I had the sense of recognition…here was something which I had known all my life, only I didn’t know it…

English composer, Ralph Vaughan Williams on discovering English folklore and folk music

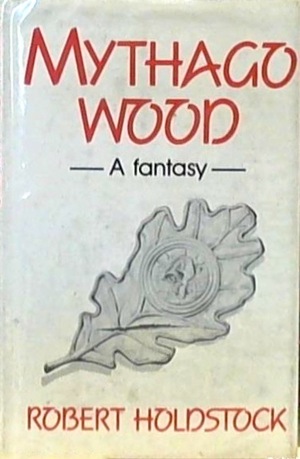

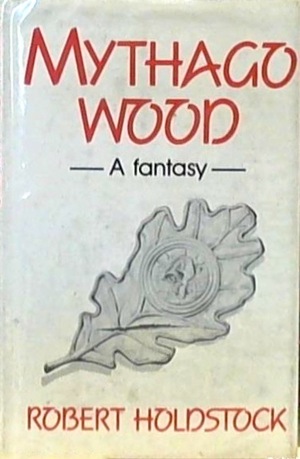

The late Robert Holdstock prefaced his 1984 novel, Mythago Wood with that quote, and that’s sort of how I feel about the book myself. Holdstock dug deeply into the idea of myth, how it might arise from a culture, and how, in turn, it might affect individuals.

I have no memory of when I first learned of Mythago Wood. I must have seen it on the Forbidden Planet’s shelves when it was released; I didn’t read it, though, until 2001. I read it again while traveling in England eight years later, and just now. At times it seems like I must have read it so much longer ago and more times than that. Much of it reads like a dream of some true past, equally joyful and nightmarish, and elements of it have rattled about my brain ever since. Rereading it now, I realize that over the years, my memories of the novel, like the mythic figures born of the forest around which the story revolves, have faded and changed with each passing season, but the underlying haunting design remains; a mesmerizing tale of father-and-son and brother-and-brother struggles, Freudian and Jungian elements, woven together with a wholly original mythopoeic retelling of the history of Britain from Paleolithic times to the present (or at least 1948, the present of the book). I will more than likely read it again before I’m through.

The central conceit of Mythago Wood is that archetypes and legends spring from the collective unconscious when needed.

The mythagos grow from the power of hate, and fear, and form in the natural woodlands from which they can either emerge — such as the Arthur, or Artorius form, the bearlike man with his charismatic leadership — or remain in the natural landscape, establishing a hidden focus of hope — the Robin Hood form….

Ryhope Wood, a three-mile square ancient woodland in Herefordshire, is capable of interacting with the minds of people near it and giving physical reality to these figures. Characters like Cernunnos, King Arthur, and Jack-in-the-Green can be summoned up from the deepest recesses of people’s minds. More importantly, it can also conjure up the legends that lie behind the legends. Perhaps the story of Robin Hood arose from even older stories of green-clad forest bandits, and behind those, yet older and darker ones. The more intimately a person becomes involved with Ryhope Wood the deeper and deeper ancient memories it can draw upon and summon forth. Ryhope Wood also exists beyond normal time and space, expanding, almost without limit, the further one ventures into it, and time speeds by much faster within the forest than without. Deep inside, whole settlements and tribes called out in long past days carry on telling and retelling their stories through their daily lives and routines.

…

Read More Read More