The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes: The Truth About Sherlock Holmes (Doyle on Holmes)

I have about 500 Holmes/Arthur Conan Doyle-related books on my shelves. No surprise, there are some pretty neat things. I’m going to do a couple posts over the next few weeks, looking at some things written by Doyle – or directly involving him.

I have about 500 Holmes/Arthur Conan Doyle-related books on my shelves. No surprise, there are some pretty neat things. I’m going to do a couple posts over the next few weeks, looking at some things written by Doyle – or directly involving him.

The first is in my copy of Peter Haining’s The Final Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. It’s a really nifty book put out by Barnes and Noble in 1995 (with Jeremy Brett on the cover). If you don’t have a copy of Jack Tracy’s essential The Published Apocrypha, this has several items included in that hard-to-find classic. It’s also got some additional things including a really cool essay by Doyle.

In 1923, Arthur Conan Doyle wrote The Truth About Sherlock Holmes, for Collier’s Magazine.

In 1903, Collier’s offered Doyle big money to write new Sherlock Holmes stories. Doyle had set The Hound of the Baskervilles back before tossing him over the Reichenbach Falls. So, Holmes was still dead. It was too big an offer to refuse, and Doyle agreed to write eight new stories. They all appeared in Collier’s, and then immediately after in The Strand. Colliers included terrific color covers by Frederic Dorr Steele.

It’s Elementary – I wrote an essay on Frederic Dorr Steele

The ensuing five stories, which are included with the first eight in The Return of Sherlock Holmes, debuted in The Strand.

Collier’s ran the essay in the December 29th issue of The National Weekly, which they owned.

One hundred-and-one years later, we know an incredible amount about Doyle’s creation of, and thoughts about, Holmes. But this was terrific stuff at the time. Doyle used some of these facts in his autobiography, Memories and Adventures.

THE INSPIRATION FOR HOLMES

Doyle starts out talking about being a medical student at the University of Edinburgh in October of 1876. There was a surgeon/instructor named Joseph Bell, whose “strong point was diagnosis, not only of disease, but of occupation of character.”

Doyle tells how he became Bell’s clerk, and relates an incident of the doctor making observations of a patient in the style which would become Holmes’ trademark. As Doyle related,

“It is no wonder that after the study of such a character I used and amplified his methods when in later life I tried to build up a scientific detective who solved cases on his own merit and not through the folly of the criminal.” He adds humorously, “Bell took a keen interest in those detective tales and made suggestions, which were not, I am bound to say, very practical.”

A WRITER IS BORN

Doyle compressed the first-year classes into a half-year so he could try to earn some money. He was given twopence a day for lunch (the price of a mutton pie). But he often went to a second-hand bookshop and got an old book for the price. A friend had told him that his “letters were very vivid,” and surely he could write some things to sell.

Readers often aspire to be writers (I became one). Doyle sat down and wrote “The Mystery of Sasassa Valley” and sold it to Chambers’ Journal.

Graduating from medical school, he got some practical experience by serving as ship’s doctor along the west coast of Africa. Then he opened an office in Portsmouth. He sold some stories for extra money, as being a doctor was not profitable. He made very little money, but he said he still had notebooks full of all sorts of knowledge which he acquired during the time. “It is a great mistake to start putting out cargo when you have hardly stowed any on board.” An insight on his approach to writing.

ENTER HOLMES AND WATSON

Dismissing his first attempt at a novel – The Firm of Girdlestone – as “a worthless book,” he felt capable of “something clear and crisper and more workmanlike.” As he said:

“Gaboriau had rather attracted me by the neat dovetailing of his plots, and Poe’s masterful detective, M. Dupin, had from boyhood been one of my heroes. But could I bring an addition of my own?”

Has EVER a question been so definitively answered after the fact?

“I thought of my old teacher Joe Bell, of his eagle face, of his curious ways, of his eerie trick of spotting details. If he were a detective he would surely reduce this fascinating but unorganized business to something near to an exact science. I would try if I could get this effect. It was surely possible in real life, so why should I not make it plausible in fiction? It is all very well to say that man is clever, but the reader wants to see examples of it – such examples as Bell gave us every day in his wards.”

Dashiell Hammett revolutionized detective fiction (I have written about Carroll John Daly writing the first hardboiled detective. Set aside Three Gun Terry Mack and Race Williams for a moment, please). Hammett took crime from English country manors and put it on the mean streets of then-contemporary America. From poison to gats. Along with the other pioneers of the hardboiled school, he completely changed private eye fiction.

Dashiell Hammett revolutionized detective fiction (I have written about Carroll John Daly writing the first hardboiled detective. Set aside Three Gun Terry Mack and Race Williams for a moment, please). Hammett took crime from English country manors and put it on the mean streets of then-contemporary America. From poison to gats. Along with the other pioneers of the hardboiled school, he completely changed private eye fiction.

Doyle, with this entirely new way of writing a British mystery, did the same, decades before. This was light years from Collins’ The Moonstone, or even Poe and Gaboriau (Doyle was taken to task for Holmes’ comments on his real-life predecessors. I’ll write about that in another essay).

Now, this was written long after the creation of Holmes, of course, And we naturally reshape our memories over the years. But here is Doyle citing Bell as the example of a systematic approach to a new type of detective.

He wanted a common name, and Sherringford Holmes became Sherlock. He needed “…a commonplace comrade as a foil – an educated man of action who could both join in the exploits and narrate them. A drab, quiet name for this ostentatious mane. Watson would do.”

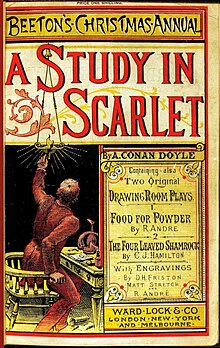

Doyle had expected Girdlestone to circle back “with the precision of a homing pigeon.” But he was hurt when A Study in Scarlet suffered the same rejection. James Payn (who had published that first story in Chambers’) applauded it but found it both too short and too long: which Doyle agreed with. Arrowsmith sent it back unread. A few others declined it before Ward, Lock & Co. made an offer on October 30, 1886:

“DEAR SIR – We have read your story and are pleased with it. We could not publish it this year, as the market is flooded at present with cheap fiction, but if you do not object it to its being held over till next year, we will give you twenty-five pounds for the copyright.”

It’s Elementary – ‘Flooded with cheap fiction’ is not exactly a glowing acceptance phrase.

It’s Elementary – ‘Flooded with cheap fiction’ is not exactly a glowing acceptance phrase.

Doyle called it a not very tempting offer, both for the small sum, and for the delay in printing. But he felt something was better than nothing, and it became Beeton’s Christmas Annual of 1887.

As Doyle explains, because of that short novel, he found himself at a publishers’ dinner, which led to The Sign of the Four.

It’s Elementary – In April of 1889, the editor of Lippincott’s magazine talked with both Doyle and Oscar Wilde, pursuant to establishing a British version of the publication. He commissioned Doyle to write The Sign of the Four, while Wilde wrote The Picture of Dorian Gray.

Doyle then talks about The White Company (written after The Sign of Four) and Sir Nigel. He always considered them much better than Holmes. As he says:

“…they form the most complete, satisfying, and ambitious thing that I have ever done. All things find their level, but I believe that if I had never touched Holmes, who has tended to obscure my higher work, my position in literature would at the present moment be a more commanding one.”

I’ve always felt that Doyle was a bit of a pretentious twit. He wrote other novels, and Brigadier Gerard, and The Lost World books, still have popularity in certain circles. But I find The White Company and Sir Nigel slow reads. The only Doyle I really like is Holmes. If not for the Baker Street sleuth, I wouldn’t read any Doyle. This whole ‘he holds me back’ stuff sounds like the know-it-alls who look down on fantasy, or Pulp, as somehow of less merit because it’s not ‘literature.’

THE STRAND

So, with The White Company done and having left Southsea for London, Doyle assessed the recent development of monthly magazines, running unconnected stories (as opposed to serials). In his own words again:

“…it had struck me that a single character running through a series, if only it engaged the attention of the reader, would bind that reader to that particular magazine.”

Again, you’ve got a very shrewd, insightful, writer. He studied the prior literature in developing Holmes as a new variant. He studied the market in hitting upon the idea of a central character having unrelated adventures, to increase a specific magazine’s sales. Which of course, would increase his pay.

Again, you’ve got a very shrewd, insightful, writer. He studied the prior literature in developing Holmes as a new variant. He studied the market in hitting upon the idea of a central character having unrelated adventures, to increase a specific magazine’s sales. Which of course, would increase his pay.

Having already written two stories about Holmes, he saw the detective lending himself “to a succession of short stories.” With lots of free time in his unvisited consulting room, he wrote Holmes stories, which Strand editor Greenhough Smith happily bought.

Success achieved with the stories which would be collected together as The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Doyle dropped the expensive doctor job and focused on writing for a living.

“The difficulty of the Holmes work was that every story really needed as clear-cut and original a plot as a longish book would do. One cannot without effort spin plots at such a rate. They are apt to become thin or to break…I would not write a Holmes story without a worthy plot and without a problem which interested my own mind, for that is the first requisite before you can interest anyone else.

If I have been able to sustain this character for a long time, and if the public find, as they will find, that the last story is as good as the first, it is entirely due to the fact that I never, or hardly ever, forced a story.”

“I was weary, however, of inventing plots and I set myself now to do some work which would certainly be less remunerative but would be more ambitious from a literary point of view.”

Again, he sounds like a snob. He wrote The Refugees. I don’t know anybody who would prefer that to a Sherlock Holmes story.

Having completed two sets of stories (collected as The Adventures, and The Memoirs), he was feeling trapped by Holmes.

“…I saw that I was in danger of having my hand forced, and of being entirely identified with what I regarded as a lower stratum of literary achievement. Therefore, as a sign of my resolution, I determined to end the life of my hero. The idea was in my mind when I went with my wife for a short holiday in Switzerland…I saw the wonderful falls of Reichenbach, a terrible place, and that, I thought, would make a worthy tomb for poor Sherlock, even if I buried my banking account with him. So there I laid him, fully determined that he should stay there – as indeed for some twenty years.”

The British public collectively lost its mind. Men wore black armbands in mourning. A national hero had died.

“I was amazed at the concern expressed by the public. They sat that a man is never properly appreciated until he is dead, and the general protest against my summary execution of Holmes taught me how many and how numerous were his friends…I heard of many who wept. I fear I Was utterly callous myself.

J.M. BARRIE

There’s a digression, as Doyle talks about a play/light opera that he was commissioned to write with his friend James Barrie, who was as yet a decade away from writing Peter Pan. Jane Annie; or The Good Conduct Prize, ran at the Savoy Theater for a month and-a-half in the summer of 1893. It then ran for a week in Newcastle that same summer. Not exactly a smash hit.

Barrie had contracted to write a libretto for D’Oyly Carte’s light opera. Barrie’s health failed due to a family bereavement. He sent an urgent telegram to Doyle, afraid he couldn’t meet the contractual demands. He had written the first act, and a rough scenario for the second. He asked Doyle to help him complete it.

Doyle wrote the lyrics for the second act, and much of the dialogue. Feeling constrained to work within D’Oyley Carte’s framework, he wasn’t thrilled with the final product:

“The result was not good, and on the first night, I felt inclined, like Charle Lamb, to hiss it from my box. The opera, Jane Annie, was one of the few failures in Barrie’s brilliant career. We were well abused by the critics, but Barrie took it all in the bravest spirit, and I still retain the comic verses of consolation which I received from him the next morning.”

Barrie sent over a copy of his book, A Window in Thrums, to Doyle. He actually wrote a Holmes parody on the flyleaf, as a joint chuckle about their adventure. You can read “The Adventure of the Two Collaborators” at this link.

Doyle said of it:

“This parody, the best of all the numerous parodies, may be taken as an example, not only of the author’s wit, but of his debonair courage, for it was written immediately after our joint failure, which at the moment was a bitter thought for both of us. There is, indeed, nothing more miserable than a theatrical failure, for you feel how many others who have backed you have been affected. It was, I am glad to say, my only experience of it, and I have no doubt that Barrie could say the same.”

I’m not a big Peter Pan guy, so I don’t know much about Barrie. But I really admire the guy for whipping off a parody, putting it on the flyleaf of his own book, and then gifting it to Doyle, while the sting was still fresh. That’s pretty cool.

SIDNEY PAGET

Doyle spends one paragraph on the impersonations of Holmes. He says that they’re all very different from his own original idea:

Doyle spends one paragraph on the impersonations of Holmes. He says that they’re all very different from his own original idea:

“I saw him as very tall (‘Over six feet, but so excessively lean that he seemed considerably taller,’ from A Study in Scarlet). He had, as I imagined him, a thin razorlike face, with a great hawk’s-bill of a nose, and two small eyes, set close together on either side of it. Such was my conception. It changed, however, that poor Arthur Paget, who before his premature death, drew all the original pictures, had a younger brother whose name, I think, was Harold, who served him as a model.”

It’s Elementary – Doyle meant Sidney Paget, not Arthur, as the artist. The brother who modeled Holmes was Walter (there was no Harold). Another brother, Henry, denied that Walter was the model.

“The handsome Harold took the place of the more powerful but uglier Sherlock, and, perhaps from the point of view of my lady readers, it was as well. The stage has followed the type set up by the pictures.”

It’s Elementary – Here’s an essay I wrote on Paget and Holmes.

BUILDING A HOLMES STORY

Next, asked whether he knew the end of a Holmes story before he started it:

“Of course I did. One could not possibly steer a course if one did not know one’s destination.”

He says the first thing is to get the idea (he uses “The Sussex Vampire” as an example here). Then, conceal the key idea and “lay emphasis upon everything which can make for a different explanation” (bit of the red herring concept there). “But Holmes can see all the fallacies of the alternatives and arrives at the solution by steps which he can describe and justify.”

He uses “clever little deductions” which impress the reader. Similar to his allusion to other cases.

“Heaven knows how many titles I have thrown about in a casual way, and how many readers have begged me to satisfy their curiosity about” what we now call Watson’s unchronicled cases.

That was a mini-lesson from Doyle on the putting together of a Holmes story.

QUESTIONS ABOUT CERTAIN STORIES

He next talks about the mistake which readers pointed out to him regarding bicycle tracks in “The Adventure of the Priory School.” Then, how his “ignorance cries aloud to Heaven” in “Silver Blaze.”

A LITTLE KINDNESS ABOUT HOLMES

He then softens his often harsh feelings towards Holmes:

“I do not wish to be ungrateful to Holmes, who has been a good friend to me in many ways. If I have sometimes been inclined to weary of him, it is because his character admits of no light or shade. He is a calculating machine, and anything you add to that simply weakens the effect. Thus, the variety of the stories must depend upon the romance and compact handling of the plots. I would say a word for WAtson also, who in the course of seven volumes never knows one gleam of humor or makes a single joke. To make a real character one must sacrifice everything to consistency and remember Goldsmith’s criticism of Johnson that ‘he would make the little fishes talk like whales.’”

THE SPECKLED BAND ON STAGE

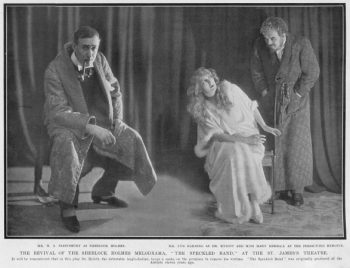

Next are two paragraphs talking about the play for “The Speckled Band.”

It’s Elementary – I wrote an essay with all you could want to know about the play, here. Also, an essay on the Raymond Massey movie, which was based on the play, not the short story.

He recounts that his boxing play based on Rodney Stone was withdrawn, but he had paid for a six month theater lease. He shut himself in and wrote a Holmes play in a week, based on ‘The Speckled Band.’ He referred to it as “a considerable success,” which it was.

He recounts that his boxing play based on Rodney Stone was withdrawn, but he had paid for a six month theater lease. He shut himself in and wrote a Holmes play in a week, based on ‘The Speckled Band.’ He referred to it as “a considerable success,” which it was.

They used a live boa for the play. Doyle never took criticism well, and he voiced his disgust at the critic of the Daily Telegraph, who ended his “disparaging review by the words: ‘The crisis of the play was produced by the appearance of a palpably artificial serpent.’”

Doyle said he often thought of offering the critic “a goodly sum” to go to bed with the snake.

There were multiple snakes used. A stage carpenter would pinch their tails to make them more lively. Sometimes they crawled back through the hole to get even with him. Finally they switched to artificial snakes, which the stage carpenter fully supported!

He briefly mentions that he gets letters sent to Holmes and Watson – sometimes asking them to solve a mystery.

It’s Elementary – The late Richard Lancelyn Green edited a book, Letters to Sherlock Holmes.

WRAP UP

He both seems to encourage and discourage that he is like Holmes, in a paragraph.

And finally he relates that he heard of some French schoolboys, who, when asked the first thing they wanted to see in London, replied that it was Holmes’ lodgings in Baker Street. He then realized what a living, actual personality Holmes had become.

I am going to do a couple more posts on essays actually written by Doyle, related to Holmes. But this one definitely had ‘a lot of meat’ in it. And we get some insights directly from ACD on his famous creation.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE DEFINITIVE guide to Conan. He also organized 2023’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

Doyle was one of the great storytellers in an age of great storytellers.

I happen to be reading The Horror in the Heights and Other Suspense Stories by Doyle at this moment.

Now I’m curious: Years ago I read several essays by Dorothy L. Sayers on Holmesiana, including one that discussed which university he attended and what course he enrolled in there. They were included in a collection titled Unpopular Opinions. By any chance do you have any version of these in your collection, or have you ever run across them?

I know I’ve read Sayers’ essay, but I don’t have the book. I think the only Sayers book I have is her biography of Erle Stanley Gardner.

No Wimsey? Your library has a gaping hole in it. They paint a picture of post WW1 England that is fascinating. And “Murder Must Advertise” puts Mad Men to shame in portraying the advertising industry.

When I think of Holmes, I am reminded that military Holmesiana is almost a sub-genre. Hesketh Vernon Hesketh-Pritchard, who wrote the Flaxman Low psychic detective novels and the Holmes tribute novel ‘November Joe’, famously ran an army sniper school in WWI and managed to find a billet for Doyle’s son as a patrol officer (managing scouts and snipers). Basil Rathbone, who played Sherlock so often on screen, was also a patrol officer.