Fantasia 2017, Supplemental: Satires and Wars (Japanese Girls Never Die, Broken Sword Hero, and God of War)

After the Fantasia festival had officially concluded I still had three movies to watch. During the festival I’d requested links to view screening copies of three films I couldn’t see in theatres due to schedule conflicts, but it wasn’t until Fantasia ended that I had time to sit down and watch them. These movies were a Japanese comedy-drama called Japanese Girls Never Die (also released under the English title Haruko Azumi Is Missing, in romanised Japanese Azumi Haruko wa yukue fumei); a Thai historical martial-arts movie called Broken Sword Hero (also Legend of the Broken Sword Hero, from the romanised original Thong Dee Fun Khao); and a Chinese blockbuster historical war movie called God of War (Dang kou feng yun, now on Netflix). They made for an interesting mix.

After the Fantasia festival had officially concluded I still had three movies to watch. During the festival I’d requested links to view screening copies of three films I couldn’t see in theatres due to schedule conflicts, but it wasn’t until Fantasia ended that I had time to sit down and watch them. These movies were a Japanese comedy-drama called Japanese Girls Never Die (also released under the English title Haruko Azumi Is Missing, in romanised Japanese Azumi Haruko wa yukue fumei); a Thai historical martial-arts movie called Broken Sword Hero (also Legend of the Broken Sword Hero, from the romanised original Thong Dee Fun Khao); and a Chinese blockbuster historical war movie called God of War (Dang kou feng yun, now on Netflix). They made for an interesting mix.

Japanese Girls Never Die was directed by Daigo Matsui (whose earlier film Wonderful World End I quite liked), from a script by Misaki Setoyama based on the 2013 novel by Mariko Yamauchi. I can find out nothing about the novel, but the film is wondrously, deliriously complex, bristling with different timelines, subplots, and minor characters who send the film spinning off in different directions. It’s quick, challenging, and engaging.

There is Haruko Azumi (Yu Aoi, of the Rurouni Kenshin movies), an office worker in her 20s who has an unrequited love for her neighbour. There are two young grafitti artists (Shono Hayama and Taiga), at a later point in time, who find a poster of the missing Haruko and make street art from it. There is a gang of teen girls who terrorise the same streets, so that men are advised not to walk those streets at night. There is an older woman at the office where Haruko works, mocked by the men there for not having children and not being young and not being their fantasy image of a woman. There is a girl who is involved with one of the graffiti artists, who in turn are using her more than she realises. There is a clerk at a convenience store. There is a park called Dreamland. There are characters who may or may not attain their dreams. There is an unexpected beginning.

It’s a complex film, if easier to watch than this summation might suggest. The movie tends to break down into two main timelines, one following Haruko and one the graffiti artists, which helps to give the timeframes a distinctive focus; by the end, of course, they dovetail one into another. The girl gang makes a kind of connective tissue, while opening and closing scenes with the gang at a movie theatre suggest a metafictional touch (as if there wasn’t enough going on in the film).

It’s a complex film, if easier to watch than this summation might suggest. The movie tends to break down into two main timelines, one following Haruko and one the graffiti artists, which helps to give the timeframes a distinctive focus; by the end, of course, they dovetail one into another. The girl gang makes a kind of connective tissue, while opening and closing scenes with the gang at a movie theatre suggest a metafictional touch (as if there wasn’t enough going on in the film).

There’s a reflexive bleakness in the movie that emerges from trying to look deeply at the situation of women in Japan (and, one might well argue, in the rest of the world as well). There are escapes imagined, and if they’re unlikely they still seem to have significance. But this is an angry film, one driven by a satirical anger that is itself based in a realist vision. As in much of the best satire, the very openness to reality seems to insist on a fractured, fantastical view: the reality is, in essence, nonsense, so how to describe that without this kind of kaleidoscopic, heightened world? A vocabulary of symbols builds up in the movie, and a kind of vocabulary of relationships as well. We see patriarchal norms not just in the society the film depicts, but in the way the characters relate.

It’s not encyclopedic. There’s not much discussion of queer themes, for example, which would seem relevant in a film otherwise interested in sexual politics. It’s a character-based social satire, then, that keeps its focus across two different but related plots and throws in a certain amount of surrealism and symbolism to sharpen its points.

It definitely works, but I did find it a challenge to watch. It moves quickly, and its transitions between timeframes aren’t always obvious. The film builds up two sets of characters, two different social webs, and for some reason I found it difficult to keep those two networks separate in my head as I watched; things moved so quickly my memory began to blur at the edges. It is entirely possible that this was simply a kind of hangover from watching too many movies in too short a span of time, but given how much else is going on in this film, I have to say it felt deliberate, a tactic to dislocate the audience even further.

That said, the estrangement only goes so far. There’s always something engaging going on moment by moment, whether violent action with the girl gang, or a solid character scene like Haruko having a heart-to-heart talk with her older worker. As the film goes on one figures out how to watch it, how to order it in one’s head. The puzzle pieces start to assemble themselves.

That said, the estrangement only goes so far. There’s always something engaging going on moment by moment, whether violent action with the girl gang, or a solid character scene like Haruko having a heart-to-heart talk with her older worker. As the film goes on one figures out how to watch it, how to order it in one’s head. The puzzle pieces start to assemble themselves.

Is there a point to the scrambled structure? I can think of a few things it does. It could be said, for example, to represent a scrambled consciousness; perhaps what happens to Haruko as she tries to fit herself into a socially-accepted role. I note that the movie deals with women and girls across a wide age range, so the different timeframes might also reflect the diversity of women’s experience at different ages. And, of course, on a practical level, the fractured structure opens up a certain approach to plot, symbolism, and heightened reality: it creates a specific feel.

In watching a film from another culture, one never really knows what one’s missing; that’s even more true in the case of a highly socially-engaged satire. I can’t know how much I don’t know. I can say that this movie seems to me to make sense. I can say that the acting seems uniformly strong, if often subdued, and Aoi in particular crafts a character who has a feel of solid reality among an often extravagant world. I can certainly say I enjoyed and appreciated the movie. I have no idea how it plays in a Japanese context. But it seems to me that the repression of women is enough of a global problem that the basic theme is comprehensible across cultures, whether the specific manifestations are familiar or not. On the other hand, not being a woman I’m again speaking about this subject from the outside. Again, I can only say what my personal perceptions are; and if that’s the task of the critic in any case, it’s also true that not every statement or analysis will be equally valuable. So for what it’s worth my reaction to the film was positive: it struck me as a clever, structurally complex, character-based work. Beyond that, I can only defer to more knowledgeable analyses.

It’s a little simpler as a critic, I find, to write about genre films; theoretically, those kinds of stories have a core of elements that work in similar ways across cultures. That’s far from inevitable — horror, for example, may emerge from wildly different cultural aspects, as does humour — but I’d say it’s broadly true that action movies in particular work well across linguistic and cultural divides. You by and large know what you’re looking for in an action film, and can judge it accordingly. Which brings me to Broken Sword Hero, directed by Bin Bunluerit from a script by Buakaw Banchamek and Phutharit Prombandal. Banchamek also stars as hero Joi (AKA Thongdee); the character’s loosely based on a real 18th-century warrior, Phraya Pichai Dap Hak (Phraya Pichai of the Broken Sword).

It’s a little simpler as a critic, I find, to write about genre films; theoretically, those kinds of stories have a core of elements that work in similar ways across cultures. That’s far from inevitable — horror, for example, may emerge from wildly different cultural aspects, as does humour — but I’d say it’s broadly true that action movies in particular work well across linguistic and cultural divides. You by and large know what you’re looking for in an action film, and can judge it accordingly. Which brings me to Broken Sword Hero, directed by Bin Bunluerit from a script by Buakaw Banchamek and Phutharit Prombandal. Banchamek also stars as hero Joi (AKA Thongdee); the character’s loosely based on a real 18th-century warrior, Phraya Pichai Dap Hak (Phraya Pichai of the Broken Sword).

The movie begins in Joi’s childhood, when he’s bullied by the son of a local official. He beats up the other child, leading to his exile from his village. This turns him into a wanderer, and as the years pass he becomes strong and swift — but not as skilled as he thinks. As a young man he’s soundly defeated in a fight by a martial-arts master, and this sets him off on a long round of trying to develop himself as a fighter. He gathers friends and a romance subplot in doing so, but the family of the official from his youth are still around to complicate matters. In the end there’s a grand tournament, a threat of war, and a good king in disguise.

I am no expert in 18th century Thai history, and found I did not need to be to enjoy this movie as an action story. There is in fact a fair amount of detail and history involved — the Joi of this movie has some of the characteristics of the historical Joi, such as an aversion to chewing betel nuts — but as an action movie it succeeds without the audience needing to know about the reign of King Thaksin. As far as I can tell, the film is likely more powerful if you do know some of the relevant facts. But I’d be surprised if that knowledge greatly changed the movie’s basic affect. This is a solid, entertaining, and surprisingly warm-hearted action film.

To get to the most important part: the action sequences are varied and inventive, showing off a range of fighting styles. They’re positioned well in the movie, forming natural climaxes, and indicating Joi’s advancement in his studies. They’re shot well, performed well, and staged with real inventiveness if an awful lot of slow motion. This is a fine movie to watch for the sake of watching a martial arts movie, if not exceptional.

What makes the movie stick in my head, though, isn’t just its competence in fight scenes; that’s what you night call necessary but not sufficient. What gives the movie a memorable identity are a few other things. For a start, the setting — the cinematography (so far as I could tell from the screener) does an excellent job of capturing the natural world of the Thai forests. It makes a good background for Joi’s wandering. But there’s more than that.

What makes the movie stick in my head, though, isn’t just its competence in fight scenes; that’s what you night call necessary but not sufficient. What gives the movie a memorable identity are a few other things. For a start, the setting — the cinematography (so far as I could tell from the screener) does an excellent job of capturing the natural world of the Thai forests. It makes a good background for Joi’s wandering. But there’s more than that.

Up above I used the phrase “warm-hearted,” and I think that’s where the film really stands out. Joi’s a genuinely engaging character. Without being at all idealised, he’s a (mostly) happy and a good man — Banchamek is highly believable as a man who does good, not out of deep ideological conviction, but out of an instinctive feeling that you do right by other people. He’s a pleasant and generous hero, if not especially bright. The paradox the film hints at is that he’s also driven to get better at fighting and hurting people. The solution is basically that he’s trying to learn how to stand up for himself and strike back at bullies; I’m not sure how well that holds up in the real world, but in the context of an action film, it suffices.

There’s a kind of sword-and-sorcery minus sorcery feel; perhaps a Thai sword-and-sandal movie might be a better description. Joi wanders about, having adventures, seeking to improve his skills. He gets caught up in bigger things, ultimately being pulled into a more epic political world. It all works, because the world’s been built from the ground up — we’ve seen the villages, we know the people, and what happens at the end matters to us.

There’s a kind of sword-and-sorcery minus sorcery feel; perhaps a Thai sword-and-sandal movie might be a better description. Joi wanders about, having adventures, seeking to improve his skills. He gets caught up in bigger things, ultimately being pulled into a more epic political world. It all works, because the world’s been built from the ground up — we’ve seen the villages, we know the people, and what happens at the end matters to us.

There is an oddly linear sense to the story, to my mind. That might be a function of its basis in history. At any rate, if the villains from early in the film recur and are dealt with rather earlier than one might expect, the bigger problem is that the film has a lot of training sequences in it. Joi moves from teacher to teacher, and if the fight scenes give some sense of his improvement, there’s also less detail than I might have liked. Action doesn’t seem to rise much until the end. There are a lot of incidents, and they mostly come together in the final scenes, but there is an episodic feel, with the passage of time difficult (at least for me) to gauge.

Still, the movie’s too amiable to criticise too harshly. There’s humour here, broad but effective, and a pleasurably relaxed tone. We want to see Joi do well, just because he’s a nice guy. On the basis of Banchamek’s charisma, the film draws us in, makes us root for him, and leaves us happy as he rises in the world. There are worse frameworks for an action movie.

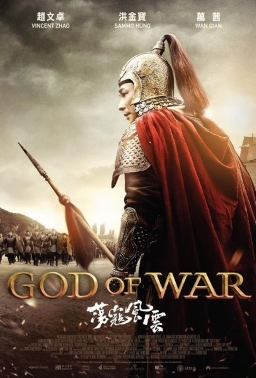

A more elaborate framework awaited me in God of War. Directed by Gordon Chan from a script by Frankie Tam, Maria Wong, and MengZhang Wu, it tells a story of the sixteenth century, when a group of Japanese pirates have taken over some territory on the Chinese mainland. Veteran Chinese general Yu Dayou (played by veteran Chinese action star Sammo Hung) has failed to rout them. Now the siege will be taken over by General Qi Jiguang (Wenzhuo Zhao) — who must also contend with political machinations among his supposed allies.

A more elaborate framework awaited me in God of War. Directed by Gordon Chan from a script by Frankie Tam, Maria Wong, and MengZhang Wu, it tells a story of the sixteenth century, when a group of Japanese pirates have taken over some territory on the Chinese mainland. Veteran Chinese general Yu Dayou (played by veteran Chinese action star Sammo Hung) has failed to rout them. Now the siege will be taken over by General Qi Jiguang (Wenzhuo Zhao) — who must also contend with political machinations among his supposed allies.

Here again we have a historical action movie about real historical figures. In this case, the use of history isn’t as smooth or easygoing as in Broken Sword Hero. The film’s slower than it needs to be, making sure to fit in as much information as it can about its characters and their struggles; and some of that information could usefully be dispensed with.

This is a technically well-made film, with clever camera moves, long tracking shots, and generally high production values. The actors capably handle what they’re asked to do, though I wish more had been asked of Hung, who feels underused. At any rate, the choreography is fluid. Certainly there’s a good eye for composition and colour. And yet the total feels less than the sum of its parts.

Consider the opening shot of the film, a long take flying in over the coast of China to follow a unit of soldiers marching along a road, finally reaching the Japanese fortress. All the while a voice-over gives us a detailed historical background to the siege, explaining why Japanese piracy had become a problem, explaining some of the back-and-forth of the conflict, and yet not actually providing much specific exposition relevant to the siege or the characters involved. When the voice-over stops, a battle scene begins. It’s well-shot, atmospheric, with lots of images emphasising the gore and brutality of the fight, and yet involves fewer intricate maneuvers than one might expect. It feels like a microcosm of the film. It does peripheral things well, but the meat’s lacking.

To my mind, there isn’t really enough non-action character work to qualify the film as a general-purpose historical epic. The focus of the movie is on the battles, as I read it, and it’s not quite complex enough to work as a war film — there’s war in it, but it’s not about war so much as it is about the pageantry of fighting. If it’s far from a standard wuxia movie, it’s perhaps more like a wuxia film than it is like anything else, at least in certain structural terms — it’s not just a question of the number of fight scenes and training montages, but where they come in the movie, and how the characters use fight scenes to establish who they are to the audience and each other. The problem is that on the larger scale, the movie feels as though it’s constantly building to set pieces that don’t always show up.

The film seems to aspire to a greater complexity than it has. It spends a goodly amount of time on the politics behind the Chinese generals, and a lot of time on the motivation of its villains — not just pirates, they’re actually ronin with some vaulting ambition, and they have different factions among them (though, with that established, they do tend to drop out of the movie for extended periods of time). The ingredients for a truly complex film are here, but the plot’s not gripping and the characters too one-note.

The film seems to aspire to a greater complexity than it has. It spends a goodly amount of time on the politics behind the Chinese generals, and a lot of time on the motivation of its villains — not just pirates, they’re actually ronin with some vaulting ambition, and they have different factions among them (though, with that established, they do tend to drop out of the movie for extended periods of time). The ingredients for a truly complex film are here, but the plot’s not gripping and the characters too one-note.

I will say that the pageantry of the movie is remarkable. The costumes, props, and sets build a detailed world, luxurious and precise. The film’s production standards are consistently high, down to the embroidery on the characters’ robes and the artwork in the background. It’s not just that if you’re interested in the details of armour and weaponry, this movie will hold your interest; it’s that, as with the best historical dramas, the mass of background detail gives the movie a consistent visual depth.

And yet the story feels loose, even disjointed, for all the mass of information we get. Qi’s positioned as an inspirational leader, and indeed much of the main conflict of the film involves him trying to raise and train a force of peasant soldiers against the commands of his political bosses — but there’s not much narratively that supports that. A more commanding performance by Zhao might have helped here, but it feels like a deeper void in the script’s also involved.

Oddly, the siege doesn’t remain the kind of focus of the film one might expect. That is, while it’s the nominal point of the story through to the end, there are enough flashbacks and cutaways and battles across country that the location of the fortress doesn’t become the kind of geographical centre you’d expect. You don’t get much of a sense of place, or really of how troops move across the terrain, except in a very general way. In this as in much else, the film feels uncentred.

Oddly, the siege doesn’t remain the kind of focus of the film one might expect. That is, while it’s the nominal point of the story through to the end, there are enough flashbacks and cutaways and battles across country that the location of the fortress doesn’t become the kind of geographical centre you’d expect. You don’t get much of a sense of place, or really of how troops move across the terrain, except in a very general way. In this as in much else, the film feels uncentred.

Add it all up, and you have a watchable movie, but one that’s slow in places where it doesn’t need to be slow. Subplots involving Qi’s wife feel extraneous (though admittedly the film’s lacking in roles for women otherwise) even when they come to affect the main plot, and political maneuverings aren’t especially well-dramatised. But the film’s visually expansive, and when it does do action pieces, it does them well (particularly a battle in a city at about the three-quarter mark). It doesn’t manage to realise its narrative ambitions, and can’t help but feel long. But it gets enough right to be entertaining.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.