Blogging Sax Rohmer’s The Mask of Fu Manchu – Part One

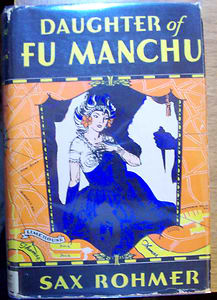

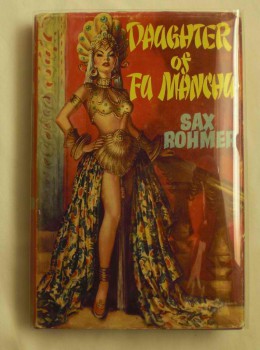

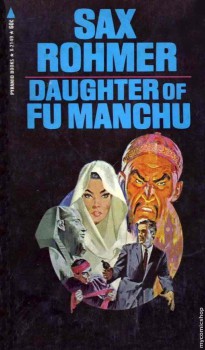

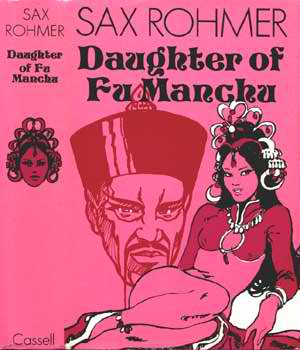

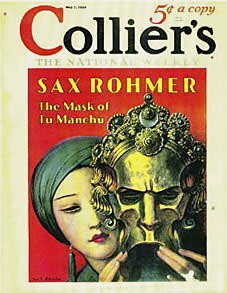

Sax Rohmer’s The Mask of Fu Manchu was originally serialized in Collier’s from May 7 to July 23, 1932. It was published in book form later that year by Doubleday in the US and the following year by Cassell in the UK. It became the most successful book in the series, thanks to MGM’s cult classic film version, starring Boris Karloff and Myrna Loy, that made it into theaters later that same year. Paramount’s option on the character had been exhausted after three pictures and one short starring Warner Oland as the Devil Doctor. The Paramount series had been responsible for Rohmer’s decision to revive the character with Daughter of Fu Manchu. The Mask of Fu Manchu served as a direct sequel and was again narrated by Shan Greville.

Sax Rohmer’s The Mask of Fu Manchu was originally serialized in Collier’s from May 7 to July 23, 1932. It was published in book form later that year by Doubleday in the US and the following year by Cassell in the UK. It became the most successful book in the series, thanks to MGM’s cult classic film version, starring Boris Karloff and Myrna Loy, that made it into theaters later that same year. Paramount’s option on the character had been exhausted after three pictures and one short starring Warner Oland as the Devil Doctor. The Paramount series had been responsible for Rohmer’s decision to revive the character with Daughter of Fu Manchu. The Mask of Fu Manchu served as a direct sequel and was again narrated by Shan Greville.

The novel gets underway with the brash Sir Lionel Barton having recently joined a colleague, Dr. Van Berg, in completing an excavation of the tomb of the notorious heretical Masked Prophet of Islam, El Mokanna, in Persia. Shan Greville, Sir Lionel’s foreman, is awakened in the middle of the night by his fiancée Rima Barton, Sir Lionel’s niece, who was disturbed by a strange wailing. Upon investigating, Dr. Van Berg is found dead in his room, his corpse slung over the jade chest containing the artifacts from the dig. The artifacts, still intact, are El Mokanna’s gold mask that hid his disfigured features, his heretical New Creed of Islam carved on gold tablets, and the bejeweled Sword of God with which the messianic prophet planned to conquer the world.