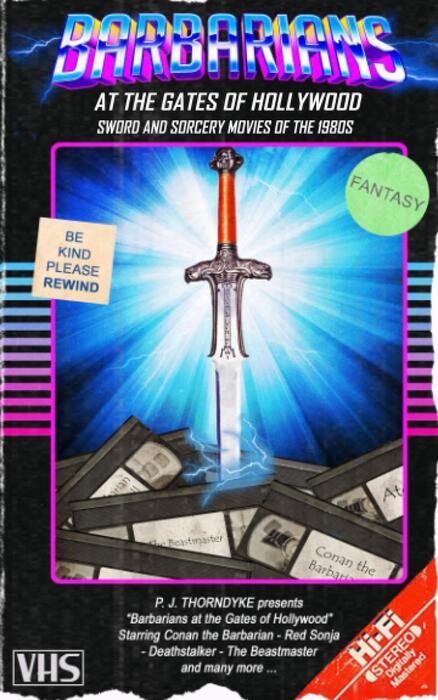

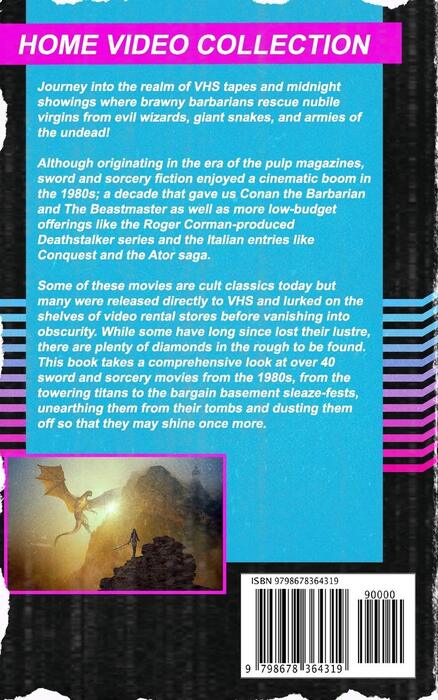

Barbarians at the Gates of Hollywood by P. J. Thorndyke

|

|

Let me start with a story from when I was fifteen and had yet read only the Lancer Conan the Warrior, but was friends with several serious Conan (and Kull, and Solomon Kane) readers. They learned that Creation Con in Manhattan would include a presentation about the upcoming movie Conan the Barbarian featuring Valeria actress Sandahl Bergman, and they quickly convinced a bunch of us to get tickets. On a Saturday afternoon, we made the drive into the city. My memories of the convention itself are pretty hazy, but the movie preview is etched in my brain. Bergman was beautiful and funny. Any teenage boy would want to see the movie after seeing her. The rest of the presentation, though — woohoo, it stank. It was a slide show, just a batch of lifeless stills that, if they didn’t kill our enthusiasm for the movie, they definitely dimmed it. Nonetheless, we all saw it as soon as we could.

All these years later, I can’t speak to how my friends felt, but I hated the movie. I just rewatched it and now, having read all of Howard’s original stories several times, I hate it even more. But that’s a conversation for another day. My opinion, sadly, didn’t matter, and Conan the Barbarian became a cult success, helped make Arnold Schwarzenegger a star, and set the stage for an explosion of barbarian-themed movies. It’s that eruption of films starring loin-clothed, overly-muscled warriors that is the subject of Barbarians at the Gates of Hollywood by P.J. Thorndyke.

When I stepped back from reviewing at Black Gate (almost two years ago — holy shlamoley!) I knew there could always be something to lure me back. Clearly, John O’Neill knew what that something was when he saw it. He e-mailed me a copy of Barbarians at the Gates of Hollywood, I scanned it and immediately knew I had to read it. It opens with a solid history of sword & sorcery and closes with a brief explanation of why the film genre died. The heart of the book are synopses of dozens, if not all, of swords and sorcery movies of the eighties. If you’ve ever had any interest in movies like Thor the Conqueror or how Richard Corman came to produce such fare as Deathstalker II: Duel of the Titans in Argentina, this is the book for you.

Thorndyke breaks the movies out into four chronologically overlapping groups. The first chapter, “The Barbarian Tide,” contains the most important films in terms of influence and of quality. They represent a serious attempt by filmmakers to create successful sword & sorcery movies by approaching them with the same level of technical and artistic seriousness as given to any other genre. The commercial achievement of these movies was enough to spark interest from imitators in the US and Italy who relied on speed and titillation rather than quality to make a profit.

The sword and sorcery movie wave, as presented by Thorndyke, didn’t begin with Conan the Barbarian, but several years earlier with Hawk the Slayer (dir. Terry Marcel, 1980). Featuring a tremendously overacting Jack Palance as the villain, Voltan, it’s not really an S&S movie, but it’s good fun. In addition to the titular hero, there’s a giant, an elf, and a dwarf, making this the most D&D-like fantasy movie around.

The next film described is The Sword and the Sorcerer (dir. by Albert Puyn, 1982). As Thorndyke points out, with characters named King Richard and Cromwell, the atmosphere is more high fantasy than S&S. At the same time, as played by Lee Horsley, Talon, Richard’s son is closer to an S&S protagonist, driven by revenge more than any virtuous desire to restore law and deliver justice. Rated R, there’s also all the blood and gore the effects budget allowed. I haven’t seen this one all the way through, but Thorndyke makes a good case for its watchability. (John Searle, here at Black Gate, makes an even stronger case for its worthiness, despite a significant level of cheesiness and lack of originality.)

It’s with the third entry, the much-loved Conan the Barbarian (dir. John Milius, 1982), that the S&S movie boom truly begins. Hitting the screens two weeks after The Sword and the Sorcerer it was not a blockbuster, but became a massive cult movie and catapulted Arnold Schwarzenegger to superstardom. Despite cribbing bits and pieces from various Robert E. Howard stories, scriptwriters Oliver Stone and Milius created their own tale that tossed aside most of the authentic Howardian storytelling in favor of some silly Nietzschean philosophizing. Nonetheless, the film made an impression. I’ve seen more than one man spend money on a replica of the sword from the movie. It also pointed the way for the great low-budget producer Roger Corman and a host of Italian directors. The great majority of S&S movies were churned out by them in direct response to Milius’ film.

Conan, despite a woefully huge number of shortcomings, still manages to look better than almost all of the other movies in Thorndyke’s book. It proved that if treated as something more than matinee fare, with a bit of money and some real talent involved, a fantasy movie could be something significant. Few of the remaining movies catalogued in this first chapter match up to the technical skill level of Milius’ film. The Beastmaster is a bastardized Andre Norton story, the rotoscoping in Ralph Bakshi’s Fire and Ice looks like the money-saving technique it was meant to be, and the less said about The Barbarians, starring identical twins Peter and David Paul, aka the Barbarian brothers, the better. Conan the Destroyer and Red Sonja, efforts to cash in on Conan the Barbarian’s success, failed due to lousiness.

The one movie out of the bunch that sounds interesting — because it sounds insane! — is Golok Setan (The Demon Sword) (dir. Ratno Timoer, 1984). It’s from Indonesia, is based on a comic by Mansyur Daman, and stars Barry Prima, one of that country’s biggest action stars. This quote from Thorndyke, without giving much away, conveys how awesomely over-the-top this one sounds:

The movie’s titular sword is forged from a meteorite by an old wizard. An object of great power, it is squirreled away in a cave and sought after by many, including the sultry Crocodile Queen (Gudi Sintara) who has a healthy sexual appetite and demands regular sacrifices. She dispatches the formidable warrior Banyujaga (Advent Bangun) to break up the wedding of a couple who have been somewhat lax with their offerings of late.

Banyujaga travels by floating rock to the wedding and unleashes hell on the assembled guests with much spurting blood and decapitated heads. The massacre is interrupted by the arrival of Mandala (Barry Prima), who fights Banyujaga, only to be thwarted by teleporting crocodile men. In the ensuing fray, Banyujaga escapes with the groom.

If I’m going to watch a cheesy movie, I want to watch that sort of cheesy movie.

Before examining Corman or the Italians, Thorndyke, in the chapter “Influence From Beyond the Stars”, turns his eye to sword & planet movies. Thorndyke makes the case, made before, that sword & planet is closely akin to swords & sorcery, really only exchanging broad swords for ray guns. These range from things like the camperiffic Flash Gordon (dir. Mike Hodges, 1980), to more high-end Hollywood fare like Highlander (dir. Russel Mulcahy, 1986), to the tamped-down sexism of screen versions of John Norman’s Gor (Fritz Kiersch, 1987) and Outlaw of Gor (John ‘Bud’ Cardos, 1989). Disheartening as it may be to learn about me, to be completely honest, of all the movies chronicled in Barbarians at the Gates of Hollywood, the only one I’ve ever owned and wanted to rewatch is Flash Gordon. It’s got a completely non-ironic sense of humor (yes, that used to be a thing in movies), a killer soundtrack, and, above all else, it knows that you cast Max von Sydow as one of the greatest pulp villains, not as some minor player who hires the hero (see Conan the Barbarian).

“Roger Corman Takes A Stab” is the aptly-titled third chapter. It’s the most fascinating from a how-movies-are-made perspective. Corman became well known for directing a series of movies based, however loosely, on Edgar Allan Poe stories starring Vincent Price. It was as a producer, however, that Corman became important to moviemaking. Under his guidance, hundreds of movies were made and numerous young directors — among them Francis Ford Coppola, Jonathan Demme, and John Sayles — were given their first chances. To get a sense of his approach to movie production, Corman’s own book about his career is called How I Made A Hundred Movies In Hollywood And Never Lost A Dime. If there were corners that could be cut or footage that could be repurposed to reduce the cost of production, Corman did it. These elements appear to be the hallmark of all the S&S movies he turned out in the eighties.

Sorceress (dir. Jack Hill, credited as Brian Stuart, 1982), was a disaster in Thorndyke’s telling. It was taken out of Hill’s hands and recut by Corman. Actors were dubbed by studio staff and there was insufficient special effects money. Despite the low final quality, it turned a profit. When Argentinian moviemakers Héctor Olivera and Alejandro Sessa approached Corman with a deal making movies in their country, he took it.

The first of Corman’s South American S&S ventures was Deathstalker (James Sbardellati, credited as John Watson, 1983). The story is the sort of substandard stuff found in lesser S&S stories, but it seems to have included levels of gore and sex most other movies had avoided. While it turned out to be one of the highest-grossing movies Corman ever made, it came at a time the film industry was changing and he was in bad financial straits.

In previous decades, the exploitation and genre movies that Corman excelled at had been the product of small independent companies. But ever since Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977) the big shots had begun to make the same type of movies as the independent studios, naturally injecting large amounts of financial backing with which smaller companies simply could not compete.

Barbarians at the Gates of Hollywood provides a detailed accounting of the changing nature of the low-budget movie industry. With the growth of big-budget genre movies, the death of the drive-in, and changing tastes, Corman and similar producers had to change if they wanted to survive. Thorndyke gives an excellent concise history of this transitional period for Roger Corman.

In addition to selling the distribution end of his company, New World Pictures, Corman amped up the production rate of his movies. Instead of overseeing every new movie as he had for decades, Thorndyke writes, Corman left that to others and the quality fell. Several starred the ill-fated Lana Clarkson (murdered in 2003 by Phil Spector), others David Carradine, and most were filmed on the increasingly decrepit sets in Argentina. Though they sound overall uninteresting, I am keenly curious about two: Amazons (dir. Alejandro Sessa, 1986) and Stormquest (Alejandro Sessa, 1987). Both movies were written with input from the late Charles Saunders.

The first is an adaptation by Saunders of his own story, “Agbewe’s Sword.” Though filming in Argentina forced the ditching of the original’s African-inspired setting, it does sound as if employing one of the bonafide greats of S&S resulted in one of the truest-to-the-genre movies ever made.

The second, according to Thorndyke in a message to me, is bizarre. Still, Saunders’ involvement is more than enough to entice me to watch it once, at least. The story, which Sessa came up with and Saunders scripted, involves warring Amazon nations, a lion goddess, and a men’s liberation movement.

Corman went on to produce several Deathstalker sequels and a series of Barbarian Queen movies. When his contract with Olivera and Sessa ran out, Corman moved production to Mexico. Reading the descriptions of his movies back to back, they sound like one magic sword after one loin-clothed barbarian after one scantily-clad princess after another. What it doesn’t sound like is anything other than many hours of cheap movies with very little effort at anything other than turning a quick profit for as little investment as possible. As the moviemaking environment continued to evolve away from one that allowed Corman to flourish, his attention turned from S&S and to other, even cheaper, types of movies.

The S&S movies documented in the chapter “Spaghetti Sword And Sorcery — The Italian Connection” arose from two elements in Italian filmmaking. The first was its own history of sword & sandal movies known as pepla films (plural of peplum, an over-the-shoulder Ancient Greek article of clothing). The second was a propensity to mimic trends in American popular movies. When director Franco Prosperi saw that Conan the Barbarian was being made, he rushed his own movie into production: Gunan Il Guerriero (Gunan, King of the Barbarians) (Francesco Prosperi, billed as Frank Shannon, 1982), starring veteran pepla actor, Pietro Torrisi (billed as Peter McCoy). Poorly paced, packed with a prophesied hero, Amazons, and dinosaur scenes stolen from One Million Years B.C., it doesn’t sound like it’s very good, but it beat Conan the Barbarian to Italian screens by a few days and made enough money to set the stage for a whole lot more movies.

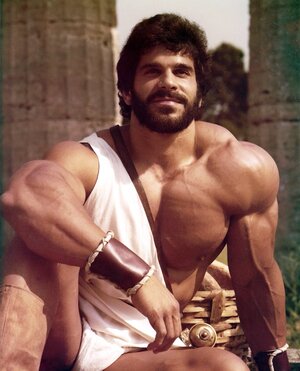

Aside from giving the much-loved Lou Ferrigno work in several Hercules movies, the Italian S&S movies sound like just a bunch of similar sword-swinging heroes, rubber snakes, and evil wizards often filmed at conveniently available local castles. Like Roger Corman, Italian directors were skilled at wringing every lira in savings out of production and, also like him, not above reusing footage and scores. When the money for special effects in the Lou Ferrigno-starring Sinbad of the Seven Seas (dir. Enzo G. Castellari, 1989) ran out, no one had any problem simply shooting new parts that negated the need for them at all. All of these movies sound like stinkers.

There have been a few attempts to revive the genre — or at least cash in on the popularity of the Conan character — but, the short-lived sword & sorcery movie industry pretty much died with the end of Italian S&S moviemaking. It dried up as the taste for such low-budget fare dwindled and “Italian cinema … found its feet again … A new generation of young filmmakers was returning some critical acclaim to Italian cinema in the early nineties.”

Barbarians at the Gates of Hollywood is a well-designed book, highly informative and, unlike most of the people involved in making the movies it covers, Thorndyke knows his way around the genre. His history of the rise and fall of literary sword & sorcery is spot-on. The conclusion, describing the drastically changing movie world of the nineties as well as the supplantation of written S&S by epic fantasy, is insightful. I didn’t spend five years reviewing S&S at Black Gate by accident. It’s a genre I like immensely and I’m still interested in its history and its cultural influence. If you have an interest in these movies as part of the entirety of sword & sorcery, which I do, this is an excellent shelf addition. But that’s also the extent of my interest. For the most part, I don’t want to watch these movies.

Thorndyke’s book is a valuable, wonderfully detailed history of S&S movies, but nostalgia is the only case than can be made for actually watching them. Maybe if I was fifteen again, cheap effects, thick-thewed heroes, topless women, and leering villains would make me want to rush out to the movies, but today it just doesn’t work. If I want a solid dose of the genre, I have shelves of books, old and new, to draw on. Except for two movies Charles Saunders wrote, none of these movies seems to have ever involved anyone who actually knew or liked the stuff that I’ve read, loved, and reviewed for years. Instead of Karl Edward Wagner or Robert E. Howard, it was mostly just low-budget hacks coming up with the most hackneyed and simplistic stories. Even the great John Milius and Oliver Stone couldn’t be bothered to stick to the source material. I admit I’m a bit of a purist concerning S&S. I take it seriously enough that seeing it reduced to stale and tired plots, mutton-headed heroes, and no atmosphere, I’m not satisfied.

I love low-budget midnight movies. When I was a teenager and my friends and I were picking a movie on a Friday night we pretty much insisted it have “cheap laser special effects.” Even something as ungood as Eliminators (dir. Peter Manoogian, 1986) has its appeal (though I’ll probably never watch it again). The 1980s S&S movies I’ve seen are a bad lot. Most lack even any sort of camp value to warrant at least an MST3K-style rewatch. I hold out hope that someday Robert E. Howard’s characters might make it to the screen in something approximating fidelity, but with the success of Game of Thrones, I suspect we’re going to get only epic fantasy for the foreseeable future.

Most of those movies were pretty awful. I think ‘Conan the Barbarian’ started out well, but the latter half was more like California in the Seventies than the Hyperborian Age. Another issue was. Schwarzenegger himself, and I’m not just talking about his limited acting abilities (it’s telling that modern film-makers use wrestlers – who are much lighter on their feet – rather than bodybuilders to play such roles). There were a few interesting experiments – remember ‘The Warrior and the Sorcereress’? An S&S riff on A Fistful of Dollars/Yojimbo, starring David Carradine? Sure it lost in the execution, but the concept was interesting.

One core problem is that Conan is a serial character, and serial characters don’t really have arcs, so a feature film might not be the ideal vehicle, but in general, these films suffered from a basic lack of taste, born – as you say – of contempt for the source material. No director came close to reproducing Howard’s lush, vivid prose on film, despite the fact that Howard’s prose is very cinematic. Go figure.

how DARE you!

Beastmaster is a great movie!

i’ll see myself out…

The soundtrack to Conan the Barbarian is WONDERFUL – I even used a short clip of, what think it is called ‘the search’ as our wedding march. I wish it was available on Spotify….

You can hate the Milius Conan movie; I know that a lot of people do and I understand why…but I love it. There are too many great moments for this purist to hold out against – Conan striking the chains off of himself with the sword from the tomb; Bill Smith’s speech about the Riddle of Steel (he absolutely nails it); Max von Sydow beautifully hamming it as King Osric; every moment of the great James Earl Jones; Mako’s “HA! Time enough for the earth in the grave”; Arnold clocking the camel (the best part is that the beast staggers for a second before dropping); Sandahl Bergman’s dancer’s body making you believe that she could survive as a roaming thief; the immolation of the Temple of Doom; and, as Barsoomia mentioned, holding it all together, Basil Poledouris’s brilliant score. I bought it on CD years ago and still listen to it regularly.

The sequel – now THAT I hate.

@Aonghus – For whatever reason, modern movies seem they must have some sort of character arc instead of just telling a cracking good yarn. Still, I hold out hope for a good REH movie some day

@silentdante – Ha!

@Barsoomia – The soundtrack is definitely grand

@Thomas – I get the love, but I can’t separate those moments from the unREHness of the overall undertaking. And, yeah, Destroye is magnitudes more awful

Thinking about it – in the unlikely event that I ever ended up directing a Conan movie – I’d pretty much depict Conan as a force of nature without much capacity for introspection. This would be in sharp contrast to the secondary characters (the evil wizard, the beautiful damsel in distress) who would be depicted as much more nuanced. They’d have arcs and maybe – just maybe – Conan would have learnt something new about human nature via these arcs, something he’d acknowledge with a thoughtful grunt before moving on to his next big adventure.

I would buy this book for its front/back cover design alone! “Please Be Kind Rewind”, indeed.

And I think that I have seen too many of these movies, but those Charles Saunders-scripted Argentinians do intrigue me, too.

My relationship with the Conan films is complicated. My first real exposure was Gary Gygax’ review of CtB in Dragon Magazine — he HATED it. I didn’t see the actual film until many years later and it’s possible that review colored my perception, but while I agree it’s EPIC (and has one of the all-time great soundtracks), I don’t think it’s particularly good as a story about Robert E. Howard’s Conan.

Destroyer I actually saw in the theater, and kind of enjoyed at the time; although it’s a pretty terrible film, it’s probably the closest we’ve come to a Conan film that actually feels similar in structure to a Conan story — at least a de Camp/Carter pastiche story or something. If only they would’ve ditched the “comedy relief” thief character.

I’ve also never been sold on Arnold as Conan — I think Jason Momoa’s performance in the (really dreadful) 2010 movie came closer to how I imagine Conan’s physical presence than Arnold’s kind of lumpen slab of beef.

If you ever have the opportunity to watch Deathstalker II, don’t, but do watch the bloopers during the credits. They’re hilarious.

Is it okay if I love the “enough talk!” fight in Conan 2 but not the rest of the movie?

Mixed feelings on the first Conan, but Ralph Bakshi has a funny bit about it on the Frazetta Painting with Fire documentary. Bakshi said when they talked to him about doing the film, he described a lithe, wolf-like Conan. “Basically, I gave them Frazetta.” But they already had Schwarzenegger.