Corum and Me: The Redemption of the Scarlet Robes

|

|

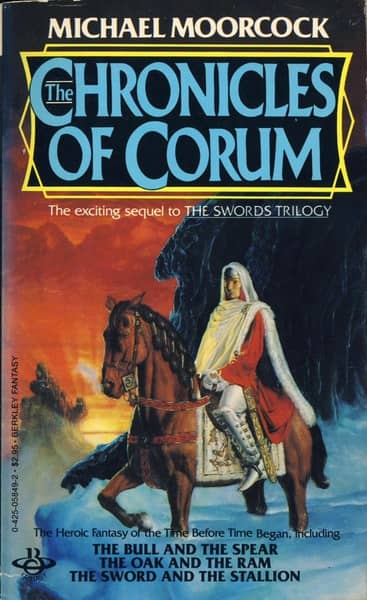

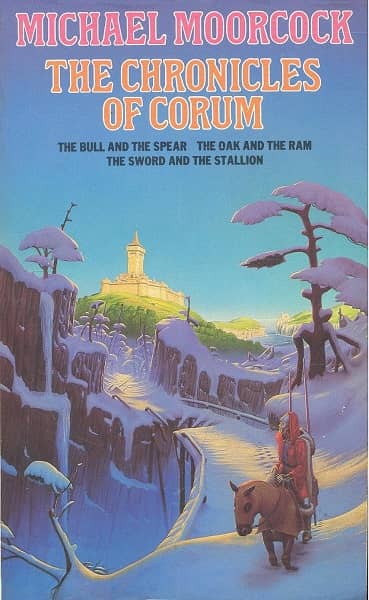

The Chronicles of Corum, Berkley Medallion (1983, artist uncredited) and Grafton (1987, Mark Salwowski)

In late 2017 I published an article at Black Gate called Elric and Me, in which I discussed revisiting Michael Moorcock’s most famous creation. Three years later, I’ve decided to revisit another of his creations, Corum Jhaelen Irsei, the Prince of the Scarlet Robe. Recently I published the first half of the essay, Corum and Me: The Disappointment of the Swords, which discussed my reaction to the first trilogy of Corum novels, frequently called The Swords Trilogy and comprised of The Knight of the Swords, The Queen of the Swords, and The King of the Swords. I came away from the trilogy disappointed and not looking forward to the follow-up trilogy, for my fond memories of Corum were rooted in the first trilogy. (Greg Mele presented a thoughtful counter argument here, in In Defense of Corum, Elric’s Brother-from-a-Vadhagh-Mother.)

The second trilogy, The Chronicles of Corum, including the novels The Bull and the Spear, The Oak and the Ram, and The Sword and the Stallion, is set centuries after the first. It opens several decades after The King of the Swords. Corum’s love, the Margravine Rhalina, has died and he is living an empty existence, occasionally kept company by his companion Jhary-a-Conal.

Suffering from dreams in which people are calling him, he discusses the situation with Jhary-a-Conal, who has a greater than typical understanding of the way the multiverse works. Jhary-a-Conal explains that Corum is being summoned by Rhalina’s distant descendants who are in need of a hero. Their calls are getting weaker as Corum continues to ignore them but if he chooses to go to their aid, it is not too late. Being a hero and an aspect of the Champion Eternal, Corum allows himself to be dragged into his future.

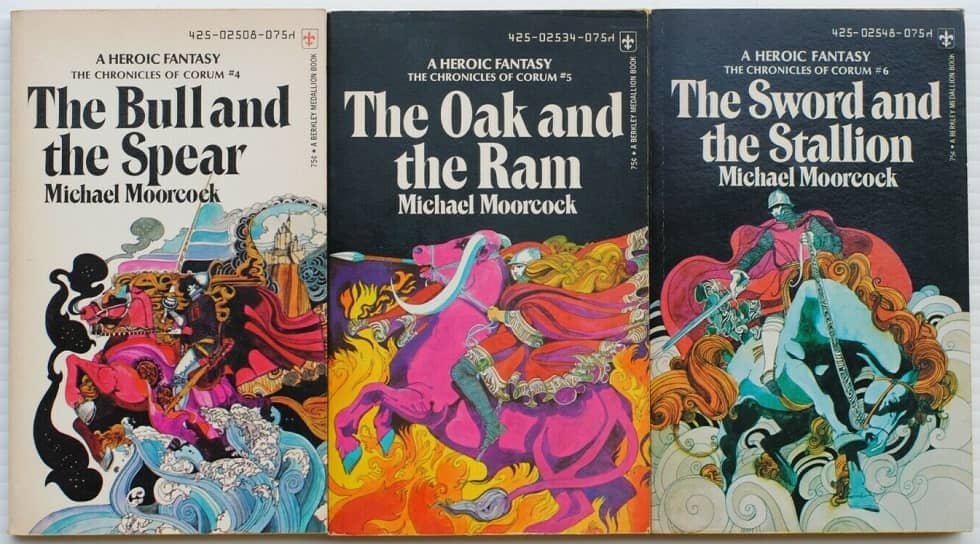

First edition Berkley paperbacks: The Bull and the Spear (1973), The Oak and the Ram (1973),

and The Sword and the Stallion (1974). Covers by David McCall Johnston.

Although there were strong Celtic influences on the first trilogy, they were subtle compared to the inspiration of Celtic mythology in the second trilogy. The Mabden who have summoned Corum are facing an existential threat from extraplanar giants who, although few in number, have armies of servants and minions who can be used to destroy the Mabden. Other races have also shown up in the world since Corum jumped forward in time and offer potential allies and enemies, making Corum’s world almost seem like the way station for the multiverse’s flotsam.

Relationships in this world also seem somewhat unearned, even moreso than in The Swords Trilogy. Corum falls in love with the Mabden princess Medhbh mostly, it seems, because she is there. His strongest relationships are with his longtime companion, Jhary-a-Conal, who happens to drop in on his realm at the appropriate time, and his enemy Gaynor the Damned, now allied with the giant Fhoi Myore.

However, upon re-reading the two Corum trilogies, I find a preference for the second one. While the first trilogy was made up of three very distinct novels, although they are linked by plot, the second trilogy is clearly plotted to be read as a unit. Themes carry through all three novels and minor events in the first novel, The Bull and the Spear, can only be seen for their full import in the final volume, The Sword and the Stallion. This continuity means that while I discussed the individual novels in he first article, here I’ll be discussing the trilogy as a whole.

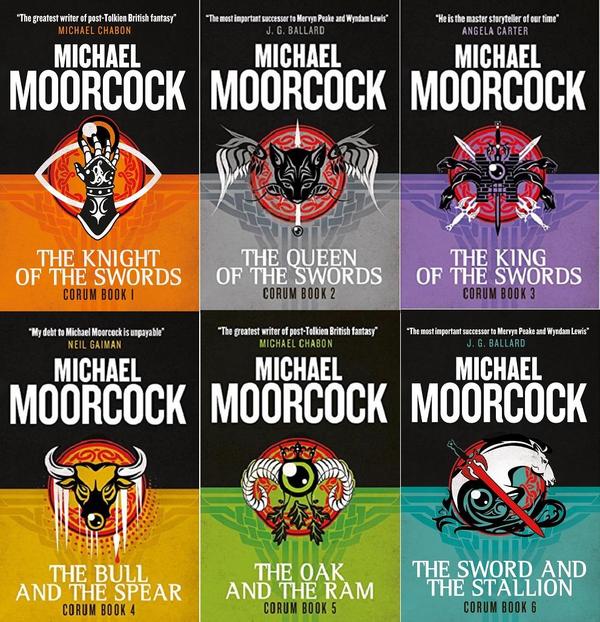

2015 Titan re-issues

One of the themes, which stretches back into the original trilogy but is stronger here, is the question of what creates a deity and where their power comes from. In The Swords Trilogy, Arioch, Xiombarg, and Mabelode are all presented as powerful Lords of Chaos while Arkyn is offered as an example of a Lord of Law. All are nothing when compared to the gods Kwll and Rhynn, the Lost Gods. And all of those gods are ages in the past in the new series. Here, the gods are the Fhoi Myore invaders and Corum, whose deification came about due to the needs of the Mabden who summoned him. The role of gods takes on a more imminent position in the trilogy.

Related to the gods who walk the earth are the places of power that feature throughout the novels. They can serve as magnets for the gods and magic or places that are taboo for the gods to approach. They are also evocative, as intriguing as any of the places visited by Elric or Hawkmoon or Erekosë, partially because Moorcock doesn’t attempt to explain the exact nature of these points of power, how or why they affect the various gods in different ways.

The Corum novels are also extremely important in coalescing Moorcock’s conception of the Multiverse. From the beginning of The Sword Trilogy, the Vadhagh are aware of fifteen planes of existence and have traditionally been able to see and move through five, although that ability is curtailed by the start of the novel. In those books, Corum gains the ability to move through them and meets other aspects of the Eternal Champion, but more importantly, he meets Jhary-a-Conal. This companion, like Erekosë, has memories of his various incarnations and shares those with Corum, giving the hero a level of awareness that Elric and Hawkmoon never had. Similarly, the appearance of so many extraplanar creatures throughout this second trilogy, and their acceptance as such by Corum and Mabden alike, normalizes the idea for both the inhabitants of Corum’s world and the reader who is merely visiting it.

Re-reading the six Corum novels was enlightening, with the three I remembered most fondly seeming lightweight, derivative, and hurried and the novels I remembered less well holding more appeal with a tighter overall plot, more depth in their portrayal of gods, and a more interesting landscape. The first trilogy seemed to offer a promise that it wasn’t able to fully deliver, while the latter trilogy was finally able to live up to the promise, even if Corum did not have two of his distinguishing features (the hand of Kwll and the eye of Rhynn).

Steven H Silver is a seventeen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology, Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings, was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 6 times, as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a seventeen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology, Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings, was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 6 times, as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

I’d agree, Steve. I think maybe Moorcock approached the two trilogies in very different ways. Any time the first series started to flag, he’d introduce something new into the mix – e.g. a castle made out of blood – helped by how the series had the character travelling across different planes of reality. The second series has a couple of key concepts – the cold, the Fhoi Myore – and builds from there.

And sure, I’m probably biased (as I’ve said before, the second trilogy was my introduction to the Eternal Champion) but I actually think it was a good place to start. I read the Elric books last, so inevitably they seemed a bit thin in comparison to subsequent books, as did the character – although I can appreciate how innovative they were at the time.

I particularly remember the cover for ‘The Oak & the Ram’- which was by Patrick Woodroffe (so my copy was the ’74 UK edition) –

https://www.sci-fi-o-rama.com/2009/12/29/patrick-woodroffe-the-oak-the-ram/

Thanks for that Woodroffe cover Aonghus. I don’t think I have seen it before. Loved his art in The Pentateuch of the Cosmology.

Pretty cool, huh? I actually think it’s the best of the three.

The Corum series was very influential on my thinking and aesthetic on my earlier writing. I love the cosmic weirdness of Moorcock and still do. Great post!

Well, damnit, Steven, I can’t go and write a rebuttal article, because now I have to go and reread the books first! Although I read the first trilogy thrice, I only ever read these once, and disliked the ending so much that was that. I suppose, from the vantage of three decades later, I should take another look.

Have read and re-read the Corum and Elric books over the years. Always preferred Corum. Recently re-read both Corum trilogies and enjoyed them yet again. Do they compare to the works of Sapkowski and Abercrombie, the two modern masters of Sword and Sorcery? No, they do not. And they pale in comparison to the all time great novel that clearly influenced Moorcock so, Anderson’s The Broken Sword. But I always found Corum a likable, tragic hero (much more so than Elric). I loved the Hand of Kwll and Eye of Rhynn dynamic and found myself pulling for Corum to defeat Glandythe and avenge his crippling. Agree that the Chronicles are the superior books. I found them very engrossing, but I love Celtic Mythos. The Chronicles are at their best convincingly haunting – I loved the ending and found it borderline scary (Corum defeated by a younger, stronger, tireless doppelganger and seemingly betrayed by his woman). I actually found the Corum – Medhbh romance very convincing (what woman wouldn’t be attracted to a handsome Elfin demi-God summoned to save her people)? Loved the notion of the giant Sidhe too, Ilbrec in particular.

I consider the six Corum books S&S Classics. Part of my love of them undoubtedly is due to the memories of my youth they evoke, exploring the Fantasy Sections of the local bookstore and picking books based on the quality of the cover illustrations, hoping the story inside matched the art. Corum did not disappoint.