J.M. McDermott’s Never Knew Another

Never Knew Another

Never Knew Another

by J.M. McDermott

Night Shade Books (240pp, $14.99 USD, trade paperback February 2011)

Reviewed by Matthew David Surridge

J.M. McDermott’s third book, Never Knew Another, is a secondary-world fantasy tale told in a sparse yet elegant style, about hunters seeking dangerous magical prey — and also about two people drawing closer to each other without knowing it, despite having to hide their true natures from the world around them. Perspectives nest one inside another; the book’s always clear, but leaves much meaningfully unsaid, and effortlessly holds the voices of its characters in a delicate balance, allowing them to contrast with each other without any given one being overwhelmed. It’s a remarkable accomplishment, and a strong, unconventional beginning to a promising trilogy.

It starts with a pair of holy werewolves, following a trail to a human city they call Dogsland. The werewolves are hunting demons, or humans with demonic ancestry. Creatures with demons in their family tree are dangerous; their sweat is acidic, and their blood can wither plants, or make normal humans very sick indeed. It’s as though they’re radioactive, potentially causing illness and death around them even if they don’t consciously intend evil. The hunters see their task as a sacred duty. Their story, though, is effectively a frame for the main action; one of the hunters communes with the memories of a dead demon-descended man, searching through those recollections for hints of the whereabouts of others of his kind. The stories of that man, Jona Lord Joni, and of the others of his kind that he knows, provide the meat of the book.

Dying is easy, the old saw has it, but comedy … that’s hard. Only — what happens if we’re talking about a world in which miracles happen to order, and people come back to life whenever a priest wants? Dying suddenly isn’t quite so easy. But comedy, real comedy … that’s still pretty hard.

Dying is easy, the old saw has it, but comedy … that’s hard. Only — what happens if we’re talking about a world in which miracles happen to order, and people come back to life whenever a priest wants? Dying suddenly isn’t quite so easy. But comedy, real comedy … that’s still pretty hard. Last Friday was Friday the thirteenth. It was also Clark Ashton Smith’s birthday. In memory of that conjunction, I’d like to write a bit about Smith and his work. I have only a few thoughts about Smith’s prose style; Ryan Harvey’s excellent and insightful look at Smith’s fiction can be found in four parts,

Last Friday was Friday the thirteenth. It was also Clark Ashton Smith’s birthday. In memory of that conjunction, I’d like to write a bit about Smith and his work. I have only a few thoughts about Smith’s prose style; Ryan Harvey’s excellent and insightful look at Smith’s fiction can be found in four parts,  I’ve been in unwilling low-content mode for the past couple of weeks (question: what’s worse than getting the flu at Christmas? Answer: getting the flu along with a sinus infection). That’s meant I’ve had some time to read, which is good for a number of reasons. As it happens, though, one of the things I picked up to read left me wondering something I’ve wondered several times before: why do certain books pull me along, and compel me to read them, even when I think they’re not particularly good?

I’ve been in unwilling low-content mode for the past couple of weeks (question: what’s worse than getting the flu at Christmas? Answer: getting the flu along with a sinus infection). That’s meant I’ve had some time to read, which is good for a number of reasons. As it happens, though, one of the things I picked up to read left me wondering something I’ve wondered several times before: why do certain books pull me along, and compel me to read them, even when I think they’re not particularly good? There are two different stories about how it began.

There are two different stories about how it began. I’ve been a bit under the weather the past couple of weeks, which has been annoying for a number of reasons. For one thing, I was unable to get my thoughts in enough order to respond adequately to three pieces of writing I came across several days ago. Each piece on its own seemed to pose interesting questions, and collectively they raised what seemed to me to be related issues about how one reads, and why; and how and why one reads fantasy in particular.

I’ve been a bit under the weather the past couple of weeks, which has been annoying for a number of reasons. For one thing, I was unable to get my thoughts in enough order to respond adequately to three pieces of writing I came across several days ago. Each piece on its own seemed to pose interesting questions, and collectively they raised what seemed to me to be related issues about how one reads, and why; and how and why one reads fantasy in particular. Hal Duncan’s The Book of All Hours is a dazzling, fascinating, frustrating work. A duology consisting of 2005’s Vellum and 2007’s Ink, it plays with structure and story in powerful ways, while also seeming to fall back too easily into black-and-white absolutes and traditional forms. The oddity of the book is that although in some ways it appears radically new, in other ways, as one reads further into it, it comes to feel more and more familiar.

Hal Duncan’s The Book of All Hours is a dazzling, fascinating, frustrating work. A duology consisting of 2005’s Vellum and 2007’s Ink, it plays with structure and story in powerful ways, while also seeming to fall back too easily into black-and-white absolutes and traditional forms. The oddity of the book is that although in some ways it appears radically new, in other ways, as one reads further into it, it comes to feel more and more familiar. If you read a lot, you’ll soon find yourself drawn to writers who become personal favourites but who, unaccountably, go unrecognised by the wider world. A little while ago my girlfriend introduced me to a book by one of her own favourite writers, a woman named Joan North. I want to write about North here, because I was impressed by her work and I think she deserves to be better known.

If you read a lot, you’ll soon find yourself drawn to writers who become personal favourites but who, unaccountably, go unrecognised by the wider world. A little while ago my girlfriend introduced me to a book by one of her own favourite writers, a woman named Joan North. I want to write about North here, because I was impressed by her work and I think she deserves to be better known. Writing about Romanticism has gotten me started thinking about forms, and conventions, and how we read a story. To some extent I’ve come to feel that contemporary ways of reacting to narrative are more classical than romantic; they’re more to do with structure and form than with trusting the individual genius. It seems to me that many readers, and critics, have become used to looking for certain things in a story, and have come to think of stories that function in a different manner as necessarily defective rather than distinct. And I feel this is a pity, since if we can’t accept the strange works of genius that succeed in defiance of everything we think we know about storytelling, then our experience of story becomes diminished.

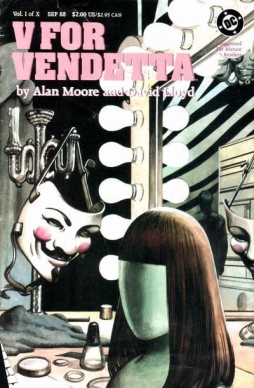

Writing about Romanticism has gotten me started thinking about forms, and conventions, and how we read a story. To some extent I’ve come to feel that contemporary ways of reacting to narrative are more classical than romantic; they’re more to do with structure and form than with trusting the individual genius. It seems to me that many readers, and critics, have become used to looking for certain things in a story, and have come to think of stories that function in a different manner as necessarily defective rather than distinct. And I feel this is a pity, since if we can’t accept the strange works of genius that succeed in defiance of everything we think we know about storytelling, then our experience of story becomes diminished.  I’m taking a bit of a break from the Romanticism and Fantasy posts, as I’ve got a few other things I’d like to write about. To start with, since I discussed Alan Moore’s Marvelman a few weeks ago, I thought I’d take a look now at V For Vendetta. V started as a series that ran, like Marvelman, in the early 80s in the black-and-white anthology magazine Warrior. Though the story was left incomplete when Warrior folded, in 1988 the series was republished in colour by DC Comics, and Moore and artist David Lloyd were able to finish it as they’d hoped. (Some spoilers for the book follow; also spoilers for Watchmen, oddly enough.)

I’m taking a bit of a break from the Romanticism and Fantasy posts, as I’ve got a few other things I’d like to write about. To start with, since I discussed Alan Moore’s Marvelman a few weeks ago, I thought I’d take a look now at V For Vendetta. V started as a series that ran, like Marvelman, in the early 80s in the black-and-white anthology magazine Warrior. Though the story was left incomplete when Warrior folded, in 1988 the series was republished in colour by DC Comics, and Moore and artist David Lloyd were able to finish it as they’d hoped. (Some spoilers for the book follow; also spoilers for Watchmen, oddly enough.)