look back, and look closely, at one of the early tales that defined him most clearly — specifically, his origin story. I recently

I recently  Marvel Comics has published some great works over the nearly fifty years since the company took its modern form with Fantastic Four #1. One thinks of the suberb superhero comics of Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, but there’s a lot more than that in Marvel’s vaults. William Patrick Maynard’s done some strong work on this web site looking back at some excellent series, and I encourage everyone to take a look at

Marvel Comics has published some great works over the nearly fifty years since the company took its modern form with Fantastic Four #1. One thinks of the suberb superhero comics of Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, but there’s a lot more than that in Marvel’s vaults. William Patrick Maynard’s done some strong work on this web site looking back at some excellent series, and I encourage everyone to take a look at  How to describe Matthew Flaming’s book The Kingdom of Ohio?

How to describe Matthew Flaming’s book The Kingdom of Ohio?  July 9, 2011 will be the hundredth anniversary of the birth of Mervyn Peake, the author of three remarkable fantasy novels: Titus Groan, Gormenghast, and Titus Alone. The books — published in 1946, 1950, and 1959 — form a series (along with the novella “Boy in Darkness,” which I have not read) following the early life of Titus Groan, Seventy-Seventh Earl of the immense castle called Gormenghast. Peake had intended to write a longer sequence of novels about Titus; he planned two more books, but the advent of Parkinson`s Disease made that impossible. A number of activities are being planned to commemorate Peake’s centenary, including the publication of a fourth Titus volume, Titus Awakes, written by Peake’s wife after his death in 1968.

July 9, 2011 will be the hundredth anniversary of the birth of Mervyn Peake, the author of three remarkable fantasy novels: Titus Groan, Gormenghast, and Titus Alone. The books — published in 1946, 1950, and 1959 — form a series (along with the novella “Boy in Darkness,” which I have not read) following the early life of Titus Groan, Seventy-Seventh Earl of the immense castle called Gormenghast. Peake had intended to write a longer sequence of novels about Titus; he planned two more books, but the advent of Parkinson`s Disease made that impossible. A number of activities are being planned to commemorate Peake’s centenary, including the publication of a fourth Titus volume, Titus Awakes, written by Peake’s wife after his death in 1968. Hope Mirrlees’ stunning 1926 novel Lud-in-the-Mist begins with the following epigraph:

Hope Mirrlees’ stunning 1926 novel Lud-in-the-Mist begins with the following epigraph: As a good Shakespearean, Kenneth Branagh understands fantasy. I think the movie Thor succeeds mostly because of what he as a director brings to the film, and what he’s able to get out of his cast. What’s missing seems to be what the script doesn’t give him — a larger world, memorable supporting characters, and a willingness to engage with the matter of fantasy.

As a good Shakespearean, Kenneth Branagh understands fantasy. I think the movie Thor succeeds mostly because of what he as a director brings to the film, and what he’s able to get out of his cast. What’s missing seems to be what the script doesn’t give him — a larger world, memorable supporting characters, and a willingness to engage with the matter of fantasy.