Dracula: From Script to Screen

Dracula by Bram Stoker frequently vies with The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett as my favorite book.

Dracula by Bram Stoker frequently vies with The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett as my favorite book.

Both stories are archetypes of their genres and despite endless imitations, almost every attempt to emulate the originals falls wide of the margin.

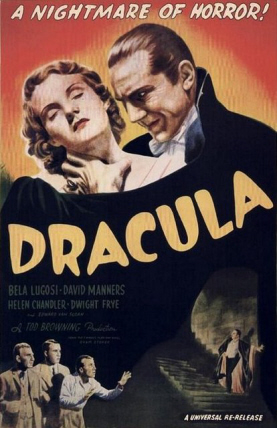

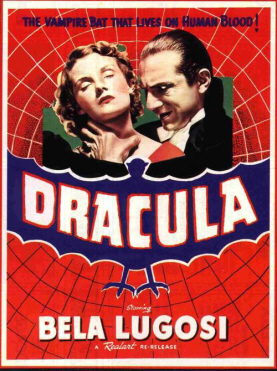

The current vogue for Twilight and its many imitations may be the worst misinterpretation of Stoker’s classic yet, despite its enviable success among pre-pubescent girls (and their emotional equals). The ignorance of most Twilight fans as to how their heroine earned her first name led me to revisit the seminal Universal Horror, Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931) starring Bela Lugosi in an iconic performance that did much to secure Stoker’s novel its hard-won place of acceptance as a literary classic.

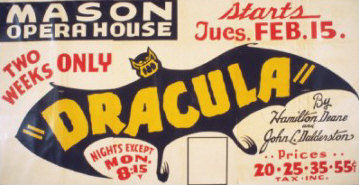

The resulting film owed much to the stage plays which took the West End and Broadway by storm during the Roaring Twenties.

Film historian David Skal has gifted the world with several excellent books and DVD bonus features and commentaries chronicling this once untapped goldmine’s transition from page to stage to screen.

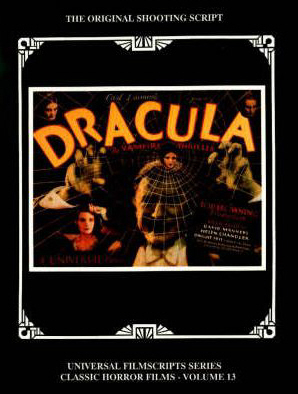

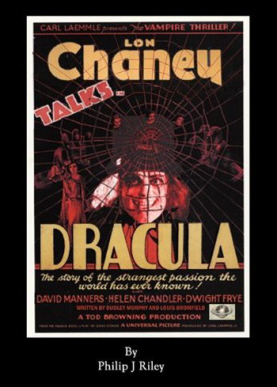

Film buff Philip J. Riley has done one better (actually twice better) by sharing with film lovers not one, but two volumes collecting the various story treatments and screenplay drafts that were languishing in Universal’s files for decades.

MagicImage Filmbooks brought Dracula: The Original 1931 Shooting Script, the first of Riley’s Dracula tomes to print in 1990, and BearManor Media followed suit with the newly-published essential companion volume twenty years later: Dracula Starring Lon Chaney – An Alternate History for Classic Film Monsters.

It remains all too infrequent that screenplays see print in book form the way their theatrical counterparts from the legitimate stage do, and it is only the most cherished of literary classics that see earlier drafts and author’s notes published.

It remains all too infrequent that screenplays see print in book form the way their theatrical counterparts from the legitimate stage do, and it is only the most cherished of literary classics that see earlier drafts and author’s notes published.

It is this fact that makes Riley’s scholarship, dedication, and most of all generosity in making these scripts accessible an absolutely priceless treasure.

Riley’s series of film books are essential to anyone who appreciates the fact that movies without the benefit of literate writers would be…well…vapid summer blockbusters.

The stage adaptations of the twenties made many changes to Stoker’s book. Interestingly, few of these were present early on in the film’s development. Bela Lugosi was setting attendance records on Broadway and yet, initially Universal planned the film as a vehicle for either Lon Chaney or Conrad Veidt.

Hamilton Deane’s 1924 stage play removed Transylvania as a setting for the first part of the story, eliminated all but six of the book’s major characters, and cast Professor Van Helsing as a scientist specializing in obscure diseases rather than Dracula’s Old World counterpart with a knowledge of religion and the occult that were absolutely foreign to Edwardian England.

Most importantly, the repulsive, Satanic vampire count of Stoker’s novel was transformed into a suave Continental gentleman in the Valentino mould.

John L. Balderston’s 1927 Broadway adaptation removed even more characters, altered key relationships (such as turning Dr. Seward from Lucy’s suitor to her father), and placed Dracula in the basement of Seward’s sanitarium, thereby eliminating his need to purchase a home in England in the first place.

John L. Balderston’s 1927 Broadway adaptation removed even more characters, altered key relationships (such as turning Dr. Seward from Lucy’s suitor to her father), and placed Dracula in the basement of Seward’s sanitarium, thereby eliminating his need to purchase a home in England in the first place.

Balderston added a great deal of comic relief by playing the lunatic Renfield for laughs and adding a Cockney minder, Butterworth, to form a dimwitted double act with the lovable fly-eater.

Despite the success of the stage plays, it is hard to accept their artistic merit today outside of star-making performances by Lugosi and Edward Van Sloan (both of whom would reprise their roles for Universal’s film version).

Fritz Stephani authored the first treatment for Universal in June 1930. Stephani is best remembered for his work adapting Alex Raymond’s classic sci-fi comic strip Flash Gordon into a cliffhanger serial for Universal in 1936.

Stephani’s natural affinity for such material is present in his Dracula treatment in the form of a campy bat plane that Dracula pilots from Transylvania to London. One wonders if Bob Kane got his hands on this treatment before creating Batman a few years later.

However, Stephani is surprisingly faithful to Stoker in most aspects, even retaining Stoker’s climactic return to Transylvania for the final act.

One bit of ingenuity in Stephani’s script has Dracula impaled on the broken spokes of a stagecoach wheel during the final battle.

One bit of ingenuity in Stephani’s script has Dracula impaled on the broken spokes of a stagecoach wheel during the final battle.

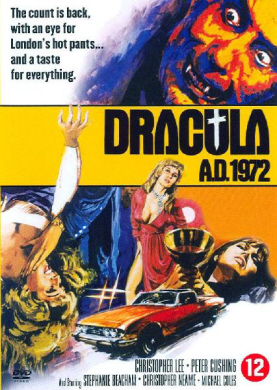

This innovative idea would eventually be utilized by Hammer films in Dracula AD 1972 – a rare moment in that latterday Hammer horror where the talents of Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing were not squandered.

Louis Bromfield’s July 1930 screenplay draft, while well-written, makes a muddle of things from the start by making Englishman Jonathan Harker a Catholic, and having him so well-versed in his faith that he utters exorcism prayers to calm the wind in Transylvania.

Obviously, Bromfield failed to grasp that introducing a surrogate exorcist in the opening scene would have rendered Dracula ineffectual.

Once the storyline moves to England, Bromfield makes matters worse by introducing an overweight comic relief socialite, Mrs. Triplett (think Margaret Dumont without the wit and timing).

Surprisingly, Bromfield was still supportive of retaining Stoker’s original ending, although the stage play’s influence on the London scenes can be detected.

Surprisingly, Bromfield was still supportive of retaining Stoker’s original ending, although the stage play’s influence on the London scenes can be detected.

Dudley Murphy’s August 1930 rewrite is really the most fascinating of the early drafts. Despite not receiving screen credit on the eventual film, a surprising amount of the classic dialogue and scenes in the 1931 film originate with Murphy’s draft.

Things do start off oddly with a highly original opening depicting a vampire epidemic baffling the medical communities of Europe.

The purely scientific Van Helsing (by way of Hamilton Deane’s play) is established in these scenes, as are most of are supporting players at Dr. Seward’s sanitarium. Martin, Renfield’s comic relief attendant (re-named from Balderston’s Butterworth character) is introduced here as well.

The action then shifts belatedly to Transylvania (Murphy failed to appreciate the benefit of starting off with the eerie Old World and then bringing the menace to the familiar modern setting) with an extended role for Sara (reduced to a comic relief cameo in the opening scene of the final film) and a rewritten Mrs. Triplett (rendered as a painful menopausal slapstick character) before finally bringing Harker to Castle Dracula.

The final shooting script from September 1930 is credited solely to Garrett Fort, although director Tod Browning and (especially) Dudley Murphy deserved co-writing credits (and had them on the original typed cover page to the script).

This is surprisingly close to the finished film, right down to having the reader’s interest quickly wane after the atmospheric Transylvanian opening. The pitch is perfect for the first act and it’s a pity that one more draft was not completed to strengthen the remainder.

This is surprisingly close to the finished film, right down to having the reader’s interest quickly wane after the atmospheric Transylvanian opening. The pitch is perfect for the first act and it’s a pity that one more draft was not completed to strengthen the remainder.

One benefit of reading the screenplay is seeing what was intended, but deleted due to time or budgetary constraints. As DVD viewers well know, deleted scenes fall into two extremes of quality and the script offers both.

On the one hand, the staking of Lucy (faithfully re-created from the novel) is one of the glaring plot-holes in the finished film that is happily restored in the script.

On the other hand, learning that the genuinely sinister scene in which Renfield crawls towards the unconscious maid originally revealed the object of his attraction was the fly that landed on her makes one appreciate the film’s abrupt cutaway.

Nonetheless, Philip J. Riley and his publishers have given film buffs and horror aficionados a series of titles that not only preserve the art of screenwriting, but provide full documentation of the development of a pop culture icon.

Highly recommended.

William Patrick Maynard was authorized to continue Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu thrillers beginning with 2009’s The Terror of Fu Manchu, published by Black Coat Press. He is currently working on a sequel, The Destiny of Fu Manchu as well as The Occult Case Book of Sherlock Holmes. To see additional articles by William, visit his blog at www.SetiSays.blogspot.com.

Dracula (1931): Cast/Crew

Cast:

Count Dracula – Lon Chaney Sr.

Abraham Van Helsing – Lon Chaney Sr.

Jonathan Harker – Lew Ayres

John Seward – Herbert Bunston

Martin – Charles Gerrard

Hawkins – Halliwell Hobbes

Mina Harker – Bette Davis

Lucy Harker – Mae Clarke

Renfield – Bernard Jukes

Ms. Triplett – Margret Dumont

Nurse Briggs – Moon Carroll

Sara – Carla Laemmle

Harbormaster (Voice) – Tod Browning

Dracula’s Bride #1 – Geraldine Dvorak

Dracula’s Bride #2 – Cornelia Thaw

Dracula’s Bride #3 – Dorothy Tree

Crew:

Directed By Tod Browning

Produced By Carl Laemmle Jr. & Carl Laemmle

Screenplay By Louis Bromfield, Fritz Stephani, Dudley Murphy, Louis Stevens & Garrett Fort

Based On “Dracula” By Bram Stoker

Director Of Photography: Karl Freund

Editor: Maurice Pivar

Filming Dates:

9/29/1930-1/2/1931

Release Date:

2/13/1931 (USA)

Production Companies:

Universal Pictures

Distributor:

Universal Pictures (1931) (USA) (Theatrical)