Special Fiction Feature: “The Whoremaster of Pald”

By Harry James Connolly

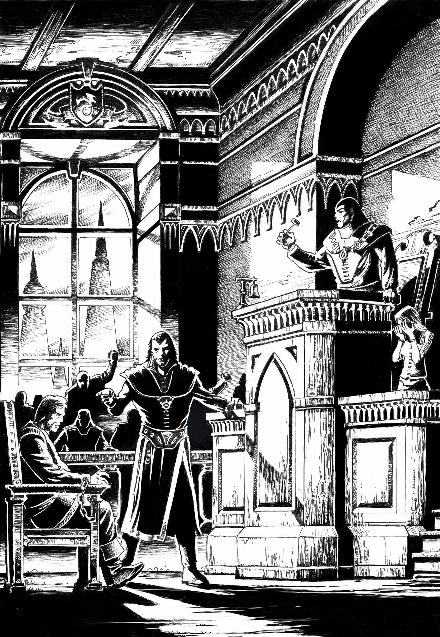

Illustrated by Chris Pepper

This is a Special Presentation of a complete work of fiction which originally appeared in Black Gate 2. It appears with the permission of Harry James Connolly and New Epoch Press, and may not be reproduced in whole or in part. All rights reserved. Copyright 2001 by New Epoch Press.

My prison cell stank like a bird cage. It was terribly dark, and I listened for the sound of rats. I despise rats. I lay down on the wooden plank that would serve as my bed for the night. My bruised back throbbed, but at least I could still breathe. It’s always nice to breathe after a beating.

My prison cell stank like a bird cage. It was terribly dark, and I listened for the sound of rats. I despise rats. I lay down on the wooden plank that would serve as my bed for the night. My bruised back throbbed, but at least I could still breathe. It’s always nice to breathe after a beating.

In the morning a sweet little sparrow of a girl would testify against me. The charge was murder, and she had seen me do it. It had started only the evening before, when I decided that something had to be done about the new Warden.

Something had to be done about the new Warden.

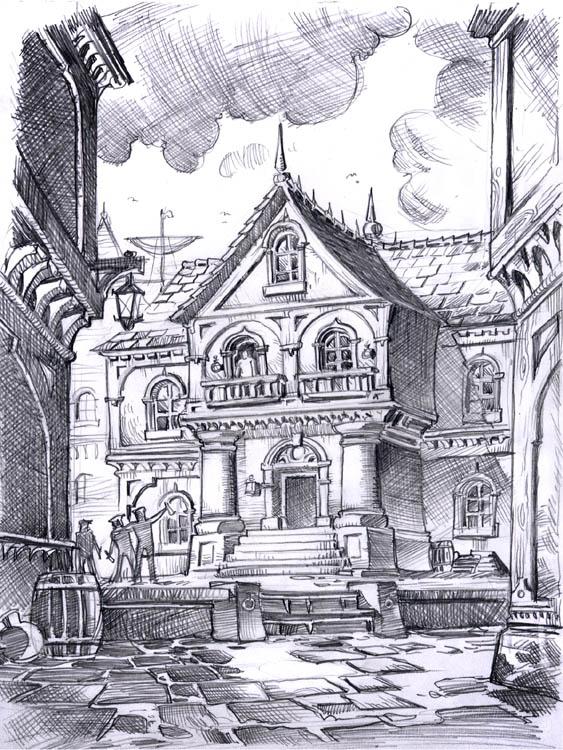

I stood alone on the veranda, surveying the Street all the way down to the docks. I saw no musicians. No actors. No mimes. The Quarter lay empty, except for a trio of Tilpic sailors staggering along the gutter. They sang in their own language, their voices clear, the song indecipherable. Their performance would have scandalized the respectable citizens of Pald, but on this side of the Wall, in the Foreign Quarter, attitudes were more permissive. Or they were supposed to be.

Public performance was illegal in Pald, of course, but the law was not normally enforced on the Street. The Foreign Quarter was famous for its diverse music, foods and women. Or it was, before the new Warden arrived.

He was a problem. A dangerous problem. I had to solve him.

As usual, the Tilpics walked up one side of the Street and would soon walk down the other, searching for a whorehouse they could afford. I displayed my prices on the front post to discourage such riffraff, of course. Still, I liked their voices. The Quarter could be quite gloomy without music.

Then the Public Men appeared, carrying those silly halberds strung with yellow streamers. The Tilpics laughed at the ribbons, and the Men laid their hands on their truncheons. There was no fight. After a few words, the Tilpics bowed and silently crossed the Street. One paused to read my prices, but his fellows dragged him away.

I wiped a smudge from the red glass of my lamp and stepped inside. A Tilpic captain, maybe commander to those musical sailors, sat at the bar. All the other customers were upstanding Paldan men, aging merchants and dissolute nobles who dared the Quarter for pleasures forbidden in other parts of Pald.

And we were only half full.

The Tilpic captain saw me and approached, iron-banded hat in one hand, drink in the other. He displayed his brown teeth.

“Captain Onsooloc!” I said. “It has been too long, sir.”

“Zed, it has been a mere six months, my friend.”

“If you would permit me to disagree, it has been eight months. You were last here during the Clock Festival.”

“Ah, Zed, your good memory honors me. But tell me, why is there no music tonight? No dancing? The streets are a somber as an old maid’s bedtime.”

A pastry flew across the room and struck the Captain’s shoulder. “Because, you sweating clown,” a man announced, “we do not prance around like a pack of Tilpic idiots!”

Onsooloc and I turned together. Jugun emerged from a corner booth, a second pastry in hand. He stepped toward the middle of the floor, thick arms across his broad belly. “Why don’t you put on that hat, clown, and dance a jig for us.”

Onsooloc lifted his collar and examined the jelly stain there. His face grew calm and he laid his hand upon his sword.

I stepped in front of him. “Captain Onsooloc, I do not believe you have met Jugun, the mayor’s nephew.”

“He will soon be a mound of soil in the mayor’s garden. Step aside, my friend.”

“I am not quite sure you are aware that any injury, however minor, to the mayor’s nephew would send you to the gibbet…”

“… Honor demands…”

“… And your entire crew would join you. As, I am afraid, would I.”

Onsooloc’s hand fell away from his sword. “Is it true?”

“I am sorry, but as proprietor, I am culpable for any crime committed here. May I offer you something for your inconvenience? Perhaps an evening in the Sunset Room with Banu? She just arrived from the provinces; you would be her first client.”

Onsooloc clapped my shoulder and laughed. “To sacrifice my life for my honor — Fft! It is nothing. But to sacrifice yours, or my crew… Well, it seems I must endure.”

“Thank you, my good captain.” I nodded to Aneek. Pitcher in hand, she hurried toward Jugun.

“A new girl, eh?” The captain winked as he walked toward the stairs. “You would not lie to me?”

I widened my eyes and laid my fingers on my throat. “Good sir, I would not dare.” Onsooloc laughed again and went upstairs.

Aneek poured a cup of wine for Jugun. He gulped it and flashed a contemptuous smile toward me before flopping back onto his couch. Something in that smile made me nervous.

Aneek followed me into the waiting room. Six girls lingered there, applying makeup or nibbling at their dinners. Banu sat alone, a plate of chopped egg untouched in her lap. She was three years past her Paldan marriage day; I refused to hire girls younger than that. But she had yet to prove she was ready to work the rooms upstairs. “Banu,” I said, “it’s time.”

She set her plate on the table and walked toward me like a bird summoned by a serpent. Aneek scowled. “Come,” she barked. “It’s not as bad as all that.”

I took Banu’s elbow. “Do you want to change your mind?”

Her face lit up. “May I?”

“Of course, my dear. You are not a slave. You may quit any time.” Aneek frowned and drummed her fingers on her elbow. Banu stared at the floor.

“I will go.” Her voice cracked as she said it.

“Captain Onsooloc is a Tilpic gentleman. If you are nervous, tell him. He will be kind.”

Banu climbed the stairs, bare feet whispering on the carpet. I exchanged pleasantries with the other girls and went back into the main room. Aneek followed.

“You gave Jugun a drink from the green pitcher?” I asked.

“His third. He should be snoring in the corner.” He wasn’t. He was leaning across a table murmuring to one of the girls. Whatever he was saying, she didn’t like it.

The delicate frown lines around Aneek’s mouth seemed especially pronounced. “Is something wrong, my dear?”

She glowered at me. “Pereek is leaving at the end of the tenday. She’s our best girl! I keep telling you, you pay them too much. They build their nest eggs in a few months and they’re gone. If you’d pay a few apes less…”

“… We’d have a less enthusiastic staff. It isn’t as though we’re running low on applicants. This is, after all, Pald.”

Aneek scowled and stalked behind the bar. Irritated with me again. She had stopped working in the rooms upstairs ten years ago, and I still wasn’t sure why she’d stayed on.

I approached the Chief Magistrate’s table and complimented the man’s rather garish sash. He had barely opened his mouth to reply when Jugun shouted my name. I excused myself, motioned to Aneek to refill the man’s cup, and approached Jugun’s booth.

“Good evening, sir. Always a delight to see you in my humble establishment.” I glanced into Jugun’s cup. Empty. The green pitcher had never failed to quell an unruly customer before, not after three doses. “May I refresh your drink?”

“No, boy, you may not.” Jugun was at least 15 years my junior, but I let it pass. “Bring me a pot of kepple.”

“I regret that we do not serve kepple here.”

“Well go out and get some, dunce.” His voice was slurred.

“I’m sorry, but selling kepple violates house rules. There are other establishments in the Foreign Quarter, I am told…”

Jugun lunged out of the booth. I yelped and backed away. The man was tall, his arms thick from hours in the dueling yards. Food and drink had already swollen his belly, and eventually he would be too vitiated to threaten anyone, but that happy day was far in the future. “You Jallaran scum, don’t talk to me about rules.”

“It is also against Paldan law.”

“Law? My uncle is the law.” Jugun reached up and grabbed a delicate crystal luster from the chandelier. He held it as though he might pluck it, like fruit from a tree. Years of kepple use had stained his thumb and index finger gray. “I could have you shut down by morning. Is that what you want?”

It wasn’t. “No, sir. Please. I am, of course, aware, like the rest of the city, that you are a man of great influence. I will certainly do everything in my power to serve you. Aneek!”

Jugun poked me. His thick finger sank into my over-plump belly. “No. You do it. Keeping me happy is no job for a servant. When I say get something, you get it yourself.”

I stepped back and bowed. “You are, as always, right, sir. Someone of such elevated stature as yourself deserves only my most abject service, and I was a fool not to realize it.”

“You are a Jallaran fool. Say it.”

Jugun was often rude, but never this outrageously. “Well, since my family is from Jallarel, what other kind of fool could I be?” I twittered nervously and wrung my hands over my belly, a womanly gesture in Pald. Jugun sneered and retreated as if I’d suddenly transformed into a leper.

Everyone in the room was scowling. One man stood, dropped a pair of gold apes on the table and walked out. Paldan men couldn’t stand the sight of humiliation.

I hurried into the kitchen. The cooks had also decided not to look at me. Aneek banged into the room. “Zed! How could you let him treat you that way! That dog! I’ll pour so much green pitcher in him he’ll never wake up!”

“No,” I said, “no more green pitcher. If he dies we’ll be in terrible trouble. Pour him a glass of red pitcher and keep him happy. Something is happening tonight.” I pulled on my coat and left by the kitchen door.

The Street was empty. Normally, there would be crowds swarming around jugglers, mimes, dancers, mock duelists and musicians. Instead, I passed a lone stall offering spiced wine and skewers of “pork.” This quietude would never draw the crowds I needed to run my business. I nodded to a trio of Public Men as I walked by. Bored, they leaned on their halberds and scowled. Everyone scowled at me that night.

The Street was empty. Normally, there would be crowds swarming around jugglers, mimes, dancers, mock duelists and musicians. Instead, I passed a lone stall offering spiced wine and skewers of “pork.” This quietude would never draw the crowds I needed to run my business. I nodded to a trio of Public Men as I walked by. Bored, they leaned on their halberds and scowled. Everyone scowled at me that night.

The farther I walked toward the docks, the seedier the establishments became. Shadowy figures lurked in alleys or crouched in trash heaps. Somewhere nearby, a man begged his son to stop beating him. I stayed within the glow of the oil lamps.

Two men stepped out of the shadows. “Hello, Wiskik,” I said. “How is the Foreign Merchants Association lately?”

“Slow,” he answered. It was an answer that described many things about Wiskik, but he wasn’t employed for his brains. He extended a meaty paw. “So give it here.”

This game again. “Why certainly.” I surrendered my purse. “Have you a receipt? I must have one for the Public Examiner.” Wiskik only snorted; I shrugged. “I shall stop by Bilby’s office, then, and get a receipt for 33 double apes, collected by his trusted lieutenant, Wiskik.”

He drew a knife. “No you won’t.”

“I’m sure Bilby will be impressed with your initiative, sir, especially since he collects so little from me each month.” Which was the exact opposite of the truth. Wiskik was employed to shake down street beggars and mimes, not businessmen like me. And if I was killed, Bilby would lose my rather large monthly payments.

Wiskik dropped the purse into the gutter. I picked it up. I do not mind stooping for money, even my own. “Terribly kind of you to let me pay at the usual time. Good day, gentlemen.”

I walked a short distance further to a whorehouse with mud flaking off the lintel and urine stains on the sills. I entered.

The smell of sweaty feet assailed me. The owner of the house flavored his meals with Lisk spices, which have often been compared to dirty human flesh. According to local gossip, they were a perfect compliment to the stewing meats he employed.

The hostess, a dingy woman with missing teeth and gray fingers, recognized me at once. She gave me the worst booth in the room. To sit down, I had to shove aside one of the Tilpic sailors I’d seen earlier, now without shoes or scarf. The booth had a broken seat, and customers had half-filled the opening with rotten food, kepple sludge and spit. I hoped the patterns on my waistcoat would disguise any stains I might pick up.

The proprietor, a Lisk named Sansunus, slid into the booth as if his limbs had been freshly oiled. “Pleasant midnight to you, Jallaran. Have you considered my offer? Two thousand apes is a tidy sum for that small house of yours.”

I smiled. My wardrobe alone was worth two thousand. “Prosperity to you, Lisk. I believe your hostess told you why I have come.”

Sansunus grinned. The fingers of both his hands were stained as gray as a storm cloud, and his pale, pustule-ridden face gleamed with sweat. He wore an elaborate cravat, and I wondered if it was really enchanted, as rumors suggested. All magic was outlawed in Pald, especially Lisk embroidery.

He produced a stoppered brass pot and named an exorbitant price. It was not as high as I had expected. I asked to conduct business in the back room, but he waved away my concerns. I paid.

Neither Sansunus nor his hostess escorted me to the door. The latter was unlacing the gloves of the Tilpic sailor, and the former stared at me like a starving man about to be fed.

Once outside, the air of the alleys and docks seemed positively fragrant. I lifted the pot and stared at it. My instincts jangled. I could not get the Lisk’s hungry expression out of my mind. Something was happening, and if I did not wake up to it soon, I was headed for terrible trouble.

Then I remembered Jugun’s insistence that I run this illegal errand personally, and his contemptuous grin. I was being set up. If only I had realized that before giving Sansunus my money.

Three men lurched out of an alley, but slipped back once they recognized me. I was, after all, paying a tidy sum to be protected by the Foreign Merchants Association. Matching gazes with the man I took to be the leader, I set the pot on the cobblestones and walked away. That much kepple would fill their cups for a tenday, if they didn’t use it themselves.

I soon approached home. Several newly-arrived Public Men lounged near, but not too near, my front stair. I draped my handkerchief over my hand, as though hiding something from them.

I soon approached home. Several newly-arrived Public Men lounged near, but not too near, my front stair. I draped my handkerchief over my hand, as though hiding something from them.

I nodded to the Men; they pretended not to notice. At the back door I found three more leaning against the alley wall, awkwardly refusing to look at me. I climbed the back stairs and, within minutes, entered the main room with a new brass pot from my own kitchen in hand. It was covered with my handkerchief.

The new Warden stood at the bar with three of his Men, including Lodol, who had been First Man in the Foreign Quarter for a good dozen years. I tried to nod at them and hurry by, but Lodol grabbed my arm with a gloved hand.

I smiled for them. “Welcome, gentlemen. Always a pleasure to serve the Warden and his Public Men. I will be with you as soon as I see to a customer.”

The Warden blocked my way. He was not a robust man, but the strength of will evident in his expression was quite menacing.

“Prosperity to you, chosen one,” he said, in Jallaran.

“And to you, sir,” I responded, but in Paldan. “You honor me with my own language and its proper forms, but I am afraid that I have spent the whole of my life in this fine city, and you seem to have the advantage over me with that lovely language. How did you ever come to learn it?”

“I served in the Ape Head Bay campaign,” The Warden said, staring at me as if I was a stain about to be wiped away, “and had cause to interrogate many Jallaran prisoners.”

“Brrr! It gives me chills just to hear you say it!”

“It may give you more than a chill,” Lodol said, lifting the pot in my hand.

“What have we here? Kepple?” He tore away the concealing towel.

“Kepple?” I said. “This is a pot of bobo nuts with honey and hot pepper, from my own kitchen. Kepple is illegal, First Man Lodol, as you well know.”

The Warden and First Man looked toward Jugun. He stood by his booth, a smug grin on his face. “Excuse me,” the Warden said, and walked toward him.

“Our new Warden seems an upright fellow,” I said. Lodol snorted. I lowered my voice. “But I am surprised that you yourself have not won the appointment after so many years of, if I may say so, excellent service.”

“Pfft. I’m no soldier. I have no political aspirations. I’m just a man who does his job. This new fellow won’t be here long, though. He’s got some sense.”

Which meant the new Warden was letting Lodol show him the ropes. Capable Wardens were promoted out of the job within a tenmonth, while lazy or incompetent men could languish for years.

Jugun frowned, then sneered. Whatever the Warden said to him, the mayor’s nephew did not like it. He then emphasized that dislike by grabbing a fistful of the Warden’s sash.

“Excuse me,” Lodol said.

I slipped into the waiting room, where Aneek stood twisting a dishrag in her fists. “What happened? Are you under arrest?”

“No, my dear.” I took the dishrag, shook it out and folded it. “The Public Men seem to think I serve kepple, which I do not do. As for what is happening, the mayor’s nephew is trying to ruin me.”

“Why?”

“An interesting question. Almost as interesting as what this young girl is doing here instead of the Sunset Room?”

I nodded toward Banu, who stood in the corner like a scolded stepchild. “She backed out, of course,” Aneek said, “just as I said she would. I sent Jentel and Jesta in her place.”

Banu stared at the floor. “I’m sorry. I feel terrible…”

“… Nonsense.” I lifted her chin. “I said you could change your mind, and I meant it.” Aneek glared at the ceiling. Later, I’d hear another lecture about spoiling the girls.

But she didn’t understand. Even now, eight of my girls were lounging around us, watching out of the corners of their eyes. If I tried to force Banu, or anyone, to do anything, I’d have an empty house by the end of the tenday. Besides, who wants an unwilling whore? “We always have other work around here, if you want it,” I continued. “Or would you rather go home?”

“Home, sir. Thank you.”

“Aneek, offer a red pitcher to any guests that have not abandoned us…”

“Shut up.” The slurred voice came from behind me. “You didn’t do what I told you to do, so I’m taking her.” Jugun shoved me aside, reached out with one massive hand and clamped onto Banu’s broomstick arm. He pulled her through the door.

I slipped between them and the stairs. “Sir, one moment. This is our laundress. She does not work the rooms.”

Pereek, bless her, spoke up. “I can take her place.”

Banu stared at Jugun with wide, terrified eyes. “Shut up,” Jugun said, sticking a thick gray finger in my face. “Get out of the way, or this…” He threw something that shattered on the floor. “… Will happen to you.” Judging by the shards, he had just smashed a pendant from the chandelier in the main room.

I normally wouldn’t allow anyone to take a girl against her will, but I couldn’t give Jugun an excuse to close my house, either. Really, what choice did I have?

I sighed loudly. “Aneek, show them to the Crimson Room, please. I will bring up a pitcher and refreshments in a moment.”

She blinked at me, astonished, then rushed ahead. Jugun followed, dragging the girl after him.

I stepped into the waiting room and prepared a green pitcher and a plate of hearth crackers. The staff watched, their painted lips pressed tightly together. I hoped I would have the chance to explain why I had to do what I was about to do, and that they would still be around to listen.

I peeked into the main room. The Warden sat at one table, and the Chief Magistrate at another. They were the room’s only occupants, and after all the unpleasantness of the evening, I would probably have to cancel the Honorable Magistrate’s bill.

This mess was costing me a fortune.

I climbed the stairs and padded down the hall. The few occupied rooms were quiet. Privacy was part of the service. I knocked on the door of the Crimson Room. Aneek let me in.

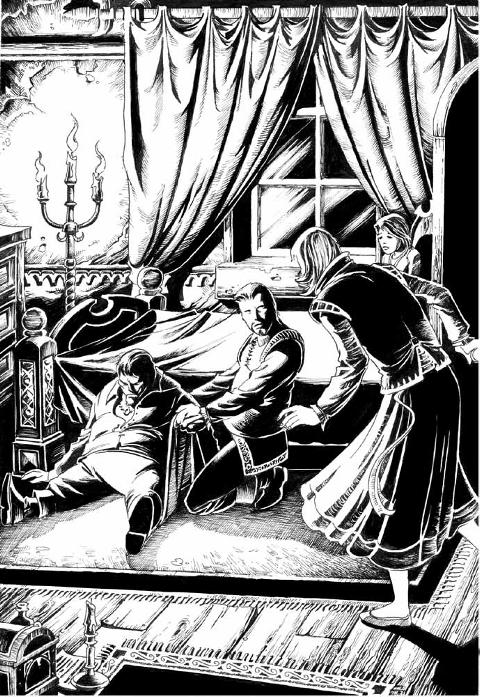

Jugun stood by the bed. He had tossed his sash onto the red coverlet, and was unlacing his shirt. Banu trembled beside the heavy scarlet drapes, silent tears streaming down her face. Aneek studied my expression, wondering what I would do.

I nodded to her. “Thank you, Aneek.” She left. “Sir, I have brought you a splash of wine and a few crackers.” I set them on the end table. “May I hang your shirt in the…”

“Quiet,” Jugun said. “Stand there. You’re going to watch me, and I’ll show you how a man should handle a woman.” Then, with the arrogance of a sword-school bully, he turned his back.

I drew my sleeve knife, said “Why thank you, sir,” and plunged the blade through the back of his neck into his brain.

The strike was neatly done. Jugun turned to rubber in an instant, and I threw a shoulder into him as he crumpled, knocking him onto the bed. I bunched the bed sheets around the wound; it was one thing to wash blood out of covers, another thing entirely when it came to carpets.

Banu drew a huge breath. I pointed at her and said, “Don’t scream!” I then realized I had pointed with the bloody knife. She blanched and fell into a chair, staring at the blade. At least she was quiet.

Banu drew a huge breath. I pointed at her and said, “Don’t scream!” I then realized I had pointed with the bloody knife. She blanched and fell into a chair, staring at the blade. At least she was quiet.

Jallaran sleeve knives have a cloth fringe around the hilt, to prevent spatters of blood on the wielder’s clothing. My sleeve was clean, as far as I could tell. I tossed the knife into the sheets and wrapped up the corpse.

I rang the service bell. Banu had begun to tremble. “My dear, this might seem harsh to someone as delicate as you, but I didn’t have a choice. I couldn’t let him attack you, could I? Besides, he broke a pendant from my chandelier. My grandfather made that chandelier with his own hands, and carried it here all the way from Ape Head Bay.”

I noticed a bulge in Jugun’s boot pouch. I opened the flap and a tiny bean bag fell onto the floor. It was clumsily stitched, with tassels at the corners. I picked it up.

Self-loathing crashed over me like a wave. Suddenly, I needed the knife again. I dug it out of the sheet and pressed the bloody tip against my belly. I’d just killed a Paldan. I was bound for the gibbet, where murderous, whore-selling scum like me belonged. Better a quick thrust into my poisonous heart —

My hands jolted open, and I threw the bag and the knife to the floor. I had wanted to kill myself out of pure self-loathing, because of that little bag. It was filled with rage and hatred, and it was all aimed at me.

Magic. I grabbed the fire tongs and rolled it under the bed.

The door opened and Aneek entered. “River of stars!” she said. “You really did it.” She kicked Jugun in the groin with all her strength.

“There will be time enough for that later, my dear. Right now we have a dead body in our house and a front room full of Public Men. Get the harness from the closet, if you please.”

“River of stars,” Banu said. “River of stars, river of stars, river of stars.”

“You could at least help,” Aneek snapped. She opened a hidden panel, drew out a rope and set it on the service cart. Holding the sheet, Aneek and I hoisted the body onto the cart. We wheeled over to the laundry chute, which was larger in this room than in any other for just this purpose. Not that we use it. Much. Aneek looped the rope around Jugun’s chest.

“Dispose of him in the usual way?”

I met her eye. “Yes. I’ll pull the carriage around the back and dump him by the docks.”

Aneek stared at me, and for a moment I was afraid she’d say That’s not the usual way. Then her gaze darted toward Banu, and she understood. “Oh. Right. The carriage.”

We eased his feet into the chute, then lowered the body all the way to the basement. My back and shoulders strained under the exertion, and I almost dropped the rope. What would the new Warden have done if he heard a corpse falling through the walls? I once again resolved to exercise regularly.

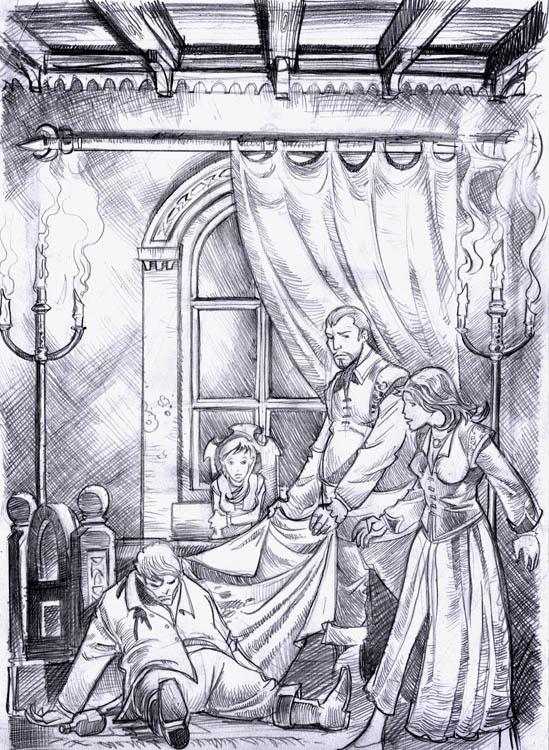

I gestured toward the table and Aneek brought a cup. I filled it from the green pitcher. Aneek lifted it to her mouth, but I stopped her. “I brought that up here for Banu.”

Aneek stripped the bed and threw the covers down the chute. I knelt beside the girl and placed the cup in her hand. She shrank from me. “You don’t have to fear me, my child. I’m here to watch over you. Drink this. It will make you feel better.”

Aneek stripped the bed and threw the covers down the chute. I knelt beside the girl and placed the cup in her hand. She shrank from me. “You don’t have to fear me, my child. I’m here to watch over you. Drink this. It will make you feel better.”

She stared into the cup. “Poison?”

“What? Of course not, my dear. Why would I?”

“Because,” she said, on the verge of tears again, “I saw what you did.”

“It’s true,” Aneek agreed, making the bed without looking at us. “She could put a rope around both our necks.”

“All life is risk. Tell me, Banu: Why would I save you only to kill you?”

She thought a moment, then gulped down the contents of the cup. “What if someone asks what happened tonight? What do I say?”

“It’s simple. Jugun was drunk when he dragged you up here, which is true. He fell asleep before he could harm you, which is almost true. Out of fear, you waited several hours before leaving, which will also be true.”

Banu’s eyelids began to droop. “It’s Lisk stitch magic.”

I led her to the bed. “What’s that, my dear?”

“That bag in his pocket, the one you threw under the bed. The symbol on the top is hatred, and your name spelled in Lisk.” Her feet slid along the carpet, and her chin dipped toward her collar. “The thread binds you…” Her voice trailed off. Aneek threw back the clean coverlet and I eased the girl onto the mattress. We tucked her in. Banu puckered her lips, then began snoring loudly.

“Is this what she was talking about?” Aneek asked as she reached under the bed.

“Don’t!” I lunged for her but she backed away, her face twisting with hatred. She clutched the bag in her fist and darted toward the door. I caught her and ripped the bag from her grasp.

She sagged in my arms. “Zed — Zedekapriam, I wanted to tell the Warden about Jugun. I wanted to send you to the gibbet!”

I took the fireplace tongs again and lifted the bag. “It isn’t your fault, my dear. I’ve heard of stitch magic, but never seen the real thing. See how the symbol for hatred is sewn with the same thread that spells my name? Whoever carries it feels a loathing inextricably ‘tied’ to me, as it were. Interesting.” I dropped it down the laundry chute.

“What about her?” Aneek said. “She can’t be trusted, Zed. Do you really expect her to lie to a bully like Lodol?”

I opened the door and ushered her into the hall. “My dear, have some faith in me. I know what I’m doing.”

We passed the Magistrate in the hall. Pereek walked beside him. I bowed to them, and she winked at me. Pearls in the sky, she would be hard to replace, no matter what I’d told Aneek.

Which left only the Warden in the front room. He sat in a booth, staring at the empty air. I approached him, hands clasped. “Can I get you something, sir? Cup of wine? Platter of oysters?”

“Sit.”

“With a customer? A Paldan? I couldn’t possibly.”

“Sit down, I say.” I guessed an apology was forthcoming, but nothing in the Warden’s manner suggested contrition. I made a show of glancing around the room before sitting.

“Zedekapriam, I came here tonight because I was told you would commit a crime, nothing more. I have no vendetta against you personally. Do you understand why I have to say this?”

By his expression, I guessed he was more concerned with his reputation than my wounded feelings. Not exactly surprising. “Because my family is from Ape Head Bay,” I said, “and you have recently fought there.”

“Fought and lost. Your archers tore us apart.”

“You must have distinguished yourself in some manner to have earned this post.”

The Warden waved the remark away. In Pald, men simply did not compliment other men. “Tonight,” he said, “I have been played like a cadet in his first tenday at school. Worse, I must say something which places my reputation in your hands.”

I bowed my head. “You have my complete discretion.”

The Warden frowned, but he had come this far, and would not turn back. “I gave Jugun a small sum to purchase kepple, which he claims to have given to you. I wonder… Sir, why do you smile?”

His voice was sharp with wounded pride; I ignored it. “Good sir, the only thing more preposterous than the suggestion that I sell kepple is that the mayor’s nephew would ever give me money.”

“The man doesn’t pay you?” the Warden said, as though catching me in a bald lie.

“His uncle’s steward settles his bill every third tenday.” The Warden scowled and stood. “May I ask what you intend, Warden?” I could not have the man searching the house for Jugun, but I certainly could not seem anxious about it, either.

He paused. “Confront the man, of course.”

“Now? While he is drunk and probably empty of pocket?” I gestured toward the chair the Warden had just vacated, and he settled back into it. “Tomorrow, in the mayor’s home, he will be hung over and ill-inclined to argue. If he refuses to return the money, you need only raise your voice slightly. Jugun is terrified that his uncle will take notice of some misdeed and throw him out. You will likely find satisfaction then.”

The Warden drummed his fingers on the table. “You are telling me to choose a battlefield to my own advantage. Well, what do I owe you for this advice?”

Our new Warden had spent enough time in Ape Head Bay to know nothing from a Jallaran was free. “One thing, good sir. Do not tell Jugun we have had this chat.” I began fussing with my hair, a gesture a Paldan soldier would find alarmingly feminine. “For some reason, he has taken a distinct dislike to me.”

The Warden stood, his face blank and his lips tight. “You have my word,” he mumbled, and fled from the building.

Aneek rushed out of the kitchen. “What happened?”

The lead cook leaned against the bar. No more meals to cook tonight. “Would you turn out the front light, please?” I asked him. “We’re closing.” I turned toward Aneek. “He apologized, although he didn’t offer to cover tonight’s losses.

“My dear, the Sable Room is empty, I believe. Go up there and get me a pair of manacles. I’ll also need a sewing kit and two tweezers, please. Hurry, now. I’ll be downstairs.”

I took a pair of tongs from the stove. Fishing the keys from my belt, I unlocked the basement and padded down the steps. The staff believed I hid treasures down here: pearls, jewels and golden statues of my heathen Jallaran gods. The truth would have disappointed them. There was only a sewing bench, a wardrobe full of last year’s fashions, four oil lamps, and at the moment, a corpse. Maybe they would not have been disappointed after all.

With the tongs, I tossed the stitch bag onto the bench, then I kicked the bloody bed sheets into the corner. Jugun lay on his back as if sleeping. He seemed smaller, as though my puncture had released something, leaving only an empty bag. A shame I hadn’t known about the stitch magic before I killed him. He was only a pawn. If I could have relieved him of the bag, I could have preserved his life. And his continued patronage.

Money long spent, now. No use getting misty over it.

Aneek knocked and I let her in. Without a glance at the corpse, she closed the bottoms of the laundry chutes, then opened the wardrobe. Shoving the old clothes aside, she opened the panel in the back and removed eight cast iron levers.

“Slow down, my dear. I have barely begun.” I removed Jugun’s purse. It contained 18 gold apes and 21 copper monkeys. I found five more apes in his boots. They always hid some in their boots. There was nothing else but personal jewelry and a belt knife with silver inlay. Valuable, but too easily recognized.

“It’s time, then.” With the levers, Aneek and I lifted one of the floor stones, exposing a pit into the sewer below.

“Feh,” Aneek covered her nose. “I hate this part.”

“Let’s hope you shut the laundry chutes securely, or we will lose even more customers tonight.” I shoved the body into the pit, along with his jewelry, knife and silk clothes. In another tenday the Public Men would divert the river to sluice the sewers clean. By then, nothing would be left of the mayor’s nephew but a handful of trinkets and rat-gnawed bones. We laid the stone back over the pit and hid the levers in the wardrobe.

Aneek turned the oil lamps to their highest flame to burn out the stench. “Now I need a bath.”

“Not yet, my dear.” I took the manacles from her belt and chained her to the work bench. “We have a bit more to do.”

With the tongs, I turned the bag on its side. It was smaller than a folded handkerchief and consisted of two simple squares of cloth stitched together. I took out my sewing kit, located the knot binding the two halves and snipped it off. Using tweezers, I pulled the thread until the bag was open on one side.

It was full of green glass beads and boiled spices. I might have found it fragrant, if the room had not reeked like a sewer. I tweezed out several beads, then a tiny black pearl. I set it on the desk. Someone had spent a goodly amount of gold to hex me.

Using the tweezers to hold the needle, I restitched the bag and knotted it shut. It was a delicate business, closing the bag without letting it touch me, but my hands are steady and I like that sort of work. I turned to Aneek when I was done.

“Pick it up.”

She reached out with her free hand and lifted the bag. “Nothing,” she said. “The hex is gone.”

“Excellent!” I unlocked the manacles. “Take it into the bath with you, please. Wash out the smell but do not damage it. I have plans for it.”

Although I grew anxious with waiting, the Warden did not return until the next supper time. I’d already told Banu I’d send her back upriver with enough coin to care for her mother. Several of the staff offered her small gifts that afternoon; Aneek gave her a quilted Tilpic vest that would be the cutting edge of fashion in the provinces. Her barge sailed in the morning.

Once again, the main room was nearly empty all day. Without street theater, the Foreign Quarter was a dreary place. Without revenues from the performers, the Foreign Merchants Association would turn to street theivery for their money. My best customers were actually spending time with their wives and children.

When he finally arrived, the Warden was accompanied by Lodol and six Public Men. “We have some questions for you,” he said, in a tone that made my few customers toss coins on the tables and leave. All except the magistrate with the gaudy sash, bless him.

“Of course, gentlemen. Always a pleasure to serve. Shall we step into a private…”

“What have you done with Jugun Kickolan?” Lodol said.

“Why, nothing, First Man Lodol.”

“Is he still here?” the Warden asked.

“He has not returned, sir. He does not visit every day.”

“Returned?” Lodol said, raising his voice and shaking a gloved fist at me. “Then he left here? When?”

I tried to back away. “Last night, sir. Late, sir.”

“Who saw him go?”

“Only me, sir, and — ”

Lodol leaped on my hesitation like a hungry dog on a bone. “Who? The whore he was with? I want to speak to her immediately.”

Banu was summoned. I led them upstairs to the Mahogany Room, all the while glancing toward the exits. Lodol noticed, of course, and ordered his Men not to let me leave. He dragged Banu into the room.

“Warden!” I called. Lodol closed the door, and the Warden remained in the hall. Once again he stared at me as if I was a stain. “Really, Warden, after our conversation last night, I’d have thought all this unnecessary.”

“We’ve made inquiries,” he said. “No one saw him leave. He didn’t go home for money or clean clothes.” He looked toward the door of the Mahogany Room. We heard Lodol begin shouting, and Banu break into sobs. “If you have something to tell me, now is the time.”

I began to babble. Nothing incriminating, but I danced around a confession. I insisted I did nothing to the man, although I certainly had the chance, and I certainly had been insulted and almost sent to the cages. The Warden said nothing. He stared at me, waiting for some misstep.

Lodol burst into the hall. “Where is she? Where is his damned helper?”

They emptied the building, but Aneek was not found. The Warden wasn’t concerned. He slapped manacles on me. They were identical to the pair we used in the Sable Room.

The Men dragged me to the porch and down the stairs. Lodol padlocked the front door, and the Warden hammered a notice to the post. Closed By Order Of The Public Men.

They threw me into a rolling cage. Banu sat beside the Warden and began a steady stream of tearful whimpering.

We rode through the Wall into the respectable part of Pald, where no foreigner was allowed to reside, or even travel without written permission. A dismal place, despite its wealth. The houses squatted in the fading daylight. The clack of hooves echoed along empty brick streets. During the hour-long trip to the city cages, I heard no children playing, saw no wives gossiping. It was empty of life and joy.

At the court, Lodol shoved me into an empty cage, then left to further interrogate Banu. I looked around. The cell was cleaner than my booth in Sansunus’ kepple house.

After an hour, they returned. The Warden sneered. “Did you think you could play me, you Jallaran pig!” He struck me twice across the face, until Lodol explained that body blows would be less visible in court.

The beating resumed. I tried to protect myself, but I am only a fat whoremaster, while the Warden was a seasoned campaigner. It lasted a surprisingly long time; the man was even more protective of his reputation than I’d suspected. It only ended when Lodol suggested they save something for the hangman.

They left, and I lay on the cot, hoping nothing was broken. It is exceedingly difficult to bow and scrape with cracked ribs. I had nothing to do but listen for the sound of rats.

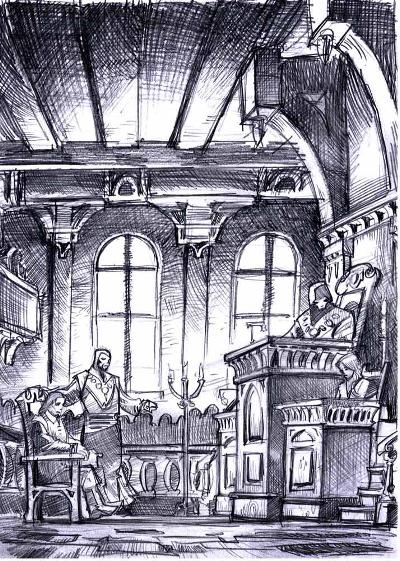

In the morning, three Public Men dragged me from my cell. We marched into court and they chained me to the iron chair. I had been moved to the front of the docket.

In the morning, three Public Men dragged me from my cell. We marched into court and they chained me to the iron chair. I had been moved to the front of the docket.

Banu stood beside the Warden at the witness stand. Lodol sat beside the mayor in the Honored Spectator section. I twisted in my chair and looked behind me. The citizen stands and both balconies were packed with men and women jostling for a seat and murmuring about the case. I saw respectable women of Pald, who rarely visited the Foreign Quarter.

And all of them were as fat as ten-copper chickens. According to Paldan folklore, plump women were best for hearth and children, while a skinny girl was possessed of ravening, unquenchable passions. A slender woman was held to be a ruinous wife, who would grind down her husband’s strength at night, and wander the streets for more during the day.

All very silly, of course, but young girls stuffed themselves with pastries to attain marriageable weight. Those who failed were called man stealers and whores right in the street, based solely on the girth of their upper arm. They were scorned.

Unless they worked for me. Paldan men paid well for small doses of passion, and there’s nothing like a bit of land, a chest of gold apes and a few padded dresses to insure a girl’s good marriage and a place in society. Somewhere far away, of course.

I couldn’t help but smile; this city seemed built to make me a rich man, if only I could solve my little problem.

Several plump matrons noticed that smile, and began to whisper and sneer at me. I searched the crowd for a friendly face. Sansunus sat in the front of the foreign citizen section.

Then I noticed Captain Onsooloc. He raised both fists to me, in a gesture meant to offer courage. I was quite touched.

After the crowd settled, the Honorable Magistrate entered. It was my magistrate, of course, with the gaudy sashes. My best customer. It was his day at the bench.

Everyone but me stood until the Honorable Magistrate took his seat. One of the Public Men gagged me to insure my silence before my Paldan superiors. The Warden announced the charges while the Magistrate read along from a paper at his bench.

The Honorable Magistrate pursed his lips. “Got yourself in a terrible mess, hey?” I could only shrug. “Who’s the witness?”

“A Paldan farm girl named Banu.” The Magistrate waved his hand, and the Warden proceeded with the questioning.

For his first time before the bench, the man did exceedingly well. His tone was stern but impartial, and he questioned her in a manner designed to build suspense in the citizen section. Banu admitted she knew Jugun Kickolan was missing, and that she had heard he could be found near the docks. He had been taken there, or rather his dead body had, in my carriage.

“Do you know how he died?” the Warden asked.

“He was killed,” she said, with so much regret it nearly broke my heart. “Zed stabbed him.”

“He was killed,” she said, with so much regret it nearly broke my heart. “Zed stabbed him.”

The court erupted into a furious clamor. Banu shouted that I was protecting her honor, but those who heard her above the tumult only jeered. She was, after all, a whore in a whorehouse.

The Honorable Magistrate struck his bell. It made a tiny ding, but the Paldan citizens heeded it like lap dogs. The room fell into silence. “Girl, have you told us the truth?” Miserable, Banu looked up at the magistrate and nodded.

“Look in her pocket!” a woman shouted from the upper balcony. All heads turned toward her. “She lies! And the proof is in the pocket of her vest!” It was Aneek, right on cue.

There was more outraged clamor. One does not shout at a magistrate from the upper balcony, after all. Lodol leaped from his seat and ordered her apprehended, declaring her the second killer. But Aneek was walking toward the Public Men, rather than fleeing them. She was dragged down the stairs and brought before the Magistrate. “What proof is this, An– er, woman?”

“I saw First Man Lodol question her. He slipped something into her pocket and she changed her story.”

“A bribe, hey?”

In another breach of protocol, Lodol jumped to his feet. “She can’t make such a claim! I was alone with the girl!”

The Honorable Magistrate seemed inclined to ignore protocol for the moment. He looked to Aneek for her response, and she said only: “It was in the Mahogany Room.”

A spark of recognition lit his face. He had frequented that room several times. “And is there a hidden place in this Mahogany Room, where one might observe the inhabitants without their knowledge? Voyeuristically, so to speak?”

“There is.”

“Give me the vest.”

Banu gave him the quilted vest, explaining that it had no pockets. But of course, it did: a hidden inner pocket the Tilpics called the merchants’ purse.

“Be careful,” Aneek said. With a wary glance at her, the Magistrate turned the garment upside down and shook it. Something plopped onto his desk.

He leaped from his chair, inciting a gasp from the courtroom. Every eye strained for a better view.

“What is it?” the Warden asked, reaching out his hand. The Magistrate caught his wrist. The Warden had fought Jallarans at Ape Head Bay, but the Honorable Magistrate was of an earlier generation and had campaigned against a different foe.

He drew his knife. “I haven’t seen one of these in years, but I haven’t forgotten. A Lisk stitch bag. See these letters? Anyone holding the bag is consumed with hatred for a single man: in this case, the accused. Dozens of officers were killed by their most loyal men because of these wretched things.” He slit the bag open, dug the point of his knife inside and flung beads and boiled twigs onto the courtroom floor. “Cut his gag.”

Two Public Men walked toward me, and Lodol leaped from his seat again. “Magistrate! I know nothing of…”

“Speak out of turn again,” the old juror said, “and I’ll have you whipped.” He suddenly pointed at the stands. “Seize that man!” I turned. Sansunus was halfway to the aisle. Two Public Men caught him by the arms and dragged him toward the cages. The Lisk opened his mouth, but failed to think of anything to say. By the time I resettled in my seat, the mayor was no longer sitting beside the First Man.

“What of it, hey? Have you proof to deny these charges?”

My gag was removed. “I thank you, Honorable sir, for the chance to speak in my defense. For proof, I can say only that, at the present time I have no carriage. It is being held in a wheelwright’s shop across the river due to a dispute over the cost of a repair, lasting some five or six days.”

“A statement which is easily confirmed,” the Magistrate said. “Warden, release the witness. Nothing in her testimony can be trusted. Release the accused as well, and escort First Man Lodol to the cages. I shall investigate this matter personally. Bring this woman,” he pointed to Aneek, “to my chambers. I shall hear the full details in private.”

Two Public Men began unlocking my chains. Pearls in the sky, that iron chair was uncomfortable. Aneek was escorted to the magistrate’s private chambers, and the Warden slapped manacles on Banu’s wrists. No doubt he intended to charge her with oath-breaking. It took five Men to manacle Lodol and drag him off. The respectable Paldans in the citizen section were shocked by the language he used.

Two Public Men began unlocking my chains. Pearls in the sky, that iron chair was uncomfortable. Aneek was escorted to the magistrate’s private chambers, and the Warden slapped manacles on Banu’s wrists. No doubt he intended to charge her with oath-breaking. It took five Men to manacle Lodol and drag him off. The respectable Paldans in the citizen section were shocked by the language he used.

Freed, I tried to stand, but the Warden shoved me back into the chair, then motioned his Men to step away. “You have played me, sir!” he said, in a harsh whisper. Here, finally, was my chance to solve my problem. My real problem.

“My dear Warden,” I answered, in an equally subdued tone, “everyone has played you. Jugun took your coins, Lodol shielded Pald’s largest kepple merchant, and Sansunus tried to parlay your rigid ideas about law enforcement into a noose around my neck.”

“I am sworn to enforce the law,” he said. “Every law.”

I touched the bruises on my jaw. “Even laws against the beating of prisoners? Oh, don’t make such a face. I am helping you. Even now Aneek is telling the Magistrate that you had certain suspicions about the behavior of your First Man, and that she spied on his interrogation at your direction.”

“And you expect him to believe her?”

“Before becoming my assistant, Aneek worked in the rooms of my house. The Honorable Magistrate has a fondness for stern women and they have a relationship going back many years. Besides, she will only hint, the Magistrate will deduce the rest. The Lisk has been trying to buy me out for months. Having failed, he turned to the kepple addicts among his customers. Anyone who saw Jugun’s stained fingers knows he is one of these, and what do you think the Magistrate will discover when he orders Lodol to remove those ridiculous gloves?”

The Warden actually looked surprised. “Stained fingers?”

“If I had swung from the gibbet, the mayor would have auctioned my property. With Lodol and Jugun’s help, Sansunus would have made the winning bid. Now, of course, it is their property which will be sold.”

“Then Jugun is alive?”

“In hiding perhaps, afraid to reappear. Unless Lodol cut his throat and planted the body somewhere. But he probably lives. Don’t worry, Warden. The Magistrate will keep this affair quiet, especially your heroic role, if only to protect the morale and loyalty of the Public Men serving under you.”

The Warden rubbed his face with both hands, then glanced around the room. The seats were still emptying, the people still buzzing over the morning’s dramatic testimony. “Is any of this true?” he asked, his voice aggrieved.

“My dear Warden, what odd questions you ask! Ask instead what will happen to Sansunus’ kepple house once it is auctioned. I suspect the Lisk’s suppliers will approach the new owner, and if that new owner is a friend of yours, you may make an even more noteworthy arrest. Another heroic ribbon on your sleeve.”

“A smuggler! I could cleanse the Foreign Quarter of kepple!”

“For two or three days.”

The Warden squinted at me. “You want the Lisk’s house?”

“That rat hole? Of course not, sir. After my favor to you, I will sell it again.” I didn’t need to add at a great profit.

The Warden nodded and stepped back, giving me room to stand. “What will these favors cost me?”

“First, send Banu back to the house. The poor girl is too delicate for these intrigues and hexes. I intend to send her home. Second, since we have established that certain laws need not be enforced, I’d like to discuss the ban against public performance. The Foreign Quarter thrives on an atmosphere of gaiety and revelry, and so do our businesses…”

“… I’ll consider it.” Judging by the tone of his voice, I knew he would do more than that.

“And last, smile. You have survived your first tenday as Warden, which is more than can be said for poor Lodol.”

Banu and I rode home together, accompanied by two Public Men. The full complement of my staff sat on the front steps of my house, waiting to either resume work or collect their things. The Public Men cut the padlock and left without a word.

The cooks and maids set to work preparing the house for the night’s business. The girls filed into the waiting room with Banu and me. They watched cautiously, still doubtful about me and my decision to force her to work a room against her will. Banu herself was terrified, perhaps afraid I would have her whipped.

Instead I presented her with a purse filled with Jugun’s apes and monkeys. I told her to put aside whatever false and ugly memories that hex bag had slipped into her mind. Then, for the medicine her mother needed, I gave her the tiny black pearl. After lunch, I escorted her to an upriver barge. She wept again and waved as she sailed away.

Aneek was livid when she found out, but she still didn’t understand. Banu did not matter, but the rest of the staff did. My generosity restored their confidence in me. They hugged me, pinched my plump cheeks and tousled my hair. When the sun set, and the musicians and mummers reappeared, the girls were in a high mood, the customers were delighted, and business was brisk.

I was standing on my front porch again, watching the people dance in the streets and laugh at the puppetry, when Bilby and two of his enforcers climbed the stairs.

“Welcome, Bilby! So wonderful to see…”

“Enough,” Bilby was short, but thick as a tree stump. He had killed at least a dozen men, and was probably the most dangerous man in the Foreign Quarter, if not the whole city. “Zedekapriam, due to the recent ban on street performance, the Foreign Merchants Association will be collecting a supplemental payment of half our normal fee, due by next sunset, to make up for our shortfall. Normal payment is still due at the end of the month.”

“Supplemental payment? Bilby, it is because of my efforts that the street players have returned!”

“I know, Jallaran. That’s why the payment is only half.”

I bowed. “Of course, sir. I understand your position entirely. Aneek will bring the money tomorrow.”

Bilby walked away, into the dance hall across the street. Supplemental payment, indeed! The expense of protecting myself from the Foreign Merchants Association was become onerous.

Something had to be done about it.

12 thoughts on “Special Fiction Feature: “The Whoremaster of Pald””