Fantasia Diary 2015, Day 1: Miss Hokusai and Ant-Man

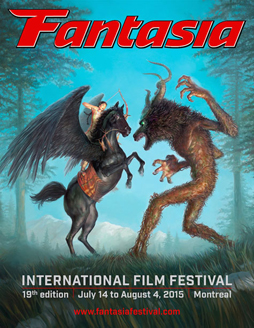

The Fantasia International Film Festival opened in Montreal on Tuesday night, and this year, like last year, I’ll be covering it for Black Gate. This will be the 19th edition of Fantasia, one of the world’s largest genre-oriented film festivals, and I’m looking forward to seeing a lot of movies. As I did last time, I’m planning to keep a diary-style record discussing the films I see and also recapping some of the special events around them — a lot of screenings are accompanied by presentations, or by discussions with the creators, and I’ll pass along my notes on those.

The Fantasia International Film Festival opened in Montreal on Tuesday night, and this year, like last year, I’ll be covering it for Black Gate. This will be the 19th edition of Fantasia, one of the world’s largest genre-oriented film festivals, and I’m looking forward to seeing a lot of movies. As I did last time, I’m planning to keep a diary-style record discussing the films I see and also recapping some of the special events around them — a lot of screenings are accompanied by presentations, or by discussions with the creators, and I’ll pass along my notes on those.

There are over 135 feature films being presented at Fantasia this year, and looking over the schedule it feels like I want to see almost all of them. The nature of scheduling makes that impossible, but I’ll be striving to look at as many as I can. I’ll be trying to catch films I miss in the festival’s screening room, where I’ll be able to watch them on a computer monitor. That’s a different experience than seeing a movie on the big screen with a crowd, but it’s better than nothing.

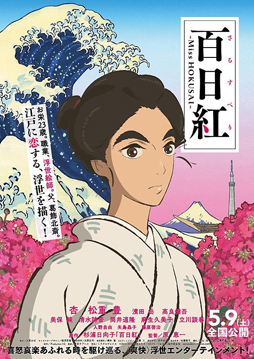

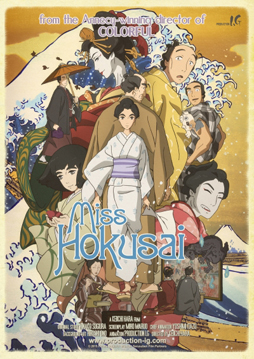

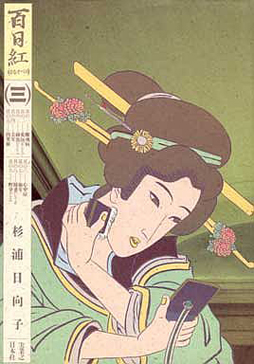

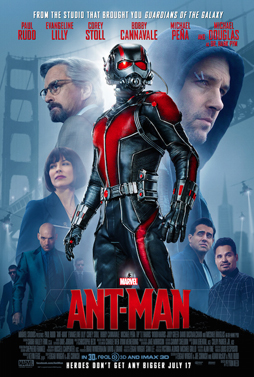

Two theatres at Concordia University’s downtown campus serve as the main venues for the festival this year, and on Tuesday I saw two films in the big Hall Theatre. Both movies were warmly received by the crowd, and both seemed to me to be great successes in very different ways. Both, as it happened, were adaptations from comics. The first was an anime called Miss Hokusai from Japanese director Keiichi Hara, an adaptation of Hinako Sugiura’s Sarusuberi, about the daughter of the famed 19th-century artist Hokusai and her relationship with her father. The second was Marvel’s Ant-Man, directed by Peyton Reed. I’ll have more to say about that further below (short version: it’s much better than I’d have imagined an Ant-Man movie could be, and instantly became one of my favourites of the Marvel movies). First, a look at Miss Hokusai, and Fantasia’s opening ceremonies.

The Hall Theatre was packed as things got started. When I took my seat the eleven months since last year’s Fantasia ended seemed to drop away: once again I heard the DJs from Concordia’s radio station CJLO playing warm-up songs, and once again was enveloped in the excited burbling of a crowd flooding in to fill the maroon-coloured seats of the Hall. One of the Fantasia directors (my notes say it was General Director Marc Lamothe) opened the proceedings by speaking to the crowd, noting that people had lined up for three hours outside — these were people who already had tickets, but were eager to get a good seat for the film. People who claim cinema is dying, he said in French, have never been to Fantasia. After thanking the festival’s sponsors, he introduced Isabelle Gauvreau, the director of the Festival’s Fantastique week-end du cinéma Québécois. Gauvreau in turn introduced the director of a short film preceding Miss Hokusai, Hughes Provencher, who took a bow before his film played. (To a chorus of meows from the audience when the lights first went down, as is Fantasia tradition.)

The Hall Theatre was packed as things got started. When I took my seat the eleven months since last year’s Fantasia ended seemed to drop away: once again I heard the DJs from Concordia’s radio station CJLO playing warm-up songs, and once again was enveloped in the excited burbling of a crowd flooding in to fill the maroon-coloured seats of the Hall. One of the Fantasia directors (my notes say it was General Director Marc Lamothe) opened the proceedings by speaking to the crowd, noting that people had lined up for three hours outside — these were people who already had tickets, but were eager to get a good seat for the film. People who claim cinema is dying, he said in French, have never been to Fantasia. After thanking the festival’s sponsors, he introduced Isabelle Gauvreau, the director of the Festival’s Fantastique week-end du cinéma Québécois. Gauvreau in turn introduced the director of a short film preceding Miss Hokusai, Hughes Provencher, who took a bow before his film played. (To a chorus of meows from the audience when the lights first went down, as is Fantasia tradition.)

Calamités Caustiques is a wry comedy about a single mother frantically running around Montréal trying to pick up her son after school. Assorted absurd events happen, and she has to deal with a variety of exasperating people. The characters are just human enough not to seem like caricatures, and lead Valérie Cadieux carries the story capably. The surreal humour is a little obvious, but works because it’s played absolutely straight. In all, the film feels shorter than its 14-minute running time.

Miss Hokusai was next. Another speaker from the Festival — I think it was Nicolas Archambault, one of Fantasia’s Directors of Asian Programming — observed that the film was playing for only the second time outside of Japan, after winning the Jury Prize at the Annecy Animation Festival. He then introduced director Keiichi Hara, in attendance along with scriptwriter Miho Maruo and the president of animation studio Production I.G. Through a translator, Hara said he was honoured to have his film picked to open the festival, and emphasised his respect for Hinako Sugiura, whose work he had adapted for film. “Let’s go to two hundred years ago,” he concluded in English.

Miss Hokusai begins in 1814, in Edo (modern Tokyo). O-Ei is the daughter of Hokusai, a great but slovenly artist. He encourages his daughter to follow in his footsteps, and the film is very broadly the story of her growth as an artist. It’s told in a series of anecdotes that flow one into another, revolving around various themes. O-Ei has various romantic or near-romantic interludes with young male pupils or rivals of Hokusai. She helps take care of her blind younger sister O-Nao, while Hokusai, terrified of death and illness, keeps O-Nao at a distance. Ghosts and dragons appear, not horrific but folkloric. Above all, O-Ei struggles with her art and with selling prints and with trying to become better. Like her father she tries drawing erotica — but the general consensus, at least among the men who see her work, is that while she’s extremely effective at drawing women, her males are copied from her father’s art. According to Hokusai, O-Ei won’t admit she hasn’t the experience needed to draw men.

Miss Hokusai begins in 1814, in Edo (modern Tokyo). O-Ei is the daughter of Hokusai, a great but slovenly artist. He encourages his daughter to follow in his footsteps, and the film is very broadly the story of her growth as an artist. It’s told in a series of anecdotes that flow one into another, revolving around various themes. O-Ei has various romantic or near-romantic interludes with young male pupils or rivals of Hokusai. She helps take care of her blind younger sister O-Nao, while Hokusai, terrified of death and illness, keeps O-Nao at a distance. Ghosts and dragons appear, not horrific but folkloric. Above all, O-Ei struggles with her art and with selling prints and with trying to become better. Like her father she tries drawing erotica — but the general consensus, at least among the men who see her work, is that while she’s extremely effective at drawing women, her males are copied from her father’s art. According to Hokusai, O-Ei won’t admit she hasn’t the experience needed to draw men.

The visual style is highly realistic, marrying seemingly hand-drawn animation and subtle 3D effects. Images return at key points: a bridge in Edo, a red flower. It’s not an obvious movie, with development hinted at obliquely over the whole story. It’s quiet, meditative, and demands the audience think about what they’re seeing. This works because the characters are so rich and vivid you naturally want to understand them, want to spend time considering their situations and problems.

And part of that in turn is because they’re in the middle of an intensely real setting. The Edo of two hundred years ago lives and breathes here. The film’s filled with subtle visual detail establishing place and culture. I don’t know much about the details of day-to-day life in Edo, but this film builds a fully-realised world (Wikipedia tells me that Sugiura, who died ten years ago, was known as an expert in the Edo period). The things of everyday life, cutlery and pipes and combs and pens, all have their distinct designs. Fashion, architecture, even things like firefighting techniques are all unobtrusively detailed. More than that, this is the sort of film that manages the trick of engaging more than sight and hearing — the visuals and sounds are so well-chosen as to evoke textures and smells, making the past tangible.

And what’s particularly interesting to me personally is the way in which this intensely realistic film incorporates the fantastic. There are ghosts and demons here, at the edge of reality — in dreams and visions, if nothing else, though at least one experience by a courtesan’s bedside seems quite matter-of-fact. These things play into the film’s overall themes almost casually, and help establish what the characters think of their world. It feels coherent, linking art and the supernatural in a non-romantic but still visionary way.

And what’s particularly interesting to me personally is the way in which this intensely realistic film incorporates the fantastic. There are ghosts and demons here, at the edge of reality — in dreams and visions, if nothing else, though at least one experience by a courtesan’s bedside seems quite matter-of-fact. These things play into the film’s overall themes almost casually, and help establish what the characters think of their world. It feels coherent, linking art and the supernatural in a non-romantic but still visionary way.

Miss Hokusai is a subtle, touching film about art and life and death and a new generation emerging. “Life is nothing special, but we’re enjoying it,” says one character near the end; but in fact the film makes life special. It finds beauty in the elements of what life is, whether two hundred years ago or today. There’s some tragedy in the film, and also a good deal of warmth. It kept me off-balance, as various incidents played out in ways I didn’t expect. And it pulled me in, encouraging me to work out what the connections were. Overall, it avoids obvious drama in favour of day-to-day life, and it makes that choice work.

After the film, Hara took questions from the audience. He revealed that it took him three years to make the movie. He observed that Hokusai really did have a daughter, who really was an artist herself, but that not much of her work has survived and little is known about her. He stressed the importance of the original manga to the film, and said that it was difficult to adapt as it was a series of short stories. Asked what his favourite scene was, he mentioned a death scene near the end. He discussed the soundtrack, noting that he had electric guitar on the soundtrack because in his view O-Ei was “rock and roll.” The last question came from an audience member who asked about the characters in the word Sarusuberi (the title of Sugiura’s manga; according to the IMDB the film’s original title is Sarusuberi: Miss Hokusai, and in English just Miss Hokusai). It refers to a flower that blooms for a hundred days — the crape myrtle — which is seen in the film; Hara said he thought of it as an image of Hokusai’s endless creativity.

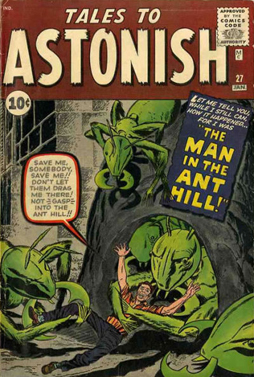

With that, the theatre was cleared, and I went out into the Hall lobby to wait in line for the next film, Ant-Man. A few minutes later I was back in almost the same seat, watching people file in. It seemed to me that the gender balance of the crowd was fairly even, much the same as for Miss Hokusai, but that the age was on the whole younger. At any rate, it would turn out to be a tremendously enthusiastic — and knowledgeable — audience. Sometimes you’re lucky enough to watch a movie alongside a packed house of people who really appreciate what they’re watching, and that was the case for me here. The crowd was thrilled with this movie from the start, breaking into mad applause any number of times. And not just at inventive action moves or clever one-lines. This was an audience that gave a loud cheer when the first rumours of Ant-Man’s existence were described as ‘tales to astonish’ (the title of the comic where the character debuted), and that went nuts at the inevitable cameo of Stan the Man. To say nothing of the various other large or small nods to the Marvel film universe and Marvel comics history. Frankly, purely in terms of crowd reaction, it was one of the most enjoyable experiences I’ve ever had in a movie theatre.

With that, the theatre was cleared, and I went out into the Hall lobby to wait in line for the next film, Ant-Man. A few minutes later I was back in almost the same seat, watching people file in. It seemed to me that the gender balance of the crowd was fairly even, much the same as for Miss Hokusai, but that the age was on the whole younger. At any rate, it would turn out to be a tremendously enthusiastic — and knowledgeable — audience. Sometimes you’re lucky enough to watch a movie alongside a packed house of people who really appreciate what they’re watching, and that was the case for me here. The crowd was thrilled with this movie from the start, breaking into mad applause any number of times. And not just at inventive action moves or clever one-lines. This was an audience that gave a loud cheer when the first rumours of Ant-Man’s existence were described as ‘tales to astonish’ (the title of the comic where the character debuted), and that went nuts at the inevitable cameo of Stan the Man. To say nothing of the various other large or small nods to the Marvel film universe and Marvel comics history. Frankly, purely in terms of crowd reaction, it was one of the most enjoyable experiences I’ve ever had in a movie theatre.

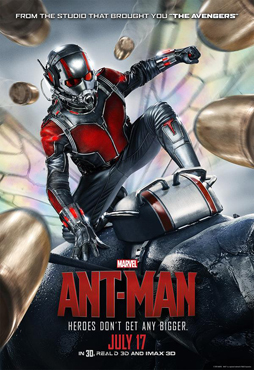

That said, the film was a blast on its own terms. I generally like the Marvel movies, but I was utterly unprepared for how inventive this one was. I wouldn’t have thought of Ant-Man as one of Marvel’s most visually spectacular characters, but the movie seems to draw inspiration from the early Jack Kirby stories. It’s almost always a good idea to go back to Kirby, and when he drew the “Ant-Man” short stories in Tales to Astonish he didn’t just draw ‘a tiny super-hero,’ he drew ‘a super-hero’ in a distorted, gigantic world that happens to be our own at a different scale. It’s a subtle distinction, but it makes the difference between a relatively underpowered character and a hero who takes on a strange world from his own distinct angle — someone surrounded by ogres and dangers and the tiny monsters all around us that we don’t notice. The movie runs with that, building an almost psychedelic feel into Ant-Man’s adventures.

Visually, it’s consistently spectacular. The fight scenes are incredibly well-staged, with characters (and camera) shifting sizes in mid-move. This was one of the few films I’ve ever seen where I thought 3D was used well throughout, in the standing-around-and-talking bits as well as the action bits. And it’s colourful, especially in the size-shifted scenes. In combination with its effective humour and quick but thoughtful pacing — it runs under two hours, positively brief for a super-hero movie these days — it all feels exuberant, an energy-drink of a movie.

Visually, it’s consistently spectacular. The fight scenes are incredibly well-staged, with characters (and camera) shifting sizes in mid-move. This was one of the few films I’ve ever seen where I thought 3D was used well throughout, in the standing-around-and-talking bits as well as the action bits. And it’s colourful, especially in the size-shifted scenes. In combination with its effective humour and quick but thoughtful pacing — it runs under two hours, positively brief for a super-hero movie these days — it all feels exuberant, an energy-drink of a movie.

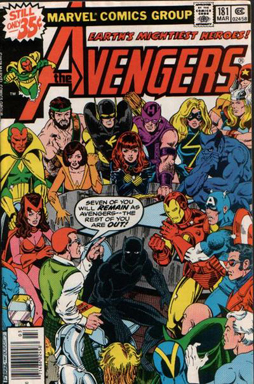

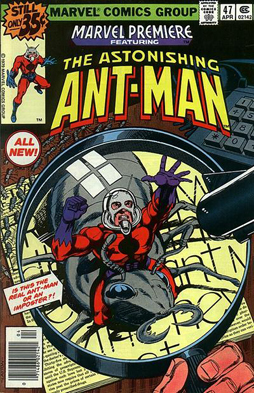

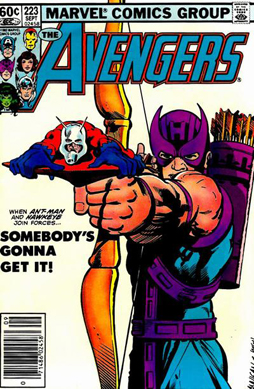

(Credits for the film get a bit complicated, though. Deep breath: Peyton Reed directed, likely working with concepts originated by Edgar Wright, who developed an Ant-Man film for years and retains a script credit along with his writing partner Joe Cornish. Wright left due to conflicts with Marvel, and Adam Mackay and star Paul Rudd then rewrote the script. The first Ant-Man comics story, the 7-page tale “The Man in the Ant Hill” in Tales to Astonish 27, was pencilled by Jack Kirby and inked by Dick Ayers, plotted by Stan Lee, and scripted by Larry Lieber, with colouring by Stan Goldberg. The character of Scott Lang was introduced in Avengers #181, written by David Michelinie and pencilled by John Byrne with finished art and inks by Gene Day and colours from Francoise Mouly [of all people]. The next month, Lang became Ant-Man in Marvel Premiere #47; script by Michelinie, breakdowns by Byrne, finished art by Bob Layton, and colours by Bob Sharen.)

The story of the film’s fairly simple. Scientist Hank Pym was the superhero called Ant-Man in the 1980s, a low-profile adventurer whose powers, to shrink to the size of a thumbnail and to command ants, naturally lent themselves to espionage. Now, his former protégé intends to sell on the open market a suit derived from Pym’s work but with more offensive weaponry. Pym has to stop him. Enter Scott Lang, a former burglar who’s just gotten out of prison. Lang, disgusted with corporate wrongdoing, stole from the rich to give back to the poor the rich originally stole from. Now he’s divorced, and his ex-wife won’t let him see his daughter, and he can’t get a job. Which all leads to Pym recruiting him as a super-hero. But why doesn’t Pym just turn to his daughter, Hope, who seems much more qualified?

The story of the film’s fairly simple. Scientist Hank Pym was the superhero called Ant-Man in the 1980s, a low-profile adventurer whose powers, to shrink to the size of a thumbnail and to command ants, naturally lent themselves to espionage. Now, his former protégé intends to sell on the open market a suit derived from Pym’s work but with more offensive weaponry. Pym has to stop him. Enter Scott Lang, a former burglar who’s just gotten out of prison. Lang, disgusted with corporate wrongdoing, stole from the rich to give back to the poor the rich originally stole from. Now he’s divorced, and his ex-wife won’t let him see his daughter, and he can’t get a job. Which all leads to Pym recruiting him as a super-hero. But why doesn’t Pym just turn to his daughter, Hope, who seems much more qualified?

We soon find out that there are reasons buried in Pym’s own past — strong character reasons, which have to do with the fate of Hope’s mother Jan. It’s interesting that this is a story in which the reason why a woman doesn’t get super-powers is literally because a cranky old white guy says she can’t, and the last of the first (of two) post-credit sequences seems to wink at this. But it also promises that things are about to change.

At any rate, in a lot of ways this film is a refining and advancing of the Marvel movie recipe. I avoid saying ‘formula’ because it doesn’t feel that mechanical, but you can see the familiar ingredients along with a couple new twists. If previous Marvel films have married the superhero story to other genres like fantasy (Thor) and monster movies (Hulk) and political thrillers (Captain America: The Winter Soldier), this is a superhero movie as heist film. It’s about more than the heist, as the characters say, but it brings the Marvel brand of action and humour and wraps it around the story of a theft, with schemes and plans and double-crosses and last-second computer hacking and montages of men at work.

At the same time, it plays with the universe that’s already been built up. It takes full advantage of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, by which I mean it doesn’t just bring in bits and pieces from other movies but uses them to expand its own theme. It’s not just that Hank Pym’s heard of the spy agency SHIELD, but he has an opinion about them informed by who he is. Characters debate turning the whole problem over to the Avengers. And, maybe most importantly, we’ve reached the point where superheroes are taken for granted as a part of the world. Ant-Man’s a superhero, and that’s just what he is, no explanation for his costume or code-name needed.

At the same time, it plays with the universe that’s already been built up. It takes full advantage of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, by which I mean it doesn’t just bring in bits and pieces from other movies but uses them to expand its own theme. It’s not just that Hank Pym’s heard of the spy agency SHIELD, but he has an opinion about them informed by who he is. Characters debate turning the whole problem over to the Avengers. And, maybe most importantly, we’ve reached the point where superheroes are taken for granted as a part of the world. Ant-Man’s a superhero, and that’s just what he is, no explanation for his costume or code-name needed.

That’s part of the reason why this feels more like a classic Marvel comic than almost any of the other films. Enough has been established that you can see the comics’ storytelling moves beginning to transfer over to film. Two heroes fight due to a misunderstanding? Yeah, we get a part of that, thanks to an extended cameo from another Marvel character. A villain sells his evil super-weapon, and the same guys show up to buy it as always show up to buy evil super-weapons in Marvel comics. And, near the end, there’s a moment of the kind of cosmic weirdness that some of the best Marvel books have but which have been missing from the movies so far: a visually startling sequence that both fits into the film and yet feels larger than its plot significance.

The visuals, of course, would mean nothing without credible performances anchoring them. And the cast does good work here. Michael Douglas plays Hank Pym as nerdy but dangerous, appropriately bug-eyed with anger but always a step ahead in his plans. Evangeline Lilly’s Hope van Dyne has inherited his anger, but restrains it under an icy exterior. Corey Stoll as Darren Cross, the villain of the piece, plays his character a little far over the edge for my taste but does make for one of Marvel’s more effective antagonists.

Still, the movie’s largely carried by Paul Rudd. I’ll cop at this point to having always liked Scott Lang as a character, though I was never really sure why — he’s just one of those characters I liked seeing whenever he happened to turn up. Rudd and this movie go a along way to explaining what’s interesting about him: he’s a mix of competency and limitations. He’s not a genius, but he is a guy who’s smart and good at what he does, and an early moment showing him improvising a MacGyver-esque way through a locked door goes some distance to establishing his intelligence. Maybe most importantly, Lang’s a single father who doesn’t just love his daughter but actively has a sense of responsibility toward her that informs his actions.

Still, the movie’s largely carried by Paul Rudd. I’ll cop at this point to having always liked Scott Lang as a character, though I was never really sure why — he’s just one of those characters I liked seeing whenever he happened to turn up. Rudd and this movie go a along way to explaining what’s interesting about him: he’s a mix of competency and limitations. He’s not a genius, but he is a guy who’s smart and good at what he does, and an early moment showing him improvising a MacGyver-esque way through a locked door goes some distance to establishing his intelligence. Maybe most importantly, Lang’s a single father who doesn’t just love his daughter but actively has a sense of responsibility toward her that informs his actions.

Most Marvel heroes up to this point have been fairly distinct from one another, and while you’d think a good-guy thief would be close to Chris Pratt’s Star-Lord from Guardians of the Galaxy, the two are very different. Rudd’s Lang is more introverted, more thoughtful, and older. He’s been through more, he’s a father, he relates to women in an adult way. He’s more idealistic, and he’s paid a price for his ideals. And while he doesn’t abhor violence — he is a superhero — he does dislike it.

Interestingly, the motif of Lang and Cross as rival ‘sons’ for Hank Pym is relatively underplayed. This is much more a film about fathers and daughters, contrasting Hank’s relationship with Hope against Scott’s with his young daughter Cassie (ably played by young Abby Ryder Fortson, who I suppose I can look forward to taking up the role of Stature in Marvel Phase Six or thereabouts). It gives the movie an emotional centre; among other things, Pym’s smart enough to use his alienation from his own daughter to motivate Scott with a kind of cautionary example. But it doesn’t stop there, as the relationships between the characters in this film continually develop.

Are there flaws in the movie? Sure, there always are. I thought the knockabout humour of Scott’s multiethnic support gang was overly broad, to say the least. I thought Cross was underwritten as a character. Certain plot points were obvious. And I can understand the reaction of people who feel that the basic story of the superhero movie is getting tired. I enjoy the things, and I could cheerfully do without ever seeing another one where the villain is a larger and meaner version of the hero.

Are there flaws in the movie? Sure, there always are. I thought the knockabout humour of Scott’s multiethnic support gang was overly broad, to say the least. I thought Cross was underwritten as a character. Certain plot points were obvious. And I can understand the reaction of people who feel that the basic story of the superhero movie is getting tired. I enjoy the things, and I could cheerfully do without ever seeing another one where the villain is a larger and meaner version of the hero.

Still, for me Ant-Man brings enough novelty to the table, enough sheer invention, to more than justify its existence. The final fight may be one of the most visually inventive superhero battles ever put on screen — not the biggest, obviously, probably not the most special-effects intensive and certainly not the most violent, but the cleverest in the use of the combatants’ powers and in finding striking images. Overall, there’s a sustained sense throughout the film of what I can only call joy. By which I do not mean that everybody’s happy all the time. Only there’s a lightness of spirit about it. You can’t help but notice the contrast with the developing DC film universe in a week when Time-Warner released two separate dour trailers for their own upcoming films.

A bit under a year ago I saw Guardians of the Galaxy at Fantasia, again with an enthusiastic audience; I liked it, but felt it was missing something, an element of the cosmic zap of the original comics. Weirdly, that cosmic zap’s here in Ant-Man, of all places. Maybe this film can get away with that because it’s otherwise relatively grounded in reality. At any rate, it all makes for a strong movie. I liked Guardians, but I like this one more. To be fair, some of that may be my familiarity with the source material. Guardians brought across a goodly amount of what I liked about the original comics, but left some stuff out. Ant-Man exceeded my expectations wildly. Bright and filled with almost old-fashioned banter, it may be the best Ant-Man story anybody’s ever told — or, at least, the best since the days of Kirby. I don’t normally come out of movies hoping for sequels, but I have to admit I’d like to see more of these characters fighting crime together.

(The second instalment of my Fantasia Diary for this year, covering the French thriller Un homme idéal, the martial-arts action movie Kung Fu Killer, and the Japanese comedy-drama Wonderful World End, is here. The next instalment, looking at the Austrian horror-comedy Therapy for a Vampire, the Welsh-set Danish teen drama Bridgend, the Japanese sf comedy Assassination Classroom, the Indian horror movie Ludo, and Who Killed Captain Alex?: Uganda’s First Action Movie, is here. Here I look at the Chinese fantasy-sf epic Teana: 10000 Years Later, the Korean post-apocalypse animated film Crimson Whale, and the Danish high fantasy The Shamer’s Daughter). Here are reviews of the puppet wuxia movie The Arti: The Adventure Begins, the metafictional Director’s Commentary: Terror of Frankenstein, the politically charged documentary (T)ERROR, and I Am Thor, a documentary about longtime heavy metal road warrior. I discuss Fantasia’s International Science Fiction Short Film Showcase, and the psychodrama Meathead Goes Hog Wild, here. Here I look at a re-release of the Shaw Brothers’ kung-fu special effects classic Buddha’s Palm, the Nigerian zombie movie Ojuju, the British-Canadian horror-suspense classic The Reflecting Skin, and the quirky Japanese romantic comedy Haruko’s Paranormal Laboratory. A few thoughts about the documentary Raiders!: The Story of the Greatest Fan Film Ever Made, the drama-comedy-boxing-movie 100 Yen Love, and the historical fashion epic The Royal Tailor may be found here.

Here I look at the bleak Korean animated science-fiction film On the White Planet and the Thai gay romance ghost story The Blue Hour. I review Mamoru Oshii’s surreal live-action movie Nowhere Girl, and Princess Jellyfish, a romantic comedy about otaku, here. The documentary Monty Python: The Meaning of Live and the Henry Rollins noir-horror-comedy He Never Died are discussed here. Here I look at The Visit, a documentary about how governments and scientists would react to an alien landing, and The Demolisher, a suspense vigilante thriller that homages giallo film. Here are reflections on the wordless animated comedy Minuscule, the horror-suspense film Observance, the YA action film Boy 7, and the action-comedy Big Match. I look at the science-fiction film Synchronicity, the horror film The Dark Below, the black comedy Traders, and a showcase of the work of fantasy film grandmaster Georges Méliès here.

Here I look at the horror-comedy (or urban fantasy) Ava’s Possessions, the Indonesian wuxia movie The Golden Cane Warrior, the surreal science-fictional H., and the post-apocalyptic comedy Turbo Kid. Discussions of the fantasy blockbuster epic Snow Girl and the Dark Crystal, the documentary Remix, Remake, Ripoff: About Copy Culture and Turkish Pop Cinema, the mythic post-apocalypse fable Orion, and the social media–themed drama Socialphobia are here. Here I look at the antimated version of Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, the Outer Limits of Animation 2015 Showcase, the Stanley Milgram biopic Experimenter, the historical fantasy-thriller Ninja the Monster, and the Japanese super-hero movie Strayer’s Chronicle. The Ethiopian post-apocalypse quest movie Crumbs, the Spanish crime movie Marshland, the American thriller The Invitation, and the French philosophical science-fiction comedy Cosmodrama are discussed here. I write about my last day at Fantasia here, discussing Rurouni Kenshin: The Legend Ends — third in a series of samurai movies — as well as the Korean period espionage-action movie Assassination, and Part 1 of the live-action Attack on Titan. I write about six more movies here (the romantic comedy Poison Berry in my Brain, the biting satire Anima State, and the psychological thriller The Interior) and here (the horror-inflected drama They Look Like People, the horror-comedy Nina Forever, and the exultantly straight-ahead horror movie Hostile). And I have a few final thoughts here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.