Fantasia 2021, Part XXII: Baby, Don’t Cry

“Munkie” is a 15-minute short film from New Zealand written and directed by Steven Chow. It follows Rose (Xana Tang), a youth with controlling parents who are immigrants or of recent Asian ancestry. Rose has a plan to stop their interference in her life. But things do have a tendency to go wrong. It’s a fictional story based on a true crime, and it’s very well-done, sketching character and atmosphere coldly and even brutally. It’s a shocking story, and ends in a strong place — that is, a place which leaves the viewer briefly wanting more. In fact it’s a tightly-structured story that does its damage and gets out at the right moment.

“Munkie” is a 15-minute short film from New Zealand written and directed by Steven Chow. It follows Rose (Xana Tang), a youth with controlling parents who are immigrants or of recent Asian ancestry. Rose has a plan to stop their interference in her life. But things do have a tendency to go wrong. It’s a fictional story based on a true crime, and it’s very well-done, sketching character and atmosphere coldly and even brutally. It’s a shocking story, and ends in a strong place — that is, a place which leaves the viewer briefly wanting more. In fact it’s a tightly-structured story that does its damage and gets out at the right moment.

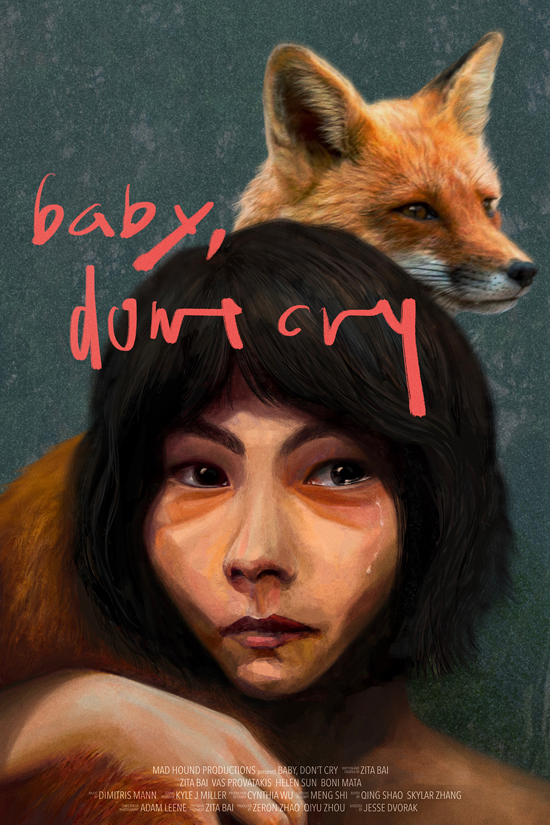

Bundled with that short was Baby, Don’t Cry, an American movie directed by Jesse Dvorak. But the main creative force behind the movie seems to be screenwriter and star Zita Bai, who plays Baby, a teenage daughter of Chinese immigrants to the northwestern United States. An outcast, Baby’s got an almost overwhelming interest in filming what is around her, perhaps less as a way to make films and tells stories than to document and record her life. And then she falls in with Fox (Vas Provatakis), a tall shaven-headed white punk leading a wild but independent life. Flashbacks and moments of surrealism and things seen through the camera lens are integrated well, as Baby finds herself pulled from her parents’ abusive home toward an uncertain adulthood.

It’s a movie that hangs out on the edge of genre. You’re never really sure if it’s about to turn into a full-fledged crime story, and I suppose it doesn’t quite, but the very end of the film suggests it should be read as an unconventional fantasy. Or, indeed, on the edge of fantasy and myth. You could perhaps read it as a mimetic story, but I think that would run counter to the plain meaning of what we see (and a question-and-answer session with the filmmakers, available on Fantasia’s YouTube page, would seem to confirm this). It’s an ending that to me opens up a number of further questions, inviting a second watch to see what plays out differently and what does not have the meaning we thought. And this is no bad thing.

There is a sense of violence always near in this story, a sense that grows stronger as Baby moves more and more deeply into Fox’s life. It’s an existence on the extreme margin of society, though we’re given to understand Fox and his sister Sky (Boni Mata) come from money. Whatever their background, they live a life now marked by theft, fistfights, and drugs. What is interesting, and lifelike, is that the sense of incipient physical danger doesn’t come from one single clear source, doesn’t have an arc with foreshadowing and setups and payoffs, and doesn’t feel like a standard element of narrative tension. It’s a state of life. Fox and Sky and (as the film goes on) Baby live in a world where there are fights and shady deals after midnight and so on and so forth, and there are guns and knives, and that’s how it is, and you only hope these things don’t come together the wrong way.

All of which is to say that this is a character-driven movie, built not out of a tight plot with conventional twists and resolutions but out of the people we see and the way they bounce off of each other. More precisely, it’s about Baby and how she’s shaped by her environment and what she makes out of what’s around her. The film’s sparing with dialogue but stunningly well-acted. Out of a talented cast special mention has to go to Provatakis, who builds a convincing cold-eyed punk who also has moments of youth and even a kind of innocence. (Comparing Provatakis’s affect in the film against his affect in the online Q&A is a primer on how much a good actor can build a character with a stance and expressions and mannerisms completely different from who they usually are.)

All of which is to say that this is a character-driven movie, built not out of a tight plot with conventional twists and resolutions but out of the people we see and the way they bounce off of each other. More precisely, it’s about Baby and how she’s shaped by her environment and what she makes out of what’s around her. The film’s sparing with dialogue but stunningly well-acted. Out of a talented cast special mention has to go to Provatakis, who builds a convincing cold-eyed punk who also has moments of youth and even a kind of innocence. (Comparing Provatakis’s affect in the film against his affect in the online Q&A is a primer on how much a good actor can build a character with a stance and expressions and mannerisms completely different from who they usually are.)

It may be worth noting that Baby and Fox have a bluntly sexual relationship, which feels honest for the age of the characters. Again, it’s played well, with a lot of reverses and fights in and among the sex and moments of romance. Fox gives Baby a chance to explore her own physicality, not only in sexual terms but also in pushing her capacity for violence.

There is an odd reversal here: Baby’s from a home of not-too-well-off immigrants, and her mother suffers severe mental issues. But the white kids live a more hardscrabble life, though they’ve supposedly come from money. The end of the movie makes us wonder what to believe, exactly, but the point is that Baby begins the film as a relative innocent and it is through Fox that she learns to let out her aggression and anger. She grows wilder and more assertive.

There is an odd reversal here: Baby’s from a home of not-too-well-off immigrants, and her mother suffers severe mental issues. But the white kids live a more hardscrabble life, though they’ve supposedly come from money. The end of the movie makes us wonder what to believe, exactly, but the point is that Baby begins the film as a relative innocent and it is through Fox that she learns to let out her aggression and anger. She grows wilder and more assertive.

She also keeps filming everything she sees around her. This is a story about the coming of age of a filmmaker, therefore a kunstlerroman, a portrait of the artist as a young woman. And you can see, I think, how Baby’s life affects what she chooses to film; how racial slurs thrown at her, and issues at home, and her relationship with Fox are all seen through her lens.

There is relatively little sign in the movie of Baby having an interest in the history of cinema, or of any film culture. She’s something of an outsider artist, then, not influenced by the past except insofar as she lives in a world where she’s exposed to TV shows and cartoons and all the incidental film elements of modern life. (I note in passing that she has little interest in the internet or social media or YouTube, either.) This perhaps emphasises her youth, the sense of something unformed about her; she is drawn to create in a medium without having a historical perspective on it, drawn to a way to represent what she sees without worrying about whether somebody else has already seen or shown the same thing.

There is relatively little sign in the movie of Baby having an interest in the history of cinema, or of any film culture. She’s something of an outsider artist, then, not influenced by the past except insofar as she lives in a world where she’s exposed to TV shows and cartoons and all the incidental film elements of modern life. (I note in passing that she has little interest in the internet or social media or YouTube, either.) This perhaps emphasises her youth, the sense of something unformed about her; she is drawn to create in a medium without having a historical perspective on it, drawn to a way to represent what she sees without worrying about whether somebody else has already seen or shown the same thing.

Baby, Don’t Cry is in some ways a difficult movie to get one’s head around, and the twist at the end explains some things while complicating others. There isn’t much exposition in the dialogue; one must pay attention. There are elements of surrealism that come from Baby’s unreliable perspective on events; it is certainly possible that what I take to be fantastic at the end, paying off a recurring image in the movie, is meant to be Baby’s perspective (although the key moment I am thinking of has her looking away from what is most surreal). But if it is not immediately clear, the film’s an interesting thing to consider and to pick apart. It is unpredictable and unconventional, with characters and a story that have an uncomfortable sense of meaning to them. Perhaps then it’s best to say that in its lacunae and oddity and silences and lack of explanations this is uncomfortable art, in the best sense, with a power not easy to define.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.