Fantasia 2017, Days 7 to 9: The Laplace’s Demon

After two days off, I returned to Fantasia on June 21 fit, trim, and rested. Randomness defines my festival schedule — it happened that the previous two days had nothing I wanted to see. But that Friday afternoon I was looking forward to one of the most intriguing movies listed in Fantasia’s catalogue: The Laplace’s Demon, directed by Giordano Giulivi.

After two days off, I returned to Fantasia on June 21 fit, trim, and rested. Randomness defines my festival schedule — it happened that the previous two days had nothing I wanted to see. But that Friday afternoon I was looking forward to one of the most intriguing movies listed in Fantasia’s catalogue: The Laplace’s Demon, directed by Giordano Giulivi.

A team of scientists has worked out how to calculate the complexities of glass shattering. Their mathematics imply a deterministic universe, if the code can be more fully cracked. The movie begins with them on their way to a mysterious island, summoned to the mansion of a reclusive genius. There, in his empty mansion, they find the terrible truth — their host, speaking to them by videotape, is playing a terrible game. He’s gone further than them, pushed the math beyond human sanity. Now the researchers are elements in a vaster experiment: the horrific mechanisms in the isolated house will eliminate them, one by one, if the equations are correct. Can they find a flaw in the math and save themselves? Is there room in the universe for free will?

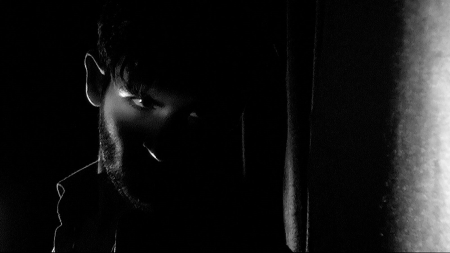

Watching the film play out I saw science-fiction and mystery and horror blend in a classic plot framework. The movie feels like an artifact from Hollywood’s Golden Age, some previously-unknown Val Lewton piece, a forgotten film by James Whale. It’s shot in a heavily-shadowed black and white, much of it in one elaborately-furnished room filled with dark corners and rich art-nouveau details. Close-ups and odd foreshortening adds to an air of unreality, fostered by an unusually tasteful use of CGI. The characters here are caught in a metafictional plot, which can be predicted but not evaded. Clever, well-crafted, it evokes Halloween frissons of delicate horror, surprising while generating a sense of inevitability, moving to a creaky but effective plot climax that resolves its themes with the bleakness of a death’s-head inevitable grin at a deterministic universe.

The Laplace’s Demon was created by a small group wearing many hats. The four producers were director Giordano Giulivi, his brother Duccio Giulivi, Ferdinando D’Urbano, and Silvano Bertolin. The same four men were together responsible for the script (the Giulivis both have “writer” and “story” credit at the IMDB, while the other two are credited with “story” alone). D’Urbano was the film’s cinematographer, played one of the scientists, and edited the movie with Giordano Giulivi — who was also responsible for production design, art direction, and special effects. Duccio Giulivi, meanwhile, played one of the main roles, and handled the music for the film. Bertolin starred and was production coordinator. Look over the IMDB crew list, and you see these names (along with Tamara Boggiano) recur again and again. This wasn’t a large production, in other words; but it feels larger than it was, with scope born from good planning and careful use of visual effects.

Set in modern times — we see a laptop running wirework simulations of the scientist’s breaking glass — there’s an old-fashioned sense to the film. Cell phones don’t work here, as in so many contemporary horror movies, but there’s logic to that: the malevolent Professor Cornelius has built his home on an island. So we watch the black-and-white images and listen to the symphonic soundtrack, and recall the plot mechanisms of times past. D’Urbano’s cinematography fits the proceedings to perfection, wielding shadows and contrast expertly. The lighting’s obviously dramatic, unreal, and yet perfect for a story set in a mansion designed like a set out of the 1940s; as though Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce might wander in at any moment and set things right.

Set in modern times — we see a laptop running wirework simulations of the scientist’s breaking glass — there’s an old-fashioned sense to the film. Cell phones don’t work here, as in so many contemporary horror movies, but there’s logic to that: the malevolent Professor Cornelius has built his home on an island. So we watch the black-and-white images and listen to the symphonic soundtrack, and recall the plot mechanisms of times past. D’Urbano’s cinematography fits the proceedings to perfection, wielding shadows and contrast expertly. The lighting’s obviously dramatic, unreal, and yet perfect for a story set in a mansion designed like a set out of the 1940s; as though Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce might wander in at any moment and set things right.

Neither they nor anyone else does. The story’s straight, a plot-driven horror story that finds its twists in the inherent logic of its premise. Characters are developed enough to be credible and to establish their various roles in the story: this one the dreamer, this one the man of action, this one the analytic scientist. One notes that the old-fashioned sense extends to the inclusion of only one woman in the eight-strong group bound up in Cornelius’ plans.

It also extends to the technology in the movie. The characters watch Cornelius deliver his message on videotape. They listen to music on a gramophone. A grandfather clock ticks away moments: symbolically important, a clockwork mechanism providing a central image for the struggle with determinism. Even more central is a huge model of the house, in which the characters are represented by a group of pawns, which move as a complex network of gears and pistons drive them in perfect synchronicity with the actual movements of the characters through the house. At intervals, a mysterious black queen emerges; the house shakes; and a pawn isolated on its own is taken, as the other characters and we in the audience watch the model. When we finally see what the queen represents the image is perfect; but the point is that everything the characters might do to escape it has been worked out mathematically in advance. Can they find a way to defeat it, against all reason?

It also extends to the technology in the movie. The characters watch Cornelius deliver his message on videotape. They listen to music on a gramophone. A grandfather clock ticks away moments: symbolically important, a clockwork mechanism providing a central image for the struggle with determinism. Even more central is a huge model of the house, in which the characters are represented by a group of pawns, which move as a complex network of gears and pistons drive them in perfect synchronicity with the actual movements of the characters through the house. At intervals, a mysterious black queen emerges; the house shakes; and a pawn isolated on its own is taken, as the other characters and we in the audience watch the model. When we finally see what the queen represents the image is perfect; but the point is that everything the characters might do to escape it has been worked out mathematically in advance. Can they find a way to defeat it, against all reason?

There’s no gore in the film, no violence to speak of. Its suspense comes from a mastery of classical technique. Yet CGI provides backgrounds, and is used to make the machine model of the house. That adds to the artificiality of the film, perhaps, but also enforces the ineluctable quality of mathematics. Computers have worked out the nature of the house and of the model in which the characters are trapped; how can you fight science?

That’s the central question of the film. The ‘Laplace’ of the title is (whatever its relevance to a largely one-location movie) a reference to Pierre-Simon, marquis de Laplace, an 18th-century scientist who was a strong proponent of mathematical determinism: the idea that if you knew the starting point and driving force of everything in the cosmos, it would be possible to predict mathematically every motion that followed through to the end of time. Human history would be only one branch of this ur-mathematics, all our beliefs and dreams and fictions only a byproduct of inevitability and the laws of physics. The mind which Laplace imagined, capable of grasping the entirely of the universe and calculating forward, has become known as “Laplace’s demon.”

That’s the central question of the film. The ‘Laplace’ of the title is (whatever its relevance to a largely one-location movie) a reference to Pierre-Simon, marquis de Laplace, an 18th-century scientist who was a strong proponent of mathematical determinism: the idea that if you knew the starting point and driving force of everything in the cosmos, it would be possible to predict mathematically every motion that followed through to the end of time. Human history would be only one branch of this ur-mathematics, all our beliefs and dreams and fictions only a byproduct of inevitability and the laws of physics. The mind which Laplace imagined, capable of grasping the entirely of the universe and calculating forward, has become known as “Laplace’s demon.”

This a movie, then, in which the monster is math. Practically, though, there are no equations or calculations. The math’s a plot point, not important in itself but a way to tell a story about freedom and tragedy. Can the characters find a way to freedom? Can they do something truly unpredictable? As characters in a tightly-machined script, it seems impossible. The tragic is born out of the inevitable. And yet the idea of such an all-encompassing mathematics is so counter-intuitive the attempt to find a way around it is just as inevitable; which, I suppose, is what makes for any tragedy, a futile attempt to escape the inevitable.

Only, if classical tragedies have shown characters dying for offending God or the gods, this is tragedy’s Deist. Cornelius, the Prime Mover, set things in motion and then absented himself from the scene (presumably). Everything that follows, follows from that. Characters brought face-to-face with this reality, which claims to be a kind of model of the larger mathematical reality of the universe, don’t believe it. Yet the model house is perfectly in tune with the real actions that take place in the house. And, symbolism aside, there’s a monster afoot that makes breaking the equations an immediate task.

Only, if classical tragedies have shown characters dying for offending God or the gods, this is tragedy’s Deist. Cornelius, the Prime Mover, set things in motion and then absented himself from the scene (presumably). Everything that follows, follows from that. Characters brought face-to-face with this reality, which claims to be a kind of model of the larger mathematical reality of the universe, don’t believe it. Yet the model house is perfectly in tune with the real actions that take place in the house. And, symbolism aside, there’s a monster afoot that makes breaking the equations an immediate task.

It seems right that the scientists first drew Cornelius’ attention by modelling the way a drinking-glass shattered. A glass knocked off the table is a recurrent image in the film, as is the image of a glass sitting on a table, awaiting its potential fall like an angel awaiting its inevitable plunge into demonhood. We see the accidental drop and breakage several times. The point, I think, is that the falling glass is an accident, a thing unpredicted by the human intelligence that precipitates the fall. In this movie a greater intelligence can predict its destruction. Accident disappears. The cold equations of destiny are all.

And yet one of the characters, Duccio Giulivi’s Jim Bob, daydreams of flying. Of escaping the gravity that pulls at the glass. Never mind whether the daydream can be made real; or, if it could, whether it would simply recapitulate the tale of Icarus. I wonder whether the point is the daydream itself. In the big picture, Laplace’s mathematical demon must be able to predict daydreams and fiction; they’re a part of destiny. But predicted or not, the dream and the art have meaning. What happens to the dreamer? What happens, in the end, to the intelligence capable of predicting all the universe? Can the intelligence predict itself, and if so, can it really escape its own predictions?

And yet one of the characters, Duccio Giulivi’s Jim Bob, daydreams of flying. Of escaping the gravity that pulls at the glass. Never mind whether the daydream can be made real; or, if it could, whether it would simply recapitulate the tale of Icarus. I wonder whether the point is the daydream itself. In the big picture, Laplace’s mathematical demon must be able to predict daydreams and fiction; they’re a part of destiny. But predicted or not, the dream and the art have meaning. What happens to the dreamer? What happens, in the end, to the intelligence capable of predicting all the universe? Can the intelligence predict itself, and if so, can it really escape its own predictions?

These things may appear abstract. The film works because it makes them vital. It’s a well-told suspense story about a group of characters trapped on an island being whittled down one by one. And it’s a philosophical drama about free will. Both aspects succeed. It’s one of the strongest pieces I saw at Fantasia this year.

After the film there was a question-and-answer session with the Giulivis, D’Urbano, and Bertolin. Per my handwritten notes, Giordano Giulivi took most of the questions, starting with the first regarding the gestation of the project. He said the script came first, but that they spent a lot of time thinking about the idea. He said it took roughly two years to develop the idea and polish the screenplay to bring out all the paradoxical elements in it. Asked if the ending was always in place, he said it was a “Good question. Very good.” In fact they did not have the ending at first, but worked their way through the script chronologically until they found the ending that tied everything together — as he said, Laplace found the ending for them.

Asked how much of the film used miniatures as opposed to CGI, Giulivi said everything was CGI, which he personally created; the process took a lot of time. Asked whether there were any notable Italian film influences in the movie, as opposed to the obvious American influences, he said no. He was then asked why a script seen briefly in the film was in English, and he said they shot three versions of the scene, exactly the same except for the language of the script (Italian, English, and French). I was then surprised to hear him deny that the idea of the formula was meant as a metaphor for cinema.

Asked how much of the film used miniatures as opposed to CGI, Giulivi said everything was CGI, which he personally created; the process took a lot of time. Asked whether there were any notable Italian film influences in the movie, as opposed to the obvious American influences, he said no. He was then asked why a script seen briefly in the film was in English, and he said they shot three versions of the scene, exactly the same except for the language of the script (Italian, English, and French). I was then surprised to hear him deny that the idea of the formula was meant as a metaphor for cinema.

Asked if the movie was filmed in sequence, Duccio Giulivi said yes, it was shot chronologically, and that it was difficult for him to get into character at the beginning; but everything came together. Bertolin observed that the ending was most difficult for him as an actor. The shoot itself, according to the director, was four years — long enough that it was difficult to keep the actors looking consistent. Duccio Giluivi, spear-bald in the movie, observed he personally needed a lot of help from the hairdresser. D’Urbano was asked how he kept the look of the film consistent over that length of time, and he said it was actually fun, and that it was more difficult to light the actors and then light himself using the director as a stand-in for his character.

Asked how it felt to finally show the movie after a 7-year production process, Giordano Giulivi said simply “Like a dream.” Asked why Duccio’s Giulivi had the not-terribly-Italian-sounding name Jim Bob, the actor said it was a long story, and that the character was carried over from their previous film; it was a name they like a lot. Asked about the image of the mechanism that the black queen represented, the director said it symbolised the conflict of life and death, and the inevitable triumph of the latter. It was, he said, an explicit way to represent death.

Asked how it felt to finally show the movie after a 7-year production process, Giordano Giulivi said simply “Like a dream.” Asked why Duccio’s Giulivi had the not-terribly-Italian-sounding name Jim Bob, the actor said it was a long story, and that the character was carried over from their previous film; it was a name they like a lot. Asked about the image of the mechanism that the black queen represented, the director said it symbolised the conflict of life and death, and the inevitable triumph of the latter. It was, he said, an explicit way to represent death.

That ended the questions and answers, and I set off for home. It had been a short day, but a rewarding one. Next came the weekend, always busy at Fantasia; not being an intelligence of the quality of Laplace’s demon, I could not predict what I’d end up seeing. Unspoiled by precognitive math, I had in fact just shy of two weeks of films left to me, the festival now well underway. How to predict not just one world, but the many different universes of so many different movies?

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.