Two Great Books by Poul Anderson: The High Crusade and The Golden Slave

If Three Hearts and Three Lions owes something to A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, then so does The High Crusade. But The High Crusade inverts Mark Twain’s concept. This book isn’t written by a modern who time traveled to Arthur’s court, but rather is written by a medieval scribe who witnessed Sir Roger Baron de Tourneville and his knights and court invade an alien spaceship and end up using it to conquer a major portion of interstellar Space. The bookends are provided by a space captain of Earth’s future space age, who hardly can believe, by reading the contained epistle, that humans from the Middle Ages have been in space for some time now and even have established a Holy Galactic Empire. Add to this, at the plot’s center, a courtly betrayal through a love triangle much like that of Arthur’s, Guinevere’s and Lancelot’s.

If Three Hearts and Three Lions owes something to A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, then so does The High Crusade. But The High Crusade inverts Mark Twain’s concept. This book isn’t written by a modern who time traveled to Arthur’s court, but rather is written by a medieval scribe who witnessed Sir Roger Baron de Tourneville and his knights and court invade an alien spaceship and end up using it to conquer a major portion of interstellar Space. The bookends are provided by a space captain of Earth’s future space age, who hardly can believe, by reading the contained epistle, that humans from the Middle Ages have been in space for some time now and even have established a Holy Galactic Empire. Add to this, at the plot’s center, a courtly betrayal through a love triangle much like that of Arthur’s, Guinevere’s and Lancelot’s.

This book is really good. It’s a fast, enjoyable read. It was serialized originally in Astounding magazine as that publication was changing its name to Analog. When the book was published as a novel, it lost out on a 1961 Hugo to Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s A Canticle for Leibowitz. I find it interesting that Miller’s work, along with Anderson’s The High Crusade, limned medieval perspectives on futuristic landscapes. Perhaps this was the zeitgeist of the time. I read Baen’s edition of The High Crusade, which begins with a number of appreciations. This edition also contains a coda in the form of a short story called “Quest”, which takes place in the universe of The High Crusade. If the novel is a take on the Arthurian love triangle, then this story is a take on Galahad’s quest for the holy grail.

Also really good is what Wikipedia calls a historical novel and what Zebra, one publisher, calls heroic fantasy, though I certainly see no reason to quibble about terms of genre, and I’m guessing that terms were not so rigid in 1960 (or even in 1980, which is the date of the revised Zebra edition). I am talking about Poul Anderson’s The Golden Slave.

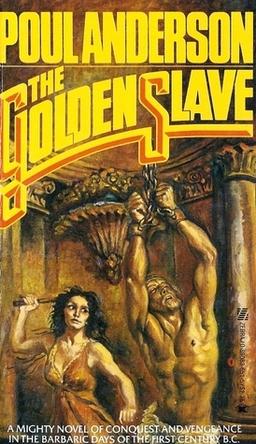

I have to say that the book was surprisingly good. This was because the cover of my Zebra edition lowered my expectations. Another cover edition doesn’t promise much else. The first cover suggests a bit of sado masochist fantasy. The second (given further below) highlights the sexual aspect of the book. It’s interesting that what is depicted on the Zebra edition never happens in this novel – not at least “on stage.” I assume that the woman on both of these covers is supposed to be Cordelia, a Roman lady who exploits her “golden slave” for sexual favors. What is interesting is that, however flawed their representations may be, the subject matter that these covers depict comprise – and this is a generous estimate – only the first act of the novel (if we divide the book roughly into three acts). Therefore, not for the first time, and I’m certain not for the last, I muse on how books are marketed to what publishers imagine their audiences might be. In a discussion of Virgin Planet, Rich Horton informed me that Virgin Planet was indeed written with a specific purpose in mind. The content of The Golden Slave, however, doesn’t seem to meet the promise of the covers – or at least does so insubstantially. In actuality, the book transcends its promise. As the title might suggest, The Golden Slave proves to be a profound meditation on slavery.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not suggesting that there isn’t a fair amount of sex in this book. The man on the covers, Eodan, certainly gets his share of amorous attentions. When the novel starts, Eodan is a free man, in love with his mate Hwicca. They have an infant son together, whom they have named Othrik. Eodan also has a Roman nobleman, Flavius, as a slave, a noble whom he captured during a military engagement with Rome. When Eodan – a Cimbrian – and others in a loose confederation of barbarian tribes are conquered by Marius’s Roman legions, both Eodan and Hwicca are taken by Flavius to now serve him as slaves. (To prevent this fate from happening likewise to her infant son, just before her own capture Hwicca dashes out Othrik’s brains on a nearby wagon wheel.)

Eodan and Hwicca are kept on different estates – Eodan on the farm, wherein he first is primarily used as a laborer, and Hwicca in a palace in Rome as Flavius’s concubine. Eodan at length rises in his position by receiving the attention of Flavius’s neglected wife Cordelia, and eventually joins with a female Greek slave, Phryne, to run away to Rome and rescue Hwicca from her captivity. The three attempt to eventually return to the northlands, where they believe they once again may be free.

Let me repeat myself. This book is great. Hopefully my readers can see the outlines of yet another Andersonian love triangle, one I first encountered in Three Hearts and Three Lions. But in this case the representation of the women is better. And this may be because of Anderson’s theme of slavery. Eodan, through his sexual submission to his owner Cordelia, gets to understand in part what it must be like to be a woman, “free” or not, in patriarchal Rome. And Cordelia, meaning to keep Eodan as a lover, explains what she must do, as a “free woman,” to have her way. She must convince men in her life – her father, in particular – to allow her an honorable divorce. Then she must marry again, but this time she hopes to be yoked to “[s]ome Senator, doddering with age, and very rich… Then [Cordelia says] you can be brought to Rome, Hercules [Cordelia’s pet name for Eodan]. There will be wealth for you… many slaves are wealthy in their own right – or you can even be freed, if you think a change of title makes any difference … It does not. You already have me in freehold.”

This passage shows the limits of Cordelia’s female “freedoms” in the patriarchal Roman state, but it shows also Eodan’s first experiences with slavery – his name change, Cordelia’s incapacity to understand how Eodan might want freedom, because as her lover she is willing to provide him with all he might require. She believes that this should be enough for Eodan. Why should he need more? But Eodan is increasingly aware of how fickle a lover Cordelia can be, how often Cordelia asserts her supremacy whenever Eodan exhibits preferences contrary to her own, and he even finds his sexual duties hollow and unfulfilling, which must be how many women feel within traditional marriage bonds.

Delightfully, this sort of relationship is commented on again when Eodan, with Phryne’s aid, attempts to rescue Hwicca. As with the triangle in Three Hearts and Three Lions, the reader of this novel easily intuits that Eodan is supposed to be with Phryne – even though Hwicca in no way is depicted as the “unworthy one…” Except for this: quite naturally, when Eodan appears to “rescue” Hwicca from her life of luxury as a concubine, Hwicca finds herself conflicted, not in the least because she might have a genuine relationship with Flavius. Perhaps feeling that, in her culture, she needs some defense for this behavior, she explains to Eodan that she thought that he was dead. And her relationship with Flavius is skillfully foreshadowed at the beginning of the book. While Flavius had been her slave, the two had spent a lot of time together. Flavius is so charming and attractive that Eodan even exhibits some jealousy.

Still, with Flavius now, Hwicca is not precisely “free,” so she reluctantly agrees to escape with Eodan and Phryne. To complicate matters even more, to achieve their escape, it is necessary for the three of them to keep Flavius as a hostage, even though it means they must be eternally vigilant over this crafty and conniving man.

Flavius is one of the best characters in the book. He is a villain, but a delightfully charming one. With nearly superhuman tenacity he hounds and pesters Eodan, possibly because he has genuine affections for Hwicca, and blames Eodan for Hwicca’s accidental slaying beneath Flavius’s own swinging sword, which had been meant for Eodan. Hwicca’s untimely death is perhaps my only criticism of the entire book – Anderson in effect kills off Hwicca partway through, right after Hwicca, after some considerable tension, has chosen to take up her place again as Eodan’s faithful wife and helpmeet, even though their relationship now clearly is estranged and Phryne and Eodan have oodles more passion and chemistry between themselves. I believe it would have been much more interesting – and thematic – to keep Hwicca alive and really ratchet up the tension in the triangle – or quadrangle, because it certainly didn’t seem unlikely that Hwicca might choose Flavius over Eodan.

Flavius is one of the best characters in the book. He is a villain, but a delightfully charming one. With nearly superhuman tenacity he hounds and pesters Eodan, possibly because he has genuine affections for Hwicca, and blames Eodan for Hwicca’s accidental slaying beneath Flavius’s own swinging sword, which had been meant for Eodan. Hwicca’s untimely death is perhaps my only criticism of the entire book – Anderson in effect kills off Hwicca partway through, right after Hwicca, after some considerable tension, has chosen to take up her place again as Eodan’s faithful wife and helpmeet, even though their relationship now clearly is estranged and Phryne and Eodan have oodles more passion and chemistry between themselves. I believe it would have been much more interesting – and thematic – to keep Hwicca alive and really ratchet up the tension in the triangle – or quadrangle, because it certainly didn’t seem unlikely that Hwicca might choose Flavius over Eodan.

Flavius is the one who, in a conversation with Phryne, provides the best words as a lynchpin for Anderson’s theme, and elevates the discussion about slavery to a philosophical, metaphysical level:

There are no free and unfree; we are all whirled on our way like dead leaves, from an unlikely beginning to a ludicrous end. I do not speak to you now; the sounds that come from my mouth are made by chance, flickering within the bounds of causation and natural law. Truly, we are all slaves. The sole difference lies between the noble and ignoble.

It is Flavius who also provides the language that shows how women enjoy the least freedom. Again he says to Phryne,

I say to you … the slave-brand is on you. … Oh, if the gods I do not believe in are cruel enough to grant your wish [of freedom], you could give your body to some North-dweller – you could learn his hog-language and pick the lice from his hair and bear him another squalling brat every year, till they bury you toothless at forty years of age in a peat bog where it always rains. That could happen. But your soul would forever be chained by the Midworld Sea.

This shows that even free women are “free” only insofar as they choose the men that will be with them and dominate them. Flavius’s description of Phryne’s choices may very well describe Cordelia’s choices as a Roman lady at the beginning of the book. In fact, Phryne eventually is faced with the offer of being the celebrated, pampered concubine of Mithradates, one of the most powerful, learned, and fair kings in all the world – and neither Eodan nor his most trusted companion, Tjorr, can understand why she isn’t ecstatic at the prospect. Why, her fortune is set!

Phryne escapes Mithradates’s affections, and Eodan sacrifices his position as Mithradates’s general to go after her. Tjorr and his lucky hammer join Eodan, and, a day later, Flavius and his Romans pursue them all for one final confrontation. It was about this time that I smacked my forehead with my palm. I felt as silly as I did when it was “revealed” in Neil Gaiman’s American Gods just who was this fellow prison inmate of Shadow’s: “Low Key.” Eodan – Odin. Tjorr (not even the lucky hammer was enough of a giveaway for me) – Thor. Phryne – Freya. At the novel’s denouement, it becomes clear that a secondary purpose of this book was to provide an origin story for Viking myth and culture, much in the tradition of Snorri Sturluson who, in his Prose Edda, has explained that “Voden whom we call Odin … was a man famed for his wisdom and every kind of accomplishment. His wife was called Frigida, whom we call Frigg.” In Jean I. Young’s translation, Sturluson continues,

Odin, and also his wife, had the gift of prophecy, and by means of this magic art he discovered that his name would be famous in the northern part of the world and honoured above that of all kings. For this reason he set out on a journey from Turkey. He was accompanied by a great host of old and young, men and women, and they had with them many valuables. Through whatever lands they went such glorious exploits were related of them and they were looked on as gods rather than men. They did not halt in their journey until they came to the north of the country now called Germany.

The closing act of The Golden Slave hits a tone that had been playing in only minor key beforehand. For some time Eodan has expressed his belief that some “Power” is riding with him, a belief that Flavius frequently counters with his own cynical belief in “chance” alone. But at the closing of the novel this Power begins to be revealed as what will later be known as Odin’s legacy. A very moving passage has Eodan, bivouacked, falling to sleep one night. At this time, Eodan believes that Phryne, whom he and Tjorr have been tracking, is dead. “I am the wind,” he thinks.

The closing act of The Golden Slave hits a tone that had been playing in only minor key beforehand. For some time Eodan has expressed his belief that some “Power” is riding with him, a belief that Flavius frequently counters with his own cynical belief in “chance” alone. But at the closing of the novel this Power begins to be revealed as what will later be known as Odin’s legacy. A very moving passage has Eodan, bivouacked, falling to sleep one night. At this time, Eodan believes that Phryne, whom he and Tjorr have been tracking, is dead. “I am the wind,” he thinks.

He lay listening to himself blow across the earth, in darkness, in darkness, and the unrestful slain Cimbri rushing through the sky behind him. He searched all those evil plains for Phryne; the whole night became his search, for Phryne’s ghost. There were many skulls strewn in the long dead grasses, for this land was very old. But none of them was hers, and none of them could tell him anything of her; they only gave him back his own empty whistling. He searched farther, up over the Caucasus glaciers and then down to a sea that roared under his lash, until finally he came riding past a bloody-breasted hound, through sounding caves to the gates of hell; hoofs rang hollow as he circled hell, calling Phryne’s name, but there was no answer. Though he shook his spear beneath black walls, no one stirred, no one spoke, even the echoes died. So he knew that hell was dead, and it had long ago been deserted; and he rode back to the upper world feeling loneliness horrible within him. And centuries had passed while he was gone. It was spring again. He rode by the grave mound of a warrior named Eodan, which stood out on the edge of the world where the wind was forever blowing; and on the sheltered side he saw a coltsfoot bloom, the first flower of spring.

Pretty great, huh? This is some sort of true vision, for he is awakened, in the morning, to Tjorr’s comment that “There is light enough now.” And Eodan tells Tjorr that “Phryne lives.” Here is where the text gets seemingly intentionally ambiguous. Though Eodan quite clearly had some sort of vision, when Tjorr prepares to pour out a libation and say, “I would name the god this is for, if you will tell me who sent you that vision,” Eodan reasons that it is not a true vision but (contrary to the sweeping majesty that we have only just read) only his simple considerations that Phryne is intelligent and would have taken certain actions that Eodan had not yet considered. “I have no arts of the mage,” Eodan concludes. “I only think.”

And now Eodan’s weird is fully upon him. After all his experiences with kings and slaves, he decides on the following:

A king, he thought, was rightfully more than power. He should be law. Yes, and a bringer of goodly arts; a just man, who tamed wild folks more by his law than his spear – though he was also the one who taught them how to make war when war was needed – as far as the jealous gods allowed, a king should be freedom.

And afterward, he thought wryly, when the king was dead, the people would bring back the reeking past in his now holy name. But no, not quite all of it. Doubtless men slid back two steps for every three they made; nevertheless, the third step endured, and it was the king’s.

So, though Eodan would grow into the god Odin and, with his expiration, enable his followers to slide back into superstitious ancestor-worship, in time his example may give rise to the form of democracy that the Viking colonists in Iceland devised hundreds of years later. Contrary to the content that the two book covers might suggest, The Golden Slave proves to be an exciting meditation on government, belief, causality, and freedom.

There’s a movie version of THE HIGH CRUSADE that I used to have on VHS tape. It was pretty bad.

I never read The High Crusade, but The Golden Slave was a pretty grand adventure romp. Kudos for drawing attention to it, Gabe!

I am kind of glad that you read Golden Slave for us. It sounds mind blowing, but at the same time I can’t quite muster the energy to actually read it!

High Crusade, hower, is an amazing rollicking read.

[…] in The Golden Slave (and to lesser degrees in Three Hearts and Three Lions and in Virgin Planet) the major textures of […]

[…] recently Gabe Dybing covered another of my favorite Anderson novels, The Golden Slave at Black Gate (along with The High Crusade, one I haven’t […]