Fantasia 2018, Day 19, Part 2: Pourquoi l’étrange Monsieur Zolock s’intéressait-il tant à la bande dessinée? and Tokyo Vampire Hotel

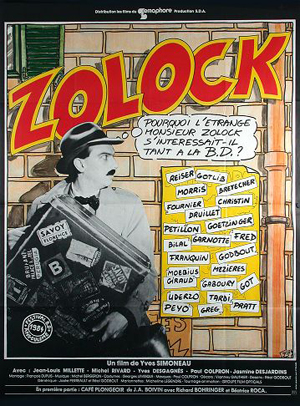

The Centre Cinéma Impérial is one of Montréal’s last surviving movie palaces. Built in 1913 as a vaudeville playhouse, it’s survived most of the past hundred years and change as a cinema. In 1996, the inaugural edition of the Fantasia International Film Festival was held at the Imperial, and Fantasia still returns there for a few screenings every year. It’s a beautiful location in which to view a movie. Currently boasting over 800 seats (including some up in a balcony), it has gilded scrollwork, putti, a proscenium arch around the screen. About twenty minutes’ walk east of the main Fantasia theatres in Concordia University’s downtown campus, it was my destination on the evening of Monday, June 30, for a screening of a 1983 documentary by veteran Québec director Yves Simoneau (perhaps best known to American genre fans for directing four of the first five episodes of the 2009 reboot of V). After that, I’d be hurrying back to the Hall Theatre for a crazed Japanese action-horror dark-comedy thrillride, Tokyo Vampire Hotel. First, though, I’d get to see the recently-restored 35-year-old documentary about European comics, Pourquoi l’étrange Monsieur Zolock s’intéressait-il tant à la bande dessinée?

The Centre Cinéma Impérial is one of Montréal’s last surviving movie palaces. Built in 1913 as a vaudeville playhouse, it’s survived most of the past hundred years and change as a cinema. In 1996, the inaugural edition of the Fantasia International Film Festival was held at the Imperial, and Fantasia still returns there for a few screenings every year. It’s a beautiful location in which to view a movie. Currently boasting over 800 seats (including some up in a balcony), it has gilded scrollwork, putti, a proscenium arch around the screen. About twenty minutes’ walk east of the main Fantasia theatres in Concordia University’s downtown campus, it was my destination on the evening of Monday, June 30, for a screening of a 1983 documentary by veteran Québec director Yves Simoneau (perhaps best known to American genre fans for directing four of the first five episodes of the 2009 reboot of V). After that, I’d be hurrying back to the Hall Theatre for a crazed Japanese action-horror dark-comedy thrillride, Tokyo Vampire Hotel. First, though, I’d get to see the recently-restored 35-year-old documentary about European comics, Pourquoi l’étrange Monsieur Zolock s’intéressait-il tant à la bande dessinée?

The screening was preceded by a presentation. Marc Lamothe, one of the Festival’s General Directors, recalled the early years of Fantasia at the Imperial Theatre. Marie-José Raymond spoke about the restoration; she’s one of the co-directors of Éléphant: mémoire de cinéma Québécois, a project dedicated to restoring and digitising Québec feature films. She was followed by businessman Pierre-Karl Péladeau, then by Simoneau and some of the local artists who participated in the film. Simoneau was presented with the Prix Denis-Héroux for his contribution to Québec cinema.

Pourquoi l’étrange Monsieur Zolock s’intéressait-il tant à la bande dessinée? won a Genie award (the Canadian film industry awards from 1980 to 2012, now the Canadian Screen Awards) for Best Feature Length Documentary. Written by Marie-Loup Simon, it follows a private investigator named Dieudonné (Michel Rivard) who’s hired by a mysterious man named Zolock (Jean-Louis Millette) to investigate the appeal of bandes dessinées — French comic books. Dieudonné himself seems to have stepped out of a comic, in his trenchcoat and fedora; Zolock too, a master criminal whose house is dominated by a black room where Zolock first meets Dieudonné, and, at the end, explains his interest in comics. In between, Dieudonné travels about and interviews the leading European and Francophone comics artists of the day.

The result is a murderer’s row of comics talent. Very nearly every major figure in European comics alive and working at the time makes at least a brief appearance here. Interviewees include, in no particular order, Jean Giraud (Mobius), Hugo Pratt, Claire Bretécher, Philippe Druillet, Albert Uderzo, Pierre Culliford (Peyo), Maurice De Bevere (Morris), Franquin, Jacques Tardi, Yves Got, Annie Goetzinger, and Enki Bilal — as well as Québec artists Garnotte, Serge Gaboury, Réal Godbout, and Pierre Fournier. The names alone make this film a major document in comics history.

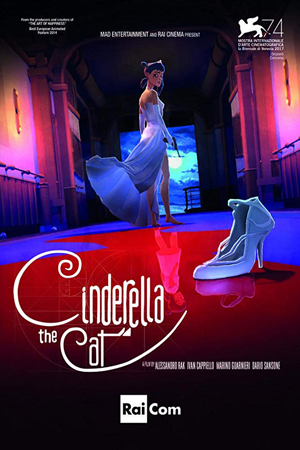

I had three films on my schedule for Monday, July 30. First, an animated science-fictional retelling of Cinderella for adults, called Cinderella the Cat. Then I’d hurry from the J.A. De Sève Theatre to the Centre Cinéma Impérial, where Fantasia was presenting a documentary from the early 80s about bandes dessinées: Pourquoi l’étrange Monsieur Zolock s’intéressait-il tant à la bande dessinée? Then I’d run back to the Hall Theatre for a presentation of Sion Sono’s Tokyo Vampire Hotel, a kinetic horror-action film with campy apocalyptic overtones. Even for Fantasia, it was going to be a strange day.

I had three films on my schedule for Monday, July 30. First, an animated science-fictional retelling of Cinderella for adults, called Cinderella the Cat. Then I’d hurry from the J.A. De Sève Theatre to the Centre Cinéma Impérial, where Fantasia was presenting a documentary from the early 80s about bandes dessinées: Pourquoi l’étrange Monsieur Zolock s’intéressait-il tant à la bande dessinée? Then I’d run back to the Hall Theatre for a presentation of Sion Sono’s Tokyo Vampire Hotel, a kinetic horror-action film with campy apocalyptic overtones. Even for Fantasia, it was going to be a strange day.

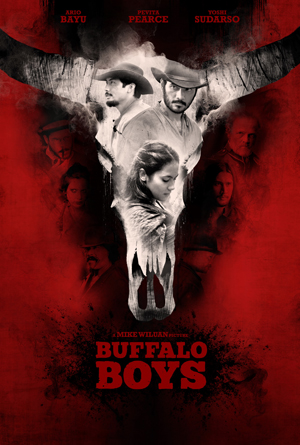

Before writing about the movies I saw during the last weekdays of the Fantasia festival, I’m going to skip back to the beginning to write about some films I watched before attending my first screening this year with a general audience. At a festival with 130 movies, most of which are shown in a theatre once or maybe twice, one has to make some hard choices about which to see. Fortunately, Fantasia’s screening room gives harried film critics the chance to catch some of the movies they have to miss in theatres due to one scheduling exigency or another. I passed by on the first day of the festival, and found that this year the screening room offered curtained cubicles and a healthy selection of films. Among them was an Indonesian western named Buffalo Boys, an experimental German horror film called Luz, and a transgressive French animated webseries titled Crisis Jung.

Before writing about the movies I saw during the last weekdays of the Fantasia festival, I’m going to skip back to the beginning to write about some films I watched before attending my first screening this year with a general audience. At a festival with 130 movies, most of which are shown in a theatre once or maybe twice, one has to make some hard choices about which to see. Fortunately, Fantasia’s screening room gives harried film critics the chance to catch some of the movies they have to miss in theatres due to one scheduling exigency or another. I passed by on the first day of the festival, and found that this year the screening room offered curtained cubicles and a healthy selection of films. Among them was an Indonesian western named Buffalo Boys, an experimental German horror film called Luz, and a transgressive French animated webseries titled Crisis Jung.  By Eva and Matthew Surridge

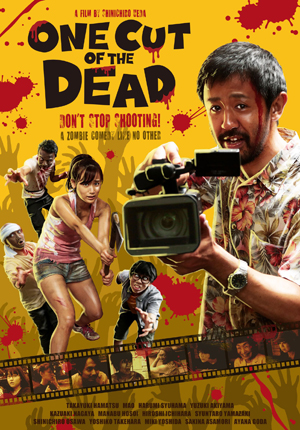

By Eva and Matthew Surridge I settled in at the Hall Theatre on the evening of Sunday, July 29, to watch a movie about which I knew little. I knew it was Japanese, I knew it was titled One Cut of the Dead (Kamera o tomeru na!, カメラを止めるな!), and I knew it was written and directed by Shinichiro Ueda. The movie ended up being excellent and even uplifting. But writing about it presents a challenge.

I settled in at the Hall Theatre on the evening of Sunday, July 29, to watch a movie about which I knew little. I knew it was Japanese, I knew it was titled One Cut of the Dead (Kamera o tomeru na!, カメラを止めるな!), and I knew it was written and directed by Shinichiro Ueda. The movie ended up being excellent and even uplifting. But writing about it presents a challenge. Sunday, July 29, was an intriguing day. Not so much because of the first movie I planned to see, an anime called Penguin Highway about a young boy investigating the mysterious appearance of penguins in his small Japanese town. But because of the second screening, the International Science-Fiction Short Film Showcase 2018. It’d present eight films, and having seen prior editions of the showcase, I knew how unpredictable it would be.

Sunday, July 29, was an intriguing day. Not so much because of the first movie I planned to see, an anime called Penguin Highway about a young boy investigating the mysterious appearance of penguins in his small Japanese town. But because of the second screening, the International Science-Fiction Short Film Showcase 2018. It’d present eight films, and having seen prior editions of the showcase, I knew how unpredictable it would be. The last movie I saw on Saturday, July 28, was at the Hall Theatre. It was Punk Samurai Slash Down (Panku Samurai Kirarete Soro, パンク侍、斬られて候), an adaptation of Ko Machida’s 2004 novel directed by Gakuryu Ishii and scripted by Kankuro Kodo (who also wrote

The last movie I saw on Saturday, July 28, was at the Hall Theatre. It was Punk Samurai Slash Down (Panku Samurai Kirarete Soro, パンク侍、斬られて候), an adaptation of Ko Machida’s 2004 novel directed by Gakuryu Ishii and scripted by Kankuro Kodo (who also wrote  Saturday, July 28, saw me arrive at the Hall Theatre early for a showing of the Japanese historical fantasy Laughing Under the Clouds, yet another manga adaptation. Following that, I’d head across the street to the J.A. De Sève Theatre, where I’d watch a short film showcase called Afromentum. It’d feature four short films by Black filmmakers from around the world — including an adaptation of Nnedi Okorafor’s short story “Hello, Moto.”

Saturday, July 28, saw me arrive at the Hall Theatre early for a showing of the Japanese historical fantasy Laughing Under the Clouds, yet another manga adaptation. Following that, I’d head across the street to the J.A. De Sève Theatre, where I’d watch a short film showcase called Afromentum. It’d feature four short films by Black filmmakers from around the world — including an adaptation of Nnedi Okorafor’s short story “Hello, Moto.”