Arthur C. Clarke on the Moon: A Fall of Moondust and Earthlight

A Fall of Moondust by Arthur C. Clarke; First Edition: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1962.

Cover art Arthur Hawkins. (Click to enlarge)

A Fall of Moondust

by Arthur C. Clarke

Harcourt, Brace & World (248 pages, $3.95 hardcover, 1962)

Cover art by Arthur Hawkins

Earthlight

by Arthur C. Clarke

Ballantine (186 pages, $2.75 hardcover, 1955)

Cover art by Richard Powers

Arthur C. Clarke is best known for his visionary, philosophical tales of human destiny, with their explorations of the depths of time and space, their brushing contact with godlike aliens: Childhood’s End, The City and the Stars, “The Star,” “The Nine Billion Names of God,” and of course 2001: A Space Odyssey. But another type of story turns up regularly throughout his career: the near-term technological puzzle story. Prelude to Space (covered here) has its philosophical overtones, but is basically about the technical and political issues of launching a rocket to the moon. And of course the center section of 2001 is all about diagnosing a malfunctioning part, and dealing with a malfunctioning supercomputer. Famous early stories like “Technical Error” and “Superiority” dealt with issues of problematic future technology.

Clarke’s 1962 novel A Fall of Moondust is very much a story of technical problems and how they are solved (and the resolution is a happier one than those in the other titles just mentioned). Specifically, it’s about a search and rescue mission, anticipating the spate of “disaster” movies (and associated novels) about groups of civilians trapped in some situation (burning skyscraper, disabled passenger jet, and so on) and the parallel efforts of rescuers to save them, that were popular especially in the ‘70s. (In fact, Wikipedia notes this novel’s similarity to a 1978 film about a stranded submarine, Gray Lady Down.)

The premise of Moondust involves what some scientists were worried about back before the earliest probes reached the Moon (the first one was the Soviet Luna 2, in 1959). What if the smooth areas of the lunar surface, those “maria,” were seas of fine dust? So fine that a spacecraft attempting to land there might simply sink into the dust and vanish? Clarke had speculated about this at least once before, in Earthlight, his 1955 novel, covered briefly below; in Moondust the central premise is that yes, the seas are areas of dust so fine they can be “sailed” upon.

Gist

A tourist ship sinks into a sea of dust on the Moon and the narrative follows the efforts of the ship’s crew to keep the passengers alive, and of rescuers on the surface to reach and rescue them. Which they do.

Take

This is as suspenseful a novel as I think Clarke ever wrote, and though its central premise turned out to be wrong (fortunately), the problem and its solution are clearly laid out and dramatically narrated.

Summary

A Fall of Moondust by Arthur C. Clarke; Gollancz/SF Masterworks, 2002

Cover art Fred Gambino. (Click to enlarge)

Page references are to the SF Masterworks edition, shown here. Appropriately for its story, the narrative here is third-person author omniscient, the POV moving smoothly from one situation or set of characters to the next, like an outline for a film script, while sometimes stepping outside the story for some typical Clarke cosmic overview.

On the Moon—

- The setting is a colonized Moon, where “the only boat on the Moon” is the Selene, a surface vehicle that skims across the (fictional) Sea of Thirst, a large area of very fine dust, powered by electrically driven blades (like paddle-wheels). Captained by Pat Harris, who is assisted by Sue Wilkins, it carries 20 passengers on a tour out into that sea.

- As Sue narrates, the ship comes to the Inaccessible Mountains in the middle of the sea with a “Crater Lake” in the center. The boat enters and circles the Crater Lake. As it exits the lake, an underground bubble of ancient gas begins to burst — here Clarke steps back from the characters to provide some cosmic perspective, p18: “For a million years the bubble had been growing, like a vast abscess, below the root of the mountains” — which as it bursts, forms a funnel in the dust that the Selene encounters and drops into, abruptly sliding downward, until it’s completely covered by the dust.

On Earth and in Space—

- Traffic Control on Earth notes that the automatic signal from the Selene has cut off. The engineers there become concerned, even alarmed, but they have only a general idea of where the boat was, in that sea. Did it explode? Hit an obstacle?

- On Lagrange II, a satellite poised at a gravitational balance point between Earth and Moon, astronomer Thomas Lawson gets a priority red signal, waking him. He turns his 100-centimeter telescope to the Lunar surface, but sees nothing.

Aboard Selene—

- The Selene comes to rest, under the dust. A passenger lights a cigarette (!) until Harris frowns at him. Harris ups the pressure against that of the dust. They have only a week of oxygen. He worries that they left no trace on the surface.

- And then one of the passengers introduces himself as Commodore Hansteen — famous for having led the first expedition to Pluto, among many other trips — traveling under an alias. Harris is relieved to have another leader on hand.

- (Meanwhile on Langrange II, Tom Lawson takes photographs of the moon, looking for any trace. And Father Vincent Ferraro, selenophysicist, notes data about a lunar quake.)

- Harris briefs the passengers, worried about their boredom as much as anything. He has them gather available books, and has them introduce each other. There are quite a few technical experts, including a Dr. McKenzie, an Australian physicist. Harris suggests creating a deck of cards, or staging a play. McKenzie expresses concern about the heat — they may not last a day.

- (Meanwhile dust-skis pass by overhead on the surface, seeing nothing, and head for Crater Lake, where, seeing evidence of massive landslides, they call off the search in the Sea of Thirst, presuming that Selene is buried by a landslide.)

- Inside the boat, temperatures rise. The passengers prepare for sleep, and remove outer clothing.

- Dawn. Harris hears a faint sound — the sound of dust shifting, and they realize the heat is percolating up thru the dust, so they’re not getting as hot as feared.

On the Moon, Clavius City—

- In Clavius City, officials presume everyone is dead if the ship was trapped in a slide, and worry about how much it will cost to dig them out. The Chief Engineer, Robert Lawrence, writes a report giving estimates, using an “electrosecretary” referred to as she.

- And then Lawson, the astronomer, calls. He took an infrared photo of the sea after all (despite the search there being called off), and found a trail leading out of the Crater Lake back out into the Sea of Thirst — and ending.

Aboard Selene—

- In the morning the Selene group chooses a book to read, out of two available: an edition of Shane that begins with an introduction about how the classic western novel appeals to those who travel space, in a long introduction that Clarke imagines across a full page:

- “… During the last few years, however, a reaction has set in. I am creditably informed that Western stories are among the most popular reading matter in the libraries of the space-liners now plying between the planets. Let us see if we can discover the reason for this apparent paradox — the link between the Old West and the New Space.”

- Chief Engineer Lawrence speaks with Lawson, taking an instant dislike to the younger man for his arrogant attitude when speaking to non-scientists. But he listens, and after some further calls, decides he needs Lawson on hand.

In Space—

- The cargo-liner Auriga is diverted to Lagrange II to pick up Lawson. On board is a newsman, Spenser, who wonders what’s going on, and pumps Lawson a bit.

Aboard Selene—

- The passengers celebrate someone’s birthday, and someone poses the quiz about how many people are needed to guarantee a 50% chance of sharing a birthday. And then they hold a “court,” where a chosen prosecutor asks another passenger their real reasons for coming the Moon. That is, they keep themselves busy. Yet Commodore Hansteen watches them all, wondering who will be the first to crack.

On the Moon—

- Lawson arrives on the Moon, is given instructions going out on the surface in “sleds” with his IR detector, and heads out with Lawrence.

- Lawson compares an infrared version of Earth, compared to the visual, and wonder which is real, if either, p77: “It was a reminder of the fact, which no scientist should ever forget, that human senses perceived only a tiny, distorted picture of the Universe.”

- Meanwhile Spenser contacts the cargo ship’s Captain Anson, fishing for info — is all this about that missing boat?

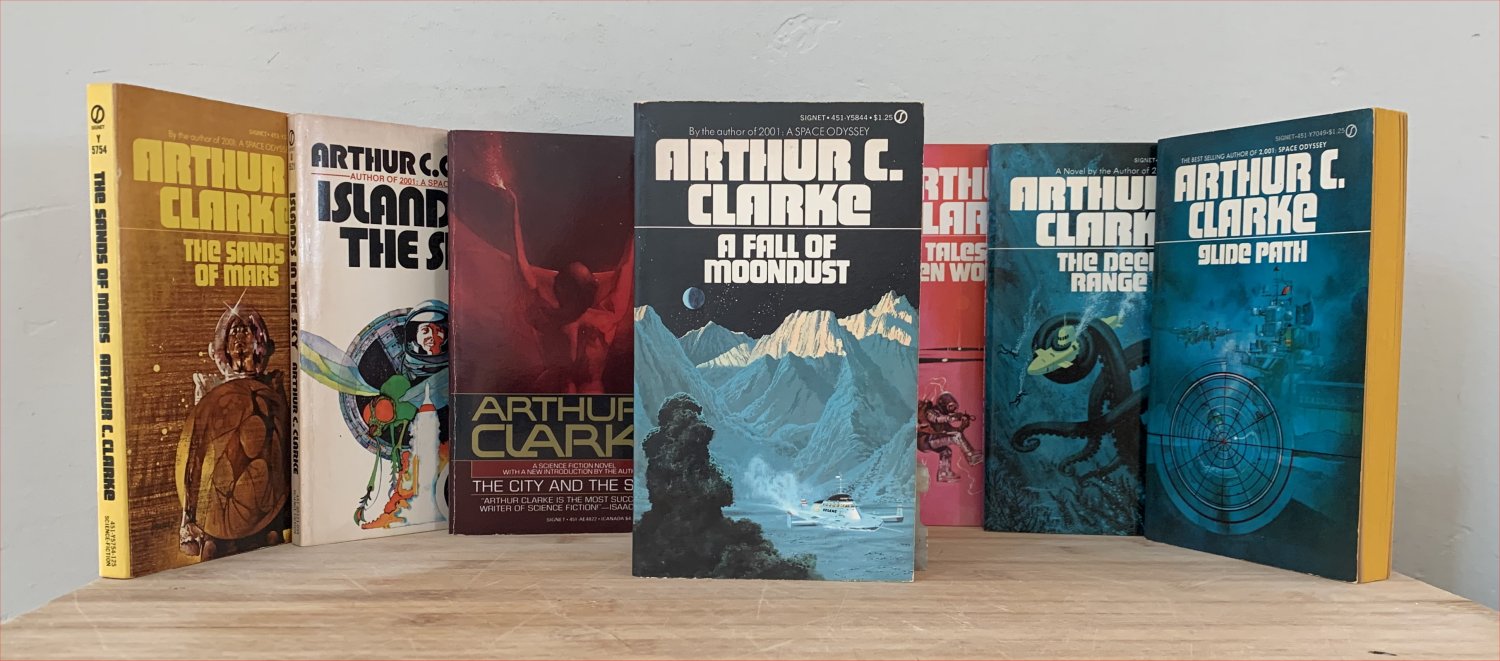

In the center: A Fall of Moondust by Arthur C. Clarke; Signet, 1974

Cover art Dean Ellis. With other contemporaneous Signet editions of Arthur C. Clarke books:

The Sands of Mars (first ed. 1952; Signet 1974); Islands in the Sky (1st 1952; Signet date unknown);

The City and the Stars (1st 1956; Signet 1987); Tales of Ten Worlds (1st 1962; Signet 1973);

The Deep Range (1st 1957; Signet 1974); Glide Path (1st 1963; Signet 1973)

(Click to enlarge)

(From this point I’m abandoning strict chronological order of plot points, but rather grouping them by situation… Clarke effectively switches back and forth between those on the boat, and the rescuers, in cinematic fashion, gradually ratcheting up the tension. You *know* Selene’s occupants will be saved, but how? And how many different things can go wrong before they are?)

Search and Rescue—

- Lawrence and Lawson, on their sleds, reach the target area, finding, despite the mottled IR pattern, the suspect spot. They lower a probe through the dust and hit something, 15 meters down.

- Spenser, the reporter, makes an arrangement with the pilot of the cargo ship, Auriga, to relocate the ship to the foothills overlooking the site of the Selene. Spenser plans to broadcast the rescue effort live.

Aboard Selene—

- The passengers move on to reading the second book, a racy one. Pat Harris and Sue Wilkins give in to their mutual attraction and embrace, privately.

- And then they hear a scraping, and realize they have been found. They tap a signal back, like the first four notes of Beethoven’s 5th. Harris uses the radio, and quickly pics up the two on the sleds above them. They use the pole to conduct radio waves.

- Contact established, the passengers take turns sending various messages to friends and loved ones.

Search and Rescue—

- Lawrence, now in charge of the actual rescue, forms a committee to brainstorm ideas. Hare-brained ideas come in from the public about ways to save the ship’s passengers and crew, as Lawson takes them down: blow the dust away with air (air from where?), freeze the dust with water (water from where?) and drill through it?

- Lawrence’s men create a mock-up of Selene’s roof to test poking or drilling through it. Meanwhile a crew heads out to construct a base at the site of the rescue.

- Spenser worries about the issue of falsely adding stars to the view for his news report visuals, p153, which is done using a “Star Gate circuit.” As he sees rescue crews arrive at the site, he turns on his camera, and live TV coverage begins.

Aboard Selene—

- It gets hard to breathe, and they realize they’re succumbing to CO2 poisoning. Cpt. Harris explains to the passengers that they need to use “sleep tubes” to put them to sleep for 10 hours, to make their oxygen last longer. Harris and McKenzie stay awake, to keep watch. The base plays them Berlioz’ Rákóczi March (Clarke spells it Rakoczy) at high volume.

- There’s a long aside about McKenzie, the Australian physicist, and his name, since he’s actually Abo, only implicitly revealed before now — with discussion of how the native Australians are no less intelligent than Europeans, just with different background experiences (quotes below).

- A harpoon is lowered from the surface to drill thru the roof of the ship, into the cabin. Harris, groggy, uses a wrench to unscrew the end, even when told to stop, and unseals the harpoon prematurely, causing all the air to rush out of the cabin, until he instinctively grabs a book and blocks the hole.

Search and Rescue—

- Spenser sees what look like an eruption. The rescuers quickly get oxygen flowing into the ship, and Cpt. Harris and McKenzie revive, then perform artificial respiration on the others. A second tube follows.

- Rescuers arrive to set up an “igloo” at the rescue site, inside of which Lawrence gets out of his space suit.

- The planned rescue method entails lowering a caisson (I had to check exactly what a caisson is) to attach to the outside surface of Selene, and drill a hole through the hull. Complications ensue: the boat keeps sinking slightly; as it does the air pipes rip out, and dust pours in; and the radio rips out and can’t be repaired, so communication is lost.

Aboard Selene—

- Meanwhile, a reclusive passenger, Radley, who hasn’t said much yet, stands up to explain that all of this is his fault. It’s because “they” are after him — the flying saucers that have been seen for centuries, kept secret by a conspiracy of scientists and astronauts. Startled, Harris and the others let him talk. Radley goes on about conspiracy theories, and Clarke provides some background about how the “Flying Saucer religion” raged and then faded, but never completely, p193. Radley of course has an answer for every objection. Finally, another passenger, Harding, stands up to announce that he’s a detective, following Radley, an accountant who’s made off with stolen credit.

- And then they hear another drill coming through roof, with a speaking tube.

Search and Rescue—

- Spacesuit removed, Lawrence descends into the caisson, then turns screws to unfold a piece of tubing to extend to Selene’s hull. He removes the plate he’s standing out and buckets out the remaining dust.

- Could anything else go wrong? Yes! One of the passengers inside Selene sees that they’re on fire — behind the toilet, one of the power cells is on fire.

- Lawrence uses a silicon gun to inject into the hull to seal the dust between its layers. Then he has to wait 5 minutes for it to dry. He positions a ring-charge to blow open the hole.

- Inside, dust seeps in from the fire compartment. Once the escape path is open, everyone inside Selene ascends a ladder in alphabetical order, as the door behind them bursts and dust floods the inside of the boat. They all get out, as below them the lox tanks blow and explode the boat. Everyone is safe on the surface.

- And Cpt. Harris bursts into tears.

Years Later—

- Harris pilots Selene II away from port, while Sue, now pregnant, stays behind. He walks back through the cabin, greeting passengers. He’s planning to enter space service and leave the moon. Lawrence is writing a book. Lawson is famous. Harris looks out the window, at the stars, and expects to see them more brightly the next time.

Notes and Quotes

- P129, Tom Lawson reflects on his education, one “which, a century earlier, only a few men could afford. … Such treatment was automatic in this age, when every child was educated to the level that his intelligence and aptitudes permitted. Now that civilization needed all the talent that it could find, merely to maintain itself, any other educational policy would have been suicide.”

- Over three pages, beginning p144, Harris and McKenzie discuss the latter’s background as an Australian aboriginal:

[McKenzie] “I’m an Australian first, and an aboriginal second. But I must admit that my white countrymen were often pretty stupid; they must have been, to think that we were stupid! Why, way into the last century some of them still thought we were Stone Age savages. Our technology was Stone Age, all right — but we weren’t.”

[Harris] “If your people weren’t in the Stone Age, Doc — and just for the sake of argument I’ll grant that you aren’t — how did they whites get that idea?”

[McKenzie] “Sheer stupidity, with the help of a preconceived bias. It’s an easy assumption that if a man can’t count, write, or speak good English, he must be unintelligent. I can give you a perfect example from my own family. My grandfather — the first McKenzie — lived to see the year 2000, but he never learned to count beyond ten. And his description of a total eclipse of the Moon was ‘Kerosene lamp bilong Jesus Christ he bugger-up finish altogether.’

“Now, I can write down the differential equations of the Moon’s orbital motion, but I don’t claim to be brighter than grandfather. If we’d been switched in time, he might have been the better physicist. Our opportunities were different — that’s all. Grandfather never had occasion to learn to count, and I never had to raise a family in the desert — which is a highly-skilled, full time job.”

- P153, Spenser’s news photographer ponders: “The public expected to see stars in the lunar sky even during the daytime, because they were there. But the fact was that the human eye could not normally see them; during the day, the eye was so desensitized by the glare that the sky appeared an empty, absolute black. … But the TV camera could [see them], if desired, and some directors preferred it to do so. Others argued that that falsified reality; it was one of those problems that had no correct answer.” (I think 2001 fibbed on this matter too.)

- P192ff, Radley’s conspiracy mongering sounds, alas, exactly like those today. He has an answer for everything…

“You still haven’t explained to us,” Mr. Schuster was now saying, “why the Saucer people should be after you. What have you done to annoy them??

“I was getting too close to some of their secrets, so they have used this opportunity to eliminate me.”

“I should have thought they could have found less elaborate ways.”

“It is foolish to imagine that our limited minds can understand their mode of thinking. But this would seem like an accident; no one would suspect that it was deliberate.”

And so on, and on.

Earthlight

Earthlight by Arthur C. Clarke; First Edition: Ballantine, 1955.

Cover art Richard Powers.

This earlier 1955 novel is perhaps the most similar of Clarke’s other novels to Moondust. For one, they’re both set on the Moon, and both a couple hundred years in the future, when colonies have been established on Mars and Venus. Second, both involve outsiders coming to the Moon that serve as witnesses to the action. In Moondust it was the reporter Spenser; in Earthlight it’s the main character, Bertram Sadler. Summarizing the key points and plot:

- Bertram Sadler, supposedly an accountant, comes to the Moon to audit the big telescope there (which, coincidentally, has just discovered a new supernova). Actually he’s a secret agent, on the hunt for a spy. Earth stands in opposition to the Federation of Mars and Venus, who resent Earth’s monopoly of mineral resources. Now, the news has leaked out that such resources have been discovered on the Moon. Who’s leaking the news?

- Sadler befriends various members of the observatory’s staff; he visits the nearby Central City, a dome large enough to generate actual rain.

- Meanwhile, unknown ships are landing on the lunar surface not far from the observatory. Their mission turns out to be friendly, but secret: a government project to 1) manipulate magnetic forces to dig a hole a full 100 km into the lunar surface, to access those valuable mineral resources, and 2) develop some super-secret weapon.

- The climax of the book, ¾ of the way through, is The Battle of Pico, named for the nearby lunar mountain (real in this case, unlike the fictional mare in Moondust). It begins as three Federation ships, moving and maneuvering improbably fast, appear and attack the secret government installation, which responds by turning its dome into a perfectly reflective mirror, and shooting huge beams (of what?, two eyewitnesses wonder) into space, literally splitting two of the attacking ships apart.

- The third attacking ship escapes and calls Mayday to a passenger vessel on its way to Mars, which rescues most of its crew, even as the crew has to leap, without spacesuits, the short distance from one ship to the other in raw vacuum.

- The results of the brief war is a stalemate, and a treaty, with the Federation gaining access to the lunar minerals, and Earth gaining access to the “accelerationless” drive the Federation used in their attack. The implication is, as in the American revolution, both sides will benefit in the long run.

- Thirty years later Sadler returns to the Moon and seeks out the man who he suspected, but never proved, was the spy: Molton, a spectographer and coincidentally the first astronomer Sadler met when he first arrived on the moon, riding the Monorail and admiring the Earthlight. Molton explains how he got his signals out (using the telescope itself) and defends his actions ambiguously with a quote from a French statesman, Tallyrand: “What is treason? Merely a matter of dates.”

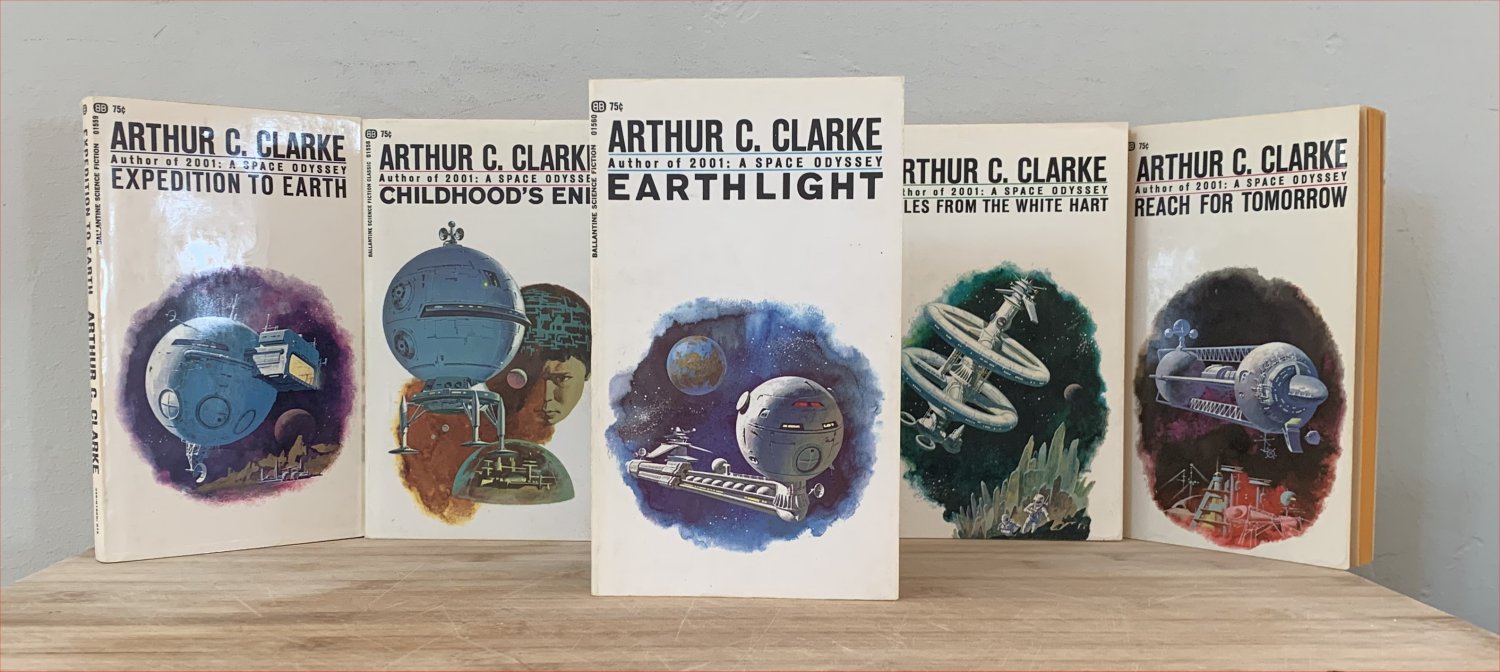

In the center: Earthlight by Arthur C. Clarke; Ballantine 5th printing, 1969

Cover art uncredited, possibly Vincent Di Fate.

With other Ballantine editions of Arthur C. Clarke books, March 1969 printings

with cover art obviously inspired by 2001: A Space Odyssey:

Expedition to Earth (first ed. 1953); Childhood’s end (1st 1953);

Tales from the White Hart (1st 1957); Reach for Tomorrow (1st 1956);

(Click to enlarge)

Comments—

- There are at least three ideas here that foreshadow later Clarke works:

- The astronomers, discussing the newly discovered supernova, speculate that it might well have wiped out a civilization. This of course anticipates Clarke’s famous short story “The Star,” published later in 1955. Page 18: “It was a heart-freezing thought. At any moment, as likely as not, somewhere in the universe a whole solar system, with strangely peopled worlds and civilizations, was being tossed carelessly into a cosmic furnace. Life was a fragile and delicate phenomenon, poised on the razor’s edge between cold and heat.”

- The notion of lunar dust being so fine one would sink right into it is used here, frankly, as a plot device to strand two of the observatory staff near enough to the secret installation to witness the Battle of Pico themselves, giving Clarke POV characters. In the intro to the SF Masterworks edition of Moondust Clarke acknowledges the early use of the idea, but claims no originality, citing an earlier work by James Blish.

- Finally the idea that men could survive brief exposure to the vacuum of space (which Clarke also attributes, elsewhere, to another earlier writer, Stanley Weinbaum) turns up in, of course, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

- The battle scene is quite spectacular, as the two hapless eyewitnesses see, in perfect silence, various bizarre energy weapons hurtling back and forth, and their effects: the secret installation dome turning to a mirror; the rock around it turning molten; the strange beams shooting into the sky, which they realize can’t be energy of whatever wavelength or it wouldn’t be visible. (Clarke tells us, from authorial omniscience, that it was “a jet of molten metal” powered by those magnetic forces.) And then as the powerful magnetic forces that generate both the “beams” and support the 100 km deep well into the lunar surface collapse… the whole facility blows its top, shooting masses of silicon into the sky.

Mark R. Kelly’s last review for us was of Philip K. Dick’s Eye in the Sky and two others. Mark wrote short fiction reviews for Locus Magazine from 1987 to 2001, and is the founder of the Locus Online website, for which he won a Hugo Award in 2002. He established the Science Fiction Awards Database at sfadb.com. He is a retired aerospace software engineer who lived for decades in Southern California before moving to the Bay Area in 2015. Find more of his thoughts at Views from Crestmont Drive, which has this index of Black Gate reviews posted so far.