A Fascinating, Ordinary 1950s SF Novel: Robert Silverberg’s Collision Course

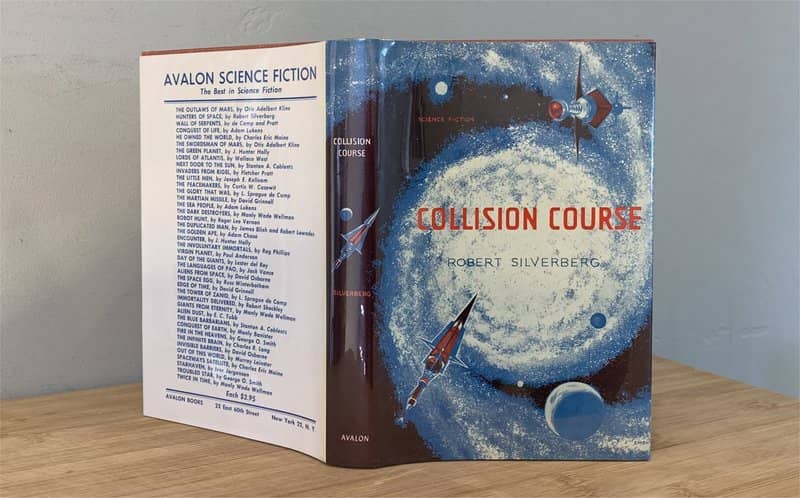

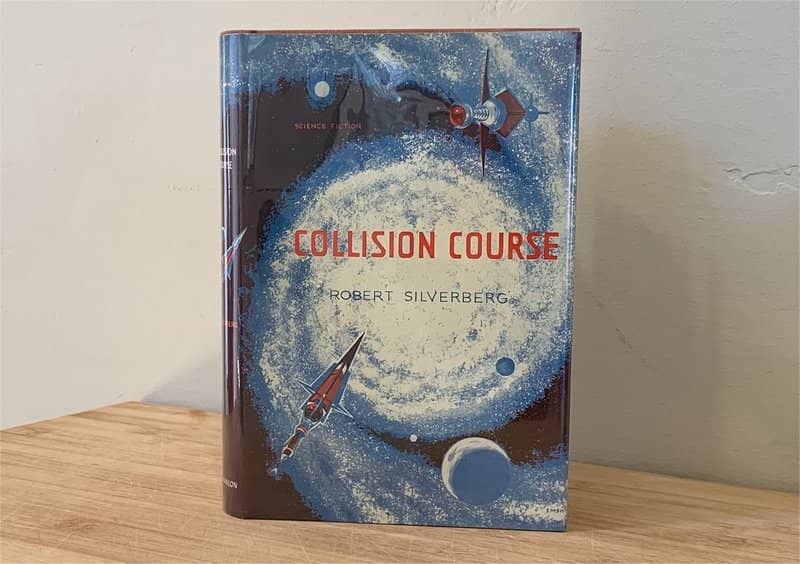

Collision Course by Robert Silverberg. First Edition: Avalon Books, 1961.

Jacket design by Ed Emshwiller (click to enlarge)

Collision Course

by Robert Silverberg

Avalon Books (224 pages, $2.95 in hardcover, 1961)

Robert Silverberg needs no introduction to readers of Black Gate, I should think — author, over six or seven decades, of dozens of novels and hundreds of short stories, editor of rows of reprint and original anthologies, winner of four Hugo Awards, five Nebula Awards, and numerous career awards including induction into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame, an SFWA Grand Master, and the First Fandom Hall of Fame — yet it’s easy to come across unfamiliar titles from along the twists and turns of his long and varied career. He began in the 1950s, a prolific author of short stories and of standard genre SF novels that he was able to write and sell quickly, and while some of them have been reprinted several times in decades since, this early body of work has been eclipse by the high quality work of the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, for which he won many of those awards, and by later popular works such as his Majipoor novels and stories.

The novel at hand is one of those earlier works, and it’s interesting precisely because it’s not a major work of science fiction in any way.

Rather, it’s utterly typical of science fiction of its era in its presumptions and assumptions about the ways of the universe and the possibilities of human contact with alien races — ideas that have become clichés that have permanently settled into modern popular culture’s conception of science fiction, especially in Star Trek and Star Wars and all their permutations over the decades. That is, those franchises have frozen into popular culture the ideas of primitive science fiction of the 1940s and ‘50s (Trek) or 1930s and ‘40s (Wars) that literary science fiction, at least at its more ambitious, have surpassed and left behind. No one would write a novel with such a simplistic theme as this one’s today.

And why this average 1950s era SF novel and not some other? Mere serendipity. In early 2019 I attended an Antiquarian Book Fair that’s held annually in downtown Oakland. (This year’s fair was held in February.) I’ve been in dozens of SF convention dealers’ rooms over the decades, but never to an equivalent public event not restricted to genre books. It was indeed like a very high-end convention dealer’s room, a large corner of the downtown Oakland Marriott, divided into rows of booths with dealers from around the world. The two or three dealers specializing in science fiction were the equivalent of the best book dealers at the largest science fiction conventions, in terms of their range, quality, and price, while the balance of the fair consisted of dealers specializing in other genres or general books and selling rare items to the tune of several thousands, or tens of thousands, of dollars. Several books caught my eye, nothing essential, but determined to buy something, I found this Silverberg volume (which I had an earlier Ace edition of already), a fine crisp first edition, for only… $50. About the least you could pay to buy any book at the event. A few days later, I read the book in about 3 hours, and I’m not a fast reader.

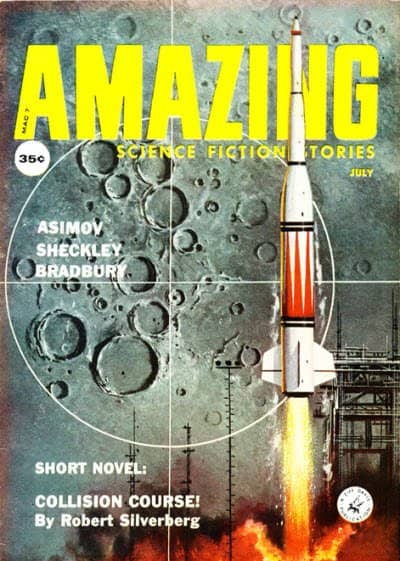

“Collision Course” by Robert Silverberg, in Amazing Science Fiction Stories,

July 1959, edited by Cele Goldmsith. Cover art by Albert Nuetzell

The story was first published as a “short novel” in Amazing Science Fiction Stories for July 1959, and was published (without expansion) in 1961, first in hardcover for Avalon and later in the year as half of an Ace Double.

Summary

- Humans in 2780 have colonized hundreds of planets and, finally having an FTL drive, discover their first aliens.

- It’s the year 2780, and humans have colonized all the planets within 400 light years, via slower-than-light ships that place “transmat” devices on each planet to enable instantaneous teleportation to and from Earth. No aliens have been discovered.

- The world is run by a set 13 Archons, out of whom the Technarch is McKenzie.

- The story opens as the first FTL ship returns from its first experimental run. The ship has discovered a planet some 9800 light years away, where an alien race (from some other planet) is building a colony. The Earth ship departed without being detected by the aliens.

- The Archonate debates. This discovery is a great threat to humanity, because it means two races both colonizing planets will meet in a collision course. McKenzie decides to send the FTL ship back, with the same crew and some negotiators, to establish an “entente.”

- In London Dr. Martin Bernard, a twice-divorced sociologist, is enjoying his poetry and brandy when the phone rings — it’s the Technarch, asking for his participation on this trip. Bernard agrees, and quickly packs and transmats to New York. There he meets the others: Havig, a Neopuritan with whom Bernard once had a seething exchange about a paper of Havig’s; Stone, a politician; and Dominici, a biophysicist.

- The ships sets off, takes a day or two to reach Pluto before it can use the FTL; they pass through a space with no stars; they exit near the target planet and land 10 miles from the alien colony.

- Humans confront the aliens and try to negotiate a truce to divide the galaxy for colonization between them.

- They hike to the alien colony and observe humanoid aliens, green workers supervised by blues. They approach, are seen, and through gestures announce their friendliness, and shake hands. The aliens have big eyes and two elbows on each arm.

- The aliens, Norglans, quickly learn Terran, and after 9 days begin to negotiate with the humans, about setting a boundary of some kind for each race’s settlements. But the local alien leaders claim they don’t have such authority.

- Two other aliens arrive, tall blue-purple ambassadors. (Apparently the aliens have some kind of transmats too.) The humans create a diagram of the galaxy and their areas, with rays indicating how each race should extend. The ambassadors respond by wiping the rays out — and state that humans will be allowed to keep the planets they’ve already colonized, but all others belong to the Norglans. The two ambassadors withdraw.

- The humans are aghast; is this a bluff; are the aliens asking for war? Should they try again? They do try again, but the ambassadors are gone and will not return.

- The humans head back to Earth. Bernard reads poetry — Shakespeare, in the original English. The ship comes out of FTL and — is lost! The FTL drive is still experimental, after all.

- They’re deduce that they’re in the Greater Magellanic Cloud, see the Milky Way, and take in the perspective. It’s impossible to return the same way, given the random element of the FTL drive; they may need to find a local planet and settle down. Havig, who has been calm and aloof so far, breaks down into sobs, thinking this must be punishment for some sin. Bernard reminds him of Job.

- A third superior alien race intervenes and implements a compromise.

- And then the ship is seized by some external force and dragged to a nearby star, at great speed. A figure appears inside the ship, hovering in the air, a creature calling itself a Rosgollan. Its race has watched the humans and their ship, and been amused.

- The ship is set down on a pastoral planet, where the human crew are spirited away to a room in which several Rosgollans “interrogate” them by drawing knowledge of their pasts directly from their minds – and then laugh. The humans exit into a valley, their ship nowhere to be seen, and find food left for them.

- In the morning the two Norglan ambassadors appear! A crowd of Rosgollans surrounds all of them, and says they are here to settle the dispute. (Humans and the Norglans are the only intelligent species in the Milky Way, it seems, but the Rosgollans are far superior.) Bernard is compelled to speak in defense of Earth. The Rosgollans perceive that both races have the presumption to think themselves worthy of settling all of space.

- A model of the galaxy is shown; a boundary down the middle is shown. The two sides have no choice — this is an order. Any incursion from one side to the other will be met with corrective actions. And now, they will be returned to their planets. Back in their ship, the humans debate whether this is a huge defeat, or what, and they consider some evolutionary perspective. Stone is upset, fearing he’ll lose his job. But Bernard finds reason to be optimistic.

- Humans accept their fate, and their place in the universe.

- After they’ve returned to Earth, Bernard meets McKenzie and gives him the full story. McKenzie is broken, his dreams of colonizing the “universe” in his lifetime frustrated. Bernard tries to make him see the big picture: he still has half the galaxy, and now they know their true place in the universe.

Collision Course by Robert Silverberg. First Edition: Avalon Books, 1961.

Jacket design by Ed Emshwiller (click to enlarge)

Notes

This reads like a mashup of several Trek episodes, with a bit of 2001 thrown in. (Because, of course Star Trek derived its premises from 1950s sf, and in 2001 Clarke used familiar ideas from his own earlier 1950s works.)

- We have the standard SF furniture of telepads and FTL drives. We have human colony worlds and the absence of aliens, and the unquestioned assumption that humanity has a manifest destiny to spread out and conquer the entire universe!!

- We have humanoid aliens who, conveniently, learn the human language fairly quickly so that the plot can proceed, and whose expansionist motives are the same as humans’. (In Trek communication was even easier; the problem was ignored.)

- We have superior aliens who step in to take charge, just as aliens did in Clarke’s Childhood’s End and in 2001, and in Trek episodes like “Errand of Mercy” and “Arena.”

- We have the superior aliens take over the human ship move it across space at great speed. Page 152:

In the vision screen, the stars rushed blindingly toward them, their disks streaking and changing color, and sped past. …[T]hey were heading toward a yellowish sun that grew by gigantic bounds with each passing instant…

This kind of transit through hyperspace, or movement through space at impossible speeds, was familiar in classic science fiction. When 2001 came around seasoned SF readers had no trouble realizing what they were seeing, however fancifully it was visualized. Naive viewers were confused, or thought it a drug trip. (Of course Clarke spelled it out in his novel version of the film.)

- And we have the belated recognition that humans aren’t the most superior species in the universe. (As I read the book, I thought, Astounding editor John W. Campbell presumably would not have bought this story, on that point alone. But while compiling this review I read Silverberg’s introduction to the 1977 Ace edition, pictured below. He in fact intended it for Campbell, toning down “melodrama and swordplay” for “an adult story about adults” but indeed Campbell rejected it on precisely predictable grounds:

For John, a story about Earthmen who have doubts, who admit the possibility that grabbing half the galaxy on behalf of imperialist Earth might not be a good idea, and who ultimately run into superior opponents, was not a story that he was going to publish, because it advocated points of view that were just downright wrong.

And so Silverberg sold it to Paul Fairman at Amazing.)

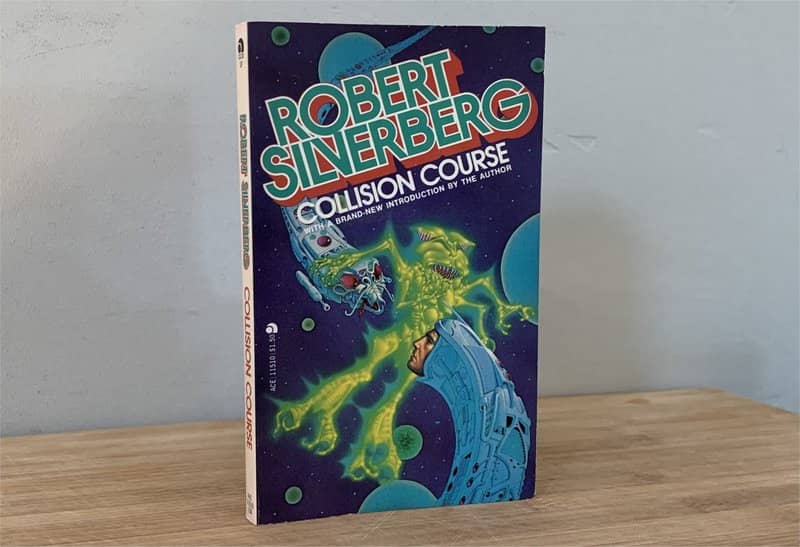

Collision Course by Robert Silverberg. Ace Books, February 1977.

Cover art by Don Punchantz (click to enlarge)

At the same time, the book is simplistic, even dimwitted, on a couple points. (This is not to impugn the author, so much as the assumptions of 1950s SF.)

- Why at the end is the Technarch so broken to realize he has only half a galaxy and the not the entire universe? No one seems to appreciate the scale of the difference. He seems to think that the entire universe would be settled within his lifetime, under his supervision.

- Almost as simplistic and naïve is the assumption that the first alien race found by humanity is the only one out there in the entire universe. Granted the failure to encounter an alien race within 400 light years is significant, but how is finding just one within 10,000 light years – within a galaxy some 200,000 light years across – mean that these two races can negotiate the entire universe? At least the humans recognize their presumption:

And to think that we and the Norglans were all set to divvy up the universe between us! What cosmic arrogance, what supreme gall! What right do any of us, in our puny little galaxy, have to stake even a tentative claim out there?

- On the other hand, here on Earth just a few hundred years ago Spain and Portugal presumed to divide up the New World between them (Wikipedia: Treaty of Tordesillas), so maybe this reaction isn’t so implausible after all.

- Minor point: as in most SF of the time, and as Trek did, it’s very casual about mentioning actual star names – here, Betelgeuse and Bellatrix – without caring how far away they actually are from each other. (The former is 700 light years away, the latter only 250 light years away, though of course at least they’re in more-or-less the same direction from Earth.) And in the description of their passage through space quoted above, they perceive they’re moving at virtually the speed of light. But even at the speed of light, stars would not visibly stream past; that’s also a basic Trek error.

Other comments

- The Neopuritan character is interesting, appearing as a foil, presumably, but also representative of how SF typically regarded (regards?) persons of faith and traditional morals. Havig is prim and presumptuous – he has a breakdown when he thinks their ship is marooned because of some sin of his — and others tell him to shut his trap.

- The Archonate scheme is described in chapter 10, and it’s mentioned page 54 that each archonate is trained for decades to assume his position. Future meritocracies were more frequently imagined in classic SF than they are now, I think; Trek’s “Space Seed” showed how the scheme might go awry.

- There are philosophical passages about the lack of choice in the universe, pages 61 and 82, and about the humanoid form of the aliens, perhaps to echo how similar in motivation the humans and aliens are. (Silverberg is using italics to indicate interior thoughts.)

There’s hardly any choice. We’re prisoners of — well, call it necessity for lack of a neater term. The only choices we get are low-level ones; and maybe we aren’t even really choosing them.

So they differed from Earthmen in pigmentation and in most of the minor details — but the overall design was roughly the same, as if only one pattern could serve for intelligent life.

Again a lack of choice, Bernard thought with a philosophical detachment that surprised him as his trembling legs continued to move him forward. The universe gives us the impression of free will, but in the really big things there’s only one possible way that things can be.

- This is tempered by some perspective on how long, or short, it’s taken humans to go from primitive to transmats in half a million years, page 204, reflecting how far ahead of humans the superior aliens are:

And yet we came all the way from Pithecanthropus erectus to the transmat era in half a million years — picking up speed as we came. That’s a hell of a long journey in not really a hell of a long time. So who’s to say where we’ll be half a million years from now? We can predict where we’ll be when we’re as old as the Rosgollans are now?

This recognition that humanity isn’t the center of the universe, or its ultimate achievement — despite John W. Campbell — is the perspective and sense of wonder some of us come to science fiction for.

Mark R. Kelly’s last review for us was of City by Clifford D. Simak. Mark wrote short fiction reviews for Locus Magazine from 1987 to 2001, and is the founder of the Locus Online website, for which he won a Hugo Award in 2002. He established the Science Fiction Awards Database at sfadb.com. He is a retired aerospace software engineer who lived almost his entire life in Southern California, though in 2015 resettled in the Bay Area. Find more of his thoughts at Views from Crestmont Drive.

Mark,

Fascinating review. COLLISION COURSE was the very first Silverberg novel I ever read, and one of the first SF novels period. I read it in 1977, when I was 13. I passed it around to my friends and we discussed it to death (as we did with all SF novels we shared).

I agree with you completely that it’s a very minor novel, and I knew that even at 13. And I think you really nailed the major problems with it — especially the huge naivety around mankind’s hubris. I suspect it would have had a bigger impact on (and was probably aimed at) Campbell’s SF readers who accepted the empire-building themes of 50s and 60s SF without question, but that piece still scored with me, even as a very young SF reader.

Of all of Silverberg’s novels, COLLISION COURSE has lingered in my mind the longest. I used to think it’s because it was the first (and because, naturally enough, we probably remember the novels we shared and enthusiastically discussed in our youth far longer than the ones we read in isolation as adults).

But I think your article has finally helped me understand the real reason — the book was a slap in the face to the part of SF that desperately needed a slap in the face.

I enjoyed this book for the same reason I think the Star Trek episode “Arena” is superior to Fredric Brown’s source material. Kirk’s decision not to kill the Gorn (starkly contrasted with Bob Carson’s decision to kill the alien in Brown’s short story) is a powerfully redemptive moment.

I want to be part of a Federation that lives by that kind of peaceful creed far more than I want to be part of a Campbell-style Terran Empire, and I don’t care how glorious it is.

Anyway, great job. Looking forward to the next one!

Interesting – like you say – how a lot of these ideas were reused in Star Trek. I laughed at the idea of two races carving up the entire universe between them. It reminded me of an old Irish TV sketch that was a riff on the traditional rivalry between Ireland’s two chief cities, Dublin and Cork. The cities have divided the universe between them but the Corkonians are still grumbling that Dublin got all the best bits (the milky way, etc). I guess hindsight is a wonderful thing. I remember coming across a headline in an Irish paper – from the Fifties – in which a senior Irish cleric warned how mankind was losing its moral and spiritual perspective in its quest to conquer space(!).

And funny (again, like you say) how races from very different parts of the galaxy are often so physically similar. I could understand the logic of this when it came to costumes for a TV series (STTNG was just as culpable as the original Star Trek, although it did ultimately come up with some sort of explanation in ‘The Chase’) – but in books?

Last year, I started a project to read all Robert Silverberg’s novels, short story collections, and anthologies in order starting with Revolt on Alpha C. (I’m skipping his erotica and his nonfiction… one has to draw the line somewhere!)

I have made it through 1958’s Invisible Barriers. Next up is Collision Course.