Fantasia 2021, Part LXIX: Dear Hacker

I wrote a little while ago about watching three documentary films bundled together at the 2021 Fantasia Film Festival, centred around the short feature You Can’t Kill Meme. There was another set of three documentaries at Fantasia this year, and as the festival drew to a close, I sat down to watch them as well. These two shorts and the short feature Dear Hacker were a bit more diverse in subject matter, but shared themes of technology and power.

I wrote a little while ago about watching three documentary films bundled together at the 2021 Fantasia Film Festival, centred around the short feature You Can’t Kill Meme. There was another set of three documentaries at Fantasia this year, and as the festival drew to a close, I sat down to watch them as well. These two shorts and the short feature Dear Hacker were a bit more diverse in subject matter, but shared themes of technology and power.

First was writer-director Aleix Pitarch’s “Orders,” a disturbing animated short based on a true story. The movie re-creates a horrific phone call that was made to a fast-food restaurant by a man claiming to be a police officer, using actors and an edited transcript of the call (I am not sure where the transcript is supposed to have come from, but the events are clearly based on a deeply disturbing reality). Without going into detail, the story’s a dark working-out of something like Stanley Milgram’s experiments about authority and what ordinary people can be ordered to do. As we hear bits of the phone call, and hear things getting worse and worse, we see everyday images of the day’s work at a fast-food restaurant.

The film’s effective at creating an emotional reaction, contrasting horrific audio with flat 2D images of banal restaurant chores. And the double meaning of ‘orders’ is clever. But I found it went on too long at 30 minutes. It’s a fine balance — the film needs to run a certain amount of time to establish the build-up of events, but I found it ended up too far in the other direction, dragging on after you see where things are going. The visuals don’t help, being relentlessly ordinary by design. Still, it’s an effective approach to a terrible subject.

The film’s effective at creating an emotional reaction, contrasting horrific audio with flat 2D images of banal restaurant chores. And the double meaning of ‘orders’ is clever. But I found it went on too long at 30 minutes. It’s a fine balance — the film needs to run a certain amount of time to establish the build-up of events, but I found it ended up too far in the other direction, dragging on after you see where things are going. The visuals don’t help, being relentlessly ordinary by design. Still, it’s an effective approach to a terrible subject.

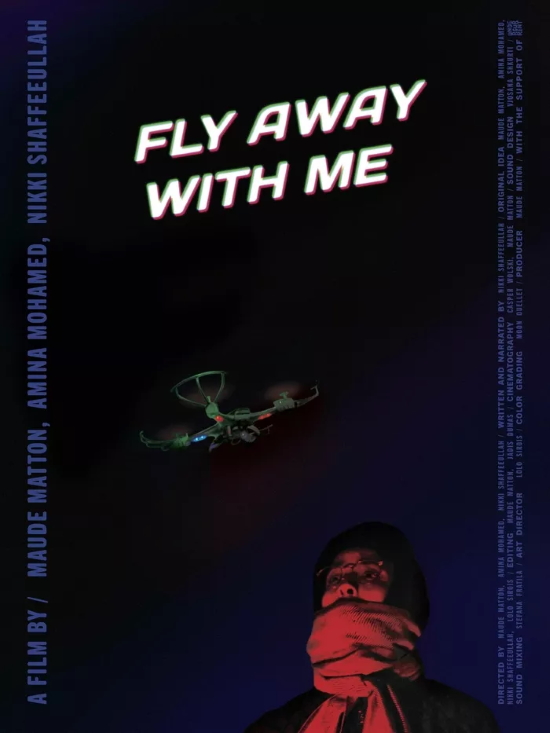

Then came “Fly Away With Me,” by directors Maude Matton, Amina Mohamed, and Nikki Shaffeeullaha (the last of whom is also the writer), a ten-minute piece that tries to imagine a prison drone ‘defecting’ to the side of protestors. It’s told in voice-over from the drone’s perspective, recalling its life and career up to the point of its change of heart. The story doesn’t work, though; there’s no science-fiction justification for a sentient drone, and no logic to why the drone feels the way it does. It’s transparently a way to structure information about drone use in prisons and law enforcement, and although I sympathised with the aims of the filmmakers I found myself annoyed with the conceit; it’s enough like an actual narrative that its patchiness undermines what the movie’s doing. (The excellent editorial cartoonist Tom Tomorrow pulled this sort of thing off much better in his strip This Modern World, with his character Droney.) And I’m not wild about the filmmakers’ choice to use video clips from American prisons to illustrate a story that takes place in Canada — I could be convinced that the two prison systems are similar enough for this to work, but the film doesn’t even try, which feels like a red flag.

Then came “Fly Away With Me,” by directors Maude Matton, Amina Mohamed, and Nikki Shaffeeullaha (the last of whom is also the writer), a ten-minute piece that tries to imagine a prison drone ‘defecting’ to the side of protestors. It’s told in voice-over from the drone’s perspective, recalling its life and career up to the point of its change of heart. The story doesn’t work, though; there’s no science-fiction justification for a sentient drone, and no logic to why the drone feels the way it does. It’s transparently a way to structure information about drone use in prisons and law enforcement, and although I sympathised with the aims of the filmmakers I found myself annoyed with the conceit; it’s enough like an actual narrative that its patchiness undermines what the movie’s doing. (The excellent editorial cartoonist Tom Tomorrow pulled this sort of thing off much better in his strip This Modern World, with his character Droney.) And I’m not wild about the filmmakers’ choice to use video clips from American prisons to illustrate a story that takes place in Canada — I could be convinced that the two prison systems are similar enough for this to work, but the film doesn’t even try, which feels like a red flag.

The centrepiece of these three documentaries was Dear Hacker, an hourlong French film directed by and starring Alice Lenay. Lenay, an artist and filmmaker, recently got her PhD in philosophy, specifically on the subject of communicating by screen. As the film opens, she’s seen the light on her computer indicating camera activity activate when she wasn’t using the camera, and she’s intrigued. And thus the movie, a series of Zoom calls in which she communicates with friends and acquaintances to discuss what’s happening with the computer, the nature of the technology, and the philosophical implications of computers and cameras and the possible interloper in the black box attached to her screen: an entity who may or may not exist, Schrödinger’s hacker.

It’s almost stereotypically French. When something strange happens with the webcam, Lenay calls up tech-proficient associates so they can have philosophical dialogues about representation and reality. In fact it struck me as French on a deeper level: some of the ideas here reminded me of Baudrillard and maybe Derrida (both of whose works I mostly know at second-hand, so take that for what it’s worth), while the cinematic form somewhat recalls late-period Godard with its rigorous grunginess and unconventional attention to form. Most of the film is a series of Zoom calls, with a few other images (notably a sequence of a webcam disintegrating). A Fantasia question-and-answer session established that Lenay deliberately created her ‘self’ shown in the documentary as a fictional character, while the apparent back-and-forth dialogues were assembled in editing; the nature of representation is imbedded in the structure of the documentary.

It’s almost stereotypically French. When something strange happens with the webcam, Lenay calls up tech-proficient associates so they can have philosophical dialogues about representation and reality. In fact it struck me as French on a deeper level: some of the ideas here reminded me of Baudrillard and maybe Derrida (both of whose works I mostly know at second-hand, so take that for what it’s worth), while the cinematic form somewhat recalls late-period Godard with its rigorous grunginess and unconventional attention to form. Most of the film is a series of Zoom calls, with a few other images (notably a sequence of a webcam disintegrating). A Fantasia question-and-answer session established that Lenay deliberately created her ‘self’ shown in the documentary as a fictional character, while the apparent back-and-forth dialogues were assembled in editing; the nature of representation is imbedded in the structure of the documentary.

The conversations don’t follow any obvious dramatic or intellectual structure that I noticed, though they do bring up a number of intriguing ideas. One participant observes “that’s what’s cool about surveillance — there’s someone who cares about us.” There are discussions of the boundary between computers and living things, and whether they can be viewed as creatures whose living conditions are not ours, and whether cameras can be viewed as organs of sight. Elsewhere again, a computer tech describes his experience of affecting systems by his presence — having a tech in a room caused people to calm down so that somehow the malfunction that led to him being called in was no longer present, a purely psychosomatic cure.

There’s some discussion of the hacker as an unseen character in the film, though I found said character tended to fall away as the film went on. Lenay seems more conscious in presenting herself as a character, and in talking about the nature of character as represented on screen and as percieved by others. In that sense, the hacker’s a ghost, literally a ghost in the machine, and Lenay discusses how the possibility she’s being watched causes her not just to change her behaviour in a specific way but to experiment with a range of different behaviours.

There’s some discussion of the hacker as an unseen character in the film, though I found said character tended to fall away as the film went on. Lenay seems more conscious in presenting herself as a character, and in talking about the nature of character as represented on screen and as percieved by others. In that sense, the hacker’s a ghost, literally a ghost in the machine, and Lenay discusses how the possibility she’s being watched causes her not just to change her behaviour in a specific way but to experiment with a range of different behaviours.

On the other hand, there’s also a discussion at one point about the sense of being before a computer as similar to a bodiless state, and then that’s contrasted with the physical nature of the screen. There’s an awareness, generally, of the physical or pictorial qualities of the screen, appropriate given Lenay’s academic specialty. I note also that near the end she talks about the film in some of her Zoom calls, so the film becomes a record of its own compilation. I found it appropriate to watch the movir streaming onto a screen in my home, though Lenay’s said she hoped for a theatrical presentation, which would have given a different dimension to the Zoom artifacts, to the lags and to the sound briefly out of sync with the image.

Does the film work as a coherent whole? It’s interesting, but I found it a series of ideas rather than a logically or intuitively developed series of thoughts. It’s a video essay more than a traditional documentary, the cinematic equivalent of creative nonfiction, with an interesting but limiting visual form. There’s a weirdly cyberpunk undercurrent to the film, exploring the kind of unanticipated personal consequences of new technologies one finds in a William Gibson novel. Still, while the ideas are interesting, I’m not sure they’re interesting enough to hold the attention of viewers without a pre-existing interest in the subject for the movie’s 60-minute runtime. Dear Hacker is interesting, but as a whole perhaps not compelling to viewers who are not philosophers of technology.

Does the film work as a coherent whole? It’s interesting, but I found it a series of ideas rather than a logically or intuitively developed series of thoughts. It’s a video essay more than a traditional documentary, the cinematic equivalent of creative nonfiction, with an interesting but limiting visual form. There’s a weirdly cyberpunk undercurrent to the film, exploring the kind of unanticipated personal consequences of new technologies one finds in a William Gibson novel. Still, while the ideas are interesting, I’m not sure they’re interesting enough to hold the attention of viewers without a pre-existing interest in the subject for the movie’s 60-minute runtime. Dear Hacker is interesting, but as a whole perhaps not compelling to viewers who are not philosophers of technology.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.