Horror or Not: Daphne du Maurier and Rebecca

Women in Horror Month is over now, and after some consideration, I’ve decided to write a bit about a book I didn’t discuss during the month proper, and why it was I didn’t write about it. Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca is often mentioned as a classic horror novel and an important part of the Gothic tradition. I certainly can see it as a Gothic. But I wouldn’t describe it as horror, not exactly. I’d like to try to consider it here, and see if I can figure out just what it is.

Women in Horror Month is over now, and after some consideration, I’ve decided to write a bit about a book I didn’t discuss during the month proper, and why it was I didn’t write about it. Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca is often mentioned as a classic horror novel and an important part of the Gothic tradition. I certainly can see it as a Gothic. But I wouldn’t describe it as horror, not exactly. I’d like to try to consider it here, and see if I can figure out just what it is.

To start with, I can say that Rebecca, published in 1938, was du Maurier’s fifth novel. It became a massive popular success, though critical reception was more mixed. Du Maurier adapted the book for the stage two years later, the same year Alfred Hitchcock’s film adaptation — Hitchcock’s first movie for an American studio — reached screens. Du Maurier herself was thoroughly part of the English literary world; parodied by P.G. Wodehouse, daughter of a famous actor, cousin to the boys who inspired Peter Pan.

The book itself is told in retrospective, as a recollection of the unnamed first-person narrator, who as a young woman in her early twenties falls in love with an older man, Maxim de Winter, marries him, and becomes mistress of his great house called Manderley. But the new Mrs. de Winter finds herself competing against the memories of her husband’s first wife, the eponymous Rebecca. Manderley’s housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers, idolised the dead woman. As the book moves along, we come to find out more about Rebecca and slowly come to understand not only the truth of her relationship with Maxim, but who Rebecca de Winter really was.

When I

When I  I’ve been reading Peter Ackroyd’s writing for almost twenty years now, and I’m frankly beginning to fall behind. It’s hard to keep up with the man: he’s produced poetry, fiction, biographies, creative nonfiction, and, most recently, narrative history. One of his nonfiction books, Albion, was subtitled ‘the English Imagination,’ and was an essay or set of essays investigating exactly that; in fact, much of Ackroyd’s work can be seen as an investigation of, or a struggle with, the nature of English literary, historical, and imaginative traditions — especially as manifested in the history of London. And so his current project (or one of them) is an ambitious six-book history of England. Two have been published so far; as I say, I’m behind, and have only just completed the first, Foundation, examining the past of England from prehistory to the end of the Wars of the Roses.

I’ve been reading Peter Ackroyd’s writing for almost twenty years now, and I’m frankly beginning to fall behind. It’s hard to keep up with the man: he’s produced poetry, fiction, biographies, creative nonfiction, and, most recently, narrative history. One of his nonfiction books, Albion, was subtitled ‘the English Imagination,’ and was an essay or set of essays investigating exactly that; in fact, much of Ackroyd’s work can be seen as an investigation of, or a struggle with, the nature of English literary, historical, and imaginative traditions — especially as manifested in the history of London. And so his current project (or one of them) is an ambitious six-book history of England. Two have been published so far; as I say, I’m behind, and have only just completed the first, Foundation, examining the past of England from prehistory to the end of the Wars of the Roses. Different people have different explanations for why horror fiction exists, and why it’s worthwhile. It’s always seemed to me that, whatever else it does, good horror writing expresses some kind of fear or terror that is both deep and common. Insofar as the fear’s deep, the horror story touches a profound well of emotion, as good fiction usually does; insofar as it’s common the story links readers together and reminds us that we share the same dreads. So at its best, horror fiction is empathic and profound.

Different people have different explanations for why horror fiction exists, and why it’s worthwhile. It’s always seemed to me that, whatever else it does, good horror writing expresses some kind of fear or terror that is both deep and common. Insofar as the fear’s deep, the horror story touches a profound well of emotion, as good fiction usually does; insofar as it’s common the story links readers together and reminds us that we share the same dreads. So at its best, horror fiction is empathic and profound.

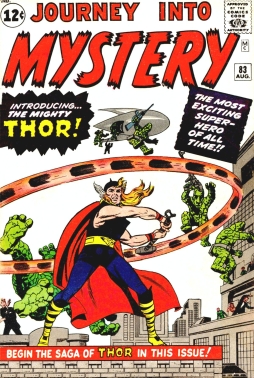

Journey Into Mystery first appeared in 1952, one of a number of anthology titles from publisher Martin Goodman’s line of comic books. Over the years, the title featured a lot of short horror, fantasy, and science fiction tales, many of them collaborations between editor/scripter Stan Lee and artists like Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby. Until 1962. At that point Goodman’s comics were beginning to change direction, following a revival of interest in the super-hero genre. A team book, The Fantastic Four, had taken off. A solo book had followed, The Incredible Hulk. Heroes would now be his company’s main product, and the line would soon come to be known as Marvel Comics. The horror anthology books would be taken over by recurring super-hero characters, and Journey Into Mystery would be the first of the bunch. So with issue 83, in August 1962, in a story credited to Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby, it introduced its new lead: the mighty Thor, Norse god of thunder.

Journey Into Mystery first appeared in 1952, one of a number of anthology titles from publisher Martin Goodman’s line of comic books. Over the years, the title featured a lot of short horror, fantasy, and science fiction tales, many of them collaborations between editor/scripter Stan Lee and artists like Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby. Until 1962. At that point Goodman’s comics were beginning to change direction, following a revival of interest in the super-hero genre. A team book, The Fantastic Four, had taken off. A solo book had followed, The Incredible Hulk. Heroes would now be his company’s main product, and the line would soon come to be known as Marvel Comics. The horror anthology books would be taken over by recurring super-hero characters, and Journey Into Mystery would be the first of the bunch. So with issue 83, in August 1962, in a story credited to Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby, it introduced its new lead: the mighty Thor, Norse god of thunder. Raymond Roussel was a French surrealist writer who died in 1933, aged 56; one of his most famous works, Impressions of Africa, was a self-published novel (later turned into a play) depicting a fantastical African land based on no actual place, which contained a forest called the Vorrh. Late last year, the English sculptor and poet Brian Catling published his second novel, a story based on Roussel’s work: The Vorrh, first of a projected trilogy, described on its back cover as an epic fantasy. It’s a powerful book, precise and unexpected in its use of language and its plot construction, a dizzying and straight-faced blend of history and the unreal.

Raymond Roussel was a French surrealist writer who died in 1933, aged 56; one of his most famous works, Impressions of Africa, was a self-published novel (later turned into a play) depicting a fantastical African land based on no actual place, which contained a forest called the Vorrh. Late last year, the English sculptor and poet Brian Catling published his second novel, a story based on Roussel’s work: The Vorrh, first of a projected trilogy, described on its back cover as an epic fantasy. It’s a powerful book, precise and unexpected in its use of language and its plot construction, a dizzying and straight-faced blend of history and the unreal.

Early on in Sean Howe’s book-length history Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, the reader’s imagination is spurred by a throwaway anecdote: in 1937, New York magazine publisher Martin Goodman and his wife planned to return from a trip to Europe aboard the Hindenburg — on what would turn out to be the final tragic flight of the German dirigible, which ended with a terrifying aerial explosion and fire that led to the deaths of 36 people. Goodman, as it happened, was too late to get tickets and took a plane instead. You can’t help but wonder, though. What if he’d died then, before he’d expanded his magazine line to include comics? Before he’d hired his nephew Stanley to work in the office and do fill-in bits of writing? What if Marvel Comics, the subject of Howe’s book, had been stillborn? What would have been different in the development of comics, of popular culture, of the North American imagination? Maybe everything. Maybe nothing.

Early on in Sean Howe’s book-length history Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, the reader’s imagination is spurred by a throwaway anecdote: in 1937, New York magazine publisher Martin Goodman and his wife planned to return from a trip to Europe aboard the Hindenburg — on what would turn out to be the final tragic flight of the German dirigible, which ended with a terrifying aerial explosion and fire that led to the deaths of 36 people. Goodman, as it happened, was too late to get tickets and took a plane instead. You can’t help but wonder, though. What if he’d died then, before he’d expanded his magazine line to include comics? Before he’d hired his nephew Stanley to work in the office and do fill-in bits of writing? What if Marvel Comics, the subject of Howe’s book, had been stillborn? What would have been different in the development of comics, of popular culture, of the North American imagination? Maybe everything. Maybe nothing.