Vintage Bits: Robert Clardy, Synergistic Software, and the Birth of the Personal Home Computer Role Playing Game

In 1978 Robert Clardy released his first computer game, Dungeon Campaign, for the Apple II. Dungeon Campaign, and Don Worth’s beneath Apple Manor, are widely regarded as the very first personal computer role playing games. While greatly inspired by pen and paper Dungeons & Dragons, there were no proven concepts or templates to work from, and it was very much a trial and error effort to figure out what features and elements would work, and not least what was achievable with the limited technology at the time. Today these pioneering games might seem extremely primitive and somewhat quirky, especially from what we now perceive as the standard template in computerized versions of role playing games, but at the time they were truly innovative.

In the mid-’70s computers, how they were used, and who had access to them, started to significantly change. The landscape was starting to move away from mainframes, which took up entire rooms or even floors, to hobby kits that with the right skillset could be turned into a more or less useful (or useless) device, to an environment where non-technical users could buy an off the shelf personal computer powerful enough to run somewhat sophisticated software.

This change in computing can very much be credited to the 1977 Personal Computer trifecta, the year we tend to refer to as the birth year of the personal computer as we know it. It was the year Commodore, Apple and Tandy Radio Shack all released their own take on accessible personal computers. These machines were not only powerful enough to be useful, they were also mass-produced and marketed to the average consumer, who frequently lacked the technical skillset earlier machines required.

The advent of computer role playing games, especially on mainframes and later personal computers, has its roots in the remarkable human nature to innovate – making machines do something they were never intended for. People with access to these mysterious computer colossuses quickly saw the potential for more than just boring analytics and data-crunching.

While action games, like Space War, had been lurking in the depths of mainframes for years, a cultural phenomenon in the mid to late ’70s would sweep across continents like a 15th-century plaque. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson’s fantasy tabletop role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons, released in 1974 and later expanded with the more rules-heavy Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, became the hottest thing around for boys and adults alike. Coupled with the renewed interest in J.R.R. Tolkien, it was inevitable that fantasy and D&D would become a major inspiration for a new generation of games written for mainframes. A myriad of dungeon crawlers and Multi-User Dungeons would soon be scattered across mainframes at universities, large companies, and even research facilities.

Dungeon & Dragons took concepts from earlier wargames, but instead of vast armies and a birds-eye approach, it individualized characters, focusing on single unique roles. Players now had the ability to adapt to a specific role (typically Fighters, Magic users and Clerics), each given different abilities and limitations by the roll of the dice. These abilities greatly impacted how characters coped with different challenges and scenarios throughout the game. With these role playing features the appeal of the games greatly increased, giving players the ability to live out and to an extent identify with their “virtual” characters. I think most people who have played role playing games recognize how their characters become somewhat of a fantasy extension of themselves. Feeling a deep connection – pain, anger, and joy — all through their character in the game. Many players would have a character for months or even years.

The amount of bookkeeping a typical game of D&D required made it a perfect candidate for an automated process, and it wouldn’t be long before people with access to computers, typically programming students, started writing simple programs to help with this cumbersome and tedious process. This, of course, quickly evolved into programmers writing their own games, most built upon the features and rules of pen and paper Dungeon & Dragons.

Robert Clardy

Robert Clardy had, like many early home computers pioneers, been exposed to computers and programming in the early ’70s. Not only through his interest in science, which led him to take an introductory programming course the summer before college, but more significantly during his time at Rice University in Houston, Texas, where he doubled majored in Electrical Engineering and Mathematical Science, both of which had a curriculum tied in with programming and computers.

While today we think of computer courses being in front of an actual computer, typing in data and immediately receiving output, this wasn’t the case in the early ’70s. Programs were written by hand and then punched onto cards… hundreds of cards, which all were carefully handed over to the computer operator and then fed into a punch card reader. If you were lucky and you’d written your program flawlessly you would, days later, hopefully, receive the anticipated output; if not, you’d start all over.

As a student, you didn’t have access to the computer itself, which were typically stored away in basements or in closed-off rooms. All system operations were the sole province of computer operator(s).

In Clardy’s junior year Rice University acquired an IBM System/360 mainframe, and unlike the earlier Burroughs 5500 mainframe, the new IBM system came with dumb terminals. Programmers now had the ability to much more easily write, run and test code in real time (or close to it). In Clardy’s senior year the system expanded to include video terminals that displayed output on a screen instead of through a teletype and printer. These displays delivered text and also simple graphics in the form of lines and points (ASCII graphics).

Clardy, in his senior-level course project in 1973, decided to produce a small 1-minute animated computer-generated movie, years ahead of the first commercial movies with serious computer-generated images.

Clardy’s early interest in computer graphics would, later on, be a driving force in his games. His first title was one of the first commercially third-party-developed Apple II games to feature graphics.

In 1974, after graduating from Rice University, Clardy got a job as an electrical engineer with Boeing at the Johnson Space Center, which at the time was providing tech support for the Space Shuttle program. Clardy stayed with Boeing for a number of years, and while he worked on interesting and complicated electronic circuitry, his passion for programming wasn’t being fulfilled. Programming jobs at the time were not only extremely scarce, they were also very much tied into the stiff and uncreative world of business, statistics, and data processing culture.

In 1977 Clardy and his wife Ann moved to Seattle, where he would work on the AWACS (Airborne Warning And Control System) radar program as a liaison engineer with Boeing.

The Personal Computer

Clardy’s first exposure to personal computers came when a friend purchased the newly released TRS-80. Clardy, while intrigued, still found personal computers too limited to pursue his dream of programming immersive games.

The same year the original Apple II was released with color display. But with only 4kb of memory, Clardy felt it also would be pretty much useless for complex games. Finally, in 1978, Clardy bought his first computer, an upgraded Apple II with 16kb of memory, knowing it could help achieve his vision for complex and immersive games.

Shortly thereafter, Clardy started to type in games from various published sources, but quickly decided that he needed to learn more about this powerful machine on his desktop.

The holy Apple II bible, the Apple II Reference Manual, also known as the Red Book, came with the computer and provided great insights into the inner workings of the computer and its features. The Red Book also included six games to type into Steve Wozniak’s Integer BASIC. One was called Dragon Maze, an interesting name for a game indeed. Clardy, the avid and passionate D&D player and lover of science fiction and fantasy, was quickly drawn to the magic behind the name and its many lines of code.

Dragon Maze consisted of a procedurally generated dungeon which you had to find your way through, all while being chased by a dragon.

While keying the game into the Apple II’s memory Clardy, would began to modify, add and rework much of the code. From Dungeons & Dragons Clardy had discovered that creating and directing games as a dungeon master was much more appealing than actually playing. This was the perfect starting point from which to create a more elaborate computer game.

Dungeon Campaign

While the limited capabilities of the personal computers typically resulted in simple action games, Clardy wanted to create a game that would adopt characteristics and features from Dungeons & Dragons. He wanted his game to have more complexity, more monsters, more advanced combat schemes, and of course graphics… all in one package.

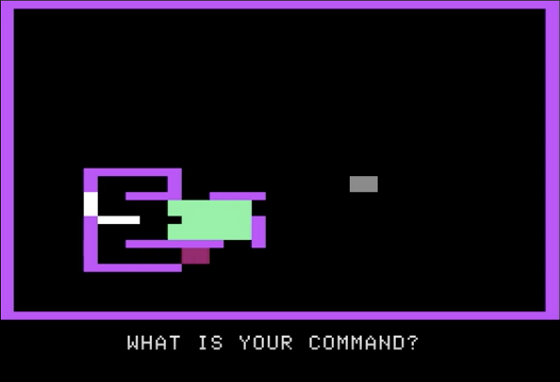

Modifications to the Dragon Maze code eventually led him to create something completely new, and after three months of work, Clardy’s first game Dungeon Campaign was completed. Like Dragon Maze, it featured randomly generated dungeon mazes and four levels, each with different challenges. You had to explore each maze and find treasure, all while engaging in combat.

Clardy added two unique characters, an elf and a dwarf, both with special abilities to help you throughout the game, and 13 human warriors to the player’s party. Each character in the party added to its overall hit points and strength, calculated by different factors. Lose a character and your party’s hit points and strength would drop. The game ended either when you had no party members left, or when you found your way out of the dungeon.

The random generation of the four mazes in Dungeon Campaign was a painfully slow process,

but instead of having the player stare at a loading screen, Clardy made the generation visible,

giving the player a small window to map out the dungeons on paper.

Even though Clardy wanted to have Dungeon Campaign encompass more, the 16kb of available memory was quickly exhausted, and he had to consider the game finished.

With his new game complete, and while still working at Boeing, Clardy started selling Dungeon Campaign under his Synergistic Software label, through a few ComputerLand stores in December of 1978.

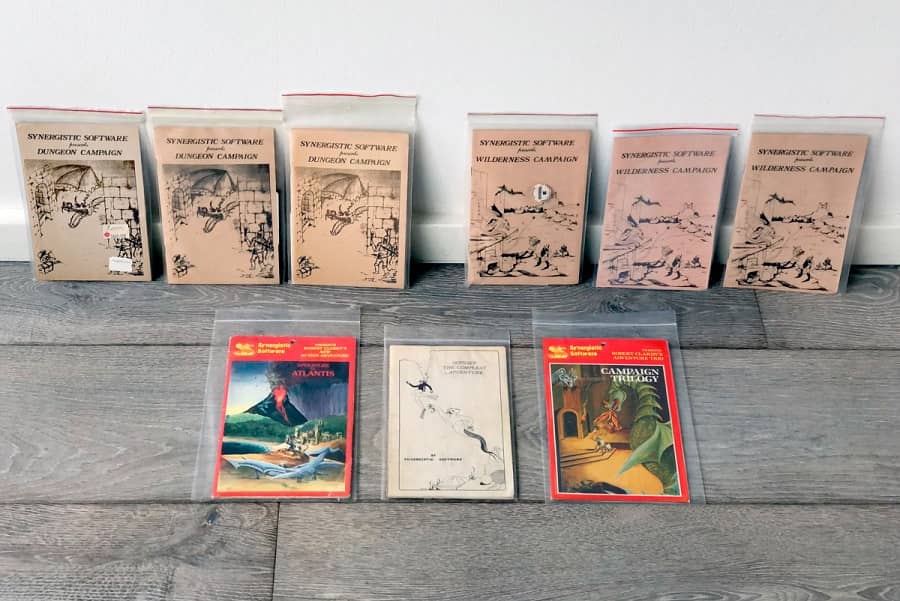

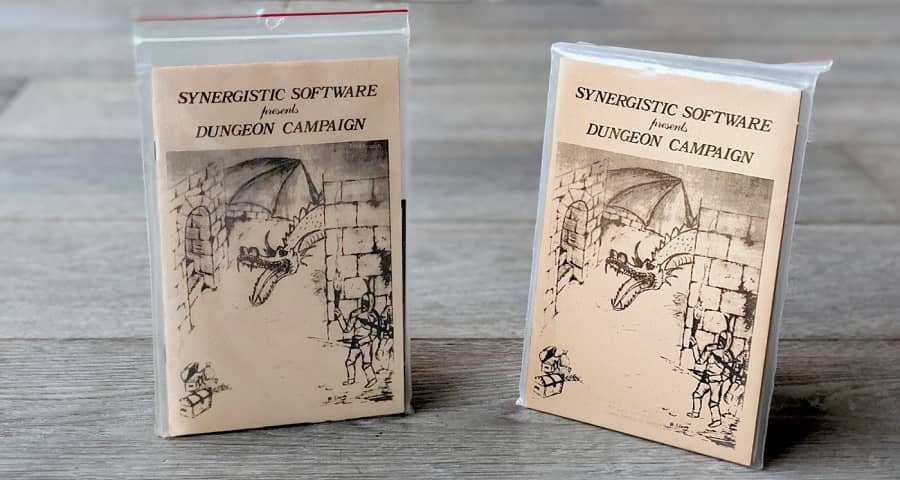

Dungeon Campaign was initially released on cassette in a ziplock bag, with a hand-drawn image by Clardy himself on the cover of the two-page manual.

After a few months Clardy had only sold a few dozen copies, but sales started picking up when he bulk mailed other Apple II stores.

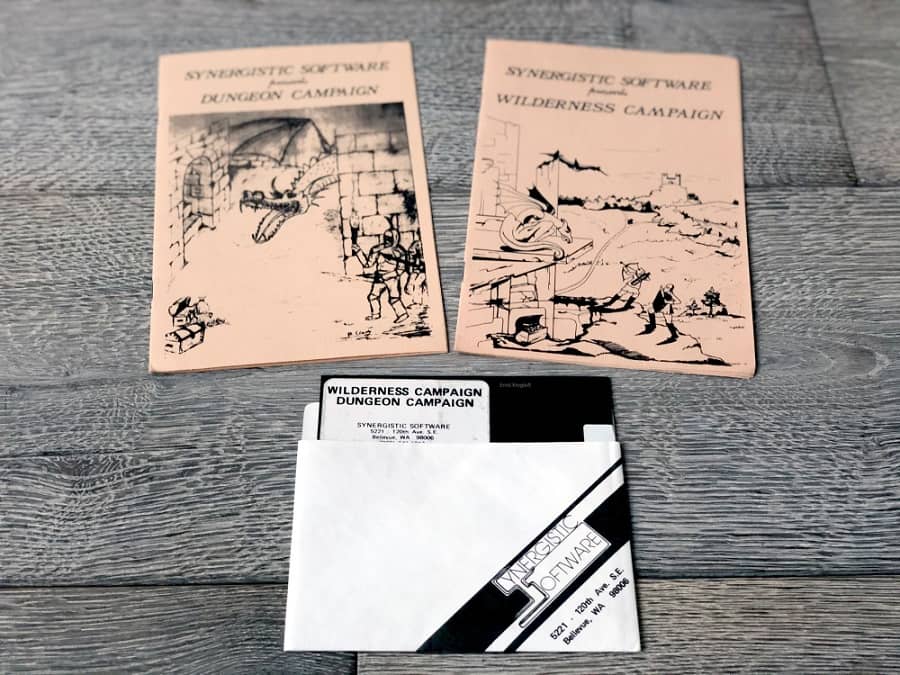

The original Integer BASIC Dungeon Campaign for the 16k Apple II released on cassette in December of 1978.

Because of the unreliable nature of data cassettes at the time, Clardy copied the game 3 times to each

side of the cassette. The cover art was done by Clardy himself.

Dungeon Campaign, floppy releases.

On the left the Apple II Integer 16k version, on the right the Apple II Applesoft 48k version

Wilderness Campaign

As both his skills and the technology capabilities grew, so did Clardy’s ambition, and with Dungeon Campaign finished he began working on his next title. While somewhat dissatisfied with how memory limitations defined the scope of his game, he wanted it to feel a bit closer to his pen and paper Dungeon & Dragons experience, with more role-playing features, more possibilities, and of course a switch from lo-res to hi-res graphics.

|

|

The advance from Dungeon Campaign’s lo-res 40×40 mode (40×40 graphics with four

lines of text at the bottom) to Wilderness Campaign’s hi-res 280×192 mode

Wilderness Campaign would feature large outdoor environments, with randomly placed villages, temples, tombs, ruins and abandoned castles. In the villages you had the opportunity to hire troops or buy equipment and weapons for your party, in preparation for your upcoming struggles against evil.

The goal of the game was to gather enough gold to hire and outfit an army, find the Sanctuary of the White Mage and receive a powerful device to defeat the Great Necromancer, who for ten years had been terrorizing and devastating the kingdom.

The first release of Wilderness Campaign was still written in Integer BASIC, which made it compatible with both the Apple II and the newly released Apple II+, though it quickly became apparent that Integer BASIC would crash when the player’s gold exceeded 32,767 (the largest number Integer BASIC could handle). To overcome this issue, the initial Integer BASIC game was rewritten in Microsoft’s Applesoft BASIC by David Dickens who, at the time, unlike Clardy, had an Apple II+. The cover also received new and somewhat professional artwork as well.

The Apple II+ was released with 48kb of memory and Microsoft’s Applesoft Basic in ROM, which allowed for different high-resolution graphics modes. Since Applesoft didn’t include any tools to easily generate shapes in high-res mode, Clardy developed his own tool, which later would become Higher Graphics, a commercial product of Synergistic Software.

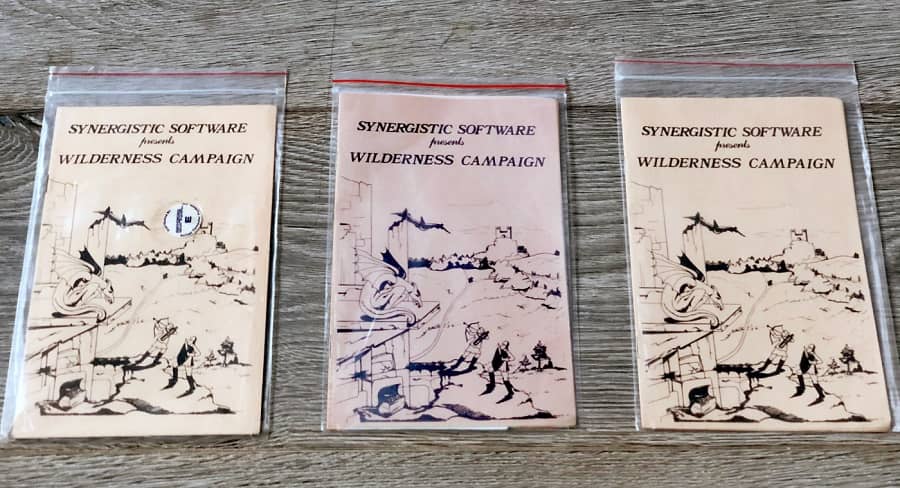

Wilderness Campaign, released in 1979. On the left the original cassette, in the

middle the Applesoft 48k version and on the right the Apple II 16k version from

the Dungeon Campaign/Wilderness Campaign bundle

With Wilderness Campaign finished in the summer of 1979, Clardy ended up quitting his job at Boeing to fulfill his ambition of turning his hobby into a full-time job. At the time there was literally no publisher to market or distribute third-party developed games. Generating sales meant spending lots of time contacting stores and otherwise administering the business, no to mention providing customer support. Juggling all that with a full-time job at Boeing and studying for an MBA in the evenings wasn’t feasible in the long run.

For the first few years Clardy would work from his basement in his Seattle home, and as time went on and the business grew his wife Ann would join him to help with packaging games and administrative jobs.

The Dungeon Campaign / Wilderness Campaign bundle, released for the Apple II in 1979.

Odyssey: The Compleat Apventure

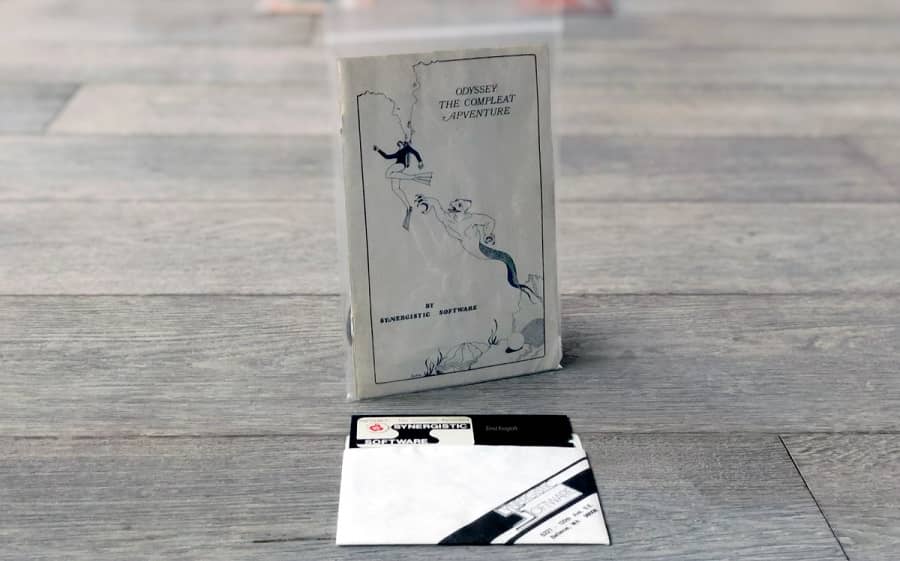

Odyssey: The Compleat Apventure was Clardy’s next endeavor and first floppy-only-based game. It was much bigger than the two previous titles. It featured three scenarios to give a bigger and more epic experience, and combined elements from both Dungeon Campaign and Wilderness Campaign. History would quickly seem to repeat itself as he yet again ran out of available storage space, and had to consider the game finished. Some areas had to be stored in lo-res graphics, and the ending was shortened.

Odyssey: The Compleat Apventure for the Apple II 48k, released in 1980. While it may seem the title

was a serious misspelling, this was intentional – Apventure was Apple and adventure combined.

Odyssey left so many unfinished ideas that Clardy wrote Apventure to Atlantis as a sequel in 1982 to wrap up the loose ends. It ended up being too big for the available technology at the time, and had to be limited.

Apventure to Atlantis, released in 1982 for the Apple II

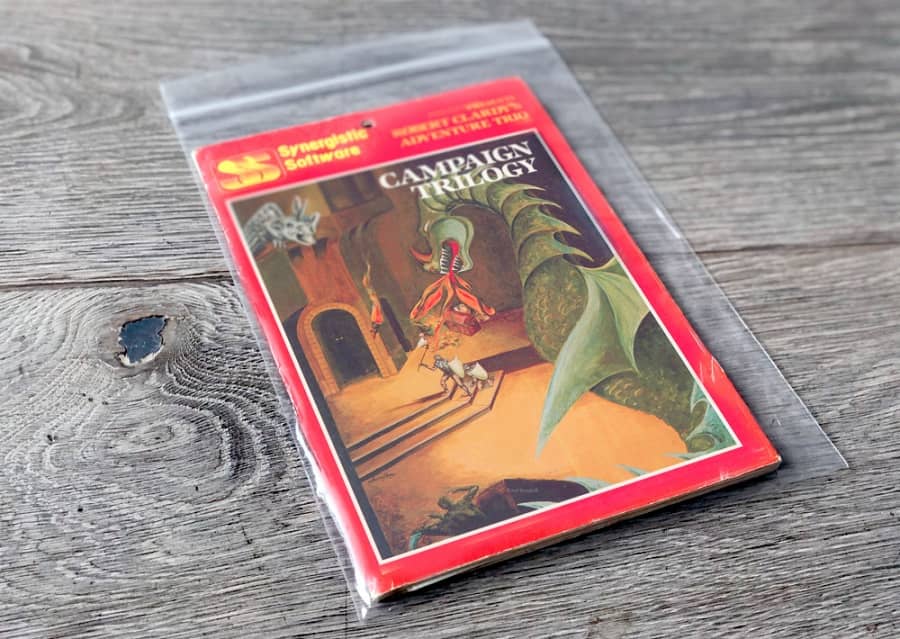

Campaign Trilogy, released in 1980 for the Apple II. This was a repacking of Dungeon Campaign,

Wilderness Campaign, and Sorcerer’s Challenge, another simpler game Clardy had written. Also in 1980,

Clardy started to rework Synergistic Software’s image, going for a more professional look. Part of this

was enhancing the packaging and cover artwork. The new cover artwork was by painter

Judy Swedberg, who also did the cover art on Apventure to Atlantis.

Through Clardy’s many games of Dungeons & Dragons he discovered that being Dungeon Master wasn’t all about winning and making it as difficult as possible for the players, but more about taking the players goals and preferences into consideration, and providing more exciting, balanced and long-lived gameplay.

Long term gameplay is available through repeat plays of radically changed games, not by making a single solution take weeks or months.

— Robert Clardy, in Brian Wiser & Bill Martens “Synergistic Software The Early Games”

Dungeon & Dragons was different each time you played it. Random elements combined with the action of the players to provide variety and replayability, something Clardy wanted to encompass in his games – very much ahead of his time. Adventure games of this era were very much linear, with one fixed path to one end goal. Developers typically made games unpleasantly difficult and introduced obscure puzzles, which at times required an infinite amount of guesswork to progress, just to add longer gameplay.

Many will probably recognize this pattern with most of On-Line Systems and later Sierra On-line titles. Also, adventure heavy hitters like Infocom and Adventure International were producing very much one-laned experiences around that time.

Clardy’s experience through pen and paper Dungeons & Dragons, his ability to take what he knew worked well and implement it, and his knack for pushing technology to the limit, made him a true pioneer. His work in many ways can be seen as a big part of the foundation for almost all adventure computer role-playing games today.

While Clardy’s and Synergistic’s early titles were truly pioneering, and introduced the roleplaying game genre to the personal computer, they’re pretty much unknown today, even by fans of the genre.

The early Synergistic titles were only released on the Apple II platform, and while that machine was successful and had a long lifespan it was, especially in the early years, heavily outnumbered by Tandy Radio Shack’s TRS-80.

Being one of the first in this small market meant limited exposure and sales. In just a few years the market for personal computers exploded and with that, games were suddenly being enjoyed by tens if not hundreds of thousands of people, all hungering for electronic entertainment. This earned games like Dunjonquest, Ultima and Wizardry much more fame and success. Leaving the early Synergistic titles, for the most part, relegated to a dusty place on the shelves of gaming history.

In 1979 Automated Simulations (later Epyx) would release their first CRPG, Dunjonquest – Temple of Apshai. Unlike Dungeon– and Wilderness Campaign, it was ported to every imaginable home computer, given it much more exposure. Apshai also introduced real-time gameplay, a more sophisticated combat system, and generally better graphics and more intuitive gameplay. Automated Simulations also understood that the primitive graphics weren’t always enough to establish the setting, and therefore added descriptions to every room in the manual.

So while most people tend to think of Apshai, Ultima or Wizardry when discussing the origin of the (personal) computer role playing game, it actually started years before with Synergistic’s Dungeon Campaign and Don Worth’s Beneath Apple Manor, which I might cover in another article.

Synergistic Software would go on to produce more than 160 titles in the next two decades, both games and utility software. Unlike many, Synergistic Software continued as an independent developer as the IBM/PC platform gradually became dominant. In 1996 Synergistic Software was acquired by Sierra On-Line but continued on as an independent development division. In 1999 Sierra started making organizational changes to streamline operations, which in the end meant that Synergistic was closed down for good.

Robert Clardy left his company in 1996 to pursue other interests.

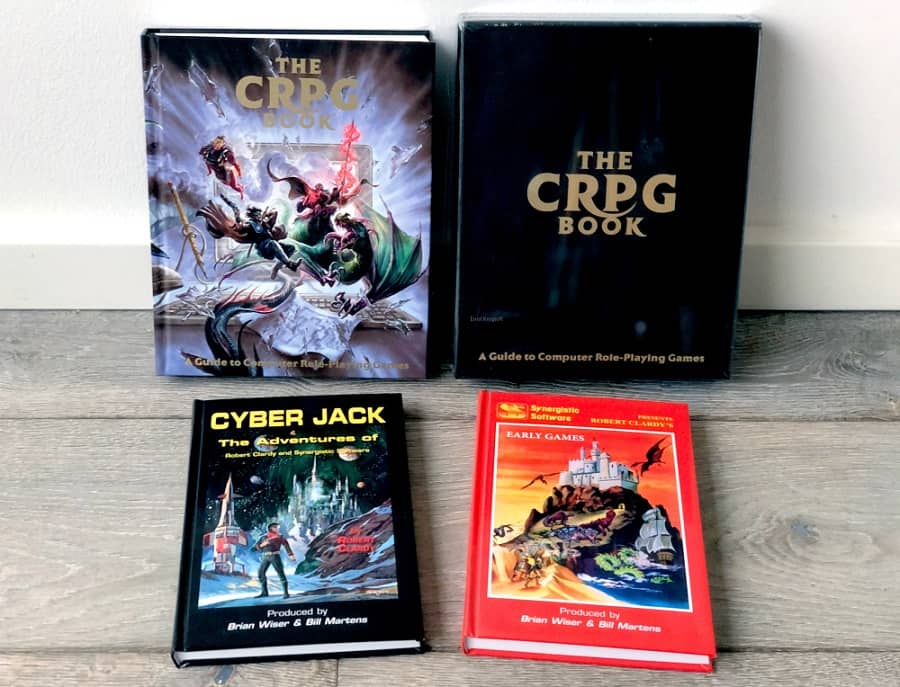

I can only recommend the A.P.P.L.E (Apple PugetSound Program Library Exchange) published titles:

Cyber Jack – The Adventure of Robert Clardy and Synergistic Software and Synergistic Software –

The Early Games, both by Brian Wiser and Bill Martens. Also, Bitmap Books gorgeous The CRPG Book,

while it only touches somewhat briefly on the very early history of CRPG, it does cover most known

CRPG’s between 1975 and 2015. The book is a great informative read with well-described pictures.

I’m thinking of doing a more general article about my other Synergistic titles from my collection sometime in the future.

Previous Vintage Bits articles at Black Gate include:

In Search of the Lost Black Crypt (2012)

Sword of Aragon (2013)

Lordlings of Yore (2013)

The Crescent Hawk’s Inception (2013)

Icewind Dale: Enhanced Edition Available for Pre-Order (2014)

TSI Kickstarter is Rebooting the SSI Gold Box Series (2015)

The 10 Greatest Dungeons and Dragons Videogames (2015)

How G.O.G. Rescued the Classic Forgotten Realms Computer Games (2015)

FTL — Faster Than Light by Ernst Krogtoft (2019)

Some Random Big Box PC Games: Wizard’s Crown, Thomas M. Disch’s Amnesia, Waxworks, Discworld II, The Coveted Mirror, Truberbrook by Stuart Feldhamer (2019)

Star Saga, an Innovative Hybrid Sci-Fi Computer RPG Series by Ernst Krogtoft (2019)

This article originally appeared at the Retro 365 blog.

Ernst Krogtoft lives in Copenhagen. He was an avid gamer in the ’80s. His father worked for IBM; they always had multiple systems at home, and Ernst became fascinated with the games and the technology at an early age. He’s been collecting vintage computer software for almost 20 years, focusing on titles from 1978 to 1994. Today he sees himself as more of a vintage games curator, taking care of earlier titles, and writing the stories of the people behind the games, and of a forgotten time. His blog retro35.blog is where he writes about his collection. His last article for Black Gate was Star Saga, an Innovative Hybrid Sci-Fi Computer RPG Series.

Thank you, Mr. Krogtoft, for this wonderful look back at a CRPG pioneer. I never found Synergistic or Mr. Clardy’s work in person, only remembering them from ads in computer magazines like Byte or Dr. Dobb’s. Temple of Apshai I remember from ads in Lou Zocchi’s Gamescience catalogs, of all places.

Me? I was using an Atari 1040ST, which box I kept running up to 1999.

I bought a copy of Synergistic Software and Synergistic Software – The Early Games very recently. It looks like a nice bit of early CRPG history.