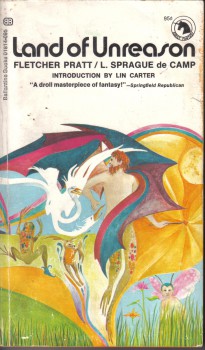

The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series: Land of Unreason by Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp

Land of Unreason

Land of Unreason

Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp

Ballantine Books (240 pages, January 1970, $0.95)

Cover art by Donna Violetti

Lin Carter ended the inaugural year of the BAF series with a reprint of a novel from the pulp Unknown, Hannes Bok’s The Sorcerer’s Ship. His first selection for the series’ first full calendar year was another tale from Unknown (the October 1941 issue), a collaboration between Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp.

Land of Unreason followed the first two Harold Shea stories among their collaborations. In this story, they introduce a new character, a young diplomat named Fred Barber, who is taking a medical rest in the Irish country-side.

One night, he notices his hostess leaving some milk out for the fairies, so that her infant son won’t be taken and a changeling left in his place. Fred is contemplating his bottle of single malt to help him get to sleep and decides he’s rather have the milk since that has been his proven cure for insomnia all his life. Also, milk is strictly rationed, and he doesn’t want to see it wasted. He drinks most of it, leaving just a little, into which he pours a generous amount of his whiskey.

Fred then goes to bed and quickly drops off to sleep. The fairy who finds the whiskey drinks it and gets plastered. Since he didn’t get any milk, he goes into the house to take the baby and leave a changeling. Only in his inebriated state, he takes Fred rather than the infant sleeping in the next room.

When presented to Titania, it takes Fred a while to convince her he isn’t an infant. Eventually he does, but not before being fitted for a giant diaper. Oberon is a bit more understanding once he hears Fred’s explanation as to what he does for a living. He is soon sent on a mission to the kobolds. They’re the only ones in the land of fairy who can handle iron. The only ones except for Fred, that is. The kobolds are making weapons.

Titania gives him her wand and tells Fred that as long as he doesn’t lose it, his journey will be successful. If he loses it, then he will endure hard times. Of course, Fred loses it.

This results in a series of misadventures that include Fred being turned into a frog and eventually becoming the subject of a prophecy that will restore harmony to the lands of fairy.

The title of the novel has to do with how logic works in this land Fred finds himself in. Human logic isn’t valid here. Ultimately, Fred figures out that the lands of fairy have a logic all their own. Once he figures it out, he’s able to ultimately triumph.

I read the Shea stories about 15 years ago, so my memory is a little fuzzy, but I thought the humor was funnier here. Like the Shea stories, though, I found the humor grew thinner as the story went on. Almost as if the authors couldn’t maintain the joke that long. So they switch over into a problem to be solved wrapped in a travelogue. The result is the book starts out as one type of story and ends up as another.

Of course, humor is very subjective, and I’ve found that I have to be in the right frame of mind for it, at least in written form, so it could just be me.

Lin Carter writes in his introduction that the collaborations between Pratt and de Camp produced work that was unlike what either man produced individually. I tend to agree with this statement in general. I’m not so sure how true it is here.

Other than the occasional short story, I’ve not read de Camp in years. So my memory is a little suspect at this point. That being said, I recall that de Camp’s novels tend to be rather dry. This is, in large part I think, due to the fact that de Camp was an engineer. My memories of his work are that the novels tended to have some idea behind them, the consequences of which de Camp proceeds to work out with rigor. Character and action weren’t the main focus of the stories. This isn’t to say I haven’t enjoyed his work (I have); just that it isn’t the sort of thing you want to read right before bedtime. I think de Camp’s strengths were at the shorter length, Conan pastiches excepted.

I found the ending of Land of Unreason to be a bit rushed, which contributed to my sense of dissatisfaction as the story came to a conclusion. The prophecy, while vaguely alluded to in one or two spots in the first two-thirds, only really becomes important in the last portion of the novel.

The overall impression I had was that de Camp and Pratt were coming up on a word limit and had to cut things short. Considering that John Campbell probably did have some tight word limits for the novels he published in Unknown, that would make sense. The copyright notice in the paperback says that the version published in Unknown was a shorter version. I have to wonder if de Camp expanded it or simply allowed Carter to publish the original manuscript as it existed before Campbell made any editorial changes.

This was an enjoyable novel, especially in the first few chapters where the humor was strongest. The plot seemed to move better than it did in The Blue Star and the hero here is certainly more heroic. Fred not only strives to do the right thing, but he considers the consequences of his actions and who they hurt. This isn’t something every protagonist does. My only real complaint about his heroics is in the fulfillment of the prophecy in the final 40 pages. Fred had it entirely too easy.

Unknown was one of the best fantasy magazine in history. I’m glad Carter reprinted Land of Unreason. While not the best novel to come out of that magazine, it certainly has aged well and is still enjoyable today.

When I began this series, I had the intention of posting about once a month. I’ve not quite hit that, and John has been quite patient when no post has been forthcoming. (Many thanks, sir.) Since next month is October, I’m going to once again break the sequence of novels and skip ahead to something seasonal. I’m not sure what exactly it will be, but I’ll look at something in the vein of Lovecraft.

Join me, won’t you?

Previous posts in this series are:

Lin Carter and the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

The Blue Star by Fletcher Pratt

The King of Elfland’s Daughter by Lord Dunsany

The Wood Beyond the World by William Morris

Lilith by George MacDonald

The Silver Stallion by James Branch Cabell

The Sorcerer’s Ship by Hannes Bok

Deryni Rising by Katherine Kurtz

Keith West blogs way more than any sane person should. His main blog is Adventures Fantastic, which focuses on fantasy and historic fiction.

Hmmm … something seasonal … In addition to the actual Lovecraft, there’s always the anthology Spawn of Cthulhu. Or maybe Hodgson? Either Boats of the “Glen Carrig” or Night Land would fit the bill; “Glen Carrig” is definitely the more accessible of the two.

Great minds must think alike, Joe H. I’m reading one of the Lovecraft volumes now, plus I’m planning on reading Spawn of Cthulhu as well. That’s if John doesn’t mind two BAF posts that close together.

If I may use more space than is usual for a comment — here’s something Dale Nelson wrote about Land of Unreason, for a series about books in C. S. Lewis’s life. “Joy” is Lewis’s American-born wife —

The 1969 catalogue-with-addenda of Lewis’s library included this fantasy, published in 1942 by Holt of New York. So far as I know, Lewis never commented on it. The Lewis library copy might have been Joy’s; according to L. Sprague de Camp in his Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers, Joy had been a member of Fletcher Pratt’s circle. Perhaps Jack never read it, the book being just part of a common library formed after they married and she moved in at the Kilns in 1957. Some of the books in the catalogue, such as Jean Kerr’s Please Don’t Eat the Daisies, don’t seem likely to have been Lewis’s own personal choices!

The story: During the Second World War, American diplomat Fred Barber was relieved of his duties after a serious gaffe, and holed up in a Yorkshire cottage. While his hostess was out, he drank the St. John’s Eve milk she had left for the fairies, and whimsically substituted whisky. Result: a drunken elf takes Barber to the court of Oberon and Titania as a changeling. Barber’s subsequent experiences range from the farcical to, eventually, the straightforwardly adventurous. He encounters a three-eyed sophist and one Noah Fawcett, a Yank farmer with a horse named Federalist. Malacea, a seductive apple-tree spirit, helps a plum-tree spirit steal Titania’s wand from him; Barber journeys across a bewildering landscape of unfixed points of the compass to the cave of the kobolds (who alone of the fairy-peoples can handle iron, and are a threat to Oberon’s realm), and sojourns among the inhabitants of a pool where he fights the totalitarian leech-people of Hirudia, before he recovers the wand. He becomes a frog; later he grows bat-wings. Barber learns that in this Fairyland (unlike that of George MacDonald) even moral laws are different from those of the mortals’ realm. Human legend has it that Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (Red-Beard) sleeps under a mountain, and will awaken when ravens cease to fly around its peak, but Barber doesn’t seem to have heard of this legend, and he certainly doesn’t suspect how his Fairyland experiences will connect with it.

Now, is there any reason to think Lewis read Land of Unreason aside from its presence in his book collection? Certainly he read a great deal of American imaginative fiction, as his essay “On Science Fiction,” for example, indicates. (Incidentally, since he read American pulp science fiction and fantasy magazines, he might have seen it when it appeared in Unknown Worlds in 1941.)

It’s possible that Lewis not only read Land of Unreason but read it in time for it to influence the writing of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (published in 1950), despite Pratt and de Camp’s whimsy and un-Inklingsy ideas about morality. Land of Unreason includes a scene in which men of ice are restored to flesh and blood, and a great marble table splits in two with a crash. Readers of The Lion may wonder if the white marble statues returning to life soon after the Witch’s wintry magic is undone, and the loud breaking of the Stone Table in half, just possibly owe something to the earlier book. Also, in both The Lion and Land of Unreason, a human or humans come from our wartime world into a realm of enchantment and adventurous quest.

A little more from Nelson’s article… I hope this is interesting:

Land of Unreason is one of a bunch of books Lewis owned that were to be reprinted in 1969-1974, when Tolkien’s American paperback publisher, Ballantine, cast about for additional material for the fantasy market. Lewis’s library and the approximately 60 titles of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, edited by Lin Carter, both include William Beckford’s Vathek, five James Branch Cabell books,* Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday, F. Marion Crawford’s Khaled, Roger Lancelyn Green’s From the World’s End (the Ballantine edition was called Double Phoenix and included a work by another author), Rider Haggard and Andrew Lang’s The World’s Desire, Haggard’s The People of the Mist, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land (two volumes as printed in the Ballantine series), George MacDonald’s Phantastes and Lilith (also some shorter MacDonald fantasies, gathered by Lin Carter for a book called Evenor), George Meredith’s The Shaving of Shagpat, Hope Mirrlees’ Lud-in-the-Mist, and William Morris’s The Water of the Wondrous Isles and The Wood Beyond the World. (Interestingly, Morris’s The Well at the World’s End, praised by Lewis, was not in the 1969 catalogue of his library. Perhaps he owned a copy that was later acquired by someone as a keepsake. The Well was reprinted by Ballantine in two volumes.) Also, the Lewis library included eleven titles by Lord Dunsany, an author mined for six Adult Fantasy releases. Richard Hodgens, a member of the New York C. S. Lewis Society, translated a portion of Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso (“Vol. 1: The Ring of Angelica”), the whole of which Lewis read in the original Italian. The Lewis book collection also included fantasy by Mervyn Peake, E. R. Eddison, and David Lindsay that Ballantine reprinted just before the launching of the Adult Fantasy series proper. Lin Carter would have been impressed by Lewis’s collection. Most of the material reprinted in Carter’s series that Lewis did not own belonged to the American Weird Tales magazine tradition (e.g. four volumes of stories by Clark Ashton Smith) or had never been published before (e.g. Sanders Anne Laubenthal’s somewhat Charles Williams-y Excalibur or Joy Chant’s somewhat Lewisian-Tolkienian Red Moon and Black Mountain).

The Lewis library catalogue lists two other books by the co-author of Land of Unreason. The Well of the Unicorn (1948) is listed as by G[eorge]. U. Fletcher – – the pseudonym used for this book by Fletcher Pratt. Pratt’s World of Wonder (1951) is an anthology. Such gatherings of science fiction and fantasy stories were then uncommon publishers’ fare, although the Lewis library included two of the earliest ones, Strange Ports of Call (1948), edited by August Derleth, and Donald A. Wollheim’s Pocket Book of Science Fiction (1943).

*Cabell was an American author of satirical fantasy whose Jurgen (1919) was unsuccessfully prosecuted for copious veiled obscenity. Jurgen was in the Lewis collection, but it is possible that it and the other Cabell books were Joy’s.

The material quoted by me, above, is from the Bulletin of the New York C. S. Lewis Society & the author is happy for it to appear here at Black Gate.

Fascinating stuff! The mind boggles at Lewis owning a bunch of BAF titles, even if not in the actual BAF editions.

> I’m reading one of the Lovecraft volumes now, plus I’m planning on reading Spawn of Cthulhu as well.

> That’s if John doesn’t mind two BAF posts that close together.

Keith,

Not at all!

Here is the link for the Lewis library catalog:

http://www.wheaton.edu/~/media/Files/Centers-and-Institutes/Wade-Center/RR-Docs/Non-archive%20Listings/Lewis_Public_shelf.pdf

Happy browsing!

I should emphasize that Lewis also read books that he did not own.

Finally — my understanding is that J. R. R. Tolkien inventoried his personal library, for insurance purposes, in the 1930s. I hope that the catalogue will be made public.

I didn’t realize that Lewis owned so many titles that became part of the BAF series. I knew he liked George Mac Donald and William Morris because Lin Carter used quotes from Lewis as blurbs on the covers.

Thanks for the quotes, Major.

And, having quickly scanned through the Lewis catalog, the most surprising (to me, at least) title: The Book of Ptath by A.E. van Vogt.

That might be a book that entered the Lewis library when he married Joy Gresham. However, Lewis’s interest in American science fiction dates pretty firmly to the late 1930s. Indeed, I am reasonably confident that one of the things that drew Lewis and Joy together (but you get no sense of this in the “Shadowlands” material) was a shared interest in science fiction.

There is a nice reminiscence, by John Christopher (No Blade of Grass, White Mountains trilogy, etc.) of Lewis and Joy together in Oxford.

http://www.unz.org/Pub/Encounter-1987apr-00041?View=PDFPages

@Major Wootton

That is an EXCELLENT website. I was NOT aware of it. I see many hours wasted in the future because of this!

[…] for the novels, I reviewed The Blue Star here at Black Gate. It was one of the first titles in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. I’ve picked up […]