Deep in Wildest Britain: Mythago Wood by Robert Holdstock

I had the sense of recognition…here was something which I had known all my life, only I didn’t know it…

English composer, Ralph Vaughan Williams on discovering English folklore and folk music

The late Robert Holdstock prefaced his 1984 novel, Mythago Wood with that quote, and that’s sort of how I feel about the book myself. Holdstock dug deeply into the idea of myth, how it might arise from a culture, and how, in turn, it might affect individuals.

I have no memory of when I first learned of Mythago Wood. I must have seen it on the Forbidden Planet’s shelves when it was released; I didn’t read it, though, until 2001. I read it again while traveling in England eight years later, and just now. At times it seems like I must have read it so much longer ago and more times than that. Much of it reads like a dream of some true past, equally joyful and nightmarish, and elements of it have rattled about my brain ever since. Rereading it now, I realize that over the years, my memories of the novel, like the mythic figures born of the forest around which the story revolves, have faded and changed with each passing season, but the underlying haunting design remains; a mesmerizing tale of father-and-son and brother-and-brother struggles, Freudian and Jungian elements, woven together with a wholly original mythopoeic retelling of the history of Britain from Paleolithic times to the present (or at least 1948, the present of the book). I will more than likely read it again before I’m through.

The central conceit of Mythago Wood is that archetypes and legends spring from the collective unconscious when needed.

The mythagos grow from the power of hate, and fear, and form in the natural woodlands from which they can either emerge — such as the Arthur, or Artorius form, the bearlike man with his charismatic leadership — or remain in the natural landscape, establishing a hidden focus of hope — the Robin Hood form….

Ryhope Wood, a three-mile square ancient woodland in Herefordshire, is capable of interacting with the minds of people near it and giving physical reality to these figures. Characters like Cernunnos, King Arthur, and Jack-in-the-Green can be summoned up from the deepest recesses of people’s minds. More importantly, it can also conjure up the legends that lie behind the legends. Perhaps the story of Robin Hood arose from even older stories of green-clad forest bandits, and behind those, yet older and darker ones. The more intimately a person becomes involved with Ryhope Wood the deeper and deeper ancient memories it can draw upon and summon forth. Ryhope Wood also exists beyond normal time and space, expanding, almost without limit, the further one ventures into it, and time speeds by much faster within the forest than without. Deep inside, whole settlements and tribes called out in long past days carry on telling and retelling their stories through their daily lives and routines.

Narrated by Steven Huxley, a young Englishman wounded during the Second World War, Mythago Wood is told in a reserved, and cautious style that seems appropriate to the time and the character. It’s as if Steven wants to make sure the outlandish revelations and claims he makes will be better believed by his obvious skepticism. Speaking through Steven, Holdstock brings Ryhope Wood and its inhabitants fully, lushly to life. The smell of leaf mould and damp moss, sunlight refracted through the dense green leaf cover, and the calls of birds and other creatures rise out of the page almost tangibly.

Narrated by Steven Huxley, a young Englishman wounded during the Second World War, Mythago Wood is told in a reserved, and cautious style that seems appropriate to the time and the character. It’s as if Steven wants to make sure the outlandish revelations and claims he makes will be better believed by his obvious skepticism. Speaking through Steven, Holdstock brings Ryhope Wood and its inhabitants fully, lushly to life. The smell of leaf mould and damp moss, sunlight refracted through the dense green leaf cover, and the calls of birds and other creatures rise out of the page almost tangibly.

I walked for some minutes, against the flow of the water, the light dimming as the canopy grew denser. The stream widened, the banks became more severe. Abruptly it turned in its course, flowing from the deeper wood, and as I began to follow it so I became disorientated; a vast oak barred my way, and the ground dropped away in a steep, dangerous decline, which I circuited as best I could. Moss-slick grey rock thrust stubby fingers from the ground; gnarled young oak-trunks grew through and around those stone barriers. By the time I had found my way through, I had lost the stream, although its distant sound was haunting.

Steven Huxley and his older brother Christian grew up at Oak Lodge on the edge of Ryhope Wood. Their father, George, was obsessed with the forest, eventually to the exclusion of everything else. He alienated his wife to such a degree she sickened and died. He would venture into the small forest for days and even weeks at a time.

Steven is called up for army service in 1944, but before leaving Oak Lodge he steals a page from his father’s journal out of spite. Its contents prove puzzling and incoherent:

A letter from Watkins — agrees with me that at certain times of the year the aura around the woodland could reach as far as the house. Must think through the implications of this. He is keen to know the power of the oak vortex that I have measured. What to tell him? Certainly not of the first mythago. Have noticed too that the enrichment of the pre-mythago zone is more persistent, but concomitant with this, am distinctly losing my sense of time.

Convalescing and lolling about Southern France at the war’s end, he begins receiving letters from his brother back home at Oak Lodge. Over time it is clear there is growing tension between Christian and George and finally word arrives that George has died. Steven resolves to go home but puts it off for another year. When Christian sends him a letter telling him he lost his “heart, mind, soul, reason” to a girl named Guinwenneth and married her, then sends no letter for many months, Steven finally makes the journey.

When he arrives, Steven finds his brother weathered and worn and, perhaps most ominously, having the “distant, distracted look” of their father. Steven’s fear for his brother proves apt; Christian is pursuing their father’s research, whatever it might have been, and Guinwenneth is gone.

Eventually, Steven learns that Guinwenneth was killed by a Robin Hood-type figure, one, like her, born of the forest. Both were what George Huxley termed “mythagos,” myth-figures given life by the forest and drawn from the psychic energy of people nearby. Guinwenneth is part of an ancient story of a princess who brings natives and invaders together and was initially brought out of Ryhope by George. She fell in love, though, with Christian, which ultimately leads to George’s death. Christian tells Steven that he is entering the forest in hope of finding some new iteration of Guinwenneth, summoned by his own mind.

Even though past strange sightings seem to be explained by the mythago idea, Steven comes to believe in it only when figures start appearing in his peripheral vision after he begins exploring Ryhope Wood himself. Finally, he is visited one night by another Guinwenneth. Over time they fall in love and they live together in the Lodge. During their time together, Steven continues to explore the forest and encounters other mythagos as well, but never his brother.

One night, Christian returns changed, a violent man, accompanied by a band of killers. Though gone from the real world for only nine months, he has journeyed for fifteen years within the forest searching for his lost bride and hunted by the Urscumug, a dogged and monstrous boar-headed man representing a prototype defender against the first invaders. Christian rips Guinwenneth from Steven’s side, leaves his brother for dead, and returns to the wood.

Steven survives and realizes if he is to save Guinwenneth, he must plunge further into the forest than he ever dared or was able to go before. Accompanied by Harry Keeton, a pilot he hired to survey the wood from above, Steven finds himself involved in a quest that gradually weaves him into the fabric of Ryhope Wood.

The book is very much Steven Huxley’s story. Guinwenneth remains an elusive character on the page, more shaped by Steven’s dreams than her own spirit. What transpired to turn Christian into a killer happens off the page and is never revealed. I know Holdstock returned to these characters respectively in later books, Avilion (2009) and Gate of Ivory, Gate of Horn (1998). Still, here they are largely characters for Steven to react to. The only other perceptions of events the reader gets are from the pages of George Huxley’s and Harry Keeton’s diaries. Even these offer more mysteries than insights. It is in Steven’s voice, then, that the narrative is carried and in that, Holdstock achieved complete success.

Though it may seem I have told much, I have really described only a few pages of Mythago Wood. Much of the early part of the book reads like an old science-fantasy story as Steven uncovers the strange devices his father created and experiments he conducted in order to chart Ryhope Wood and call out mythagos. At other times it’s a detective novel, as Steven hunts for clues to what his father and several others had done in the past, as well as having to ferret out hidden items. Other chapters are taken up with the telling of mythic stories, sometimes clearly connected to the book’s narrative, other times less so. In the latter case, they seem to be there to underline that the present is so far removed from the past we can no longer find any obvious connection to it. Finally, it’s an epic quest that recounts a mythic history of Britain that gradually extends beyond any known elements of the past, where the mythagos he meets possess supernatural powers and reflect stories from the days after the last Ice Age ten thousand years ago.

I don’t know how much I accept the concept of archetypes as Jung believed, that they reflect some deep human ideal resonant across multiple cultures because of their shared, ancient history; for the sake of a story, though, I find it fascinating. The most prominent one, presented in the invented characters of Guinwenneth as well as the Urscumug, but also in King Arthur and Robin Hood, is that of the defender against the invader. In Mythago Wood, he or she is a figure tied intimately to the land and the people most connected to it. In British lore, just as Arthur’s legend arose to exemplify British defiance of the Saxons, five hundred years later Robin Hood was a Saxon story to wield against Norman domination.

Holdstock also explores how individuals are affected by myth and how they turn it to their own desires. The Urscumug hunts Christian because he is the ultimate invader, killing and despoiling his way through Ryhope Wood in search of Guinwenneth. It also hunts him because it arose from George Huxley’s mind and is imprinted with his enmity and jealousy toward his son. Later, as Steven quests after his brother, he finds himself succumbing to the story that the invader can only be stopped by a kinsman. He tries to bring the weight of that prophecy down on his brother, gradually turning far more driven and dangerous than he started out. At one point Keeton begins to ponder this very point.

For my part I find it continually fascinating to think that Steven has become a myth character himself! He is the mythago realm’s mythago. When he kills C the decay of the landscape will reverse. And since I am with him, I suppose I am part of the myth myself. Will there be stories told one day of the Kinsman and his companion, the stigmatized Kee, or Kitten, or however the names get changed?

I discern a kinship between older British writers Alan Garner and Henry Treece and the contemporary Paul Kingsnorth with Robert Holdstock. For them, the past isn’t a carnival of pastel gowns and flower rings tossed round the Maypole, or kindly druids and winsome witches. It is a dangerous place, sometimes dark, sometimes bright. Its customs are not ours; the past is very much a different country. The legends and heroic characters that still hold a place in Britain’s collective heart rose from a rough and wild place, where violence was common and steel and fire settled things more often than talk. Blood was paid with blood. In the face of that, legends grew that provided unity and the will to resist. There’s also a fierce connection to the land drawn, I suspect, from the obvious fear that it if is plundered and stolen away a people’s very essence, what makes them them will wither away.

I titled my review of Hope Mirlees’ Lud-in-the-Mist A Potent Draught of Distilled Fairy Fruit. Mythago Wood is a potent draught of something else entirely different: equal parts love, hate, and obsession, which smells of the ancient trees and sometimes reeks of the blood-soaked earth underfoot. From these elements, Robert Holdstock created stories that feel like real myths stretching backward in time from the Middle Ages, past the Saxon invasions, beyond even the arrival of the first Bronze Age invaders, to a time when the ice wall was only just beginning its retreat northward. This is a brilliant, captivating work that deservedly secured Holdstock’s reputation as an author of the first caliber.

All told, Holdstock wrote five novels and two short story collections related to Ryhope Wood and the idea of mythagos. Mythago Wood and Lavondyss (1988) both won the BSFA Award for best novel. In addition to many other novels under his own name, he wrote numerous potboilers, as well as sword & sorcery (some fair and some quite good) under pen names. I plan to pick up more of the series in the near future, finding myself nearly as ensnared by the lures of Mythago Wood as any of the men of the Huxley family.

Derek Kunsken wrote earlier about Mythago Wood and Lavondyss here.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

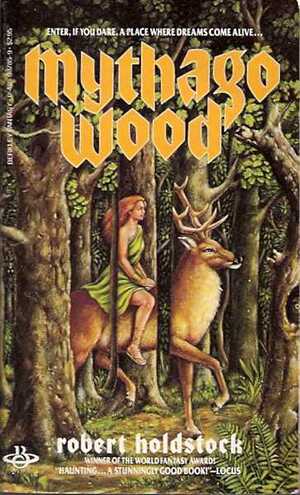

I remember being amazed by Mythago Wood and its follow-up Lavondyss. And then I went and lost all track of Mr. Holdstock’s writing, and time passed, and I occasionally flashed on the Rene Magritte homage cover of the Berkley edition. Oh well, perhaps the guilt will subside before I commit to hunting up every last part of the Mythago series. Perhaps.

I have been telling people for years to read MYTHAGO WOOD. It’s my favorite stand-alone novel. Holdstock’s narrative voice is perfect for the telling. I remember being stunned about halfway through my first read when I realized that among other things, the story was a romance. It managed to be a moving romance AND all the other things you describe. Also, it has the best ending of any book I’ve ever enjoyed. I remember gasping with pleasure when I finished the book. Even today when I go to the bookstore looking for something new, I’ll find myself holding a copy of MYTHAGO WOOD. I know that it will be a great read while those other books, I haven’t read yet, may prove to be a disappointment. Thanks for highlighting this truly marvelous story.

That’s one of the best recommendations I’ve read for a book ever

Mythago Wood blew my 14 year old mind open when I read it in the 80s. Apart from the setting, it had such fantastic ideas that completely absorbed your attention. If you’ve not read it, do it!