Neverwhens, Where History and Fantasy Collide

Fantasy and Science Fiction are often viewed as two distinctive, though related, forms of speculative fiction, but in reality, the genre is a continuum in which the dreamscapes of a Lord Dunsany or Robert Holdstock can lead us through twisting turns of possibility until we arrive at Andy Weir and Ian Banks, or a Neal Stephenson story of “digital resurrection” can turn into a story of gods, goddesses and quests.

The central theme, the true “Call of Cthulhu” behind good speculative fiction is not “swords, sorcerers or blasters,” but the author’s ability to take the reader out of the comfort of our mundane world, and by introducing varying degrees of what-ifs, neverwhens or neverwheres to take us on inward journey that stimulates our imagination, our sense of wonder, our ability to consider this spinning rock we live on today. Of course, what I am talking about is “world-building.” The world building may be subtle, introducing only the smallest tweaks to reality, or it may be the all-encompassing sweep of foreign lands, peoples and languages, most famously represented by Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings.

There are a lot of ways to tackle world-building, but this column is going to focus on one: historicity in fantasy fiction. Full disclosure: I have a background in medieval history and have spent most of my adult life meticulous reconstructing medieval martial arts from primary source material. So, I’m a nerd. For the average fantasy reader, an obvious pushback is “it’s fantasy, Greg, what does it matter?” I am glad I asked for you!

- Representation, Appropriation and Stereotyping

These are current and growing concerns, particularly so in the literary world. I absolutely believe that when writing about real cultures or periods, or thinly disguised fantastical ones of the same, we have an obligation to write them realistically. Rightly or wrongly, large numbers of adults derive their perceptions of history from film, TV and novels, and while most people will never mistake the Skull Islanders of King Kong for real Polynesians, many will assume the Mayans in Apocalypto faithfully represent a blood-soaked, degenerate culture, whose put-upon neighbors were “saved” by the Spanish arrival. (Never mind that arrival triggered one of the largest cultural genocides in history, killing roughly 9 in 10 people in the Yucatan, destroying hundreds of thousands of manuscripts and melting down countless gold and silver artifacts. Pesky history!)

- Realism vs. Modern Sensibilities

I just finished rereading Rafael Sabatini’s Captain Blood short stories, which were written in the 1930s. In one of them, Blood sets out to help a slaver get back the money he lost when the governor of Havana swindled him on a load of African slaves. Blood — himself an escaped slave — doesn’t identify with the captive Africans at all and sees no problem with helping this “honest Englishman” get his due.

On the one hand, Rafael Sabatini is portraying the 17th century faithfully. On the other, we are living in a world still torn by post colonialism problems and racism is often on our minds. Peter Blood is being portrayed realistically but can I – as a 21st century American – relate to that, or does the episode take me someplace too far? Did the story even need the swindled trader to be a slaver, of all things, in order to work?

A converse trend in modern fiction is to present secondary worlds that are structurally just like Imperial China, or Rome, or the ubiquitous “medieval Europe”, but where whaddya know, despite being filled with Bronze or Iron Age monarchies, socially everyone thinks and acts with the mores, values and ethics of modern Americans or Europeans. That’s a valid choice, but for good world-building you should have a reason why. Example: In most low-tech, agricultural societies, the only real social insurance and retirement policy is multi-generational families and a high birth rate – if there is no division of gender roles, and queerness is perfectly normal and acceptable, even for the monarch, how does your otherwise identifiably medieval society work around its lower birth rates? How does it handle inheritance? What else would that change?

Note, I am absolutely not saying that authors shouldn’t write such worlds! Quite the contrary – various real cultures throughout history have indeed faced these same decisions and come to interesting solutions – just not necessarily ones that lead to modern Western society, which starts with a premise of Judeo-Christian ethics, modified by a world view increasingly dependent on technology to make feasible. Does a world built on Roman stoicism, which on the one hand might be more colorblind, but which has no sympathy what-so-ever towards slavery or poverty, lead to the same place?

|

|

|

Covers by Pablo Gerardo Camacho, Karla Ortiz, and Sam Weber

- It makes for a better, more cohesive story.

Think about the secondary worlds that really stand out for you. Whether it’s old standbys like the The Lord of the Rings or Dune, something fresh and new like the African-inspired worlds of Black Leopard, Red Wolf, The Rage of Dragons or The Sorcerer of the Wildeeps, or the Asian-inspired settings of The Grace of Kings and The Poppy War, what makes these worlds live is the depth and consistency of their own logic. You, as the reader, may not know or care that Guy Gavriel Kay’s Sarantium is Constantinople, his Serressa is Renaissance Venice, or Arbonne a stand-in for the 12th century Aquitaine, but his novels feel like historical fiction (and sell well) because they feel real to the reader.

Put another way, I can enjoy an RPG tie-in novel as well as anyone, but we don’t usually see secondary literature that analyzes Warhammer warfare in light of the real middle ages, uses the Forgotten Realms to explain the history of Scotland or fact-checks the historical basis of Golarion – all as has been done with George RR Martin’s A Song of Fire and Ice.

Some people do these things well, be they writing low fantasy, high fantasy, or even comedic fantasy. Some older writers do it surprisingly well, frankly, notably better than our contemporaries, while others – such as the legendary Robert E. Howard – were surprisingly careful with historical consistency when writing historical fiction, but were all over the map when writing fantasy — yet somehow it all works. Why? That’s what I hope we’ll find out!

This isn’t much of a column if I tell you this is all so very important and then wait a month to give an example, so in honor of Christopher Tolkien, who died this month, let’s take a look, not at his father’s famous work, but rather than film adaptation of it which he loathed so deeply, and how – as visual media – in many ways it succeeds where a more literal treatment to the source might not have.

When Peter Jackson was making The Lord of the Rings trilogy, he repeatedly told the designers, set-builders, prop-masters and actors that they weren’t making fantasy films, they were making an historical film set in Middle Earth. Whether one loves or hates the movies (and if we include The Hobbit adaptation, I can put myself in both categories), you can see how they approached this vision in regards to costuming, weapons and armour, even the larger aesthetics and movement styles of the different races. (For those who want to read a little of the process that went into figuring out what “orc” aesthetics were, see if you can find a copy of The Lord of the Rings: Weapons and Warfare by Chris Smith.)

As any Rings nerd knows, the Fellowship opens in the waning days of the Third Age, 3021 years after the Last Alliance of Men and Elves, which occurs about a century and a half after the sinking of Numenor, the greatest civilization of men, which had a three-millennia run itself. Tolkien used the biblical conceit that “in the elder days, men were longer lived, and have since dwindled,” so we might expect that a world dominated by immortal elves and men who would live three or four times as long as ourselves might evolve much more slowly technologically. (In our own, real world ancient Egypt had a 4,000 year-run, as did the civilizations of Meso-America, and while there was certainly innovation and adaptation, the daily life and experience of the common man at the end of those eras was only subtly different than it hand been three millennia before.)

An Anglo-Saxon scholar writing a self-conscious “mythology for England” Tolkien modelled his fictional warfare on the early and High Middle Ages periods of history, with an emphasis on Anglo-Saxon culture up to the time of the Norman conquest. The warcraft of Middle Earth is well established in the very first complete tale he wrote: The Fall of Gondolin, wherein the Elves of Gondolin use mail armour with long skirts, single-handed swords, shields, spears, axes and simple bows. There isn’t a crossbow, composite bow or piece of plate armour to be seen, and the overall presentation would have fit right in with the Norse Sagas that inspired it. As far as we can tell, these are the same weapons that all the races of Middle Earth wield in the First Age….

…and continue to wield for three thousand, four-hundred years in the Second Age…

…and then three thousand more years before we get to The Lord of the Rings. Meaning that there is absolutely no material evolution in the warcraft of Middle Earth for six and a half millennia. Apparently, all the invention and innovation happens in the First Age, at the hands of elves and dwarves, which skill was passed on to men, who become quite adept at its mimicry, but not its development:

Some metals they found in Númenor, and as their cunning in mining and in smelting and smithying swiftly grew things of iron and copper became common. Among the wrights of the Edain were weaponsmiths, and they had with the teaching of the Noldor acquired great skill in the forging of swords, of axe-blades, and of spearheads and knives. Swords the Guild of Weapon-smiths still made, for the preservation of the craft, though most of their labour was spent on the fashioning of tools for the uses of peace. The King and most of the great chieftains possessed swords as heirlooms of their fathers; and at times they would still give a sword as a gift to their heirs. A new sword was made for the King’s Heir to be given to him on the day on which this title was conferred. But no man wore a sword in Númenor, and for long years few indeed were the weapons of warlike intent that were made in the land. Axes and spears and bows they had, and shooting with bows on foot and on horseback was a chief sport and pastime of the Númenóreans. In later days, in the wars upon Middle-earth, it was the bows of the Númenóreans that were most greatly feared. “The Men of the Sea,” it was said, “send before them a great cloud, as a rain turned to serpents, or a black hail tipped with steel;” and in those days the great cohorts of the King’s Archers used bows made of hollow steel, with black-feathered arrows a full ell long from point to notch.

“Description of the Island of Númenor,” Unfinished Tales

In the roughly six hundred years of the First Age the races rapidly evolve from a stone-age to an early medieval technology. But by the time of the Siege of Minas Tirith, sixty-four hundred years later, the only notable innovations are some greaves, vambraces, and surcoats. If the armies of the Last Alliance of Men and Elves look as if they walked out of the year 1000, the Gondorian army at Pellenor Fields looks like it is from England, c. 1200.

Now, let’s forget about the plausibility of this for a moment, and remember that Tolkien very much is weaving a mythic history, much as medieval people dressed ancient Romans and Israelites in contemporary dress in their artwork. We know about Numenor’s antiquity, the superiority of its ancient craft and that the world is grown decadent as the “strength of men fails”, because the Professor tells us so, repeatedly. We know that the “modern” Third Age is a shadow of the Second, and the stagnation and lack of technical change in the arms and armour can be seen as symbolic of that.

But a film can’t convey this without narration or constant exposition masquerading as forced dialogue. And yet, it needs to convey the sweep of centuries. So, relying on the guidance of John Howe – who besides being a famed Tolkien artist was also a meticulous historical reenactor – Jackson does something different; he abandons Tolkien’s armaria by introducing plate armour, and the weapons which accompany it, displaying more technological diversity than mail shirts.

Gondorian craft is an imitation of Numenorian craft, which in turn, as I quoted above, derives from that of the Eldar. We can see this visually in Jackson’s film world:

Elven Armor of the Second Age,

ala Jackson. Decidedly fantastical,

with a naturalistic design,

but note the helmet.

Numenorian exiles of the Second Age, ala Jackson. Note the reference to the Elven helmets, but the armor lacks

the close fitting refinement. Honestly, the lower image of the “average” Gondorian of the Second Age is probably

the closest to how Tolkien himself envisioned the defenders of Minas Tirith.

Gondorians of the Third Age, ala Jackson. Again, you can see how the Numenorean gear grew into the Gondorian,

which is overall more protective: a complete harness of plate armour, in many ways closer to the ancient Elven

armor in its completeness, but lack its sinuous grace. (Rather like men vs. elves, themselves.)

The transition of Gondorian armour: King Elendil at the end of the Second Age, King Elessar (Aragorn) at the end

of the Third, and Gondorian armour of the late Third Age. Elessar’s armour is a more refined version of Elendil’s.

While this is somewhat impractical martially – the king is less well-armoured than his knights – symbolically,

the idea is to tie the new monarch to the last rule of the United Kingdoms of Arnor-Gondor. (Author side-note:

too bad the final design for Aragorn’s armour was less-complete and sophisticated than these designs.)

What’s more, the model for this continuum already existed in the real world! The opening of the ancient Etruscan tombs outside of Florence in the mid-14th century launched a new interest in antiquity, culminating in Humanism and that era we call “the Italian Renaissance.” This was as true of the martial arts as it was the poetic ones. Military theorists become interested in Roman authors and Roman battle formations, with a new emphasis on infantry, new weapons are designed to mimic the (believed) look and handling of ancient arms, even fanciful armours “ala antica” were designed for fighting in tournaments But the influence was found in practical war-gear as well, as the huge armories of Milan begin creating arms and armor inspired by classical sources, but adapted to the superior technology, and differing military needs, of their era.

Reconstruction of a Classical Greek Panoply, 5th – 4th c BCE. Source: Christian Cameron

Italian Milanese Harness, mid-15th century. Source: Wikimedia

Did Peter Jackson know all of this? I don’t know the man, but I rather doubt it. But he didn’t need to – and neither does the viewer. He simply needed to trust John Howe, who did know that, to work with the folks at WETA to use these inspirations to create something that would a) look like functional armour, b) reference each other, and c) would somehow convey an instinctual aesthetic of continuity in the viewers. See for yourself!

Middle Earth (Second and Third Ages) vs. “Fourth Age” Modern Earth (Antiquity and Late Middle-Ages/Renaissance)

Elven helmet. Source: Weta.nz

Numenorian Helmet, Second Age. Source: Weta.nz

Corinthian Helmets. Top: c 500 BCE. Source: Staatliche Antikensammlungen, (c) Wikimedia,

Public Domain; Bottom: c. 400 BCE, Source: Louvre, (c) Public Domain.

Gondorian Helmets, Third Age. Source: Weta.nz

Italian Barbuta, 15th c Italy. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, (c) Public Domain.

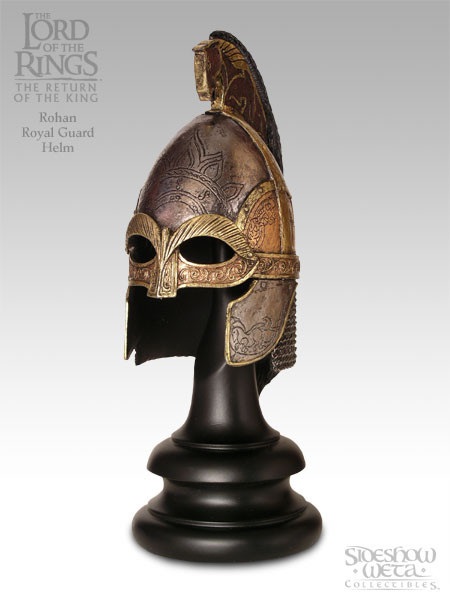

Rohirrim helmets, Third Age. Source: Weta.nz

Anglo-Saxon helmets. Coppergate Helmet, 8th century, (c) Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain; Reconstruction, 7th century, (c) Alamy.

Note the sense of design continuity and cross-reference – both to historical models and to each other. But the designers do one step better. Gondor in the Third Age is a dying realm lost in its own mythology and history, as its Steward slowly goes mad. Declining cultures often become increasingly baroque: making their war gear ever more elaborate in detail, even as it loses functionality. We see this in 17th century European armour, and we see it in Jackson’s Gondor, most notably in the Fountain Guard, who SHOULD represent the highest idea of Gondorian chivalry, but really represent its growing impotence.

Fountain Guard Armour, Third Age. Source: Wetz.nz/New Line Pictures. Think about it: Do you really want

to go into battle wearing a long cloak and with a giant handle on either side of your head? Probably not.

But truth can be as strange as fiction…scroll down….

Fountain Guard-meets-Rohirrim Lord: Polish Winged-Hussar armour, mid-17th

century. Although Poland was at its height of power, it was already starting to crumble

from within, and was attempting to invigorate and define itself through a myth of descent

from the ancient Sarmatians, reflected in the increasingly baroque look of its famed

cavalry’s armour. Spoiler alert: There are no leopards in Poland! (Nerd Alert: Check

out King Theoden’s body armour and then come back and look at the images here.).

Source: Polish Army Musuem.

An example of mid-17th c Dutch Cuirassier armour. Beneath all the etching, bluing, and goldwork,

note how clunky the armour actually is. Within a decade, all but the helmet, gorget (throat guard) and

breastplate would be discarded as impractical. Source: Roel Renmans

Finally, by making Tolkien’s beloved Riders of Rohan still have a basis in Anglo-Saxon design, but with additional pieces of a somewhat crude, splinted/leather plate armour, Jackson ties them to the Gondorians, and the idea that the two kingdoms represent two very different sub-races of Men (Tolkien’s term for humans). Once this design carries over into all aspects of the two cultures — the palace of Minas Tirith is based on the Duomo in Sienna, itself a wonder of 14th century Italy, whereas Theoden’s hall Medulsed in Edoras is obviously inspired by King Hrothgar’s hall in Beowulf, and the settlements of the Anglo-Saxons – you have a sense of cultural continuity and homogeneity that, even if the audience is ignorant of the sources, all seems to “fit”. We immediately know the difference between an Elf, a Gondorian and Rohirrim, and we can also tell that Gondor has seen better days. All without having someone stop and tell us.

And that’s what good world-building does: it reveals a new world to its audience and establishes a coherent series of rules for its cultures that the audience learns and instinctually respond to. Whether Jackson’s changes are faithful to Tolkien, and at what point “creative license” becomes subjugation of one creator’s vision for another’s, is a different, and very real, debate worth having. Here, we are restricting ourselves to the question of how to present a series of cultures and their evolution (or devolution) over the sweep of time in a visual medium. At that level, Jackson/WETA’s use of historicity to inform those decisions creates a truly cohesive whole.

Next month, we’ll look at the written word, and contemporary fantasy, when we see how 14th century knights, Arthuriana, Iroquois, talking bears, hermetic magic and truly terrifying dragons wrestle with… the complexities of devaluating currency and the fur trade in Miles Cameron’s Traitor Son cycle.

Greg is a native Chicagoan with a background in journalism and history. While in university, he began researching the martial arts of Late Medieval and Renaissance Europe. After working in marketing and corporate communications for a decade, he lost his mind and opened a small, non-fiction press (www.freelanceacademypress.com) dedicated to medieval studies, and opened Chicago’s only full-time European martial arts school to house the Chicago Swordplay Guild, which he had founded in 1999 (www.chicagoswordplayguild.com). As a fiction writer, in recent years he has published a growing number of short stories, and has the obligatory unpublished novel manuscript sitting on his hard drive.

Greg lives with his very tolerant family in the Chicago suburbs.

Excellent article! When one goes down the Tolkien rabbit hole it can be quite the fall! And don’t I know it! https://www.blackgate.com/2014/12/23/frodo-baggins-lady-galadriel-and-the-games-of-the-mighty/

Mele is being a bit modest in his bio: he has two stories published at Heroic Fantasy Quarterly. “Servant of the Black Wind” http://www.heroicfantasyquarterly.com/?p=2657 and “Kamazotz” http://www.heroicfantasyquarterly.com/?p=2799

Hi Adrian,

Thanks for the kind words and the call-out — indeed, a little bird tells me I may have one more to come over at HFQ! 😉

As to the rabbit hole — wow, that article was intense. That was some serious digging and linking of references, and also explains why Galadriel is the most “fey” of Tolkien’s elves — in many ways the one most like a Titania and Oberon: otherworldly with designs hard for a mortal to comprehend. There’s a clear reason she could both inspire and terrify. Great read!

amazing