Fantasia Diary 2015, Day 17: Synchronicity, The Dark Below, Traders, and Méliès et magie

Thursday, July 30, looked like one of the odder days I had lined up at the Fantasia Festival. I’d head down to the De Sève Theatre early on to catch a new American science-fiction film called Synchronicity, then go to the screening room to watch a dialogue-free horror film called The Dark Below. After that, I’d go back to the De Sève to catch the Irish black comedy Traders, and finally wrap up with an event called Méliès et magie, an event presenting some of the classic short films by the first master of fantasy cinema. It looked like a varied day, though in the end it was less so than I’d expected.

Thursday, July 30, looked like one of the odder days I had lined up at the Fantasia Festival. I’d head down to the De Sève Theatre early on to catch a new American science-fiction film called Synchronicity, then go to the screening room to watch a dialogue-free horror film called The Dark Below. After that, I’d go back to the De Sève to catch the Irish black comedy Traders, and finally wrap up with an event called Méliès et magie, an event presenting some of the classic short films by the first master of fantasy cinema. It looked like a varied day, though in the end it was less so than I’d expected.

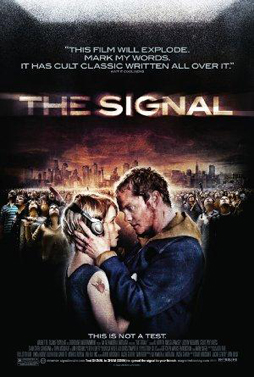

Synchronicity is directed by Jacob Gentry, known for his horror film The Signal, from a screenplay by Gentry and Alex Orr. It stars Chad McKnight as Jim Beale, the leader of a small team of physicists about to successfully achieve time travel — and Michael Ironside as a venture capitalist named Klaus Meisner angling to take over their invention, to play, as Meisner says, Edison to their Tesla. Caught in the middle is a mysterious woman named Abby (Brianne Davis) with ties to Meisner. Beale’s drawn to her, but whose side is she on? As the movie goes on, time loops back (or does it?) and events are reinterpreted. But then there’s a final revelation, and all we thought we knew is questioned.

I want to avoid giving away fundamental plot details. But I have to say the final twist of Synchronicity seems to me to be badly misjudged. It means not only that the logic we thought we were following up to that point was not true, but that there is no alternate logic to replace it. We’ve been watching a tissue of coincidences. It deflates the movie for me (and incidentally calls into question the intelligence of otherwise well-characterised scientists).

On a more nit-picking yet practical level, I couldn’t visualise what happened when the physicists’ machine was turned on — what sort of portal was opened. They’re expecting, and receive, a potted plant. But, and surely it’s no spoiler to say this, at various times a full-grown human goes through the machine as well. I would have liked slightly better-defined staging.

On a more nit-picking yet practical level, I couldn’t visualise what happened when the physicists’ machine was turned on — what sort of portal was opened. They’re expecting, and receive, a potted plant. But, and surely it’s no spoiler to say this, at various times a full-grown human goes through the machine as well. I would have liked slightly better-defined staging.

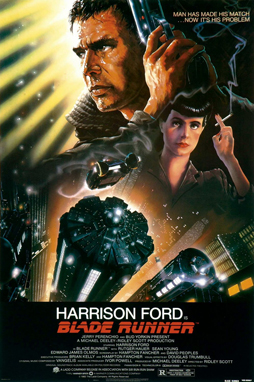

I’m putting these problems, large and small, up front because the movie does get an awful lot else right. Drenched in blue light, it’s a pleasure to watch. It’s often reminiscent of Blade Runner, in its imagery and its dreamy synthesizer score, but that’s not entirely a bad thing. The dialogue’s snappy and exposition handled well, the actors are solid, and the characters are for most part as smart as you’d expect of a group of scientists. One of the physicists, Matty (Scott Poythress), is clearly non-neurotypical. Abby swiftly develops into something quite different from a femme fatale. The plot’s generally non-standard.

Tonally, the movie’s spot on. The sense of a Blade Runner pastiche is meant, I think, to evoke the idea of science-fiction noir, which this is and isn’t. The sense of paranoia is prominent, as we follow Jim Beale and swiftly realise people are lying to him. Plotwise the movie makes no nod to Blade Runner, but set designs and lighting designs insist on the connection; Synchronicity seems then to actually expand on what Blade Runner suggested, broadening the film sub-genre it (arguably) started.

Tonally, the movie’s spot on. The sense of a Blade Runner pastiche is meant, I think, to evoke the idea of science-fiction noir, which this is and isn’t. The sense of paranoia is prominent, as we follow Jim Beale and swiftly realise people are lying to him. Plotwise the movie makes no nod to Blade Runner, but set designs and lighting designs insist on the connection; Synchronicity seems then to actually expand on what Blade Runner suggested, broadening the film sub-genre it (arguably) started.

Gentry has a strong eye, and creates a futuristic image of urban space. The actual time in which the movie’s set is kept appropriately vague, allowing it to be both present and future; both our world, and enough not our world that we can believe in time-travel. There’s nothing too futuristic here, so in that way it’s not like Blade Runner. But it also doesn’t quite feel like the present moment we know. It’s a successful ambiguity in a film that doesn’t always succeed at the ambiguous.

McKnight plays Jim Beale as an idealist, someone absolutely focussed on his theories and the nature of the universe. That’s good to see; someone motivated purely by a love of science. But then there’s Abby, and Beale’s also driven by a love for her — a very cinematic love, that comes out of nowhere and drives him (and to an extent her) to total obsession all at once. There is perhaps some hint by the end that this is a drama that’s been played out several times by slightly different entities, so that Jim and Abby actually have a kind of subliminal knowledge of each other. But it’s certainly not explored in any depth, and I think even to make the argument is something of a reach. So: Beale’s feelings for Abby come out of nowhere, and conflict with his earlier love for science. It’s possible to see the movie as an attempt by Beale to reconcile the two. I’m not sure it’s a successful reconciliation, if so.

Again, the late twist suggests his theories were misguided in certain crucial ways; after which we don’t really get his reaction. What do you do when the ideas that’ve sustained you for your adult life, the ideas that have fuelled all your ambitions, collapse? Well, Beale has an answer ready to hand, and that’s Abby. So the conflict’s easily resolved. Where then is the drama? What’s the point?

Again, the late twist suggests his theories were misguided in certain crucial ways; after which we don’t really get his reaction. What do you do when the ideas that’ve sustained you for your adult life, the ideas that have fuelled all your ambitions, collapse? Well, Beale has an answer ready to hand, and that’s Abby. So the conflict’s easily resolved. Where then is the drama? What’s the point?

Perhaps Beale attempting to escape the intrigue-filled world where capitalists plot to steal his dream is the point. Certainly by the end there’s a case to be made for seeing him as having learned that nothing is inevitable, and that the world around us is not the only world that can be. But I had no sense that he was seeking this kind of escape, not as such. He had much more specific goals, which the movie casually knocks down as possibilities, leaving him his love interest to wrap up the film. “Time is our only currency,” he argues, a striking line, but by the end it means nothing that I can see. The plot twist that resolves all the paradoxes opens things up too much, and eliminates too much of the film’s drama. Synchronicity remains highly watchable. But I can’t honestly recommend it.

From there I went on to see The Dark Below, directed by Douglas Schulze from a script by Schulze with Jonathan D’Ambrosio. It’s a horror movie that opens with a proverb: “Silence is the most powerful scream.” That’s relevant because the movie has only one line of dialogue, delivered early on: “Love is cold.” I share that because in the end the line comes to feel less resonant than it at first seems. It’s a good line, on its own, but carries weight it doesn’t earn. Which is not far from the movie as a whole.

It begins with a man fighting a woman, knocking her out, and dropping her into a hole in an ice-covered lake. As the wet-suit-clad woman struggles frantically for survival, we get flashbacks that fill in their backstory and why the man, Ben (David G.B. Brown), is trying to kill his wife, Rachel (Lauren Mae Shafer). All of this is done without dialogue.

It begins with a man fighting a woman, knocking her out, and dropping her into a hole in an ice-covered lake. As the wet-suit-clad woman struggles frantically for survival, we get flashbacks that fill in their backstory and why the man, Ben (David G.B. Brown), is trying to kill his wife, Rachel (Lauren Mae Shafer). All of this is done without dialogue.

It’s well shot, and uses special cameras for the underwater sequences, which apparently were really shot in a frozen lake. But the lack of dialogue feels like a gimmick. It makes sense for the present-day sequences of Rachel’s struggles to be wordless. It doesn’t particularly make sense for the flashbacks to be silent. It means that Schulze gets to display some fine visual storytelling, yes, but some sequences perhaps could have used a bit more definition. In particular, Veronica Cartwright has some scenes as (presumably) Rachel’s mother that feel underdeveloped. There’s a nice moment where she stares Ben down that does gain from the wordlessness. But too much else feels drawn out, and Schulze’s frequent use of slow-motion in the flashbacks doesn’t help. The movie’s only 75 minutes, but seems longer.

The conceit of wordlessness also only works because the plot’s rudimentary. It’s a horror movie with a human killer at the centre. Given that, everything unfolds as you’d expect. The climax has a disappointingly cliché fakeout sequence. And the very end has Rachel look twice at a seemingly everyday scene to realise — well, I’m not sure what. Watching this movie in the screening room, I couldn’t make out why the film paused. It’s a moment that’s placed in exactly the spot where a horror film usually puts in a coda undercutting the supposed triumph of goodness; but even after rewinding and freeze-framing, and then again after looking back through the film, I could not for the life of me figure out what I was supposed to take away from it.

The individual sequences of Rachel struggling to get free work well enough. The acting’s strong, and the actors all effectively convey emotion without words. Thematically there’s presumably a feminist take on the horror genre going on here, as Rachel (supported by her mother) struggles to overcome an exploitative man who’s a monstrous Cronus-like figure. So we go from him inflicting violence on her in the opening shots to her happy survival. But there’s ironically little depth to the movie. The concept’s fine. But it’s not fleshed out. It remains a concept alone. There’s too little ‘there’ there.

The individual sequences of Rachel struggling to get free work well enough. The acting’s strong, and the actors all effectively convey emotion without words. Thematically there’s presumably a feminist take on the horror genre going on here, as Rachel (supported by her mother) struggles to overcome an exploitative man who’s a monstrous Cronus-like figure. So we go from him inflicting violence on her in the opening shots to her happy survival. But there’s ironically little depth to the movie. The concept’s fine. But it’s not fleshed out. It remains a concept alone. There’s too little ‘there’ there.

I have to add that I had some questions about the movie’s backstory, as well. The flashback sequences cover years of Rachel and Ben’s life. We see them meet and fall in love and then some years of marriage together before Rachel learns that Ben’s a monster. And this is what I question: how it comes about that Rachel takes so long to realise what Ben is. We’re not talking about an adulterer or, so far as I can see, even a typical narcissist or psychopath. He seems much worse. So how is it Rachel doesn’t know? The earliest flashbacks seem to show her as an unsure person, insecure, and I can imagine her wanting Ben to be the person she imagines him to be. But I didn’t get that out of the picture as it is. And what of the people around her? Were they as surprised as she?

I don’t say there’s no answer to these questions. I am saying that they confused me enough that more answers in the film itself might have been helpful. There’s not enough made clear about the characters, in essence, much as the movie spends a certain amount of time on them. It seems to me to be a frequent tension in horror films: the focus on character versus the need to do terrible and typically fatal things to them. Conceptually, the balance is just about right here in terms of the amount of time given to Rachel’s struggles versus the amount of time given to the flashbacks — though I’d argue the flashbacks do collectively drag on. At any rate, the point is that without the specificity of dialogue, they don’t convey the character information that would let the movie flow more clearly.

I don’t say there’s no answer to these questions. I am saying that they confused me enough that more answers in the film itself might have been helpful. There’s not enough made clear about the characters, in essence, much as the movie spends a certain amount of time on them. It seems to me to be a frequent tension in horror films: the focus on character versus the need to do terrible and typically fatal things to them. Conceptually, the balance is just about right here in terms of the amount of time given to Rachel’s struggles versus the amount of time given to the flashbacks — though I’d argue the flashbacks do collectively drag on. At any rate, the point is that without the specificity of dialogue, they don’t convey the character information that would let the movie flow more clearly.

Film is a visual medium, but visuals alone are an inefficient way to tell stories. It can be done, and done brilliantly. But The Dark Below ends up an argument in favour of judiciously-deployed words.

From the screening room I returned to the De Sève to watch Traders, which was preceded by a short film: “Pulitzer,” written and directed by Riley James. It follows a jaded news photographer (Cassandra Magrath) in a war zone as the war nears its end. She’s desperate to get a last picture before the shooting stops, something that’ll make her name and get her a Pulitzer prize. She thinks she comes across a situation that’ll do it, but bad luck gets in her way, leading to a series of increasingly cynical attempts to get the shot she wants anyway. It’s not a bad idea, but it’s less than convincing, as the photographer makes some unforced errors that seem too convenient. The comedy plays, the cynicism about the media’s bracing, but the logic’s a bit strained.

From the screening room I returned to the De Sève to watch Traders, which was preceded by a short film: “Pulitzer,” written and directed by Riley James. It follows a jaded news photographer (Cassandra Magrath) in a war zone as the war nears its end. She’s desperate to get a last picture before the shooting stops, something that’ll make her name and get her a Pulitzer prize. She thinks she comes across a situation that’ll do it, but bad luck gets in her way, leading to a series of increasingly cynical attempts to get the shot she wants anyway. It’s not a bad idea, but it’s less than convincing, as the photographer makes some unforced errors that seem too convenient. The comedy plays, the cynicism about the media’s bracing, but the logic’s a bit strained.

Traders was co-written and co-directed by Rachael Moriarty and Peter Murphy. It begins with the collapse of an Irish asset management firm. Now unemployed, Harry Fox (Killian Scott) and Vernon Stynes (John Bradley, Samwell Tarly on Game of Thrones) scramble for work and money. The nerdy Vernon hits on something: he realises that with every one percent rise in unemployment, suicides rise eight percent. He hatches a scheme, creating a web site offering an alternative to suicide: two people who’ve decided to die anyway can anonymously agree to meet up for a winner-take-all fight to the death over all their worldly possession. The winner walks away with all the cash. The loser is no worse off than they would have been anyway. The site becomes a hit. Harry’s dragged into signing up. And wins. And then comes back.

It’s an effective film. The acting’s strong, the camerawork solid. There’s a voice-over moving the plot along, and it’s handled well. The basic concepts of the movie, and the number of different subplots that develop, are complex enough that having a narrator — Harry — is genuinely useful. It’s all bracingly intelligent.

It’s an effective film. The acting’s strong, the camerawork solid. There’s a voice-over moving the plot along, and it’s handled well. The basic concepts of the movie, and the number of different subplots that develop, are complex enough that having a narrator — Harry — is genuinely useful. It’s all bracingly intelligent.

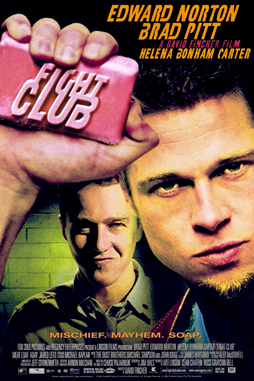

That said, I felt Traders didn’t push its subject quite as far as it could have. It does maintain a black tone, but doesn’t go for the truly acidic. It touches on economic issues, on the nature of masculinity, on violence and how it relates to the foregoing — it deals, basically, with some of the same themes as Fight Club. But it lacks that movie’s flash or extravagance; it lacks David Fincher, maybe, though that undersells the effective direction Traders does have.

The directors choose to keep Harry at the centre fo the film and to keep him as a sympathetic character. We cheer him as he wins fight after fight; he’s smart and no-bullshit and competent. We’re cheering for him to become more and more of a hard man, better and better at what he does and thus more and more brutal. By the end he seems to be on top of things, but the last shots make it clear he’s trapped in a spiral. It’s a spiral that entertains us, perhaps too easily. I assume the idea is to make us complicit in Harry’s violence. I feel the movie makes it too easy to see his point of view.

The directors choose to keep Harry at the centre fo the film and to keep him as a sympathetic character. We cheer him as he wins fight after fight; he’s smart and no-bullshit and competent. We’re cheering for him to become more and more of a hard man, better and better at what he does and thus more and more brutal. By the end he seems to be on top of things, but the last shots make it clear he’s trapped in a spiral. It’s a spiral that entertains us, perhaps too easily. I assume the idea is to make us complicit in Harry’s violence. I feel the movie makes it too easy to see his point of view.

Put it this way: the movie’s oddly similar to Marvel’s Daredevil TV show. A violent man, good at violence but troubled by it, who we cheer for as he wreaks havoc on people who come up against him; he takes more and more damage, but levels up as he goes. He angsts about what he does, but we know he’s not going to change. Daredevil has some kind of redemption angle, and a concern with good and evil — it dealt more-or-less directly with the question of whether vigiliantism is ever right, and allows characters to make good arguments against it. Traders, to its credit, is unconcerned with redemption, and perfectly willing to make its hero the villain. The pudgy sidekick isn’t funny or eloquent, but off-putting and socially awkward to the point of inappropriateness. But if it shuns the idea of heroism, it also doesn’t have the moral standing of really bitter satire — it follows Harry so closely his perspective dominates the film, and since he quickly makes his peace with what he does, it’s difficult to argue against him. There isn’t enough ground given. Particularly when a group of low-rent gangsters get involved in the scheme, next to whom even an incipient psychopath like Harry looks good.

There is, then, a sense in which the movie doesn’t just allow Harry to be sympathetic to us by dint of being the main character, but actively conspires to make him heroic. Most of the people he fights, most of the people who sign on to Vernon’s scheme, are men; and when a woman combatant is introduced, the movie doesn’t allow the actual fight to take place. Harry always comes off as sympathetic. By contrast, when you look at Vernon, you see the typical nerd — the beta male (or gamma, or omega, or whatever Greek letter you like) to Harry’s alpha. I felt the movie shortchanged Vernon; a man smart enough to come up with the fighting scheme, and to work out a reasonably effective protocol for the fighters to meet and find a battleground, ought to be smarter than he’s shown to be. But Vernon’s incompetence makes us appreciate Harry the more. If I’d thought that was deliberate, if I’d thought Harry was designed to be an unreliable narrator who was (consciously or unconsciously) talking up his own share of things, then I’d have no problem. But I couldn’t find any way to read the film so as to suggest that’s what was happening.

There is, then, a sense in which the movie doesn’t just allow Harry to be sympathetic to us by dint of being the main character, but actively conspires to make him heroic. Most of the people he fights, most of the people who sign on to Vernon’s scheme, are men; and when a woman combatant is introduced, the movie doesn’t allow the actual fight to take place. Harry always comes off as sympathetic. By contrast, when you look at Vernon, you see the typical nerd — the beta male (or gamma, or omega, or whatever Greek letter you like) to Harry’s alpha. I felt the movie shortchanged Vernon; a man smart enough to come up with the fighting scheme, and to work out a reasonably effective protocol for the fighters to meet and find a battleground, ought to be smarter than he’s shown to be. But Vernon’s incompetence makes us appreciate Harry the more. If I’d thought that was deliberate, if I’d thought Harry was designed to be an unreliable narrator who was (consciously or unconsciously) talking up his own share of things, then I’d have no problem. But I couldn’t find any way to read the film so as to suggest that’s what was happening.

It’s ultimately an effective movie, but not a challenging one, not at the level it perhaps could have been. The violence is relatively realistic, which is good, but at a certain point you wonder why martial artists and the like aren’t getting involved. Criminals, or one group of criminals, do start to move in on the scheme, and start cheating — but they’re fairly half-assed as criminals go. That said, the movie does move fast enough that you don’t notice the logic problems (why the Irish authorities aren’t worrying about so many suicides in one restricted geographical area, and what happens when the bodies start coming to light, and so forth).

It’s ultimately an effective movie, but not a challenging one, not at the level it perhaps could have been. The violence is relatively realistic, which is good, but at a certain point you wonder why martial artists and the like aren’t getting involved. Criminals, or one group of criminals, do start to move in on the scheme, and start cheating — but they’re fairly half-assed as criminals go. That said, the movie does move fast enough that you don’t notice the logic problems (why the Irish authorities aren’t worrying about so many suicides in one restricted geographical area, and what happens when the bodies start coming to light, and so forth).

The central idea of the film seems to be a comparison of stockbrokers and psychopaths. It’s a good idea, and Vernon’s scheme is a good central notion to play out on a large scale. The movie’s recurrent images of burned-out men fighting to the death in post-industrial waste land is powerful. And you do wonder what to make of Harry. Once he starts killing people he takes to it easily. There’s a clever structural point that makes things clear: the movie opens in medias res, with Harry involved in a fight. Eventually the movie works its way back around to that fight, and we realise that it’s not a plot-central fight. It’s just a point where he crosses a certain line, where it no longer becomes possible to argue this is all a victimless crime. It’s a canny move, and points to the intelligence underlying this film. It’s funny and quick and occasionally brutal. But it feels like a little more daring might have gone a long way; like it could have pushed itself and its audience further.

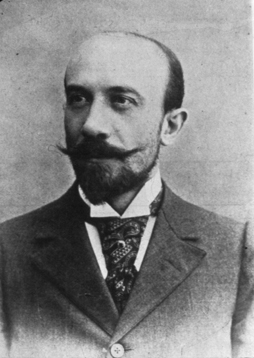

Next up came Méliès et magie (Méliès and Magic). This was a presentation of several short silent films by Georges Méliès. In-between, a stage magician would perform, meant to hearken back to Méliès’ pre-film career — an accomplished stage magician, he owned the Théâtre Robert-Houdin founded by the famous magician of the same name. Méliès performed there, integrating film projection into his act from 1896 onward. He grew more interested in the new medium, eventually working out various techniques of what are now called special effects. His shorts were landmarks in the development of fantasy film; that night Fantasia was giving an audience the chance to see a few of them on the big screen.

Next up came Méliès et magie (Méliès and Magic). This was a presentation of several short silent films by Georges Méliès. In-between, a stage magician would perform, meant to hearken back to Méliès’ pre-film career — an accomplished stage magician, he owned the Théâtre Robert-Houdin founded by the famous magician of the same name. Méliès performed there, integrating film projection into his act from 1896 onward. He grew more interested in the new medium, eventually working out various techniques of what are now called special effects. His shorts were landmarks in the development of fantasy film; that night Fantasia was giving an audience the chance to see a few of them on the big screen.

You saw at once as you walked in that the De Sève Theatre was dressed up for the occasion. There’s a small stage before the screen, and tonight it was decked out with old chests, flowers, candles, rugs, a skull, and various pieces of antique machinery — including a very old film camera. Philip Spurrell from the Ciné-club Montréal gave an introduction in French and English. The Ciné-club was co-presenting the evening with Fantasia; the club regularly hosts screenings of classic films, including live musical performances when, as here, showing silent movies. Spurrell introduced the night’s musician, Shayne Gryn on piano (as a disclaimer I’ll note that Shayne’s a friend of mine), and then brought out the magician, Vincent Pimparé (in formal wear), with his lovely assistant Zelda Blue (AKA Jessica Rae, in the cotume of a 1920s flapper). Spurrell noted that the old film projector on stage dated from 1914, and gave a brief introduction to the films that would follow.

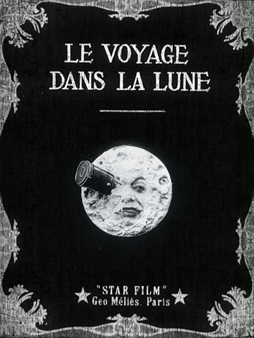

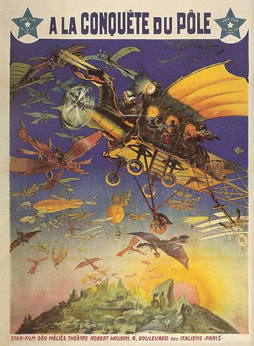

The first movie shown was actually a documentary from 1952, Georges Franju’s Le Grand Méliès, which covered Méliès’ life and career. Méliès’ son played his father, and Méliès’ second wife, then 87, had a major part in the film. It gave a solid introduction to Méliès’ life and techniques, with extensive clips from his most famous movies. After the film, Pimparé and Blue performed some magic tricks: rings slipped in and out of other rings. Then the first of Méliès’ films was shown, 1902’s Voyage dans la Lune (A Trip to the Moon), in which a group of astronomers travel by cannon to the Moon, where they encounter various wonders. After that Pimparé and Blue performed tricks with ropes that split apart and joined together, with boxes opening into other boxes. Then came 1903’s Le Royaume des feés (The Kingdom of the Fairies), showing a princess abducted by a witch, and the great quest launched to free her. Pimparé and Blue performed some cup-and-ball tricks, and then we saw Les Quat’Cents Farces du diable (The Merry Frolics of Satan), from 1906; a man deals with the Devil, leading to zany pranks and, finally, a bad end. Pimparé then hypnotised Zelda Blue, who performed a tap dance. 1911’s À la conquête du Pôle (The Conquest of the Pole) was next, an epic showing an international group of explorers seeking the pole and falling afoul of giants and other dangers; afterward came an attempt at telepathy from Pimparé and Blue that unfortunately didn’t come off. The evening concluded with 1912’s Le Chevalier des Neiges (The Knight of the Snows). Again Satan meddles with human life, this time called up by an evil knight, at whose command he captures yet another princess; the knight of the title seeks her out and recovers her, at which point Satan drags his mortal pawn down to hell. It had been, by the time all was said and done, quite dizzying.

The first movie shown was actually a documentary from 1952, Georges Franju’s Le Grand Méliès, which covered Méliès’ life and career. Méliès’ son played his father, and Méliès’ second wife, then 87, had a major part in the film. It gave a solid introduction to Méliès’ life and techniques, with extensive clips from his most famous movies. After the film, Pimparé and Blue performed some magic tricks: rings slipped in and out of other rings. Then the first of Méliès’ films was shown, 1902’s Voyage dans la Lune (A Trip to the Moon), in which a group of astronomers travel by cannon to the Moon, where they encounter various wonders. After that Pimparé and Blue performed tricks with ropes that split apart and joined together, with boxes opening into other boxes. Then came 1903’s Le Royaume des feés (The Kingdom of the Fairies), showing a princess abducted by a witch, and the great quest launched to free her. Pimparé and Blue performed some cup-and-ball tricks, and then we saw Les Quat’Cents Farces du diable (The Merry Frolics of Satan), from 1906; a man deals with the Devil, leading to zany pranks and, finally, a bad end. Pimparé then hypnotised Zelda Blue, who performed a tap dance. 1911’s À la conquête du Pôle (The Conquest of the Pole) was next, an epic showing an international group of explorers seeking the pole and falling afoul of giants and other dangers; afterward came an attempt at telepathy from Pimparé and Blue that unfortunately didn’t come off. The evening concluded with 1912’s Le Chevalier des Neiges (The Knight of the Snows). Again Satan meddles with human life, this time called up by an evil knight, at whose command he captures yet another princess; the knight of the title seeks her out and recovers her, at which point Satan drags his mortal pawn down to hell. It had been, by the time all was said and done, quite dizzying.

You could see Méliès developing, refining, and repeating several of his techniques in these films. Double-exposures, stop tricks, animation, Méliès uses them all along with practical effects like trapdoors and smoke bombs. He doesn’t necessarily use them one-at-a-time, either, often filling the frame with actors and acrobats and costumes and all kinds of motion. And everything is always changing into everything else. Moon-men disappear in puffs of smoke; demons come out of the woodwork. There’s an almost polymorphous aspect to Méliès’ work, a constant shifting from one form to another: anything can become anything else, and probably will.

The actual images he creates are often beautiful. The witch in Le Royaume des feés carrying the princess away through the night sky while the court below watches helplessly; the ruined castle to which the Knight of the Snows journeys on his rescue mission; above all, perhaps, that famous shot of a displeased Moon with a rocket in its eye, one of the truly iconic images in cinema. Méliès had a strong sense of composition and grasped intuitively that cinema is the art of the moving image — things are always happening, something’s always there to draw the eye on to other pictures, other wonders.

The actual images he creates are often beautiful. The witch in Le Royaume des feés carrying the princess away through the night sky while the court below watches helplessly; the ruined castle to which the Knight of the Snows journeys on his rescue mission; above all, perhaps, that famous shot of a displeased Moon with a rocket in its eye, one of the truly iconic images in cinema. Méliès had a strong sense of composition and grasped intuitively that cinema is the art of the moving image — things are always happening, something’s always there to draw the eye on to other pictures, other wonders.

Costumes are elaborate, if highly romanticised, and set designs are atmospheric and effective. But primarily these movies show a knack for story. Méliès didn’t use intertitles, so none of the characters are given names onscreen, and the story’s told purely visually. But the main points of the stories are communicated effectively. Admittedly, most of them are basic, if not familiar: there’s a fairy-tale-like sense to many of them. In fact, looking around the internet at the detailed plots worked out for his films, I note that some at least were based on pre-existing pantomime stories, which is logical enough.

The fairy-tale feel, present even in a nominally science-fictional work like Voyage dans la Lune, fits perfectly with the techniques Méliès invented. To judge by these stories, Méliès liked using the quest form and the fairy-tale form: structures which allowed him to come up with wild scenery, costumes, and magic. Along with that, Méliès used Satan as a character in ways that remind me of Satan’s appearances in the Grimms’ fairy-tale collection: he’s a plot mechanic, a way to get the story going. But then the zaniness Satan unleashes also calls to mind some of the older versions of the Faust story. So Satan, played (at least in these movies) by Méliès himself, acts as a kind of infernal ringmaster, bringing mayhem and a carnivalesque atmosphere to the world.

Sometimes Méliès does seem too invested in the crazy things he can make happen on screen. There’s a lot of knockabout humour, and Les Quat’Cents Farces du diable in particular feels a bit underwritten, the story vestigial. Le Chevalier des Neiges has an odd structure, as Satanic gags early on take up a lot — indeed too much — of the film’s running time.

Sometimes Méliès does seem too invested in the crazy things he can make happen on screen. There’s a lot of knockabout humour, and Les Quat’Cents Farces du diable in particular feels a bit underwritten, the story vestigial. Le Chevalier des Neiges has an odd structure, as Satanic gags early on take up a lot — indeed too much — of the film’s running time.

But then, Méliès was literally making things up as he was going along. Try to imagine seeing these things back in the first decade of the twentieth century, and you can see there’s a sense of newness to a lot of what Méliès does. There’s an almost steampunk-esque mix of technology and fantasy in Voyage dans la Lune, for example, with a scene of the moon rocket being constructed in an industrial plant, then a dissolve to wealthy spectators taking their place on the rooftops of a city overlooking factory smokestacks. Or consider the airplane of the explorers in À la conquête du Pôle.

Méliès mixes old and new at whim, as well, envisioning an association of scientists in Voyage dans la Lune who resemble alchemists and wizards. He certainly wasn’t shy in responding to his times; the international group of explorers in À la conquête du Pôle include representatives from China and Japan, but are an all-male group who have the cops chase away a group of suffragettes who want to go to the pole themselves and end up briefly competing with the male explorers. Still, over a hundred years on, we’re far enough away from Méliès that new meanings have accrued that he could not have imagined: as witness the costumed figures at the hanging scene in Le Chevalier des Neiges, at the time identifiable as penitents, today resembling robed members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Méliès mixes old and new at whim, as well, envisioning an association of scientists in Voyage dans la Lune who resemble alchemists and wizards. He certainly wasn’t shy in responding to his times; the international group of explorers in À la conquête du Pôle include representatives from China and Japan, but are an all-male group who have the cops chase away a group of suffragettes who want to go to the pole themselves and end up briefly competing with the male explorers. Still, over a hundred years on, we’re far enough away from Méliès that new meanings have accrued that he could not have imagined: as witness the costumed figures at the hanging scene in Le Chevalier des Neiges, at the time identifiable as penitents, today resembling robed members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Still, the raw imaginative power needed to conceive of these films, the exuberance they capture, remains. Méliès was a technological visionary, using a new invention to tell traditional tales — and create a tradition of his own. His films are still entertaining, in their zest and energy and artfulness. At the end of that Thursday, I’d seen three decent films that did various things cleverly, to greater or lesser effect; and then, watching Méliès’ works, I saw masterpieces. It was a healthy reminder of what magic really is, from the first man who put magic in the movies.

(You can find links to all my 2015 Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.