Non-Compliant and Self-Aware: Bitch Planet

I can understand scepticism of consciously political art. But I feel it’s often misplaced. If an artist is choosing to create art about politics, it probably means that those politics have a deep power for them. Which in turn is probably because the politics are connected to their emotions, worldview, beliefs — all the things that give art power. A political theme doesn’t elevate a work of art, but good art can illuminate the political. An artist may create consciously political art because politics are their passion. A storyteller may find their politics are the lens through which to present human truth and artistic power.

I can understand scepticism of consciously political art. But I feel it’s often misplaced. If an artist is choosing to create art about politics, it probably means that those politics have a deep power for them. Which in turn is probably because the politics are connected to their emotions, worldview, beliefs — all the things that give art power. A political theme doesn’t elevate a work of art, but good art can illuminate the political. An artist may create consciously political art because politics are their passion. A storyteller may find their politics are the lens through which to present human truth and artistic power.

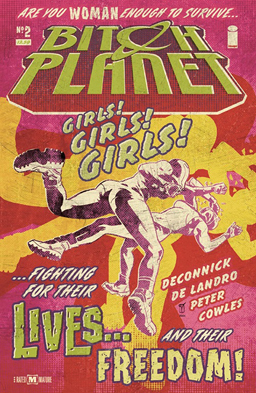

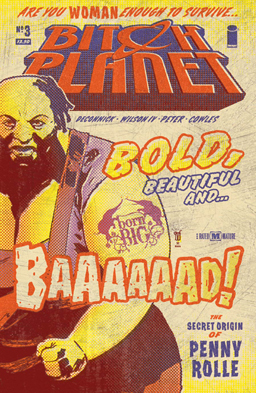

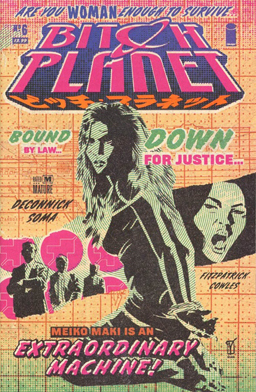

Which brings me to Bitch Planet, the creation of writer Kelly Sue DeConnick and artist Valentine De Landro. Some basic information on the book: it’s an ongoing comic published by Image projected to run at least thirty issues. The first five issues have been collected into a trade paperback, while the sixth came out earlier this month. Individual issues have bonus features including essays, letters pages, and selections of tweets and instagrammed pictures from readers. Cris Peter does the colours and Clayton Cowles the lettering; art for the third issue came from Robert Wilson IV, while Taki Soma handled the sixth. The series has built a devoted fan following and been very well reviewed — and it’s easy to see why.

Bitch Planet is set in a future with interplanetary (presumably interstellar) travel and 3-D holograms and an even greater media saturation than we have today. Patriarchy’s more blatant, an MRA extremist’s idea of utopia (naturally, therefore, everybody else’s dystopia). Women can be arrested for various kinds of “non-compliance” — things like “disrespect” and “emotional manipulation” and being a bad mother and, generally, not acceding to society’s expectations. One character’s crimes include “repeated citations for aesthetic offences, capillary disfigurement and wanton obesity.” The non-compliant criminals are exiled to an off-Earth prison, the eponymous “Bitch Planet.”

The book follows a group led by a prisoner named Kamau Kogo, who is given a chance to form a team to play the violent contact sport Megaton. Kam’s suspicious of the offer, but some of the other non-compliants convince her to accept — because they know a secret which means playing the game might also give them a chance at escape. The book follows the team of women as they fight; fight in the game, fight to survive the unjust system imprisoning them, fight to be who they are in the face of a society bent on crushing them. The book is blunt and lurid and action-packed, it is angry and funny and fun, and it’s deeply aware of gender and race.

The book follows a group led by a prisoner named Kamau Kogo, who is given a chance to form a team to play the violent contact sport Megaton. Kam’s suspicious of the offer, but some of the other non-compliants convince her to accept — because they know a secret which means playing the game might also give them a chance at escape. The book follows the team of women as they fight; fight in the game, fight to survive the unjust system imprisoning them, fight to be who they are in the face of a society bent on crushing them. The book is blunt and lurid and action-packed, it is angry and funny and fun, and it’s deeply aware of gender and race.

That plays out in who the characters are and how the setting works. The satire’s pointed and constant. The patriarchal society of the book, formed by clans from around the world and ruled by a group called “the Fathers,” lets DeConnick attack a range of targets. Religion’s bound up with the power structure and its unrelenting patriarchy: in this future the Earth is spiritually imagined as a father and space as a mother. More than that, the nature of the story means that DeConnick can take aim at the prison-industrial complex, at the importance given to (men’s) professional sports, at the false consensus created by a media in thrall to the powers-that-be, and even at things like ideologically-motivated pseudoscience (as a talking head on TV speculates that women megaton players suffer from an imbalance of “humours”).

The satire also works at a more granular, individual level. In the prison, most of the prisoners are people of colour. But so are many of the workers — they have a status above the inmates, but far below the bosses. On the other hand, the elite warrior who presents Kam with the chance to form her megaton team is a White woman who thinks the rulers of the world aren’t misogynistic at all: “Take me, for instance,” she says as a counterexample to an unimpressed Kam. On the other hand, the very first page of the series shows an unnamed, faceless working woman desperately trying to get to work on time before her male boss fires her; she makes it, and settles down to her job, recording propaganda tapes for indoctrinating prisoners. Throughout the series we see holograms from time to time, talking down to the prisoners and spewing propaganda, and so this opening gives us a glimpse of the structure that produces the holograms, the economic coercion underlying the society of the Fathers.

We therefore get an illustration of how women are made to be complicit in the oppression of other women through economic coercion. But that’s something the audience puts together for itself, consciously or unconsciously. The systemic forces underlying the scene aren’t highlighted; the drama is all, and the placement of the scene is what gives it resonance. Narratively, it’s a good intro, unsettling and unexpected, showing us the bits of the world without exposition. Generally, throughout the book the characters and who they are emerge naturally from the science-fictional environment DeConnick and De Landro create. The politics underlying the book are obvious, but never over-explicit. The story is the story, and there’s nothing predictable in the plot or character decisions.

We therefore get an illustration of how women are made to be complicit in the oppression of other women through economic coercion. But that’s something the audience puts together for itself, consciously or unconsciously. The systemic forces underlying the scene aren’t highlighted; the drama is all, and the placement of the scene is what gives it resonance. Narratively, it’s a good intro, unsettling and unexpected, showing us the bits of the world without exposition. Generally, throughout the book the characters and who they are emerge naturally from the science-fictional environment DeConnick and De Landro create. The politics underlying the book are obvious, but never over-explicit. The story is the story, and there’s nothing predictable in the plot or character decisions.

In fact, there’s nothing particularly predictable in the form of the thing, either. DeConnick’s said in interviews that the book was born in part out of a fascination with women-in-prison movies. She told Wired: “They set up these scenes with the intention of the viewer taking voyeuristic pleasure in the degradation of the woman, but then all is forgiven because she gets her revenge. It’s sort of the dictionary definition of exploitation.” So here DeConnick and De Landro undermine the exploitation in a number of ways, presenting lesbian scenes and shower scenes and the like as you’d expect to find them in an exploitation film, while subverting that presentation in a number of ways — how the scenes play out, how the women are presented visually, and at one point how a male voyeur (and thus the heterosexual male gaze in general) is made a part of the action.

More than that, this comic is hyper-aware of comics’ own historical association in North America with the lurid and lowbrow. It’s conscious of the comic as a pop culture artifact. It’s not afraid of screamingly bright colours, often used symbolically as an ironic comment on gender visual shorthand. Densely-packed covers are filled with promo text and taglines. Back covers have crass fake ads (and some real ads) and what looks like a subplot percolating through ambiguous personal messages. The overall sense of comics-as-they-used-to-be works both with the sense of grindhouse films the book evokes, and perhaps with the sleazy misogynistic sense of 1970s lowbrow culture in general.

That self-awareness is uncharacteristic of exploitation film, of course, but it’s typical of Bitch Planet. The exploitation overtones and the political awareness come together, as the craft of the creators plays with the first to bring out the second — without abandoning a bracing nastiness in what is often a very entertainingly violent book. The storytelling here is incredibly sharp. Dialogue is terse but real, and never overburdens a page; a lot happens in this book, but it happens quickly, and the story moves at a relentless pace. The page layouts have a classical feel not entirely unlike 1970s comics, with smaller panels and a dense reading experience. Inset panels may hold a line of dialogue or establish a beat of time. There may be eight or nine panels on a page here, a movement away from manga-influenced layouts and from the often-lazy “cinematic” approach of page-wide horizontal panels. Layouts also draw out symbolism; it strikes me that pages with scenes between high-level male characters have noticeably stricter panel grids than scenes in the prison, as though unrelenting patriarchal hierarchy was defining not just the relations between men but also the shape of their moments in the story.

That self-awareness is uncharacteristic of exploitation film, of course, but it’s typical of Bitch Planet. The exploitation overtones and the political awareness come together, as the craft of the creators plays with the first to bring out the second — without abandoning a bracing nastiness in what is often a very entertainingly violent book. The storytelling here is incredibly sharp. Dialogue is terse but real, and never overburdens a page; a lot happens in this book, but it happens quickly, and the story moves at a relentless pace. The page layouts have a classical feel not entirely unlike 1970s comics, with smaller panels and a dense reading experience. Inset panels may hold a line of dialogue or establish a beat of time. There may be eight or nine panels on a page here, a movement away from manga-influenced layouts and from the often-lazy “cinematic” approach of page-wide horizontal panels. Layouts also draw out symbolism; it strikes me that pages with scenes between high-level male characters have noticeably stricter panel grids than scenes in the prison, as though unrelenting patriarchal hierarchy was defining not just the relations between men but also the shape of their moments in the story.

More than that. The back pages and propaganda holograms and inset panels and all the other devices don’t just help move the plot, they establish background about the world, build character, and further develop the pervasive irony built into the comic. This is one of the more complex comics I’ve read lately in terms of its narrative approach, in terms of how each aspect of the book contributes to the story. It’s consistently clever, but never distracting and never hard to grasp. The craft involved is remarkable.

The book works in part because of that craft, and in larger part because that craft’s in service to a deeper vision. It’s a political vision, if you like, but all that means is that it’s an understanding of the world that includes the systemic aspect to human interaction and to the shaping of human personality. This doesn’t mean that characters become less individualised. I found the opposite happened, in fact. If the book argues that odds are stacked against an individual bound within an unjust society — well, then, the heroes here are in prison, which literalises the metaphor nicely. Bitch Planet is a sharp book, and a passionate one.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy a collection of his essays for Black Gate, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.