Elric and Me

|

|

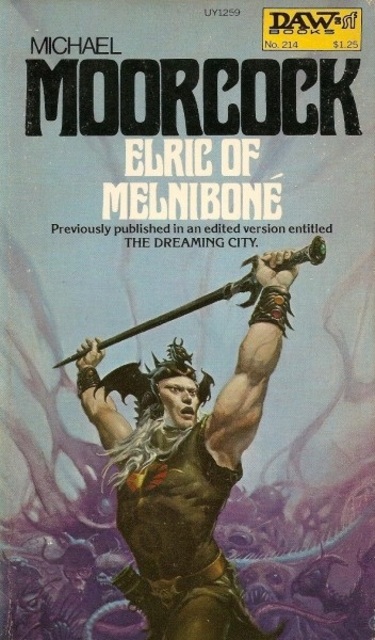

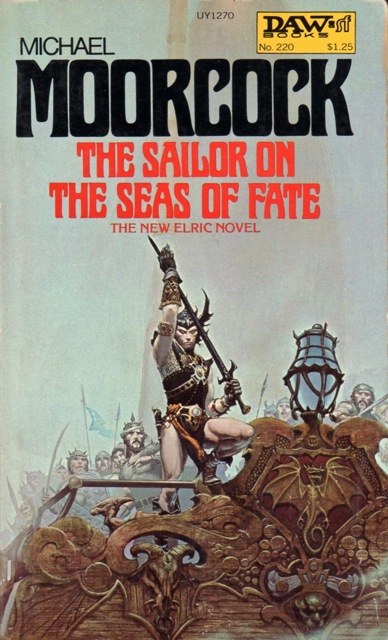

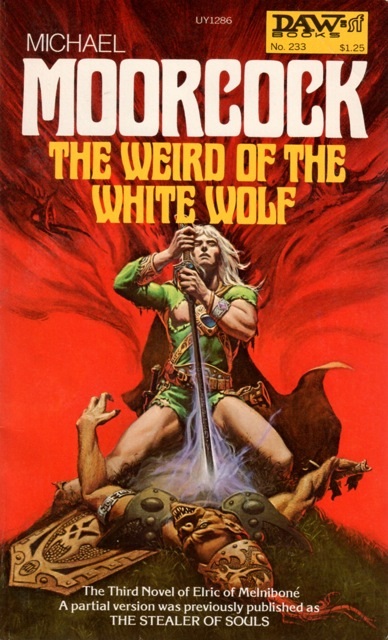

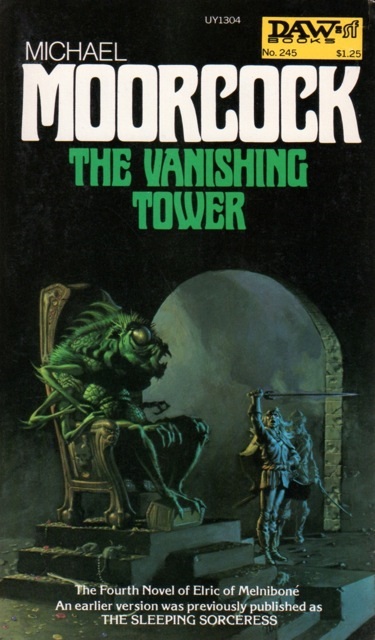

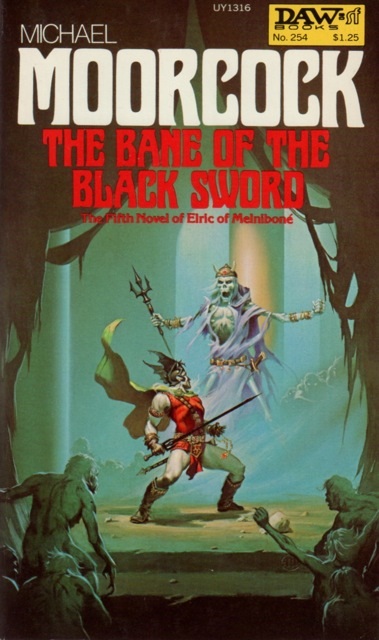

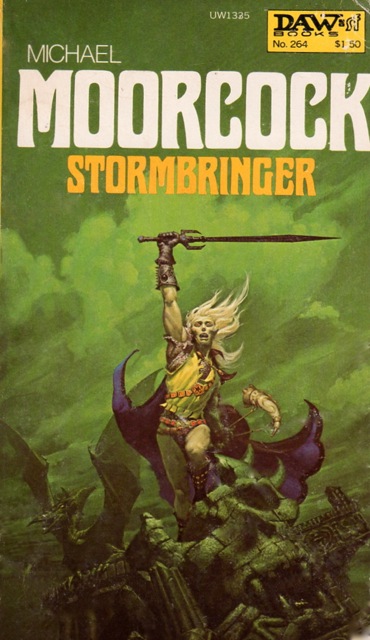

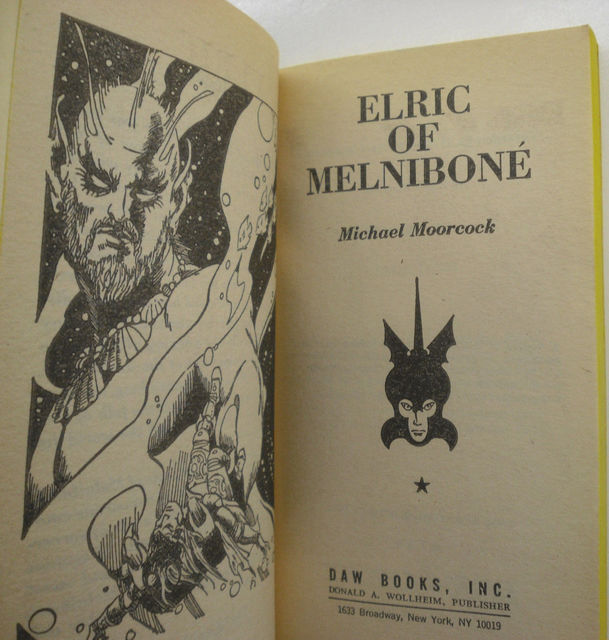

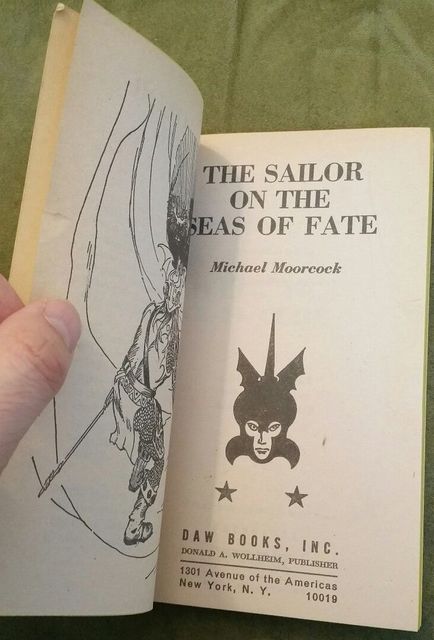

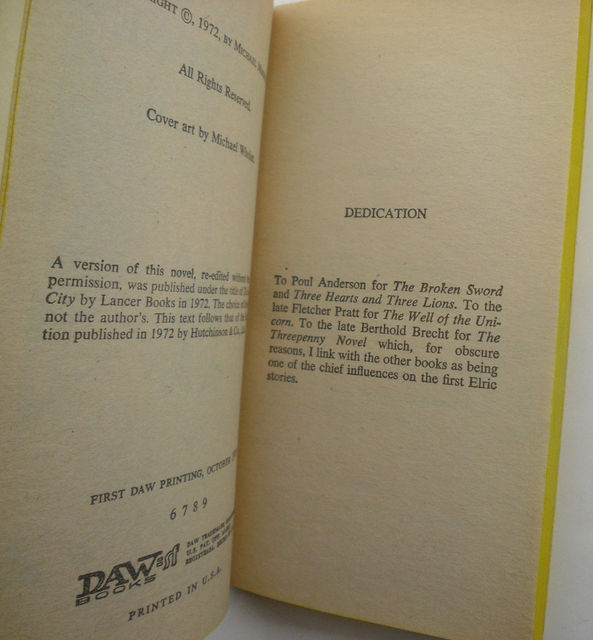

My introduction to Michael Moorcock’s Elric came from a single line in the Advanced Dungeons and Dragons Dungeon Master Guide. Gary Gygax included a note in Appendix N that Michael Moorcock’s Stormbringer and Stealer of Souls, as well as the first three books of the Hawkmoon series, influenced the game. I sought out the Elric cycle (as well as the Hawkmoon, Corum, Erekosë, etc.) in the DAW editions with cover art by Michael Whelan.

It was a great time to discover the books, since they were all in print and relatively easy to obtain. I worked my way through as many of Moorcock’s books as I could find, including his Dancers at the End of Time series, Michael Kane/Warrior of Mars series, and even books like The Black Corridor, The Wrecks of Time, and The Shores of Limbo. I remember my elation upon finding a used copy of The Ice Schooner in a used bookstore in New Haven, CT after searching for it through several states in those pre-internet days.

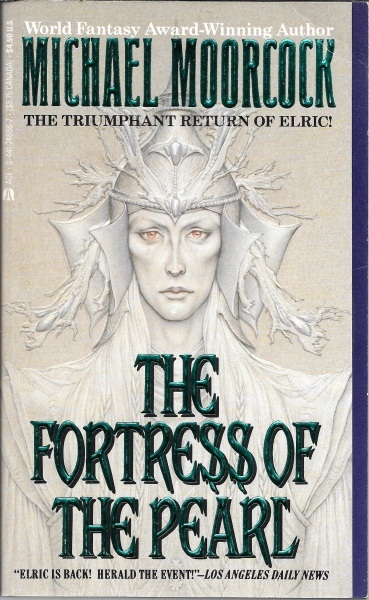

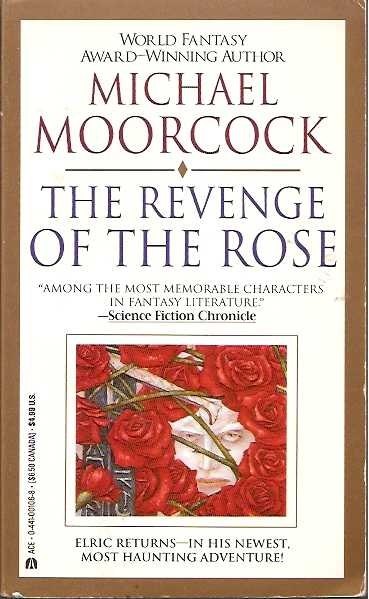

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

|

|

Over the years, I replaced many of those yellow-spined DAW books (as well as editions purchased from England, like my copy of Moorcock’s Book of Martyrs). In the 1990s, when I was working in a bookstore, I replaced most of them with the fifteen volume omnibus editions published by White Wolf.

Although in recent years, I’ve read many of Moorcock’s books when they were first published, including the Oona von Bek series related to Elric, and had re-read his Michael Kane series in 1998 and The History of the Runestaff in 2010, it has been quite a long time since I picked up Elric of Melniboné and read the books that made up that cycle, or the books I considered “new” since they were published after I had discovered Elric.

|

|

A couple months ago, I was in the mood for some good old-fashioned Sword and Sorcery. I flip-flopped between re-reading Moorcock’s Elric series and Fritz Leiber’s Lankhmar series. Although I initially picked up Swords and Deviltry and began reading “The Snow Women,” I soon found myself reading Elric of Melniboné. Nine books later and I had read my way through the end of Elric’s world in Stormbringer as well as what may be describes as Elric apocrypha, the stories “Elric at the End of Time,” which combines Elric and the Dancers at the End of Time, and “The Last Enchantment,” which were included in the collection Elric at the End of Time but are not considered canonical Elric stories.

As I read through the stories, I realized that they were more vivid in my memory than they were on the page. The importance of events in the books also changed the way I remembered them. Major characters, or characters I thought were major, had very small roles and vice versa. I realized that for all the shadow they threw on Elric’s history, his cousins Cymoril and Yyrkoon actually appear in very few stories and are only mentioned in a few more.

The major villain of the epic, Theleb K’Aarna, appears in numerous stories, but he is mostly ineffectual, his vendetta against Elric spurred on by Theleb K’Aarna being spurned by his lover, Yishana of Jharkor, who was quickly overthrown by Elric, while Elric wanted to rid himself of Theleb K’Aarna not because of any epic theme, but simply because the Pan Tangian wizard was a pain in Elric’s ass. Jagreen Lern only appears in the final book and is one of the few villains who can hold his own against Elric, while the other major character introduced in Stormbringer, Sepiriz, is barely more than a deus ex machina in a series filled with gods.

|

|

The novels (and collected short stories) often give the feeling that they are mere outlines for a more complex work. The books comprising the original Elric cycle were only about 200 pages each, anemic compared to modern day fantasy novels that are easily two to three times as long. The brevity of the stories is most clear in Moorcock’s battle sequences, which often seem to consist of Elric rushing in with Stormbringer drawn, shouting a few choruses of “Blood and Souls for My Lord Arioch,” and finding himself suddenly surrounded by dead enemies (and occasionally a soul-sucked ally). These sequences leave the reader wanting more. Stormbringer also isn’t quite as deadly to Elric’s companions as memory made it out to be, although that changes in the final volume.

Scenes that Moorcock was fine writing in the 1960s do not feel particularly detailed or fleshed out fifty years later. Readers who are accustomed to 500 page fantasy novels are going to feel like there is something missing from a 175 page novel, even if it otherwise engages their sense of wonder.

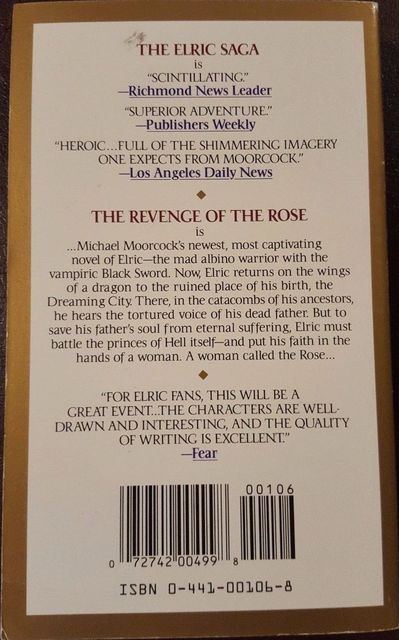

There are very good reasons for the changes. Moorcock was mostly writing short stories, which limited what he could do. The technology of the period also meant that books tended to be shorter, so even when Moorcock was writing for the novel market rather than the magazine market, he was limited to 200 pages. That said, the later novels in the series, Fortress of the Pearl and The Revenge of the Rose, which do not suffer from the issues of the earlier works as much, are among my least favorite of the Elric novels.

|

|

|

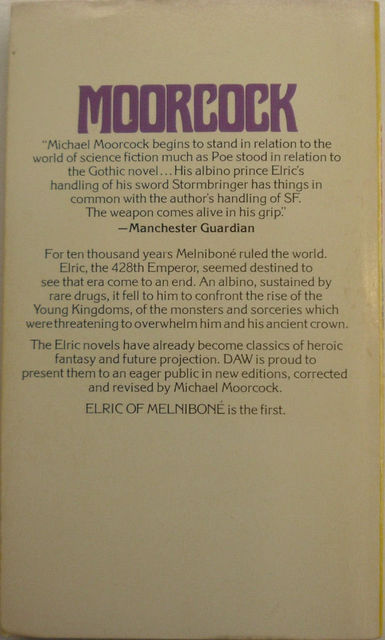

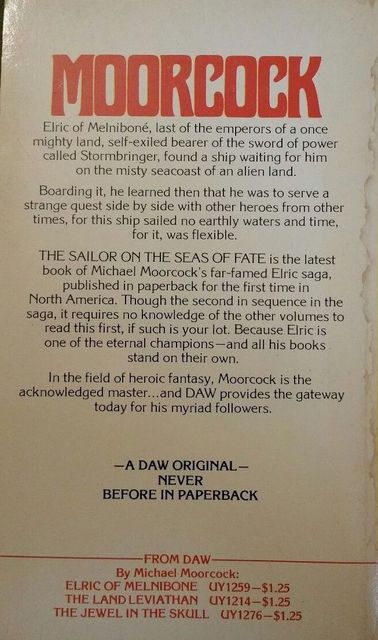

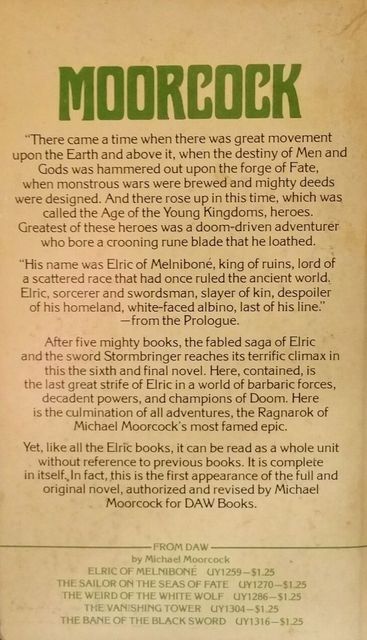

Back covers for Elric of Melnibone, The Sailor on the Seas of Fate, and Stormbringer

Although Elric travels across the Young Kingdoms, hitting many of the places Moorcock has named on the maps, he spends very little time in any one place and has numerous adventures in other worlds. Both of the later Elric novels, The Fortress of the Pearl and The Revenge of the Rose pretty much leave the Young Kingdoms behind, and portions of Elric of Melniboné, Sailor on the Seas of Fate, and The Vanishing Tower all take place in the worlds beyond Elric’s native plane. This extra planar travel seems more integrated with Elric’s main saga in the older works, with the newer novels (granted they were published in 1989 and 1991) seeming to be completely separate from the series’ internal chronology.

The majority of the stories in the Elric saga were written in the early 1960s by a young man in his early twenties, writing before the sexual revolution hit its stride. Women, when they appeared in the saga, were essentially sexual playthings for Elric, no matter how much Moorcock tried to depict Yishana or Lady Myshella or Cymoril or Zarazonia as powerful women. Elric’s, and Moorcock’s, treatment of these characters is cringe-worthy. By the time Moorcock introduced Oone in The Fortress of the Pearl or the title character in The Revenge of the Rose, he has clearly learned how to write powerful female characters who can relate to Elric as an equal, and, as with Rose, his superior.

|

|

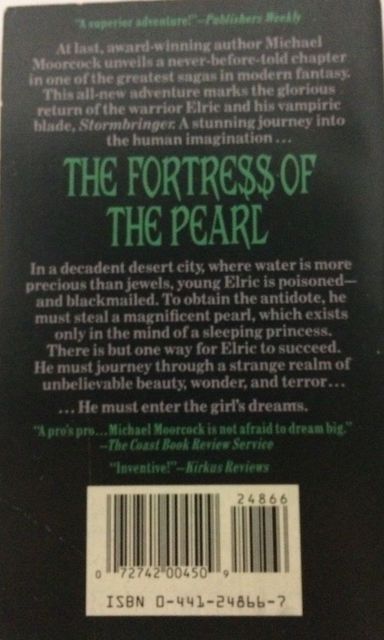

Back covers for The Fortress of the Pearl and The Revenge of the Rose

However, there are, of course, aspects of Elric which succeed. Moorcock’s ability to create new and unique places for Elric and his companions to venture remains intact. Although Moorcock often describes these places, from the dreaming towers of Imrryr to the pulsing cavern where Elric and Yyrkoon obtained their hellblades, in only a few words, they come to life with vivid imagery.

Moorcock’s ability with nomenclature is also magical throughout the books. Although Moorcock has stated that he had no philosophy regarding the names of his characters, creatures, and places, they are consistently evocative in presenting an otherworldly feel for his saga, whether the decrepit city of Quarzhasaat, which believes it vanquished the Melnibonéan empire, Terarn Gashtek, the barbarian king ready to ride roughshod over the Young Kingdoms, or Haaashaastaak, the lord of lizards.

|

|

Dedication for Elric of Melnibone

Of course, for whatever weaknesses the Elric saga currently exhibits, Moorcock’s influence, in these books and others, can clearly be seen in modern epic fantasy either directly or through the influence he had on Gygax when the ideas of alignment were introduced into role playing games.

See our previous coverage of Michael Moorcock’s fiction at Black Gate here.

Steven H Silver is a fifteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW and NESFA Press. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Big White Men—Attack!” in Little Green Men—Attack! Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 5 times as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7. He has been the news editor for SF Site since 2002.

Great post! Nostalgia! My introduction to Elric was also through AD&D but the Deities and Demigods manual. The artwork and ideas in that book intrigued me and I tracked down my copies through Waldenbooks. If I remember rightly, my aunt ordered the rest for me (again through Waldenbooks). Oh the old days before the internet!

The versions I had were the Berkeley paperbacks; but I later tracked down the DAW editions as well (both are on my shelf right now). I also have the big Del Rey editions that came out a few years ago and I have some newer UK editions too.

I love returning to these books, as well as many of Moorcock’s other early creations, in the Eternal Champion universe. Because they’re shorter, they tend to have a more punchy, down-n-dirty feel to them. I love Moorcock’s blending of swords and magic and gods and demons and and proto-sci-fi stuff. Though to my mind (and probably still to Moorcock’s chagrin) classic fantasy (like Tolkien) strikes me as richer form of literature than this S&S. But I love S&S! In the same way the Beethoven is probably better than The Police, I still love The Police!

I think I also first encountered Moorcock through Deities & Demigods; and I still have a major soft spot for the original Elric/Hawkmoon/Corum/Eternal Champion stuff. Some of which I probably need to revisit soon.

I always loved the fact that he had such a vast & sprawling multiverse with visits to different planes &c. That’s one complaint I have with a lot of modern fantasy — even though the books are much bigger, the locations are much more constrained.

I track back a bit further with Elric, first to the Lancer unauthorized edition of The Dreaming City (under their Magnum imprint). Then, when the DAW editions came out, I was spurred on by the OD&D supplement Gods, Demi-Gods, and Heroes, if I needed any further encouragement. But, as Joe H. points out, Moorcock’s febrile imagination was enough enticement to draw me back, again and again.

Outline is a good way to describe my impression of reading Elric. The idea of a story is good, but the presentation very lightweight. I want to like Elric more than I do.

@Kallies

I’m not sure you’re supposed to like Elric. I think he pretty much fits the standard definition of an antihero. The old Deities and Demigods manual actually listed his alignment as chaotic evil—boy is that a nerd fact to know!

I get your point about “lightweight” though. I think the pulpiness of the Elric tales is fairly apparent. Once in awhile there’s a tale that goes a little deeper, like “While the Gods Laugh” where he seeks out the artifact known as The Dead Gods’ Book, which is supposed to contain all the answers to the deepest questions of mankind. When Elric eventually finds it the book has actually deteriorated to crumbling dust. I think Moorcock is making some sort of deeper comment here.

Just rereading Bane of the Black Sword. Despite some of it being written hurriedly and rather clumsily, the best of Elric is up there as the best sword and sorcery ever written. If Vance, Leiber and Howard are the Sword and Sorcery Trinity (and C.L. Moore the Holy Virgin), Moorcock is their only begotten Son. An incredible achievement, a great inspiration for me, and a wonderful memory to return to every few years. And those Whelan covers!

I would slightly disagree with you about female characters being weak when it comes to Yishana, however.

Thanks for the trip down memory lane, Steven!