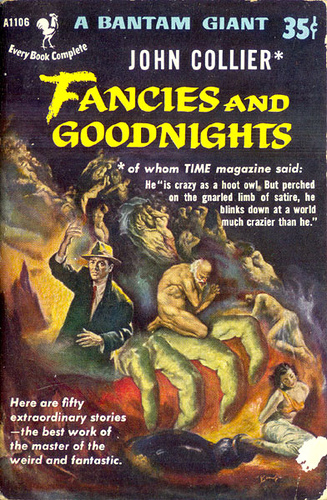

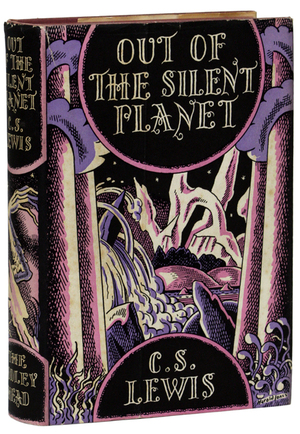

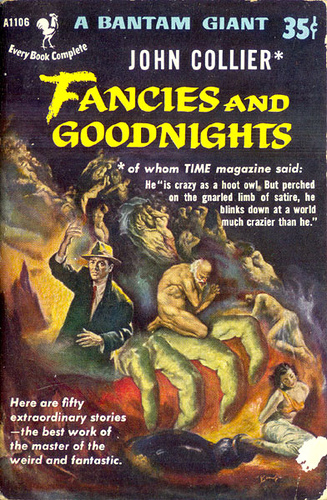

Fancies and Goodnights (Bantam Giant, 1953). Cover by Charles Binger

Fantasy, this genre that we love so much, is in reality not one genre but many; that’s one reason we love it. Any form that can accommodate the cynicism of Glen Cook and the lyricism of Patricia McKillip, that can hold the clarity of Robert E. Howard and the ambiguity of John Crowley, that can contain the brutality of George R.R. Martin and the hilarity of Terry Pratchett… well, there’s nothing it can’t do. Fantasy contains multitudes.

There’s a problem with being a member of a multitude, however — it’s easy to get lost, easy to be pushed to the back of the line by the ever-swelling mob of new books, new writers, new modes, easy to be misplaced or forgotten. It’s happened to many worthwhile writers. It’s happened to John Collier.

John Henry Noyes Collier, who died in 1980 at the age of seventy-eight, specialized in “slick” fantasy stories, “slick” because they generally appeared in “slick-paper magazines” as opposed to the cheap-paper pulps, upscale publications like The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, or Esquire. Characterized by modern, urban settings, a sophisticated, often satirical tone, and the irony-laced employment of traditional figures such as witches, genies, angels, devils, magicians, and ghosts, slick fantasy flourished during the twenties, thirties, and forties, and manifested itself in many different media. The humorous supernatural novels of Thorne Smith such as Topper (1926) and The Night Life of the Gods (1931), plays like Noel Coward’s breezy mix of marriage farce and spiritualism, Blithe Spirit (1941), and films like René Clair’s screwball comedy, I Married a Witch (1942, and itself the progenitor of one of the most popular television series of the 60’s, Bewitched), are all examples of this effervescent mode. John Collier may have been its greatest prose practitioner. …

Read More Read More