Fantasia 2017, Day 10, Part 1: Welcome to the Future (Napping Princess and Welcome to Wacken)

On Saturday, June 22, I reached Fantasia’s Hall Theatre before noon to see a screening of the anime Napping Princess (Hirune Hime: Shiranai Watashi no Monogatari), a story about dreams, technology, and the 2020 Olympics. After that, I had a short film showcase to see, then another feature. But before either of those, I planned to pass by the Fantasia Samsung VR 360D Experience, which, as the name implies, gives people the chance to experience VR by watching one of a selection of short films. I’d tried out the technology last year with a number of short fiction films; this time out there was something a little different, a half-hour documentary called Welcome to Wacken, about the legendary annual German metal festival. I wanted to see how the technology would handle the documentary form, especially since I had all the respect in the world for the filmmakers — it was directed by Sam Dunn, whose previous work included the seminal metal documentaries Headbanger’s Journey and Global Metal.

On Saturday, June 22, I reached Fantasia’s Hall Theatre before noon to see a screening of the anime Napping Princess (Hirune Hime: Shiranai Watashi no Monogatari), a story about dreams, technology, and the 2020 Olympics. After that, I had a short film showcase to see, then another feature. But before either of those, I planned to pass by the Fantasia Samsung VR 360D Experience, which, as the name implies, gives people the chance to experience VR by watching one of a selection of short films. I’d tried out the technology last year with a number of short fiction films; this time out there was something a little different, a half-hour documentary called Welcome to Wacken, about the legendary annual German metal festival. I wanted to see how the technology would handle the documentary form, especially since I had all the respect in the world for the filmmakers — it was directed by Sam Dunn, whose previous work included the seminal metal documentaries Headbanger’s Journey and Global Metal.

First, though, was Napping Princess (which, according to Wikipedia, is also known as Ancien and the Magic Tablet). Written and directed by Kenji Kamiyama, it begins in a dieselpunk otherworld called Heartland, where a daring princess named Ancien (voice of Mitsuki Takahara) seeks to regain her magic tablet with the help of an animated toy bear called Joy (Rie Kugimiya). A monster called the Colossus threatens Heartland, and Ancien’s father, whose palace is an enormous car factory like something out of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, has ordered her confined to a tower. But she escapes, meets a rebellious motorcycle-riding mechanic named Peach (Yôsuke Eguchi), and joins with him to counter the mysterious plot of the king’s sinister adviser (Arata Furuta) and the giant Colossus that emerges from the sea.

Until Ancien wakes up. In the world we view as real, a Japanese schoolgirl named Kokone is dreaming Ancien’s adventures. It’s 2020, and the Olympics are about to take place in Tokyo; Kokone and her father, Momotaro, a mechanic in the southern town of Okayama, wonder whether the autonomous cars Japan’s promised as a major part of the opening ceremonies will be ready on time (note that Okayama’s the setting for the original legend of Momotaro). But then Momotaro’s arrested and accused of corporate espionage against Shijima Motors, the company building the autonomous vehicles. Kokone has to escape Shijima’s representative, who bears an uncanny resemblance to the evil adviser of the king of Heartland, and work out the secrets contained in her father’s old tablet computer. What secret in his background has emerged? And how does it connect to the story of Heartland?

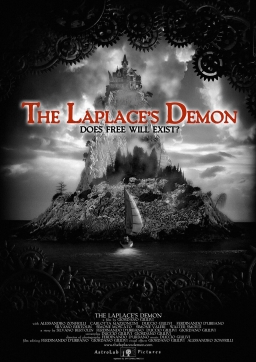

After two days off, I returned to Fantasia on June 21 fit, trim, and rested. Randomness defines my festival schedule — it happened that the previous two days had nothing I wanted to see. But that Friday afternoon I was looking forward to one of the most intriguing movies listed in Fantasia’s catalogue: The Laplace’s Demon, directed by Giordano Giulivi.

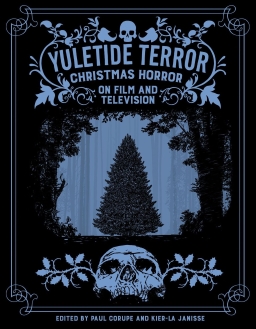

After two days off, I returned to Fantasia on June 21 fit, trim, and rested. Randomness defines my festival schedule — it happened that the previous two days had nothing I wanted to see. But that Friday afternoon I was looking forward to one of the most intriguing movies listed in Fantasia’s catalogue: The Laplace’s Demon, directed by Giordano Giulivi. As the year begins to burn itself out, as the light of summer gives way to long ghoul-ridden nights, as the cold grows a little more each day like spadefulls of earth slowly burying a coffin, what better time to think ahead to the horrors of Christmas? Not the pedestrian horrors of shopping and family, but the deeper terrors of knifemen and ghosts and dark-souled elves: the traditions of the season. Publisher Spectacular Optical’s planning a celebrate of exactly those kinds of Christmas frights, with their upcoming volume Yuletide Terror: Christmas Horror on Film and Television.

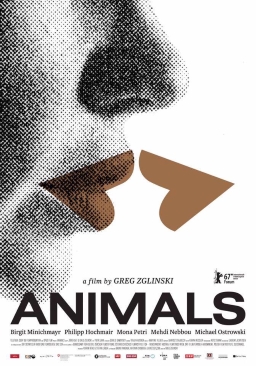

As the year begins to burn itself out, as the light of summer gives way to long ghoul-ridden nights, as the cold grows a little more each day like spadefulls of earth slowly burying a coffin, what better time to think ahead to the horrors of Christmas? Not the pedestrian horrors of shopping and family, but the deeper terrors of knifemen and ghosts and dark-souled elves: the traditions of the season. Publisher Spectacular Optical’s planning a celebrate of exactly those kinds of Christmas frights, with their upcoming volume Yuletide Terror: Christmas Horror on Film and Television. Tuesday, July 18, I set off for Fantasia with another full day before me. I planned to watch three films for which I had three different expectations. First was Animals (Tiere), a German film promising surrealism and artfulness. Then the Chinese big-budget special-effects blockbuster Wu Kong. Finally, and perhaps most intriguingly, House of the Disappeared (Si-gan-wi-ui-jip), a Korean horror movie based on a Venezuelan movie called The House at the End of Time (La casa del fin de los tiempos) which I’d seen three years ago during my first year covering Fantasia; I couldn’t help but wonder how that film would translate across cultures.

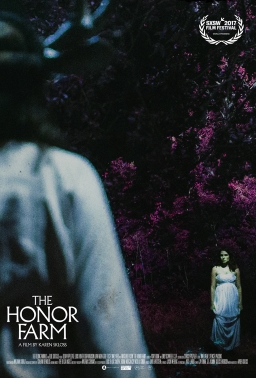

Tuesday, July 18, I set off for Fantasia with another full day before me. I planned to watch three films for which I had three different expectations. First was Animals (Tiere), a German film promising surrealism and artfulness. Then the Chinese big-budget special-effects blockbuster Wu Kong. Finally, and perhaps most intriguingly, House of the Disappeared (Si-gan-wi-ui-jip), a Korean horror movie based on a Venezuelan movie called The House at the End of Time (La casa del fin de los tiempos) which I’d seen three years ago during my first year covering Fantasia; I couldn’t help but wonder how that film would translate across cultures. Sunday, July 16, felt in some ways like the day Fantasia 2017 really began for me. I had three movies I planned to watch, of three very different kinds, though all at the De Sève Theatre. The first was a horror-inflected American independent film called The Honor Farm. The second was a Hong Kong action movie called Shock Wave (Chaak Daan Juen Ga). The third was a Chinese art movie called Free and Easy (Qīng sōng yú kuài). That mix of approaches, genres, and countries was characteristic of the festival. I looked forward to each movie individually, and to how they’d work together.

Sunday, July 16, felt in some ways like the day Fantasia 2017 really began for me. I had three movies I planned to watch, of three very different kinds, though all at the De Sève Theatre. The first was a horror-inflected American independent film called The Honor Farm. The second was a Hong Kong action movie called Shock Wave (Chaak Daan Juen Ga). The third was a Chinese art movie called Free and Easy (Qīng sōng yú kuài). That mix of approaches, genres, and countries was characteristic of the festival. I looked forward to each movie individually, and to how they’d work together. I had an odd schedule on Sunday, July 17. There were two movies I wanted to see. The first was a Chinese historical martial-arts film called The Final Master (Shi Fu), which played at noon. The second was a live-action Japanese manga adaptation, Tokyo Ghoul (Tôkyô gûru), and that played at 9:35 in the evening. I eventually decided to go to the Hall Theatre for the first movie, spend the afternoon doing errands, and return for the second movie in the evening. In the end, this turned out to be a good plan.

I had an odd schedule on Sunday, July 17. There were two movies I wanted to see. The first was a Chinese historical martial-arts film called The Final Master (Shi Fu), which played at noon. The second was a live-action Japanese manga adaptation, Tokyo Ghoul (Tôkyô gûru), and that played at 9:35 in the evening. I eventually decided to go to the Hall Theatre for the first movie, spend the afternoon doing errands, and return for the second movie in the evening. In the end, this turned out to be a good plan. After seeing two showcases of short films on the afternoon of Saturday, July 15, in the evening I went to my first movie of the 2017 Fantasia festival to screen in the 400-seat D.B. Clarke Theatre. That was a film called Mohawk. Directed by Ted Geoghegan, his second film after 2015’s We Are Still Here, with a script by Geoghegan and

After seeing two showcases of short films on the afternoon of Saturday, July 15, in the evening I went to my first movie of the 2017 Fantasia festival to screen in the 400-seat D.B. Clarke Theatre. That was a film called Mohawk. Directed by Ted Geoghegan, his second film after 2015’s We Are Still Here, with a script by Geoghegan and  Saturday, July 15, looked like an unusual day for me at Fantasia: I’d mostly be seeing short films. It’d begin a bit after noon, with a set of shorts called SpectrumFest: Films from the Autism Spectrum, a collection of pieces from young filmmakers on the autism spectrum. Then would come this year’s edition of the International Science-Fiction Short Film Showcase, featuring eight science-fictional short films from around the world. Both showings looked fascinating, if in different ways. SpectrumFest was new to me, but I’d seen the SF showcases in previous years, and been impressed both by the individual films and by the way they worked together — if short films are loosely equivalent to prose short stories, the SF short film showcases make excellent anthologies.

Saturday, July 15, looked like an unusual day for me at Fantasia: I’d mostly be seeing short films. It’d begin a bit after noon, with a set of shorts called SpectrumFest: Films from the Autism Spectrum, a collection of pieces from young filmmakers on the autism spectrum. Then would come this year’s edition of the International Science-Fiction Short Film Showcase, featuring eight science-fictional short films from around the world. Both showings looked fascinating, if in different ways. SpectrumFest was new to me, but I’d seen the SF showcases in previous years, and been impressed both by the individual films and by the way they worked together — if short films are loosely equivalent to prose short stories, the SF short film showcases make excellent anthologies. Friday, July 14, felt like my first real day at the 2017 Fantasia Festival. After only one film the night before, I had three movies I wanted to see that afternoon and evening. First would come Tilt at the 175-seat J.A de Sève Theatre, a thriller that was drawing attention on the festival circuit for its political subtext. After that, at the 700-seat Hall, would come A Ghost Story, a movie about loss; I thought it looked slightly more interesting than the comedic manga adaptation Teiichi: Battle of the Supreme High because A Ghost Story depicted its ghost in the form of an actor with a sheet over his head. The sheer brazenness was appealing. Besides, after that my last film of the day would be another manga adaptation at the Hall, Museum (Myûjiamu), directed by Keishi Otomo. I’d seen and enjoyed two other adaptations by Otomo before, the third Rurouni Kenshin film two years before and then last year The Top Secret: Murder in Mind. The odds seemed good for Museum, a crime thriller about a cop tracking down a frog-masked serial killer.

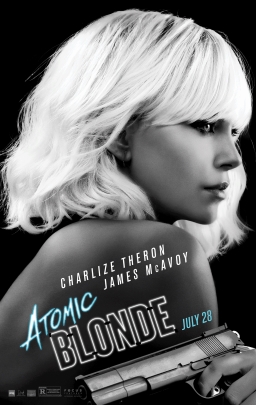

Friday, July 14, felt like my first real day at the 2017 Fantasia Festival. After only one film the night before, I had three movies I wanted to see that afternoon and evening. First would come Tilt at the 175-seat J.A de Sève Theatre, a thriller that was drawing attention on the festival circuit for its political subtext. After that, at the 700-seat Hall, would come A Ghost Story, a movie about loss; I thought it looked slightly more interesting than the comedic manga adaptation Teiichi: Battle of the Supreme High because A Ghost Story depicted its ghost in the form of an actor with a sheet over his head. The sheer brazenness was appealing. Besides, after that my last film of the day would be another manga adaptation at the Hall, Museum (Myûjiamu), directed by Keishi Otomo. I’d seen and enjoyed two other adaptations by Otomo before, the third Rurouni Kenshin film two years before and then last year The Top Secret: Murder in Mind. The odds seemed good for Museum, a crime thriller about a cop tracking down a frog-masked serial killer. I’ve been swamped by movies since the 2017 Fantasia International Film Festival began, and that’s left me with no time to write about the things I’ve seen. It looks like those reviews will start coming next week, after the festival ends. But on Wednesday I saw a movie that’s getting a wide release this weekend, and on the off chance what I have to say might be useful to anybody trying to plan their weekend, I thought I’d abandon my usual diary format to say a few words about Atomic Blonde.

I’ve been swamped by movies since the 2017 Fantasia International Film Festival began, and that’s left me with no time to write about the things I’ve seen. It looks like those reviews will start coming next week, after the festival ends. But on Wednesday I saw a movie that’s getting a wide release this weekend, and on the off chance what I have to say might be useful to anybody trying to plan their weekend, I thought I’d abandon my usual diary format to say a few words about Atomic Blonde.