The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith PART I: The Averoigne Chronicles

By Ryan Harvey

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

In the beginning, there was Clark Ashton Smith…

In the beginning, there was Clark Ashton Smith…

…in the end, there was Clark Ashton Smith.

Smith was a one-man literary movement, an alpha and omega unto himself. Although a major early fantasy innovator whom many later writers credit as an influence, he did not begin an ongoing trend in fantasy fiction as some other pioneers did. Contrariwise, he seems to have borrowed his style from almost no one. He was, and is, a unique and unclassifiable talent in the field of fantastic literature. His uniqueness accounts for how little he is published or read today, even though his name always finds its way into discussions of his two compatriots at the pulp magazine Weird Tales, H. P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard. But while they continue to find larger and larger readerships with mainstream editions of their work, Smith has fallen into limbo.

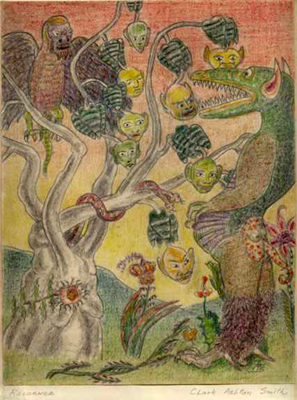

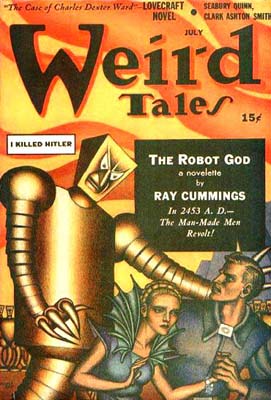

Clark Ashton Smith lived most of his life in Auburn, California, near the foothills of the Sierras in the placer mining region. Today the city of Auburn proudly celebrates its Gold Rush history in its beautifully maintained historic district. But the shade of the city’s greatest artist (not only in prose, but also in poetry, sculpture, and drawing; the illustration above is one of his works) remains elusive. Outside of the historic buildings and the gleaming city hall on its private hill, Auburn is a bland contemporary suburb of Sacramento, filled with traffic jams on the freeway, chain hotels, and strip malls packed with Targets, McDonalds, and Best Buys. Considering that Smith once wrote that “America’s worst enemy is not Bolshevism but its own rank and shameless commercialism,” I have no problem imagining what he might think of his hometown today.

On a visit to Auburn, I tried to dig up as much of Clark Ashton Smith as I could. The library keeps a collection of his rare volumes, the folks who run the used bookstores know a bit about his work, and the small residential street where his house once stood (burned down long ago) now bears his name: ‘Poet Smith.’ But otherwise you could hardly imagine a less congenial setting for a writer whom a recent anthology dubbed ‘The Emperor of Dreams.’

But dreams always transcend their surroundings; that is what makes them dreams. As I lay on my bed in the Auburn Motel 6 during a sweltering late spring evening, listening to teenagers on the street below argue about where they should get their pizza for the night, I flipped through the pages of a collection of Smith’s stories and marveled at the feeling of his prose filtering up from the ground where he spent most of his life. Even surrounded by the dull hum of an air conditioning and the deadening white light of the overhead lamp, and lying on a cheap paisley-pattern comforter, I could read Smith’s words and find myself in lands so removed from the ordinary, so enraptured with the power of language, and so intoxicated with transcendent peculiarity that everything within the reach of my senses vanished and surrendered to Smith’s enchantment.

There is a strange comfort in reading a special author whom you know so few other people have experienced. Ray Bradbury said it best: “Smith always seemed, to me anyway, a special writer for special tastes; his fame was lonely. Whether or nor it will ever be more than lonely, I cannot say. Every writer is special in some way, and those who are more than ordinarily special are either damned or lost along the way.” Knowing that they won’t damn Clark Ashton Smith, and that they are willing to recover what of his might be lost, gives his fans a sense of closeness to him.

However, it still seems tragic that such a talented and influential author should go so unknown today. The modern press, busy getting new books on the shelves to satiate readers who hunger only for fresh material, often lets the precious heritage of older fantasy literature slip away. Although Clark Ashton Smith’s writing will never have widespread appeal because of his ornate style, he should at least have a few paperbacks on the shelves of the local Barnes & Noble.

This series of four essays on the man whom H. P. Lovecraft once jocularly named in mock Egyptian “Klarkash-Ton” represent my contribution to spreading the mysteries of his particular religion: the wonder of words in arcane worlds.

The Word Dervishes of Klarkash-Ton

Clark Ashton Smith considered himself, before all else, a poet. He first made his literary name with his bizarre, cosmic verse. His fiction displays this origin at each opportunity. A poet expresses in concentrated form the resonance of the word and the rhythm of its placement. Likewise, Smith’s stories concentrate on the effect of the weaving of words; plot and character come a distant second in importance. To Smith, words were like the tricks, dips, and pirouettes of a dance routine. For most writers, to move pleasingly to the rhythms of the music of language is a significant achievement. But Smith filled his dances with arabesques, leaps and, jaw-dropping aerials. However, his tricks weren’t merely present to dazzle the audience; they fit with the strange music he had chosen, and their cumulative effect was to create a complete and seamless performance.

His best work does leave a strong emotional residue, but most of that comes from the thick brew of strange words that seem to dwell in the depths of a dictionary that no mortal has ever dared to fathom-except for the esteemed Mr. Smith. He does not tell a story so much as he invites the reader to experience sensations and emotions. The sensations are ancient, sometimes cosmic. The emotions are often unpleasant: decrepit horror, but more often loss and regret.

Because the concept of environment dominates all Clark Ashton Smith’s work, he avoided the use of series characters. Instead of basing his stories around a single protagonist, as Howard and most other pulp writers did, he based them around locations. Three of these fantasy locales formed a large chunk of his output: Zothique, Hyperborea, and Averoigne. In later installments of my survey of Smith’s fantasy works I will examine Zothique and Hyperborea (as well as his ‘mini-cycles’ about Poseidonis, Xiccarph, and Mars), but Averoigne needs the most immediate attention, since it has suffered surprising critical neglect.

Haunted Averoigne: Klarkash-Ton Meets the Real World

Haunted Averoigne: Klarkash-Ton Meets the Real World

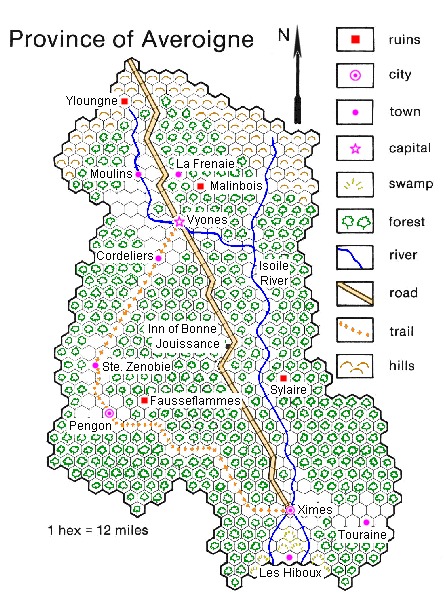

Averoigne lies in Southern France. Don’t look for it on any real world maps. It no longer exists, and perhaps never did. It has one major town, the walled city of Vyones, the seat of the Archbishop and home to a magnificent cathedral. The other important towns and villages are Ximes, Perigon, Frenâie, Sainte Zenobie, Moulins, Les Hiboux, and Touraine. The best road in the province travels between Vyones in the north and Ximes in the south. The Abbey of Perigon is the main source of learning, and the Abbot’s library contains an impressive collection of rare tomes. The river Isoile wends through the center of the province and empties out in a marsh to the south. The most important feature of Averoigne is the thick forest that covers most of the center of the province and gives the region its sinister repute. Other places in Averoigne with sorcerous reputations are the ruined castles of Fausseflammes and Ylrougne.

Smith sprinkles details about the province throughout the stories, although the most straightforward portrait appears in “The Maker of Gargoyles”:

At that time, the year of our Lord, 1138, Vyones was the principle town of the province of Averoigne. On two sides the great, shadow-haunted forest, a place of equivocal legends, of loups-garous and phantoms, approached to the very walls and flung its umbrage upon them at early forenoon and evening. On the other sides there lay cultivated fields, and gentle streams that meandered among willows or poplars, and roads that ran through an open plain to the high châteaux of noble lords and to regions beyond Averoigne.

The term ‘haunted’ is applied frequently to the region. For reasons unknown, Averoigne suffers from intrusions of supernatural creatures. Sorcery, although illegal as in all of medieval Europe, lurks in many places, even within the church. The people tolerate a few astrologers and dabblers in the magical arts, but many sorcerers have evil agendas and utilize power described as ‘diabolical’ and hold converse with infernal creatures.

One reason that Averoigne has received less exposure than Hyperborea and Zothique and Smith’s other supernormal creations is its mundane nature. Not only is Averoigne located in real history, it also plays host to already hoary fantasy and horror concepts: vampires, werewolves, spooky forests, time-travel, and witches. Smith’s description of the haunted woods of the province could match any medieval villager’s fearful rumors about his own local forbidding forest:

…the gnarled and immemorial wood possessed an ill-repute among the peasantry. Somewhere in this wood there was the ruinous and haunted Château des Faussesflammes; and, also, there was a double tomb with which the Sieur Hugh du Malinbois and his chatelaine, who were notorious for sorcery in their time, had lain unconsecrated for more than two hundred years. Of these, and their phantoms, there were grisly tales; and there were stories of loup-garous [werewolves] and goblins, of fays and devils and vampires that infested Averoigne. But these tales Gerard had given little heed, considering it improbable that such creatures would fare abroad in open daylight. (“A Rendezvous in Averoigne”)

Compare this to some of Smith’s other fantasy cycles: In Hyperborea an ordinary merchant can have the name Avoosl Wuthoqquan, and a lost solider named Ralibar Vooz can meet a succession of grotesque gods with names like Tsathoggua and Atlach-Nacha. In Zothique, starting your name with two ‘M’s, like Mmatmuor, and raising an army of the dead just for the hell of it aren’t considered unusual. Meanwhile, in Averoigne a man named Gerard gets lost in the woods and meets some vampires. No wonder this medieval French province often drops off the ‘weirdness scale’ that people use to judge the works of Clark Ashton Smith.

In terms of memorable tales, the Averoigne cycle also falls behind Hyperborea et al. Zothique was Smith’s strongest artistic series, while its connections to H. P. Lovecraft’s ‘Mythos’ and its cynical humor have made Hyperborea much more interesting to fans. Averoigne, however, does have a quality other of the author’s stories lack: a familiar setting. When the weird occurs in Averoigne, it has a greater impact because it happens in a realistic, naturalistic environment. Perhaps because of this connection to the real world, Averoigne often features more earthy human emotions, in particular love and its corollary, lust. Romance takes a greater role in the Averoigne stories than it does anywhere else in the Smith canon, and in places a genuine feel of courtly love appears (leavened with doses of lust, of course). “The Enchantress of Sylaire” and “The Holiness of Azédarac” champion love over other forces. On the flip side of romance, lust dominates “The End of the Story,” “The Satyr,” and has hideous repercussions in “The Maker of Gargoyles” and “Mother of Toads.”

Smith also uses the historical setting to engage in religious satire. A number of his other stories, particularly those set in Hyperborea, have satiric-edged humor; but Averoigne provides an actual target: the medieval Catholic Church. The priests of Averoigne come across as an underwhelming force that cannot cope effectively with the horrors and magic of Averoigne. Smith takes pleasure in subjecting the clergy to debauchery and sinister magic that shifts their worldview upside down: “The Colossus of Ylourgne” and “The Disinterment of Venus” take sharp slashes at the clergy’s myopia and helplessness. In one of the most intelligent of the stories, “The Beast of Averoigne,” religion and science meet each other, and religion comes up dangerously short.

The medieval milieu nudges the Averoigne cycle into the familiar realm of heroic fantasy. Smith never wrote pure epic fantasy or sword-and-sorcery, but with stories like “The Colossus of Ylourgne,” “The Holiness of Azédarac,” and “The Enchantress of Sylaire,” he came quite close. Few writers have overtly imitated Smith’s mixture of science/fantasy/horror from his Zothique, Martian, and other planetary tales (Jack Vance excepted), but the werewolf-infested woods and vampire-haunted castles of Averoigne presage countless later dark fantasies set in medieval locations.

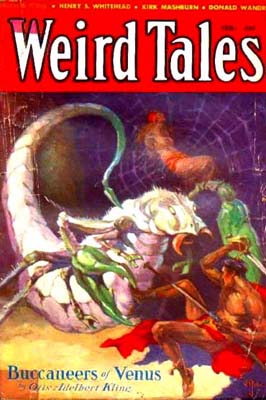

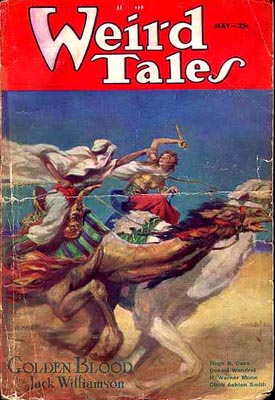

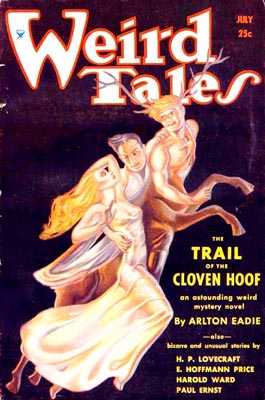

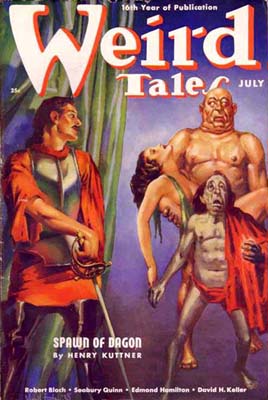

Smith completed eleven Averoigne stories, of which all but one appeared in Weird Tales during his lifetime. In the following overview, I have placed the stories in the order that Smith arranged them in his “Black Book,” a chronicle he kept of his short fiction. Smith wanted the Averoigne stories published in book forum as The Averoigne Chronicles, although it is unclear if this is the exact order he wanted them presented (they fall roughly into the order of composition). The only completed story he excluded from the list is “The Enchantress of Sylaire,” which he wrote during a later phase in his career. I have placed it at the end, where I believe the author himself might have slotted it. Smith also included in his list titles for which only synopses exist, and I have placed these at the end of this hypothetical The Averoigne Chronicles as a form of “appendices.”

The Averoigne Chronicles

“The End of the Story”

“The End of the Story”

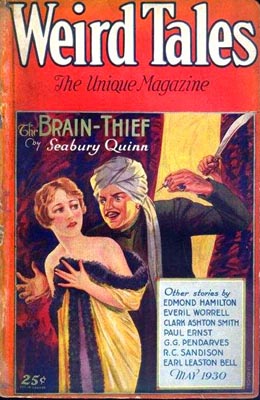

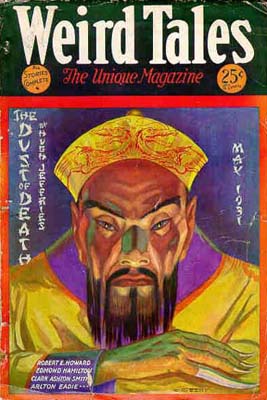

First published in Weird Tales, May 1930.

Smith nominally dates this story as occurring in 1787, making it the only Averoigne story to take place outside of the Middle Ages or the early Renaissance. However, the historical setting matters little, and nothing distinguishes it from the Averoigne of earlier years.

This first story set the unusual tone for the rest of the Averoigne chronicles: supernatural horror tempered with romance and sexuality, with a few hints of religious satire. Superficially, “The End of the Story” is a horror tale that adheres to a familiar storyline: an antiquarian, in this case a young law student named Christophe Morand, finds a forbidden old volume of lore that tempts him into the clutches of an ancient evil. This plot structure appeared repeatedly in the horror works of M. R. James and H. P. Lovecraft. Yet nothing horrific ever appears before the eyes of narrator Christophe, at least not that he lives to record. For him, this is a love story. The dark hints of what may dwell beneath the Château of Fausseflammes and Abbot Hilaire’s revelation about the true nature of the exquisite lady Nycea are at worst mere annoyances to Christophe and at best an urge to uncover more. Smith’s writing centers on the beautiful, idyllic, and tragically vanished instead of the grotesque; the scenes of Christophe emerging into the illusionary world of Nycea have a Hellenistic exoticism, and Christophe’s attraction to Nycea feels genuine instead of the demonic delusion that the stuffy abbot Hilaire insists it is.

Christophe strives to know ‘the end of the story’ he finds in the forbidden book of the Abbey of Perigon, but ironically we never discover the end of his story-although we can certainly guess it. Smith used a similar device of a man who escapes a horrible fate, only to find himself willfully driven into its clutches again — with unseen results — in his Martian story, “The Vault of the Yoh-Vombis.” Lovecraft’s “The Shadow over Innsmouth” has a similar reversal coda.

This is the only place in the Averoigne cycle where the clergy appears to wield any power against supernatural evil. Smith later portrays priests, monks, and bishops as either helpless aesthetes who turn every problem over to God, or else as cynical co-conspirators with dark forces. Abbot Hilaire successfully repels a vampire with holy water, but in “The Colossus of Ylourgne” demonic figures actually seize sacred implements and beat the monks with them in a mocking turnabout. Although the Averoigne stories use Judeo-Christian epithets for evil forces, Smith gives no proof of the existence of supreme deities of either good or evil.

“The Satyr”

“The Satyr”

First published in Genius Loci (Arkham House, 1948)

This is the shortest of the Averoigne chronicles and never appeared in the pages of Weird Tales, probably because of the hints of carnal lust and sexuality that underlie the appearance of a lecherous Pan-like figure and a forest with ‘obscene’ shapes that ignites passionate feelings between a pair of adulterous lovers. The Arthur Machen novella The Great God Pan and short story “The White People” may have influenced Smith, but his story again has the aura of courtly romance that clings peculiarly to Averoigne, and therefore a sense of genuine horror never blooms. The touches of genuine romance between the couple are the spark of this otherwise simple and quick fable.

Smith wrote an alternate ending to the story with a gruesome and even more sexual outcome. He cut it, perhaps, to make it more saleable (and apparently failed). The variant conclusion reads marginally better, since it combines the sex and violence inherent in the nature of Pan.

“A Rendezvous in Averoigne”

“A Rendezvous in Averoigne”

First published in Weird Tales, April/May 1931

This story bequeathed its name to a 1988 Arkham House collection of Smith’s stories and has seen more reprints than any of the other Averoigne tales, most likely because it deals with a standard monster with which most readers are familiar: the vampire. The traditional medieval European backdrop of Averoigne allowed Smith to utilize the customary monsters of fable more than in his more supermundane settings: aside from vampires, satyrs, gargoyles, and werewolves all make appearances. Fans of the writer’s stranger inventions might find this story too familiar and simplistic, but the magic of his prose still weaves an ensnaring web around the standard plotting.

A romantic tryst provides the catalyst to lure a troubadour named Gerard into the forest of Averoigne and to a mysterious castle. The castle’s tenants, Sieur de Malinbois and his chatelaine Agathe, heap hospitality on Gerard, his lover Fleurette, and her two servants, but a dim memory of the legend of two foul long-dead sorcerers with similar names makes Gerard believe that his hosts have something malign planned. The rest of the tale resorts to the vampire cliches of red marks on necks, a hidden tomb, a stake in the heart, and waving holy objects. Stylistically however, this is one of the most beautifully readable of the stories, walking the border between the lighthearted romantic ambitions of Gerard to rescue his beloved Fleurette and the eerie depiction of the mysterious castle of Sieur de Malinbois, where flames are still as “tapers that burn for the dead in a windless vault,” and from the stifling air creeps “forth a mustiness of hidden vaults and embalmed centurial corruption.”

“The Maker of Gargoyles”

“The Maker of Gargoyles”

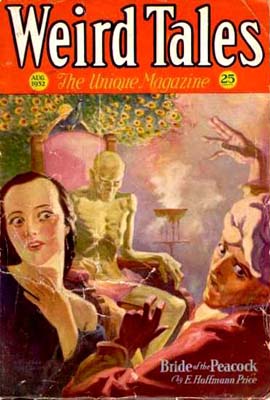

First published in Weird Tales, August 1932

In Averoigne there’s love, and then there’s lust. “The Maker of Gargoyles” has a surprising amount of the latter for a Weird Tales story, considering the truncation of Smith’s later “Mother of Toads” and editor Farnsworth Wright’s dislike of Robert E. Howard’s rapine-minded “The Frost Giant’s Daughter.” Taking psychoanalysis into his mythical region of France, Smith turns the hatred and lust of an unpleasant stonemason in the city of Vyones into two stone gargoyles that come to life and terrorize the population at night. Readers can take it as a straightforward horror story about a man who gets his comeuppance from his own creations, but the sexual content — again described in ‘saturnine’ and ‘satyr’ terms — makes it stand out. Smith also maintains good suspense in the finale.

“The Holiness of Azédarac”

“The Holiness of Azédarac”

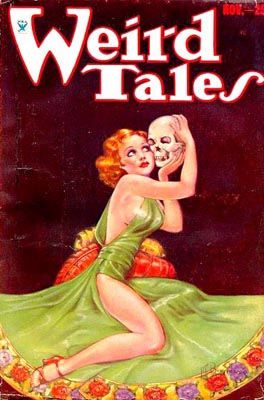

First published in Weird Tales, November 1933

This story has more humor than usual for a Smith’s prose (outside of the sardonic comedy of the Hyperborea series). He takes many satiric jabs, mostly at religion, but also at himself and his fellow correspondent from Weird Tales. Villain Azédarac is a comic sorcerer who rants about his devilish contacts like a name-dropper at a Hollywood party. The first few pages contain a cornucopia of weird gods, some borrowed from Lovecraft and Howard: “By the Ram with a Thousand Ewes! By the tail of Dagon and the Horns of Derecto!” On that note, the rest of the story reads something like a high romantic lark, and along with “The Enchantress of Sylaire” is the cheeriest of the stories; indeed, it ranks as one of brightest pieces that Smith wrote, overcoming his customary pessimism. He suggests that love is the ultimate retreat, even when all else fails, and all the crimes of horrible men mean nothing when you have a pair of loving and lusting arms wrapped around you.

The story takes a non-science-fiction approach to time travel. Azédarac, Bishop of Ximes and a diabolical sorcerer who has covered up his demonic rituals for years, uses his magic to send the monk who can expose his activities backwards in time seven hundred years to 475 C.E. There the poor monk finds unexpected help — and even more unexpected romance — from a pagan sorceress. This plot contains tropes appropriate to heroic fantasy: An evil sorcerer sends an assassin to get rid of a spy, a band of pagans tries to sacrifice the hero, there’s a scene in a rough-and-tumble tavern, and the heroine is a bewitching sorceress. Smith clearly takes the side of paganism and its unbridled sexuality over the strict mores of medieval Catholicism. The story’s sarcastic title and the character of Azédarac are also satiric shots at the church. Azédarac mostly serves a comic purpose. He rants ridiculously with a froth of demonic names bubbling from his lips, but he seems more like a low-level office bureaucrat who’s afraid his manager will discover he has started embezzling from the company picnic fund. Compare him to the sorcerer Nathaire in “The Colossus of Ylourgne,” whom Smith portrays with maximum menace and minimum irony.

“The Colossus of Ylourgne”

“The Colossus of Ylourgne”

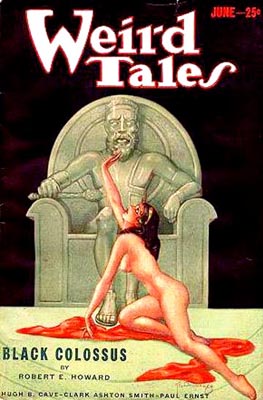

First published in Weird Tales, June 1933

This novelette is among the longest works that Smith published, running over 14,000 words, and in it the author achieves a near masterful epic of dark fantasy. Grisly images of necromancy, tomb-born terror, and gruesome destruction appear throughout, but instead of Grand Guignol horror, the end result is a heroic fantasy adventure — and close to sword-and-sorcery in the modern sense. If hero Gaspard du Nord, one of the few examples of a truly heroic character in Smith’s fiction, had picked up a sword at some point, “The Colossus of Ylourgne” would immediately qualify as sword-and-sorcery. There are striking similarities between it and Robert E. Howard’s then-emerging fantasy stories taking place in mythic pre-histories. The mix of Smith’s dark word magic with the heroic adventure make this one of his prose masterpieces and the jewel in the crown of Averoigne.

Given the longer length of the piece, Smith weaves a more intricate plot than usual and uses the template of a hero going against an evil sorcerer with a super-villain scheme. In 1281, the ailing necromancer Nathaire flees from the city of Vyones and plots ghastly vengeance from the ruined castle of Ylourgne before he dies. Gaspard du Nord, Nathaire’s former disciple, learns from his visitation to Ylourgne that Nathaire has summoned fresh corpses from all over Averoigne to serve as raw material for the making of a one hundred foot-tall dead body into which he will transfer his spirit…and then flatten all of Averoigne. It falls on du Nord to find a way to stop him.

Smith has more going on here than an exciting adventure and the lure of necromantic imagery (in which he indulges with delightful gluttony). The religious satire that weaves through the Averoigne cycle reaches its apotheosis here. Nathaire, in the form of the Colossus, vents his anger predominantly against the clergy and their icons, who can do nothing but pray hopelessly or flee. The Colossus looms as a titanic blasphemy that holds dominance over the symbols of Christianity, and it only falls to the forces of another wielder of forbidden magic, who ironically posts himself on the top of the Cathedral of Vyones to face his adversary.

“The Colossus of Ylourgne” also contains a rare mention of the events in another story. Gaspard du Nord, while climbing up into Vyones Cathedral, hides behind a gargoyle with features identical to the lustful stone carving that tormented the city over a hundred and fifty years ago in “The Maker of Gargoyles.”

“The Mandrakes”

“The Mandrakes”

First published in Weird Tales, February 1933

From the epic tale of the Colossus, Smith dives down to the simple fable of “The Mandrakes,” which resembles Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Black Cat.” It’s a short and unremarkable story about a sorcerer specializing in love potions who murders his wife and finds strangely feminine-shaped mandrakes growing over her hidden grave. Even Smith’s trademark writing style feels stale and underused, but the link between lust and violence and the theme of the souring of love are further examples of the earthy opportunities that the Averoigne setting offered to the writer.

“The Beast of Averoigne”

“The Beast of Averoigne”

Shorter version first published in Weird Tales, May 1933

Science fiction lands in Averoigne. Smith takes the alien invasion plot and drops it into the Middle Ages, where religion has no ability to comprehend it except in hoary diabolical terms and can do nothing against it. Only a budding scientist — still cursed with the terms “sorcerer” and “astrologer” — can hope to achieve anything. The similarities to “The Colossus of Ylourgne” show up immediately, but “The Beast of Averoigne” places itself more firmly in the science-fiction realm. Smith also experiments with a three-part narrative that might have taken inspiration from H. P. Lovecraft’s similarly divided “The Call of Cthulhu.”

Three different documents tell the story of coming of the baleful Beast of Averoigne in the year 1369. Gerome, a monk of the abbey of Perigon (already explored twice in previous stories), writes an account of his first meeting with the bizarre, snake-like creature that appears in conjunction with a comet in the sky and begins a reign of terror. A letter from the Abbot of Perigon, Theophile, to his niece in a convent relates the further depredations of the creature across the countryside; the Abbot voices his own doubts about his mind. Finally, the sorcerer-astrologer Luc Le Chaudronnier writes a statement about his effort to kill the Beast — which he has come to recognize is a creature not from the Earth — with the power of Ring of Eibon, a artifact which (Smith hints) contains another extraterrestrial entity of great power.

At the finale, Luc le Chaudronnier comes close to a true understanding of the identity of the Beast of Averoigne when he breaks free from the bond of the terrestrial thinking and its conception of religious good and evil:

Indeed, it were well that none should believe [this] story: for strange abominations pass evermore between earth and moon and athwart the galaxies; and the gulf is haunted by that which it were madness for men to know. Unnameable things have come to us in alien horror, and shall come again. And the evil of the stars is not as the evil of the earth.

The story cannot match “The Colossus of Ylourgne” in excitement, but the flawless use of three medieval voices and the fascinating collision between science and religion make this one of the most intriguing of the Averoigne chronicles.

Two version of the story exist. After Farnsworth Wright at Weird Tales rejected the original, Smith shortened it and dropped the triptych style, making the entire story the account of Luc Le Chaudronnier and integrating the earlier events into his testimony. The strongest elements of the original remain, but some of the complexity and vanishes. The loss of the individual voice of Abbot Theophile in his letter to his sister takes away the specter of personal tragedy. However, comparing the two versions does give an interesting picture of Smith’s revision process and which elements he chose to highlight and which to discard.

“The Disinterment of Venus”

“The Disinterment of Venus”

First published in Weird Tales, July 1934

This brief tale about the monks of Perigon (yes, them again) exhuming a lewd statue of Venus misses a number of opportunities for lusty, erotic satire, but Smith cannot take the blame for it: more explicit material would never have made it into print in the 1930s. That still cannot keep the reader from wondering what Smith could have done with the lustier elements if he had written them today, in the age of Anne Rice. The concept of an austere monastery falling into lecherous debauchery because of an erotic statue conjures up comic and horrific possibilities, but Smith can realize none of them under the publishing restraints of the time. A few of the monks spend a night drinking in a tavern, and that marks the limits of their carousing. Smith also plays briefly with the notion that the uncovered Venus represents not the classical goddess, but her earthier ‘chthonic’ form — the darker and bawdier part of Greek religion that rarely gets taught in high school.

“Mother of Toads”

“Mother of Toads”

First published in Weird Tales, July 1938, in an expurgated version.

Smith occasionally wrote gruesome and nauseous horror stories that prey on the readers’ senses. “The Mother of Toads,” like the similar freakish “The Seed from the Sepulchre,” works on a primarily revolting level. It’s the least likable of the Averoigne stories, but Smith’s ability to repulse is quite astonishing. It raises the lust theme of the Averoigne cycle to new heights: lust as a sickening, smothering murderer. It is no surprise that Weird Tales forced Smith to gut the story of its salacious and nasty sexual passages before it appeared in the magazine four years after he originally wrote it.

Mere Antoinette, a grotesque witch who lives in the southern swamps, seduces the young messenger-boy Pierre with one of her potions. The lascivious descriptions of the enchantment and lovemaking (slashed entirely from the Weird Tales version) have a slimy repugnance that equals anything Smith wrote:

This time he did not draw away but met her with hot, questing hands when she pressed heavily against him. Her limbs were cool and moist; her breasts yielded like the turf-mounds above a bog. Her body was white and wholly hairless; but here and there he found curious roughness…like those on the skin of a toad…that somehow sharpened his desire instead of repelling it.

She was so huge that his fingers barely joined behind her. His two hands, together, were equal only to the cupping of a single breast….The couch was rude and bare. But the flesh of the sorceress was like deep, luxurious cushions…

Mere Antoinette’s hideous revenge against Pierre’s eventual rejection of her feels tame compared to the descriptions of their amorous encounters!

But buried in this squeamish tale of magic-induced lewdness is a morsel of regret. Mere Antoinette, for all her repulsive physical characteristics, only wants the male attraction she knows she can never attain legitimately. Even though readers understand Pierre’s horror and denial of her, that cannot keep them from sympathizing with the ‘Mother of Toads’ in her loneliness.

“The Enchantress of Sylaire”

“The Enchantress of Sylaire”

First published in Weird Tales, July 1941

Clark Ashton Smith abruptly stopped writing fiction in 1935 after completing what he conceived of as his final Zothique tale, “The Last Hieroglyph.” He did periodically return to short fiction for the rest of his life (he died in 1961), and wrote additional stories both of Zothique and Hyperborea. But he wrote only one further entry in the Averoigne chronicles: this charming fantasy that crosses the borders of fairytale and sword-and-sorcery. At the end of the stories of Averoigne, love conquerors all, and a hero even draws a sword to defend his love against a slavering monster.

Young dreamer Anselme, with his devotion to beauty and books and romance, might stand for Clark Ashton Smith himself, or at least for many of his readers:

He seated himself on one of the boulders, musing on the strange happiness that had entered his life so unexpectedly. It was like one of the old romances, the tales of glamor and fantasy, that he had loved to read. Smiling, he remembered the gibes with which Dorothee des Flèches had expressed her disapproval of his taste for such reading-matter. What, he wondered, would Dorothee think now?

Anselme, after the pretty but haughty Dorothee rejects him, stumbles into the faery region of Sylaire and its lovely sorceress Sephora. The smitten Anselme helps Sephora defeat the werewolf Malachie du Marais, and at the end it is Anselme who must reject Dorothee for the true love of Sephora. The courtly romance is startling for Smith, as is the aspect of heroic fantasy, but a genuine optimism infuses the story and makes it the most likable of all the Averoigne chronicles and a fitting end for the cycle — whether Smith intended it as the last story or not. The final sentence is one of the most optimistic and romantic that the author ever wrote.

Fragments and Synopses

Fragments and Synopses

These eleven stories are the only completed works of Averoigne, but Smith kept extensive notes for others in his “Black Book.” Titles and synopses for other chronicles in the haunted French province survive: “The Sorceress of Averoigne,” “Queen of the Sabbat,” a sequel to “The Holiness of Azédarac” called “The Doom of Azédarac,” “The Oracle of Sadoqua,” and “The Werewolf of Averoigne.” The titles alone can quicken the heart of any reader of Clark Ashton Smith and give glimpses of the further wonders that might have emerged.

One of the synopses, “The Doom of Azédarac,” shows that Smith planned to further explore science-fiction concepts in Averoigne. The evil sorcerer-bishop Azédarac, on the verge of death, transports himself across dimensions to an alternate Averoigne and battles a version of himself in a duel. This story would have pushed the Averoigne cycle into the realms of hypothetical contemporary science.

The other intriguing synopsis that survives is “The Oracle of Sadoqua.” The outline takes place during the Roman occupation of Gaul, when Averoigne is known as “Averonia.” A Roman officer, Horatius, searches for his lost friend Galbius and finds him in a cave where the vapors of the breath of the pagan god Sadoqua (possibly a reference to the toad-god entity Tsathoggua in the Hyperborea stories) slowly devolve him into a hideous beast. Horatius also has an encounter with a beautiful pagan girl, indicating that Smith planned to also explore the romantic/erotic aspect of Averoigne in the story. The strong potential of a lengthy story early in Averoigne’s history, possibly explaining the origin of the weirdness of the region and containing doses of Lovecraftian horror, makes this another unfortunate case of an idea never coming to fruition.

Postscript

The complete Averoigne stories do not necessarily show Clark Ashton Smith at his bizarre best, and stories like “The Mandrakes” and “The Disinterment of Venus” will never rank as more than minor works. However, Averoigne’s conception as an historical environment makes it one of the most intriguing of Smith’s settings. And, perhaps, the one that would have worked the best if he had written it today. The stories show an earthy eroticism that begs to be cut loose from the censored constraints of the 1930s. In the erotic fantasy and dark horror market of today, Averoigne would make an ideal setting. The shadows of religious satire could also broaden in the modern writing scene. Perhaps the seeds of Averoigne were planted too early to flower properly.

Of course, fans of Klarkash-Ton might find it tempting to travel to Averoigne and create their own stories. I, myself, have often wondered about the succubi that Smith often mentions, and I have felt the sorcerous enchantment of the werewolf-haunted forests luring me to set my pen to paper and bring Averoigne back from the dusty parchments of the library of the Abbot of Perigon….

Part II of my continuing analysis of the series stories of Clark Ashton Smith turns to his “Book of Hyperborea,” and can be read here. You can read Part III in the series, “Tales of Zothique,” here, and Part IV, “Poseidonis, Mars, and Xiccarph,” here.

Our recent coverage of Clark Ashton Smith includes:

New Treasures: The End of the Story: The Collected Fantasies, Vol. 1 by Clark Ashton Smith

Vintage Treasures: The Timescape Clark Ashton Smith

The Shade of Klarkash-Ton by James Maliszewski

One Shot, One Story: Clark Ashton Smith by Thomas Parker

New Treasures: The Dark Eidolon and Other Fantasies by Clark Ashton Smith

The Crawling Horrors of Mars: Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis”

Deepest, Darkest Eden edited by Cody Goodfellow by Fletcher Vredenburgh

Adventures in Stealth Publishing: The Return of the Sorcerer

A Few Words on Clark Ashton Smith by Matthew David Surridge

The Unqualified Unique: The Daily Mail Interviews Me for Clark Ashton Smith’s 50th Morbid Anniversary by Ryan Harvey

Of Secret Worlds Incredible: A Psychedelic Journey into Clark Ashton Smith’s Poetic Masterpiece by John R. Fultz

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part I: The Averoigne Chronicles by Ryan Harvey

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part II: The Book of Hyperborea by Ryan Harvey

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part III: Tales of Zothique by Ryan Harvey

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part IV: Poseidonis, Mars, and Xiccarph by Ryan Harvey

I’ve had a TTRPG Averoigne campaign running for a number of years, set in the late 15c. It’s been a very successful effort. I’ve used all the flavors Smith used in his stories, with some extra doses of early French history influences, some of the ideas he had for future stories, and an expansion of the idea of baleful “fey” intrusions.

I’ve started reading the Averoigne cycle, just finished Colossus of Ylourgne. Awesome stories, enjoyed every one of them.