The House of Ideas that Jack (and Steve) Built: Sean Howe’s Marvel Comics: The Untold Story

Early on in Sean Howe’s book-length history Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, the reader’s imagination is spurred by a throwaway anecdote: in 1937, New York magazine publisher Martin Goodman and his wife planned to return from a trip to Europe aboard the Hindenburg — on what would turn out to be the final tragic flight of the German dirigible, which ended with a terrifying aerial explosion and fire that led to the deaths of 36 people. Goodman, as it happened, was too late to get tickets and took a plane instead. You can’t help but wonder, though. What if he’d died then, before he’d expanded his magazine line to include comics? Before he’d hired his nephew Stanley to work in the office and do fill-in bits of writing? What if Marvel Comics, the subject of Howe’s book, had been stillborn? What would have been different in the development of comics, of popular culture, of the North American imagination? Maybe everything. Maybe nothing.

Early on in Sean Howe’s book-length history Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, the reader’s imagination is spurred by a throwaway anecdote: in 1937, New York magazine publisher Martin Goodman and his wife planned to return from a trip to Europe aboard the Hindenburg — on what would turn out to be the final tragic flight of the German dirigible, which ended with a terrifying aerial explosion and fire that led to the deaths of 36 people. Goodman, as it happened, was too late to get tickets and took a plane instead. You can’t help but wonder, though. What if he’d died then, before he’d expanded his magazine line to include comics? Before he’d hired his nephew Stanley to work in the office and do fill-in bits of writing? What if Marvel Comics, the subject of Howe’s book, had been stillborn? What would have been different in the development of comics, of popular culture, of the North American imagination? Maybe everything. Maybe nothing.

Maybe nothing, because Goodman was not himself involved in any significant way in the creation of the books. The best days for his company came when he let his nephew, by then working under the pseudonym Stan Lee, edit the comics with a free hand — aside from the occasional directive, such as the alleged command ‘those guys across town are doing well with their super-hero team book; you do a super-hero team book too,’ which by one account gave rise in 1961 to The Fantastic Four and to Marvel Comics as we know them. But Goodman himself wrote nothing and drew nothing. If he’d died in 1937, Jack Kirby would have still gone on to a great career. Maybe not with Goodman’s company, but with somebody’s. Steve Ditko as well. You can’t help but think that comics veterans who came to Marvel in the 50s and 60s, Gil Kane and Gene Colan and John Buscema and John Romita and the like, would have found work somewhere. And the next wave of creators, artists like Barry Windsor-Smith and Jim Steranko and Neal Adams, writers like Roy Thomas and Steve Englehart and Steve Gerber, would have made careers in comics for themselves somehow.

But, still, maybe Goodman did change everything after all. Without him, those men (and the smaller number of women who were able to crack Marvel’s boys-club atmosphere) would have done their work, but not necessarily united within a single overall framework, not interlaced into a single fictional universe, their narratives set alongside each other, their stories building on each other, everything contrasting and expanding everything else. Howe’s book, his examination of Marvel across the decades, makes a convincing argument that this creation, this increasingly-complex framework, was not only a new thing, but a key part of Marvel’s success — as well as a handicap the longer the company’s books went on and the more they expanded their roster of titles. And yet, somewhat paradoxically, the biggest problem that emerged for Marvel in Howe’s telling was not the involutions of their overarching continuity, but the further interventions in the creative process by the business owners. The same structures of ownership, copyright, and publication that allowed the Marvel Universe to exist also allowed owners throughout the course of Marvel’s history to interfere with the work of editors and creators, almost always with results ranging from poor to disastrous.

But, still, maybe Goodman did change everything after all. Without him, those men (and the smaller number of women who were able to crack Marvel’s boys-club atmosphere) would have done their work, but not necessarily united within a single overall framework, not interlaced into a single fictional universe, their narratives set alongside each other, their stories building on each other, everything contrasting and expanding everything else. Howe’s book, his examination of Marvel across the decades, makes a convincing argument that this creation, this increasingly-complex framework, was not only a new thing, but a key part of Marvel’s success — as well as a handicap the longer the company’s books went on and the more they expanded their roster of titles. And yet, somewhat paradoxically, the biggest problem that emerged for Marvel in Howe’s telling was not the involutions of their overarching continuity, but the further interventions in the creative process by the business owners. The same structures of ownership, copyright, and publication that allowed the Marvel Universe to exist also allowed owners throughout the course of Marvel’s history to interfere with the work of editors and creators, almost always with results ranging from poor to disastrous.

Before further exploring what Marvel Comics: The Untold Story suggests about its subject, a few words are in order about the book itself. This negative review by a friend of mine makes some good points. The prose isn’t poor but rarely involving in its own right. Few major new revelations emerge, despite detailed research and apparently extensive conversations with former pros. There are nice moments revealing character or the atmosphere at Marvel at a given time, but this story hasn’t really been ‘untold.’ Specifically, it’ll seem very familiar to anyone who’s read Gerard Jones and Will Jacobs’ The Comic Book Heroes. The second edition of the Jones and Jacobs book came out a dozen years ago, so in theory Howe has the advantage of being able to look back at modern Marvel in a way they couldn’t — but in practice he hurries through this final part of his story, in which a large number of previously-unmentioned characters enter his narrative and new themes seem to emerge. It’s a truncated version of recent history. It needed more space, but then again even that might not have helped. In a recent interview Howe said:

There’s room for a sequel, one day, when that history can be told a little more freely. It’s natural that people who are still working in the business don’t want to go on record about the current business that they work on, especially when they’re forced to sign legally-binding non-disclosure agreements at every turn.

Perhaps in part for this reason, Marvel Comics: The Untold Story loses its focus badly in its final stretches. It struggles to cover the machinations that culminate in the company’s bankruptcy, then goes on to describe the financial and creative turns Marvel’s taken in the years since. The business matters are complex, the creative initiatives alternately fascinating and appalling; it all needs room to breathe. And, as I say, this involves introducing a whole new set of characters, while at the same time checking in with older ones, to some extent concluding the story while showing how it’s all still going on.

On the other hand, the earlier parts of the book tell a very familiar story. Pieced together from individuals who were there, and from interviews published in fanzines over the course of decades, the story that emerges is, in its broad outlines, the conventional story of Marvel Comics. Maybe you know some of it. The tale goes more-or-less as follows:

On the other hand, the earlier parts of the book tell a very familiar story. Pieced together from individuals who were there, and from interviews published in fanzines over the course of decades, the story that emerges is, in its broad outlines, the conventional story of Marvel Comics. Maybe you know some of it. The tale goes more-or-less as follows:

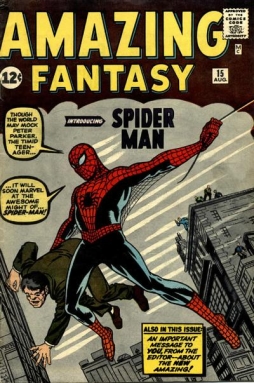

Martin Goodman ran a not-terribly-successful publishing company in the early days of American comics; his biggest commerical comics success, a superhero character named Captain America, was created by a powerful young artist named Jack Kirby. As time went on, Kirby would leave the company for greener fields, and Goodman’s books would shift focus from super-heroes to whatever happened to be in fashion that day. The outfit came to be guided by Goodman’s nephew, Stanley Lieber, AKA Stan Lee. In the late 50s, Kirby returned to the company, joining, among others, a talented artist named Steve Ditko. In 1961, the company, soon to be permanently named Marvel Comics, once again began putting out super-hero comics; propelled by Kirby and Ditko’s art and sense of story structure. Lee’s knack for dialogue and light self-mockery helped sell the books, as did Lee’s creation of a public editorial persona. Through the sixties, the books grew more and more popular, and under Ditko and Kirby broke new ground not only for American commercial comics, but for the medium as a whole. Still, alienated by exploitative working conditions and arguments with management, first one man and then another left. New creators came in, artists and writers who were grown-up fans: some were good, even very good, but the tone of the books changed as they tried with varying degrees of success to address more adult concerns through the form of super-hero comics.

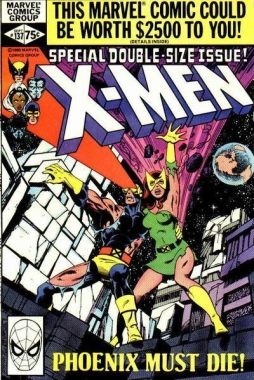

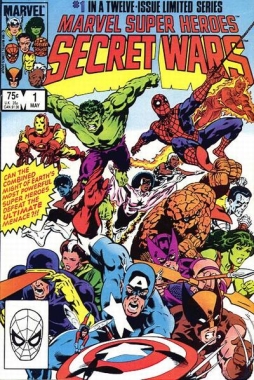

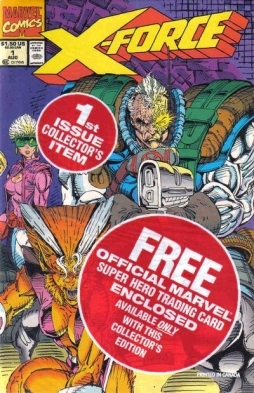

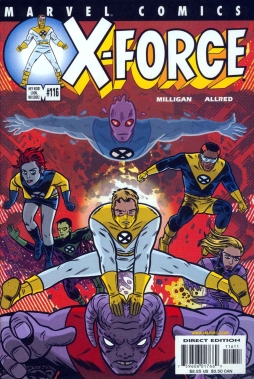

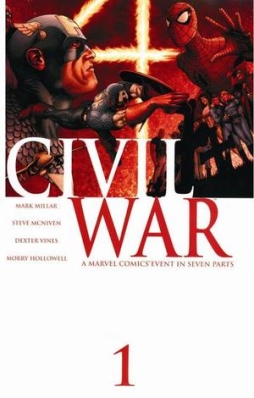

For all the occasional creative breakthrough, deadlines and basic discipline were a problem. The editor-in-chief position became a revolving door. Finally, Jim Shooter was hired as e-i-c, and he made the trains run on time. A revival of an old Kirby book, X-Men, became a huge hit under the guidance of writer Chris Claremont. But meanwhile, Shooter’s micro-management became unendurable, leading to Shooter being forced out. Marvel turned away from innovation, concentrating on ‘plain vanilla’ super-hero books and promoting a new generation of artists — who, in the early 90s, took advantage of new publishing opportunities that previous generations hadn’t had. They left Marvel to create their own company, Image. Marvel flailed creatively, used as a cash cow for its then-current owner, a junk bond king. Finally an unsustainable boom in comics speculation led to a severe market contraction and to Marvel going bankrupt. The company’s recovery from bankruptcy as a creative and commercial force was largely accomplished by new titles and initiatives initiated by the company’s new editor-in-chief, Joe Quesada. At the same time, movie versions of the Marvel characters became huge box-office successes, testifying to their significance to a broader popular culture.

For all the occasional creative breakthrough, deadlines and basic discipline were a problem. The editor-in-chief position became a revolving door. Finally, Jim Shooter was hired as e-i-c, and he made the trains run on time. A revival of an old Kirby book, X-Men, became a huge hit under the guidance of writer Chris Claremont. But meanwhile, Shooter’s micro-management became unendurable, leading to Shooter being forced out. Marvel turned away from innovation, concentrating on ‘plain vanilla’ super-hero books and promoting a new generation of artists — who, in the early 90s, took advantage of new publishing opportunities that previous generations hadn’t had. They left Marvel to create their own company, Image. Marvel flailed creatively, used as a cash cow for its then-current owner, a junk bond king. Finally an unsustainable boom in comics speculation led to a severe market contraction and to Marvel going bankrupt. The company’s recovery from bankruptcy as a creative and commercial force was largely accomplished by new titles and initiatives initiated by the company’s new editor-in-chief, Joe Quesada. At the same time, movie versions of the Marvel characters became huge box-office successes, testifying to their significance to a broader popular culture.

Such is the traditional shape of Marvel history. Howe’s book succeeds not just because it re-tells the story, but also because it leads you into questioning at least some of the details. Was Quesada really a visionary as an editor, or did he simply have access to resources others at Marvel didn’t? Was Lee really the third-most-significant creator at the company in the 60s, or was it his protegé Roy Thomas — who took the books and the idea of a connected universe more seriously than Lee, who recruited the next generation of talent more assiduously, and perhaps was more of an influence on that generation of writers? And was Jim Shooter really a saviour in the late 70s? Was Marvel really in such a poor creative position when he took over, or did his heavy-handed attempt to centralise editorial authority hurt more than it helped? After all, as a direct result of his dictates, writer/editor Marv Wolfman decamped from Marvel to DC, where he revived the Teen Titans and went on to write the first great crossover event mini-series of super-hero comics, Crisis on Infinite Earths; Shooter’s attempts to regulate Marvel’s output led directly to two of DC’s greatest sales success of the following decade.

You can wonder these things because Howe’s not shy about using quotations from numerous sources to present the story. At best, the book’s an oral history of Marvel Comics. And because Howe quotes so many different people, brings out so many points of view, he inevitably gives different perspectives on events. Sometimes recollections are directly contradictory; Rob Liefeld and editor Tom DeFalco remember the 1991 meeting in which Liefeld and fellow-artists Todd MacFarlane and Jim Lee confronted Marvel president Terry Stewart very differently. The meeting led to the trio, and some allies, leaving Marvel and founding Image. It’s a key moment in the recent history of American comics, but, as in the perennial question of who created what in the Lee-Kirby partnership, memories don’t agree. One perception undercuts another. You can’t help but come to question all of them. It’s a strong reminder of the subjectivity of human perception. Howe’s book is a success because at its best it recognises that subjectivity and brings it home for the reader.

You can wonder these things because Howe’s not shy about using quotations from numerous sources to present the story. At best, the book’s an oral history of Marvel Comics. And because Howe quotes so many different people, brings out so many points of view, he inevitably gives different perspectives on events. Sometimes recollections are directly contradictory; Rob Liefeld and editor Tom DeFalco remember the 1991 meeting in which Liefeld and fellow-artists Todd MacFarlane and Jim Lee confronted Marvel president Terry Stewart very differently. The meeting led to the trio, and some allies, leaving Marvel and founding Image. It’s a key moment in the recent history of American comics, but, as in the perennial question of who created what in the Lee-Kirby partnership, memories don’t agree. One perception undercuts another. You can’t help but come to question all of them. It’s a strong reminder of the subjectivity of human perception. Howe’s book is a success because at its best it recognises that subjectivity and brings it home for the reader.

The book becomes part of the process, too. Most of the principals in these stories are still alive, and in writing about events twenty or forty years ago, Howe is writing about stories still being told … and revised. Howe himself notes that details of a conflict between John Byrne and Peter David are still being disputed between the two online. His book becomes another argument put forward, a spur to yet further clarifications and reflections by people directly involved. Since the book’s publication, former Marvel writer Tony Isabella’s been moved to post some memories on his blog. Bob Greenberger, former journalist, DC editor, and Marvel executive, has discussed some issues he found with Howe’s work. Howe himself has created a tumblr as an online supplement for The Untold Story.

I wonder if the book would have been well-served by adding more voices from outside Marvel, close observers with some distance from events — comics journalists, comics retailers, and so forth. In fact, Diana Schutz, former retailer, journalist, and editor for Comico and Dark Horse Comics, is quoted a few times; more would have been nice. You wonder how much industry politics play into what Howe can get people to say, not to mention the legal issues he alludes to in the quote above. Certainly it seems like some of the most interesting material comes from people like Mary Skrenes, who seem not to be much involved in the industry today.

I wonder if the book would have been well-served by adding more voices from outside Marvel, close observers with some distance from events — comics journalists, comics retailers, and so forth. In fact, Diana Schutz, former retailer, journalist, and editor for Comico and Dark Horse Comics, is quoted a few times; more would have been nice. You wonder how much industry politics play into what Howe can get people to say, not to mention the legal issues he alludes to in the quote above. Certainly it seems like some of the most interesting material comes from people like Mary Skrenes, who seem not to be much involved in the industry today.

Still, I found the book overall covered all the bases, painting a complete history of Marvel Comics as a super-hero publishing house. It’s impossible to capture everything; at a certain point you have to choose your details, especially in a print book, where you can’t go on for tens of thousands of words about how Spider-Man’s Clone Saga came to be so badly screwed up. At any rate, for better or worse, Howe’s focus here doesn’t seem to be on the comics themselves.

That is, he doesn’t spend a lot of time evaluating the books Marvel published. Mostly he talks about them only in passing, to establish what was important about a given era or given creator. There’s not much of a discussion of the themes of Marvel’s comics of any era, or much of an attempt to peer into the heads of the various creators. The lack of documentation and the particularly confused collaborative process at Marvel may make that inevitable; there’s only so much you can do, so Howe talks about the books where he can, and spends most of his time on the business end of things: Marvel the publisher. Even so, it has to be a disappointment that there’s only one picture, albeit a powerful picture, in the whole of the book.

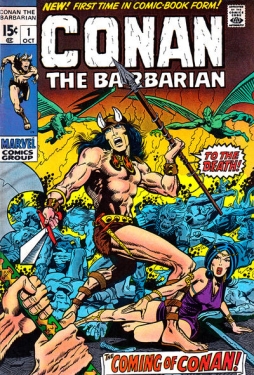

Even more narrowly, Howe tends to deal with Marvel as primarily a publisher of super-hero books. That’s very noticeable in his coverage of the 1970s. There’s effectively no mention of such creative high points as the Roy Thomas and Barry Windsor-Smith Conan, Marv Wolfman and Gene Colan’s Tomb of Dracula, or P. Craig Russell’s Killraven (despite extensive discussion of writer Don McGregor, and McGregor’s work on the Black Panther stories in Marvel Jungle Action). Later, Howe does briefly mention Marvel’s adaptation of Star Wars, but doesn’t discuss their acquisition of the licenses for G.I. Joe or the Transformers — notable, in that G.I. Joe #1 became the first comic advertised on North American TV, while Marvel creators provided the names and backstories for both the G.I. Joe and Transformers characters.

Even more narrowly, Howe tends to deal with Marvel as primarily a publisher of super-hero books. That’s very noticeable in his coverage of the 1970s. There’s effectively no mention of such creative high points as the Roy Thomas and Barry Windsor-Smith Conan, Marv Wolfman and Gene Colan’s Tomb of Dracula, or P. Craig Russell’s Killraven (despite extensive discussion of writer Don McGregor, and McGregor’s work on the Black Panther stories in Marvel Jungle Action). Later, Howe does briefly mention Marvel’s adaptation of Star Wars, but doesn’t discuss their acquisition of the licenses for G.I. Joe or the Transformers — notable, in that G.I. Joe #1 became the first comic advertised on North American TV, while Marvel creators provided the names and backstories for both the G.I. Joe and Transformers characters.

I also felt that one of the pitfalls of Howe focussing on Marvel so intensely was that the larger context of the North American comics industry was sometimes ignored. I can understand why, to a point; again, he has finite space, and there’s no doubt that, for example, the transition of the comics market from newsstands to specialty stores is a complicated topic. But at a certain point, you need to understand the actions taken by other people to understand what was happening with Marvel. When Howe writes about a new level of sophistication entering the Marvel books in the late 90s, for example, he hasn’t discussed the changes in approach to super-hero books generally brought about by people like Alan Moore or Grant Morrison; Watchmen’s not mentioned, nor Marvelman, and The Authority’s referred to only in passing. Similarly, as Howe describes the rise of tie-in crossover books, the absence of any mention of DC’s sprawling Crisis on Infinite Earths becomes almost palpable. You can’t help but notice that when he talks about the watershed works of 1986, comicdom’s annus mirabilis, he doesn’t mention two of the three commonly-cited standout works during that year, Watchmen and Maus; only The Dark Knight Returns, created by former Marvel writer/artist Frank Miller.

I suppose I also would have liked to have seen a little more consideration of Marvel’s impact on popular culture; how it came about, and what it means. There’s a school of thought which holds that the popularity of Marvel comics, and of super-hero comics in general, has to do with their mythic resonance and archetypal nature. My suspicion has always been that it has at least as much to do with the fact that up to my generation, and a good few years after, comics were available everywhere and cost next to nothing — if you were a child in the 70s and early 80s, you could buy a stack of comics however small your allowance money. My point is that I’d have liked to have seen some discussion of what Marvel Comics meant, to readers and to society. How and when and why adults began to pay attention to comics. How the fumbling attempts to film the characters by movie people who Just Didn’t Get It gave way to colossal blockbusters helmed by former comics writers. How a company that sold for 82.5 million dollars in 1987 came to be sold for 4 billion dollars just under a quarter-century later.

I suppose I also would have liked to have seen a little more consideration of Marvel’s impact on popular culture; how it came about, and what it means. There’s a school of thought which holds that the popularity of Marvel comics, and of super-hero comics in general, has to do with their mythic resonance and archetypal nature. My suspicion has always been that it has at least as much to do with the fact that up to my generation, and a good few years after, comics were available everywhere and cost next to nothing — if you were a child in the 70s and early 80s, you could buy a stack of comics however small your allowance money. My point is that I’d have liked to have seen some discussion of what Marvel Comics meant, to readers and to society. How and when and why adults began to pay attention to comics. How the fumbling attempts to film the characters by movie people who Just Didn’t Get It gave way to colossal blockbusters helmed by former comics writers. How a company that sold for 82.5 million dollars in 1987 came to be sold for 4 billion dollars just under a quarter-century later.

Still, with all these caveats, Howe doesn’t shy away from the ugly aspects of his subject. Creators’ rights are a major theme of his book; they have to be, given that in one form or another these issues led so many of Marvel’s most talented and prolific creators to become estranged from the company. Howe covers the basic issues well, including the imposition of work-for-hire contracts in the late 70s. Inevitably, some bits could have used more context — Howe mentions Gene Day’s death, for example, but not the effect it had on a young Dave Sim. I’d have liked to have seen a passing mention of how, long before Image, a generation of talented creators influenced in their youth by Marvel Comics — people like Sim, or Wendy Pini, or Scott McCloud, or the Hernandez Brothers — ended up making careers for themselves elsewhere, as issues of creator ownership became more important.

Overall, on a practical level, even as a lifelong comics reader and occasional critic, I learned some new things from Howe’s book. Like the stuff about Angela Bowie trying to get a Black Widow TV series off the ground in the 70s. Or about some Marvel staffers putting together a cable-access comedy TV show. Or that a fan in Chicago came up with the idea of putting Spider-Man in a black costume. Howe does have the occasional minor slip, as early on when he refers to Mary Jane Watson as ‘raven-haired’. And I wish his attribution had been more consistent; for example, after presenting different accounts of the meeting with Stewart, he doesn’t source his briefer account of a subsequent meeting between the artists and Malibu Comics, who would help get Image off the ground. Generally Howe doesn’t seem to cite information taken from interviews he conducted himself, and while that means he can keep sources off the record, it also means that some material that probably could have been given a source wasn’t.

Overall, on a practical level, even as a lifelong comics reader and occasional critic, I learned some new things from Howe’s book. Like the stuff about Angela Bowie trying to get a Black Widow TV series off the ground in the 70s. Or about some Marvel staffers putting together a cable-access comedy TV show. Or that a fan in Chicago came up with the idea of putting Spider-Man in a black costume. Howe does have the occasional minor slip, as early on when he refers to Mary Jane Watson as ‘raven-haired’. And I wish his attribution had been more consistent; for example, after presenting different accounts of the meeting with Stewart, he doesn’t source his briefer account of a subsequent meeting between the artists and Malibu Comics, who would help get Image off the ground. Generally Howe doesn’t seem to cite information taken from interviews he conducted himself, and while that means he can keep sources off the record, it also means that some material that probably could have been given a source wasn’t.

Howe keeps to a chronological outline for his book, which is a little tricky when you’re discussing runs on a comic title which can last for months or years. At times, he has to cover overlapping events and overlapping creations, meaning that strict chronology has to be abandoned — he seems to prefer, not without reason, to discuss a title’s significance in one place as much as possible. As a result, occasionally the timeline of events becomes difficult to follow, as months or years of work on a title gets conflated into a single mention, but it’s hard to see a better way he could have done it. And, honestly, most of the confusion here is likely to be suffered by longtime comics fans; to most readers, this will seem a lucid presentation of events.

On the whole, Howe provides a real service just by assembling facts and lining them up in such a way that you can draw your own conclusions. Personally, one thing the book made me realise was the centrality of Steve Ditko to Marvel in the early 60s. Not only was he the primary creative force behind what became the company’s most popular comic (Spider-Man) as well as arguably their best (Doctor Strange, if viewed in terms of a series with a clear beginning, middle, and end), but he also designed the sleek red & gold look for Iron Man that still defines the character visually, he came up with the idea of linking the Hulk’s transformations to rage, and he even completed the first issue of Daredevil.

On the whole, Howe provides a real service just by assembling facts and lining them up in such a way that you can draw your own conclusions. Personally, one thing the book made me realise was the centrality of Steve Ditko to Marvel in the early 60s. Not only was he the primary creative force behind what became the company’s most popular comic (Spider-Man) as well as arguably their best (Doctor Strange, if viewed in terms of a series with a clear beginning, middle, and end), but he also designed the sleek red & gold look for Iron Man that still defines the character visually, he came up with the idea of linking the Hulk’s transformations to rage, and he even completed the first issue of Daredevil.

But the man that really emerges over the course of the book as a rounded character is Stan Lee. More precisely, he emerges as a sort of ironically tragic figure, an American failure out of Mamet or Miller (Arthur, that is). To judge by Howe’s account, Lee always wanted something better from his life than to be the creator of pop-culture trash; a desire that led directly, in Lee’s own account, to the creation of The Fantastic Four and the birth of a pop-culture juggernaut. Ultimately, Lee comes off as a man with real artistic and literary ambitions — Howe constantly quotes him talking about leaving comics to write novels or screenplays — but completely lacking the gifts needed to fulfill those ambitions. At the same time, his instincts continually led him to side with his bosses (often also his family) over the artists who did work for him. So although he does come off as genial and warm, he also emerges as a company man.

That seems particularly pointed, as something that returns again and again in Howe’s book is a Mad Men-style (literally; until the 1980s Marvel’s offices were on Madison Avenue) presentation of past culture and especially past corporate culture. It’s not just the boys’-club atmosphere of the old Marvel ‘bullpen,’ but the attitudes of the company’s executives: sweaty little men with delusions of grandeur who tried to demonstrate their godhood by bullying those beneath them. As time moves on, the underlying pathology of power didn’t change, though the manifestation did. Editorial came to serve as a buffer between the businessmen and the creators, but still couldn’t convince the businessmen out of their bad ideas.

That seems particularly pointed, as something that returns again and again in Howe’s book is a Mad Men-style (literally; until the 1980s Marvel’s offices were on Madison Avenue) presentation of past culture and especially past corporate culture. It’s not just the boys’-club atmosphere of the old Marvel ‘bullpen,’ but the attitudes of the company’s executives: sweaty little men with delusions of grandeur who tried to demonstrate their godhood by bullying those beneath them. As time moves on, the underlying pathology of power didn’t change, though the manifestation did. Editorial came to serve as a buffer between the businessmen and the creators, but still couldn’t convince the businessmen out of their bad ideas.

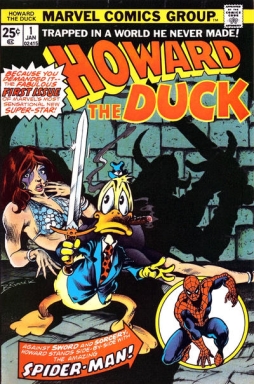

As a whole, is the book worth while? Does it justify spending so much time on its subject? Obviously in a commercial sense, Marvel’s become tremendously significant in North American popular culture. But the company’s also had moments at least of artistic significance, publishing much of the best work of Kirby and Ditko, as well as any number of other important artists — Windsor-Smith, Russell, Gerber’s Howard the Duck, Kurt Busiek and Alex Ross’s Marvels. I’m enough of a comics heretic that I’d argue that the artists of Marvel’s silver age produced greater work during the 60s than their peers in underground comics. And I come away from Marvel Comics: The Untold Story feeling that what is still left untold here is the power of the comics themselves, and what they meant in the history of their medium.

Absent that, we’re left with the ultimately depressing story of men creating incredible comics, then having those comics taken away from them, along with all accompanying characters and copyrights. It’s the story of creators exploited so that more venal men (there are few women in the story Howe tells) can make millions. Not so much an untold story, really, as one we can’t help but wish ends differently. We read, hoping against hope; but there it is, there it always is. Jean Grey gains power, is corrupted, and dies. Jack Kirby’s creations make truckloads of money for faceless men in suits. The burglar who kills Uncle Ben is a man our own actions could have stopped. Steve Ditko cannot control Spider-Man’s destiny. Sometimes greater things come of tragedies. Sometimes they don’t. Sometimes tragedies just become stories, to be told and retold. Better that, at least, than that they be left untold entirely.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

[…] The House of Ideas That Jack and Steve Built: Sean Ho… […]