Romanticism and Fantasy: A Closer Look at William Blake

A few months ago, I started an irregular series of posts about Romanticism and fantasy. I wanted to talk about the significance of Romanticism, the literary movement of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, to the development of fantasy fiction. For a variety of reasons, I’d been distracted from continuing those posts for a while; I want to return to them now. The original inspiration for this series of posts came when I tried writing a piece on William Blake, and realised there was more to be said about Blake’s time and contemporaries than fit into the one post. I’ve since realised that there’s more to be said about Blake himself than I put into the post I wrote, so I’ve decided to return to Romanticism with a longer look at Blake.

A few months ago, I started an irregular series of posts about Romanticism and fantasy. I wanted to talk about the significance of Romanticism, the literary movement of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, to the development of fantasy fiction. For a variety of reasons, I’d been distracted from continuing those posts for a while; I want to return to them now. The original inspiration for this series of posts came when I tried writing a piece on William Blake, and realised there was more to be said about Blake’s time and contemporaries than fit into the one post. I’ve since realised that there’s more to be said about Blake himself than I put into the post I wrote, so I’ve decided to return to Romanticism with a longer look at Blake.

I want to begin by acknowledging a tremendously helpful comment I got on that first Blake post. I spent a fair amount of time in that post considering whether and how Blake should be regarded as a fantasist, and commenter RadiantAbyss pointed out that Blake fit naturally into early fantasy due to his concern with metaphysics. I think that’s a strong point, and something that applies (to a greater or lesser degree) to many of the other Romantic poets. I think it particularly applies to Blake, as I hope much of this post will show.

Before launching into another look at Blake, I want to quickly recap my posts in this series so far, and where I hope to be going with the whole thing. It’s my general contention that modern fantasy (along with science fiction and horror) are deeply linked with Romanticism. I think the writers of that time pioneered approaches and techniques to fantasy still in use today. I wrote an introduction to the series, then talked about the 18th-century background that gave rise to English Romanticism. Then I wrote about the emergence of the Romantic spirit in the late 18th century, starting with the poems of Ossian. I went on to talk about Romanticism and fantasy in France and in Germany before returning to England to discuss Gothic fiction. In those last two posts, I found myself talking about writers consciously trying to mix fantastic elements into a prose form that had been experimenting with greater realism; in other words, trying to find a balance between the real and the fantastic, trying to find a way to present fantasy with verisimilitude. That’s fairly directly relevant to modern prose fantasy, I think. But for this post, and the next two, I’ll be changing my tack slightly, and writing about major poets whose work seems to me to be particularly relevant not only to the genesis of fantasy fiction, but to the themes of fantasy as it is and has been written. And I’ll be starting with William Blake.

“But my memories of that great tragedy are not all sad. There was high adventure, there was noble fighting; and in the end there was — but perhaps you would like to hear about it.”

“But my memories of that great tragedy are not all sad. There was high adventure, there was noble fighting; and in the end there was — but perhaps you would like to hear about it.”

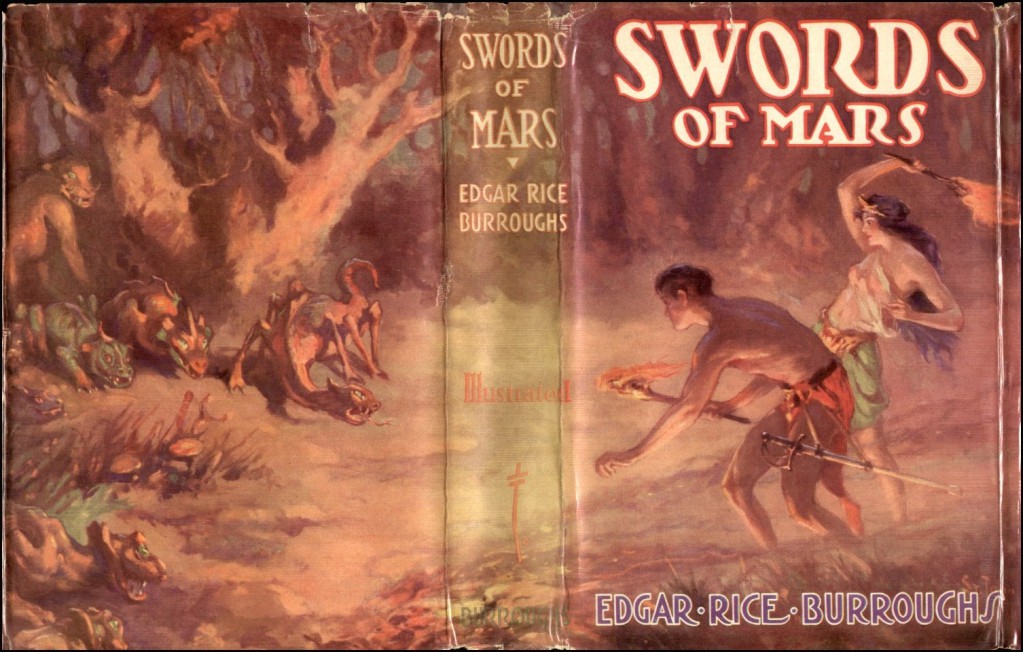

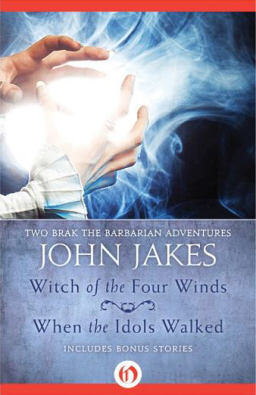

It’s a lot easier for me to be generous about other genres than it used to be. I’m trying to decide if that has something to do with me mellowing with age, or if it’s because there’s a whole lot more sword-and-sorcery available than there was ten years ago … or if it’s simply that I don’t feel shut out anymore now that I’m writing sword-and-sorcery stories for a living.

It’s a lot easier for me to be generous about other genres than it used to be. I’m trying to decide if that has something to do with me mellowing with age, or if it’s because there’s a whole lot more sword-and-sorcery available than there was ten years ago … or if it’s simply that I don’t feel shut out anymore now that I’m writing sword-and-sorcery stories for a living.

The July-August issue of Interzone features new stories by Sean McMullen (”Steamgothic”), Aliette de Bodard (”Ship’s Brother”), David Ira Cleary (”One Day in Time City”), Gareth L. Powell (“Railroad Angel”), and the 2011 James White Award-winning story “Invocation of the Lurker” by C.J. Paget; cover artwork by Ben Baldwin; an interview with Juliet E. Mckenna by Elaine Gallagher; “Ansible Link” genre news and miscellanea by David Langford; “Mutant Popcorn” film reviews by Nick Lowe; “Laser Fodder” DVD/Blu-Ray reviews by Tony Lee; and book reviews by various contributors.

The July-August issue of Interzone features new stories by Sean McMullen (”Steamgothic”), Aliette de Bodard (”Ship’s Brother”), David Ira Cleary (”One Day in Time City”), Gareth L. Powell (“Railroad Angel”), and the 2011 James White Award-winning story “Invocation of the Lurker” by C.J. Paget; cover artwork by Ben Baldwin; an interview with Juliet E. Mckenna by Elaine Gallagher; “Ansible Link” genre news and miscellanea by David Langford; “Mutant Popcorn” film reviews by Nick Lowe; “Laser Fodder” DVD/Blu-Ray reviews by Tony Lee; and book reviews by various contributors.

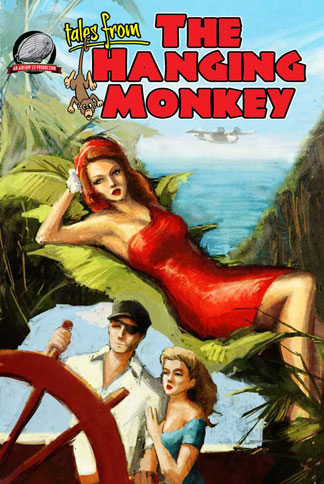

Tales of the Gold Monkey only lasted one season in the early 1980s, but the series has developed a steady cult following in the years since its brief network run. Dismissed as nothing more than an inferior small screen knockoff of the contemporaneous Raiders of the Lost Ark, the series has finally started to earn the recognition denied it at the time. While it took a Hollywood blockbuster to convince network executives to green-light the series, the proposal had been around since the 1970s and the show was conceived, like Raiders, in homage to the serials and classic adventure stories of the past.

Tales of the Gold Monkey only lasted one season in the early 1980s, but the series has developed a steady cult following in the years since its brief network run. Dismissed as nothing more than an inferior small screen knockoff of the contemporaneous Raiders of the Lost Ark, the series has finally started to earn the recognition denied it at the time. While it took a Hollywood blockbuster to convince network executives to green-light the series, the proposal had been around since the 1970s and the show was conceived, like Raiders, in homage to the serials and classic adventure stories of the past.