Fantasia Diary 2015, Day 19: Snow Girl and the Dark Crystal; Remix, Remake, Ripoff: About Copy Culture and Turkish Pop Cinema; Orion; and Socialphobia

Saturday, August 1, would start early for me at Fantasia. At 12:30 I was seeing a Chinese fantasy adventure called Snow Girl and the Dark Crystal. Then I’d head over to the screening room, where I planned to watch a documentary about the Turkish film industry, Remix, Remake, Ripoff: About Copy Culture and Turkish Pop Cinema. Then I’d go to the De Sève Theatre for a pair of films, the post-apocalypse art-house movie Orion and then the Korean drama Socialphobia. Once again, a nice varied day.

Saturday, August 1, would start early for me at Fantasia. At 12:30 I was seeing a Chinese fantasy adventure called Snow Girl and the Dark Crystal. Then I’d head over to the screening room, where I planned to watch a documentary about the Turkish film industry, Remix, Remake, Ripoff: About Copy Culture and Turkish Pop Cinema. Then I’d go to the De Sève Theatre for a pair of films, the post-apocalypse art-house movie Orion and then the Korean drama Socialphobia. Once again, a nice varied day.

Snow Girl and the Dark Crystal (Zhong Kui fu mo: Xue yao mo ling) is a blockbuster loosely based on Chinese myth, directed by Peter Pau and Zhao Tianyu with a script by Zhao, Qin Zhen, Shen Shiqi, Li Jie, Raymond Lei Jin, and Eric Zhang. It opens quickly, with the gods trying to save the city of Hu from the forces of hell. One god, Zhang Daoxian (Winston Chao) offers to send his pupil, Zhong Kui (Kun Chen) into hell to steal a crystal vital to the demons’ scheme. Zhong succeeds and takes the crystal to Hu; Zhang teaches him further magical demon-slaying tricks as the demons scheme to get the crystal back. A caravan of entertainers soon come to Hu featuring the lovely Snow Girl (Li Bingbing) — in reality a demon who shares a past with Zhong. But Zhong’s now gained a magical sword, and an alternate shape as a ten-foot-tall spider-giant. He needs all his new might to turn back the forces of hell, but more is going on than meets the eye.

The plot unfolds nicely, complex and full of twists without being too frantic. The story seems to me to be relatively accessible to people used to Western structures. It’s got a few thoughts about love and society and hypocrisy, but nothing especially elaborate — this is solid big-budget epic filmmaking, with bright visuals and lots of action and heroes and villains. As such, it succeeds.

The movie’s filled with CGI, to the point where it sometimes seems more like animation than live-action. Much of the graphics work is beautiful, particularly the backgrounds and the character design. Some of the actual shots seem to fall into the trap of ignoring physics a bit too much, and the sheer amount of imagery does occasionally impart a video-game feel to the movie. That’s oddly not an entirely bad thing. The feel of the effects, the style of the graphics, is consistent — and as a result the unreal feeling of the CGI helps to build a world. This is what myth looks ike. This is what magic looks like. You can’t imagine a ten-foot-tall spider-giant is going to look or move like anything you’ve ever seen in real life.

The movie’s filled with CGI, to the point where it sometimes seems more like animation than live-action. Much of the graphics work is beautiful, particularly the backgrounds and the character design. Some of the actual shots seem to fall into the trap of ignoring physics a bit too much, and the sheer amount of imagery does occasionally impart a video-game feel to the movie. That’s oddly not an entirely bad thing. The feel of the effects, the style of the graphics, is consistent — and as a result the unreal feeling of the CGI helps to build a world. This is what myth looks ike. This is what magic looks like. You can’t imagine a ten-foot-tall spider-giant is going to look or move like anything you’ve ever seen in real life.

And the mythic sense of the movie is generally its strong point, showing us heaven and hell, the court of the Jade Emperor and shapeshifting demons and a magic duel and a brave guardian qilin and on and on. The movie never wastes time on needless exposition, but all these things feel like natural parts of the same world. And that world’s built up efficiently, to just exactly the extent it needs to be. At one point there’s a mention of the Tang dynasty, giving a loose era for the film, but there’s no period-specific politics; this is all legend and adventure. What you need to know about the setting, in terms of culture or geography or technology, is all there onscreen and all communicated swiftly and effectively.

The story we get is operatic. It’s filled with violence, with Zhong fighting demons and going to hell and defending Hu against a demonic siege. But the love affair with Snow Girl gives the movie its heart. Sometimes things slow down, as flashbacks fill in details of how they met. But then the love affair also builds to some of the movie’s most visually stunning moments, particularly a scene late in the film where Snow Girl has to calm a berserk Zhong. The CGI is at its most unrealistic here, but that’s my point: it heightens the unreality, the sense of powers beyond human.

There are times where the emotions and character beats seem too cartoony, too exaggerated, and at those times the stylised CGI doesn’t help. But if you think of this movie as a filmed comic book — not necessarily a super-hero comic, but a bright fast-paced adventure-for-a-dime — then it comes together. In fact there are some distant tonal similarities to Jack Kirby’s Thor comics, as Zhong transforms from a human shape into a mythic hero to fight the forces of evil. It’s an interesting image, given Zhong’s generally concerned with his role in life and whether it’s possible for him to change from being the demon hunter he thinks he is. Add it all up, and it’s an entertaining movie that occasionally overplays its hand but moves quickly and gets the job done.

There are times where the emotions and character beats seem too cartoony, too exaggerated, and at those times the stylised CGI doesn’t help. But if you think of this movie as a filmed comic book — not necessarily a super-hero comic, but a bright fast-paced adventure-for-a-dime — then it comes together. In fact there are some distant tonal similarities to Jack Kirby’s Thor comics, as Zhong transforms from a human shape into a mythic hero to fight the forces of evil. It’s an interesting image, given Zhong’s generally concerned with his role in life and whether it’s possible for him to change from being the demon hunter he thinks he is. Add it all up, and it’s an entertaining movie that occasionally overplays its hand but moves quickly and gets the job done.

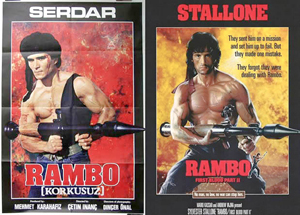

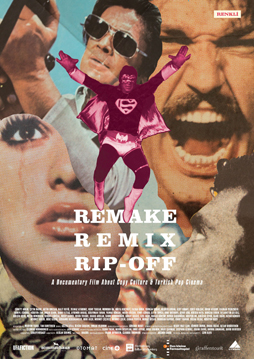

Next up was Remix, Remake, Ripoff: About Copy Culture and Turkish Pop Cinema (or Motör: Kopya Kültürü ve Popüler Türk Sinemasi). From the 1940s through the 1980s, and especially in the 60s and early 70s, the Turkish film industry was churning out a massive number of films to meet an extensive domestic demand — sometimes hundreds of films per year, written by as few as three writers. The industry had no time to labour over a film, and no resources to put into making them look good; sometimes even getting ahold of the film to shoot on was a struggle. But by a variety of techniques, the Yesilçam industry (named for the street where it was centred) managed to meet demand. Some of the films, unauthorised remakes of American originals, have become notorious. Remix, Remake, Ripoff explains the story behind them, and it’s a fascinating piece of cinema history.

It’s a German-Turkish co-production — the film explains that at one point tapes of Yesilçam films were dumped in German video stores, so for a time renting Turkish films was not uncommon in Germany. Written and directed by Cem Kaya, it seems to speak with anyone who was anyone in the Turkish industry during its glory days. It’s an extensive, thorough, and very info-dense documentary.

We learn about the elaborate movie palaces of Turkey, which could (and usually did) hold an audience of 2000 people. About the regional demands for film that pushed Yesilçam’s production. About a man who directed 200 films, about actors who played in over a thousand films, about a man who’d been in so many movies that if the physical film of all of them had been spliced together it would circle the Earth — twice. We get some cynical sidelights on the industry, how melodramas were preferred by the government, whoever was in power: “All governments liked melodramas. The people should cry and then feel relief.” Educated people didn’t go to these films, or if they did, they kept it secret from their friends. On the other hand, women and families were important segments of the audience.

We learn about the elaborate movie palaces of Turkey, which could (and usually did) hold an audience of 2000 people. About the regional demands for film that pushed Yesilçam’s production. About a man who directed 200 films, about actors who played in over a thousand films, about a man who’d been in so many movies that if the physical film of all of them had been spliced together it would circle the Earth — twice. We get some cynical sidelights on the industry, how melodramas were preferred by the government, whoever was in power: “All governments liked melodramas. The people should cry and then feel relief.” Educated people didn’t go to these films, or if they did, they kept it secret from their friends. On the other hand, women and families were important segments of the audience.

Stories were stolen from every available source. Storytelling elements were recycled frantically. Patterns stayed the same. Bloody handkerchiefs. Doctors giving bad news. Blindness. Amnesia. Revelations of unsuspected sons and daughters. It seems to have had a soap opera feel, but with fights: “A film had to have at least six brawls.” Anything good was copied, including foreign films, since Turkey did not acknowledge international copyright.

This led to the Turkish remakes so well-known on the internet. Yesilçam remade everything from Some Like it Hot (itself based on a German remake of a French film) to A Fistful of Dollars. Music was swiped: a film-maker shows his library of soundtrack records, literally records of other films’ soundtracks. Emanuelle for love scenes. The Pink Panther for comedy.

This led to the Turkish remakes so well-known on the internet. Yesilçam remade everything from Some Like it Hot (itself based on a German remake of a French film) to A Fistful of Dollars. Music was swiped: a film-maker shows his library of soundtrack records, literally records of other films’ soundtracks. Emanuelle for love scenes. The Pink Panther for comedy.

There are stories about making the films: how national quotas limiting the import of film was de facto censorship, leading to film being smuggled like drugs (a potent simile if I’ve ever heard one). Every part of filmmaking’s covered in the documentary, examining writing and directing and acting — actors who were responsible for maintaining their own character’s continuity from shot to shot, actors who had no stunt doubles, actors who broke bones and kept going. Improvised special effects. Dolly tracks for the cameras built out of scrap and tables broken up for the purpose. An actor reflects: “Yesilçam always found a way. No matter what. The people were unqualified, but they were smart.” Another filmmaker says, more bleakly, “How to keep your kids warm without an oven? You think of something.”

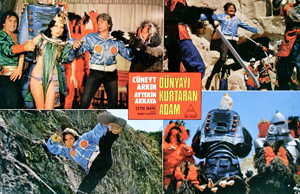

This leads to The Man Who Saved the World (Dünyayi Kurtaran Adam), sometimes called “Turkish Star Wars.” It was directed by Çetin Inanç, who stole a print of Star Wars — bribing a guard to do it — and cut it together with some original footage and a number of other movies; nineteen films have been identified in it, with eight separate films providing music for the soundtrack. One actor calls Inanç a “film magician.” The documentary argues that Çetin Inanç created an individual thing out the collage of movies he used, leading to critics discussing the nature of Turkey’s relationship to the West and how that shaped film culture.

This leads to The Man Who Saved the World (Dünyayi Kurtaran Adam), sometimes called “Turkish Star Wars.” It was directed by Çetin Inanç, who stole a print of Star Wars — bribing a guard to do it — and cut it together with some original footage and a number of other movies; nineteen films have been identified in it, with eight separate films providing music for the soundtrack. One actor calls Inanç a “film magician.” The documentary argues that Çetin Inanç created an individual thing out the collage of movies he used, leading to critics discussing the nature of Turkey’s relationship to the West and how that shaped film culture.

I frankly would have liked more discussion of this point. One critic mentions an “adaptation culture” and talks about the re-editing of a movie as “a way to make it Turkish, because the very reason of its existence is its ‘other,’ the West.” It’s a fascinating point that I thought could have been expanded on and further contextualised. What does it mean to make a new movie out of an existing movie? What do the changes say, and what do they mean? I was frankly expecting more investigation of these questions than the movie actually presents. That said, it’s hard to see what could have been cut. It’s touching to see Çetin Inanç reflecting on the fame his version of Star Wars has found, and on being invited to speak at Columbia University because of his work.

Remix, Remake, Ripoff gives a typically clear and detailed picture of the demise of the classic Turkich film industry as well. Censorship became a problem after a military coup — oddly, the censors didn’t care if Yesilçam shot porn films, but clamped down on the melodramas previous administrations found useful. There’s a description of the current Turkish TV industry, which seems to be the heir to Yesilçam in the way it produces vast amount of material on tight budgets and tighter schedules. By the end of the film, the depiction of the demolition of a classic Turkish movie palace is genuinely affecting; you understand there’s a heritage behind it, that it was a place where thousands of people found meaning.

Remix, Remake, Ripoff gives a typically clear and detailed picture of the demise of the classic Turkich film industry as well. Censorship became a problem after a military coup — oddly, the censors didn’t care if Yesilçam shot porn films, but clamped down on the melodramas previous administrations found useful. There’s a description of the current Turkish TV industry, which seems to be the heir to Yesilçam in the way it produces vast amount of material on tight budgets and tighter schedules. By the end of the film, the depiction of the demolition of a classic Turkish movie palace is genuinely affecting; you understand there’s a heritage behind it, that it was a place where thousands of people found meaning.

Remix, Remake, Ripoff does what a good documentary has to do: entertains and educates at once. You come away from it not just understanding the subject, but touched by it. It’s filled with great stories and some sharp reflections on the necessities underlying filmmaking, then and now. It’s an excellent movie about movies and about the pull movies have.

After which, I went back to the De Sève for the world premiere of writer/director Asiel Norton’s film Orion. Norton introduced the film briefly, reflecting: “It was a very long process, with very little money.”

A century after the collapse of civilization, a pregnant virgin (Lily Cole) is held prisoner by a strange magician (Goran Kostic). The child is born, and changed into a tree. A hunter (David Arquette) comes to their home, in some abandoned city. The Hunter and the Magus play a game of cards. And the Hunter decides to rescue the Virgin, and take her with him into the north. Things do not go entirely according to plan.

I’ve had a lot of time to think about Orion by this point, and I’m still not sure what I think about it. I’ve spoken with people who greatly appreciated it and others who dismissed it. I can see both sides. There’s a certain affectedness to the film, and an obvious attempt to create a myth. There seem to be elements recalling the Greek myths about Orion, but so far as I can see those myths themselves are fragmentary and contradictory. There are also strong remembrances of Christianity, which I’m not sure helps the film’s syncretic approach — the Christian elements risk drowning out the touches of other stories.

I’ve had a lot of time to think about Orion by this point, and I’m still not sure what I think about it. I’ve spoken with people who greatly appreciated it and others who dismissed it. I can see both sides. There’s a certain affectedness to the film, and an obvious attempt to create a myth. There seem to be elements recalling the Greek myths about Orion, but so far as I can see those myths themselves are fragmentary and contradictory. There are also strong remembrances of Christianity, which I’m not sure helps the film’s syncretic approach — the Christian elements risk drowning out the touches of other stories.

Broadly, I think the movie’s about rebirth. I think it perhaps has to do with the idea of a ritual sacrifice. But I’m not sure. There’s a song the Virgin Mother sings in the middle of the film that might hold a hint — but I couldn’t make out the lyrics for the life of me.

Visually, the movie’s often disorienting, with images out of focus, the camera moving. And yet I found at the end that it had a distinctive sense of an abandoned world. I think the stylised camerawork helps that; the lack of focus makes you think the world itself is muddled, misty, lacking in certainty and straight edges. The visual compositions intrigue me, at least, even when the literal communication of narrative is unclear. Oddly, it all seems to serve to build the world. I don’t know that Orion creates the best post-apocalyptic world that I saw at Fantasia, but it may have done the most with the least resources.

Visually, the movie’s often disorienting, with images out of focus, the camera moving. And yet I found at the end that it had a distinctive sense of an abandoned world. I think the stylised camerawork helps that; the lack of focus makes you think the world itself is muddled, misty, lacking in certainty and straight edges. The visual compositions intrigue me, at least, even when the literal communication of narrative is unclear. Oddly, it all seems to serve to build the world. I don’t know that Orion creates the best post-apocalyptic world that I saw at Fantasia, but it may have done the most with the least resources.

The plot is fairly simple, but the details are ambiguous. The Magus may be a shape-shifter. A female figure the Hunter meets may be a trickster or may be just another victim: she is a Fool (I believe played by Maren Lord, though the lack of specific names make it difficult to work out from the IMDB’s cast list). Dialogue is terse and often confusing. There’s certainly a sense of archetypes at play, but to what end is uncertain. Perhaps with the aim of creating something new.

There’s nothing obvious here at all. If this is a new myth, it echoes older ones but has a plot completely different. Or does it? A cynic would say this is a movie where a virile younger man pits himself against a more intelligent and older man for the sake of a woman, and incidentally sleeps with another woman in the process (the women are shown topless, the men not shown nude). Which is all fairly generic. It’s hard not to notice, but doesn’t feel as though it entirely undercuts what’s happening onscreen.

There’s nothing obvious here at all. If this is a new myth, it echoes older ones but has a plot completely different. Or does it? A cynic would say this is a movie where a virile younger man pits himself against a more intelligent and older man for the sake of a woman, and incidentally sleeps with another woman in the process (the women are shown topless, the men not shown nude). Which is all fairly generic. It’s hard not to notice, but doesn’t feel as though it entirely undercuts what’s happening onscreen.

The riddles in this film feel like they have answers. As I’ve said, when I don’t understand a movie on one viewing, I ask myself: do I want to see it again? Do I believe a second viewing would clarify things, and is the sensory experience something I want to go through? The answer to those questions here is yes, I would see it again, and I do believe Norton has put enough in the movie to work out its meaning.

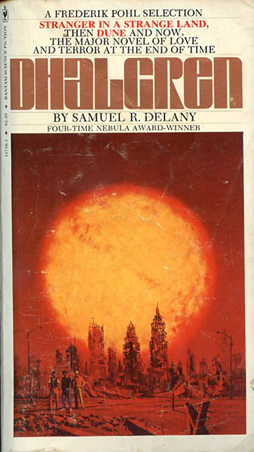

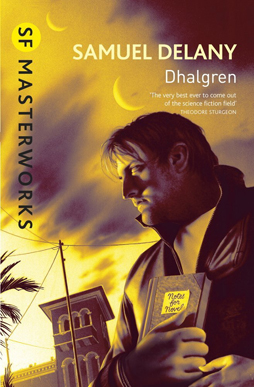

The feel of archetypes enacting myth reaches me. There’s a feeling almost of New Wave science fiction, of a formally ambitious story that may take more than one go-through to grasp. I’m hesitant to say it, but the story this film most calls to my mind is Delany’s Dhalgren — not that it’s really like Dhalgren at all, but that there’s something in its tone and ambition that’s closer to Delany than it is to anything else I can think of. Something in the way the film treats urban space, perhaps. Or perhaps it’s simply that the reddish tones of the film suggest that it takes place in a wounded autumnal city.

The feel of archetypes enacting myth reaches me. There’s a feeling almost of New Wave science fiction, of a formally ambitious story that may take more than one go-through to grasp. I’m hesitant to say it, but the story this film most calls to my mind is Delany’s Dhalgren — not that it’s really like Dhalgren at all, but that there’s something in its tone and ambition that’s closer to Delany than it is to anything else I can think of. Something in the way the film treats urban space, perhaps. Or perhaps it’s simply that the reddish tones of the film suggest that it takes place in a wounded autumnal city.

I suppose I have to say that the film succeeds, in that I think there’s enough in it to create a sense of myth and encourage me to watch it again. But I can’t really argue with people who think otherwise. In fact, even halfway through watching it I thought it was failing. What changed? I’m not sure. There are some dialogues between the Hunter and the Virgin Mother that add meaning, but I don’t think that was it. Possibly I adapted to whatever the movie was trying to do. Or maybe I began overthinking it. I will say that some of the individual scenes are potent images — the game of cards between the Hunter and the Magus, the Hunter being tortured, a chase and battle, shots of starry night given meaning by the constellation that dominates them. I would like to see it all being discussed more, and would like to see it again, to try to locate myself in this uncertain future world.

I suppose I have to say that the film succeeds, in that I think there’s enough in it to create a sense of myth and encourage me to watch it again. But I can’t really argue with people who think otherwise. In fact, even halfway through watching it I thought it was failing. What changed? I’m not sure. There are some dialogues between the Hunter and the Virgin Mother that add meaning, but I don’t think that was it. Possibly I adapted to whatever the movie was trying to do. Or maybe I began overthinking it. I will say that some of the individual scenes are potent images — the game of cards between the Hunter and the Magus, the Hunter being tortured, a chase and battle, shots of starry night given meaning by the constellation that dominates them. I would like to see it all being discussed more, and would like to see it again, to try to locate myself in this uncertain future world.

The question-and-answer period with Norton after the film was interesting. Asked where he shot it, he said that it was shot in Detroit, and said that being in some of the locations made him feel he was like standing in the ruins of his own civilization. He also mentioned his choice of location came about in part from trying to find things other people hadn’t shot. Asked about the inspiration for the film, Norton said that ideas come to him in images, and in this case the first image was the Hunter playing cards with a shamanistic figure who might be death (put like that it sounds similar to The Seventh Seal, but the way it plays out on screen suggests Norton always had something else in mind). He specifically envisioned a ‘shamanistic’ deck of cards like the Tarot, but not actually Tarot cards. He worked backward from that central image, writing notes, and when he had enough notes — and other images suggested by the notes — he put together a script.

Asked why he used the myth of Orion, Norton said that he wanted to convey the idea that after civilization collapsed, new myths would be created. If you look at the night sky and the stars, he said, Orion is the most prominent constellation, and therefore a likely inspiration for myth. Asked what an audience should take from the film, Norton said to take what you like. He said he had a simple idea, that he knew what he wanted to do, that he wanted to challenge the audience and let audiences work out what it means for themselves. That it should make sense for people in their own way, and that it should lend itself to being seen multiple times.

Asked whether the shooting of the film was spread out, Norton said it took a month to shoot. But it took years to complete around that, what with developing the idea and finding the cast and having a camera stolen; post-production in particular took a long time to get visual effects done on a low budget. Norton said everybody went through hell in making the movie; an actor onstage with him, the Fool, talked about the cold of Detroit in winter. Someone asked a follow-up about the visual effects, done in Serbia, and what Norton’s experience of working with the Serbians was like. Norton said he liked going to Serbia, that it was a cost-saving idea that took more time, but that everyone involved was kind. One of the movie’s producers (whose name I did not catch) mentioned that it was more complicated arranging for delivery of the shots across time zones and languages, but that it did result in a small savings.

Asked whether the shooting of the film was spread out, Norton said it took a month to shoot. But it took years to complete around that, what with developing the idea and finding the cast and having a camera stolen; post-production in particular took a long time to get visual effects done on a low budget. Norton said everybody went through hell in making the movie; an actor onstage with him, the Fool, talked about the cold of Detroit in winter. Someone asked a follow-up about the visual effects, done in Serbia, and what Norton’s experience of working with the Serbians was like. Norton said he liked going to Serbia, that it was a cost-saving idea that took more time, but that everyone involved was kind. One of the movie’s producers (whose name I did not catch) mentioned that it was more complicated arranging for delivery of the shots across time zones and languages, but that it did result in a small savings.

Asked about the photography, Norton said that the director of photography (Lyn Moncrief) got what he wanted. Norton said he made no conscious attempt to be unique in the way he shot, just did what he does; he’s interested in painting and visual art, and was concerned with trying to reach his original idea, letting that inform all his decisions. Asked specifically about the focus, Norton mentioned creating a concept of what he wanted to do before shooting. Asked how the movie was pitched to the producers, the producer spoke about knowing Norton from film school, and trusting his abilities.

That ended the question-and-answer period. Next up was Socialphobia, but before it screened there was a showing of a short film my notes say was called “Cassandre.” I can find no mention of it on the Fantasia web site or the IMDB, which means I very likely have the title wrong. It was in French with no subtitles; as I understand it, it had to do with a woman and a man and sexual power games that are not necessarily as they appear. It was effectively disturbing in an understated way, inflecting the sound of a social-media notification with emotion.

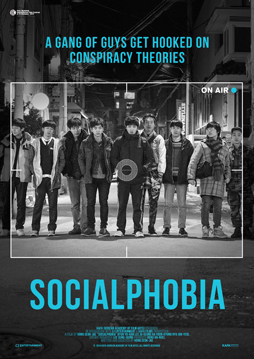

Socialphobia (So-syeol-po-bi-a) was written and directed by Hong Seok-jae. It’s a story about a group of young men, most prominently two aspiring police officers named Ji-weong (Byun Yo-han) and Yong-min (Lee Ju-seung), who gather when a young woman on social media has an unpopular opinion. In this case, the woman, who we later find is named Min Ha-yeong (Ha Yoon-kyeong), has sent a tweet cheering a soldier taking his own life. That sparks a general outrage on Twitter, and Ji-weong and Yong-min join a small group of men who figure out where Min lives and decide to confront her at her home. When they get there they find something they didn’t expect: Min’s hung herself. Since the small group of men had been tweeting and broadcasting their approach, it’s a reasonable assumption that they helped drive her to suicide. Except Yong-min doesn’t believe it, and enlists Ji-weong and the others in a quest to vindicate themselves.

Socialphobia (So-syeol-po-bi-a) was written and directed by Hong Seok-jae. It’s a story about a group of young men, most prominently two aspiring police officers named Ji-weong (Byun Yo-han) and Yong-min (Lee Ju-seung), who gather when a young woman on social media has an unpopular opinion. In this case, the woman, who we later find is named Min Ha-yeong (Ha Yoon-kyeong), has sent a tweet cheering a soldier taking his own life. That sparks a general outrage on Twitter, and Ji-weong and Yong-min join a small group of men who figure out where Min lives and decide to confront her at her home. When they get there they find something they didn’t expect: Min’s hung herself. Since the small group of men had been tweeting and broadcasting their approach, it’s a reasonable assumption that they helped drive her to suicide. Except Yong-min doesn’t believe it, and enlists Ji-weong and the others in a quest to vindicate themselves.

There are some awfully powerful ideas in this film, and some very provocative plot points. And yet they don’t quite pay off as well as they ought to. There’s something about the movie that stubbornly refuses to be as moving or disturbing as it could be. It’s a bit too pat, a bit too plot-heavy.

The investigation of Min’s death is full of twists. To an extent this makes sense — all sorts of questions are raised about identity on the internet, and about conspiracies. But at a certain point the thematic power’s lost in a mystery story that doesn’t seem structured to work with the subtext the movie’s trying to set up. The emotional beats aren’t investigated the way the whodunnit is. So although the movie’s clever, it’s not as profound as it could be.

Visually it’s solid, with lots of close-ups emphasising the bond that develops between Ji-weong and Yong-min. Min’s death is a scandal, and the two of them, along with the rest of their ad hoc mob, become pariahs. It’s literally them against the world. The movie represents that visually well enough, showing tweets onscreen deftly, if not brilliantly. You become aware as you watch that film’s an old medium, dating back to the century before last, and here it’s stretching out to try to deal with much newer media. Like listening to a radio drama about TV, or reading a book about film.

Visually it’s solid, with lots of close-ups emphasising the bond that develops between Ji-weong and Yong-min. Min’s death is a scandal, and the two of them, along with the rest of their ad hoc mob, become pariahs. It’s literally them against the world. The movie represents that visually well enough, showing tweets onscreen deftly, if not brilliantly. You become aware as you watch that film’s an old medium, dating back to the century before last, and here it’s stretching out to try to deal with much newer media. Like listening to a radio drama about TV, or reading a book about film.

Formal issues aside, the movie has a lot on its mind. Gender is a running subtext. It’s never really discussed openly, but almost everything that happens is heavily gendered. Bad behaviour is almost universal, perhaps too much so — with Min almost the only woman in the movie, and her essentially in the past tense, her actions loom awfully large. We find out about her past as a bully; how are we to interpret it relative to what the young men do? The movie does avoid establishing any kind of equivalency, I think, given the way it ends. But again there’s a sense that the thematic investigation isn’t cutting deeply enough.

The twists are strong as far as they go. The revelations of the pasts of certain characters, and how they all intertwine, are clever and open up new scope for emotional exploration. But at the same time, the mystery plot is driving events forward. I can’t help but think that that’s a misstep; that the mystery and the slice-of-life concerns of the film are out of sync. The set-up, leading up to the point where Min’s body is found, is very strong. But after that, the plot stops being cutting. There’s a lack of emotional affect, a lack of anything startling. There is a level where the final revelations of the film can be seen as dissipating the mystery plot — but it’s just too late. Socialphobia isn’t a bad film. But after a strong opening it settles down to a kind of routine. As a result, when all’s said and done it’s not as good as it hinted at being. It feels like a missed opportunity.

(You can find links to all my 2015 Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.