Breaking News: HBO’s The Plot Against America Parts 4-6

The story so far: in this tale of an alternate America, based on a pseudo-memoir written by Philip Roth, anti-Semite Charles Lindbergh was elected president in 1940, keeping the USA out of the war in its darkest hours and inaugurating a scary time for American Jews, especially 9-year-old Philip Levin (Azhy Robertson).

Feelings about the Lindbergh administration vary through America’s Jewish community. For some, like Rabbi Bengelsdorf (John Tuturro) and his new bride Evelyn (Winona Ryder), it’s an opportunity for social climbing and collaboration. To some, like young Sandy Levin (Caleb Malis), Lindbergh is a hero and any concerns to the contrary come from ignorant frightened “ghetto Jews” — like his parents. For some, like Philip’s overbearing Uncle Monty (David Krumholz), business is good; the nation is at peace; there are worse things than President Lindbergh.

Others (young Philip’s parents, played by Morgan Spector and Zoe Kazan, and his cousin Alvin, played by Anthony Boyle) are intent on resisting the tide of anti-Semitism rising in America and the rest of the world. But, tragically, they can’t agree on what should be done and end up fighting with each other as much or more than with the real enemy.

(That’s the sitch in episodes 1, 2, and 3, which I earlier discussed here, here, and here. A note that might be useful in making sense of what follows: in Roth’s novel, the Jewish family at the center of the story is named Roth. In the HBO series, the family’s name is changed to Levin, possibly to avoid slandering some of the real people on whom Roth based his characters.)

Anyway: now the entire show has been broadcast and you can binge it at your leisure. (If you can afford HBO I assume you have some leisure.)

Apologies for letting these installments fall through the cracks in my April. If you’ve ever had cracks in your April, you know just how painful it can be.

Was I busy? I guess! But — since it’s just you and me here, I might as well admit it — the truth is that I was dismayed by the prospect of saying, each week, “Well, there were good moments and bad moments, but overall…”

So, instead, here I am, after the series is concluded, to say: Well, there were good moments and bad moments, but overall…

Overall: there was a character missing.

Who am I talking about? Kurt Vonnegut knows.

Kurt Vonnegut and Person or Persons Unknown

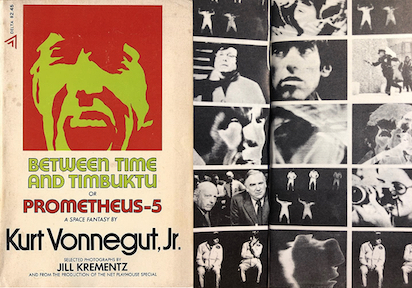

I secretly and pointlessly love a TV movie that practically nobody else knows about and is possibly not very good. It’s called Between Time & Timbuktu.

The book of the movie, because there’s no movie of the movie

It was broadcast on NET, the predecessor of PBS (that’s how old it is), and it’s a free adaptation of a bunch of things by Kurt Vonnegut — short stories (“Harrison Bergeron”, “Welcome to the Monkey House,” etc), novels (The Sirens of Titan, Cat’s Cradle, etc) and a play (Happy Birthday, Wanda June). They all got tossed into a blender, mixed together with some brilliant character actors (William Hickey, comedy giants Bob Elliot & Ray Goulding, Dortha Duckworth, Kevin McCarthy), and poured into two hours of educational television. It’s super-weird. (It’s never been on disc or even VHS; you might be able to find it on YouTube or the equivalent.)

The script was published as a book by Vonnegut, who provided a preface to say, yes he did write it, and also he did not. He goes on to say how much he loves it and, by implication, how much he hates it.

If you’re wondering what the point of all this was, I have finally arrived there.

Vonnegut writes in his preface,

In a movie, somehow, the author always vanishes. Everything of mine which has been filmed so far has been one character short, and the character is me.

I don’t mean that I am a glorious character. I simply mean that, for better or worse, I have always rigged my stories to include myself, and I can’t stop now. And I do this so slyly, as do most novelists, that the author can’t be put on film.

Every deeply felt novel which has been turned into a movie has, as a movie, seemed one character short to me. It has made me uneasy on that account. I suspect that the audience has been vaguely uneasy, too — for the same reason.

What we’re talking about is the narrative persona. The narrator is never the same as any character in the story, even if they go by the same name. (The narrator knows stuff that none of the characters do, for instance.) But the narrative persona can ascend to the level of a character. This is, I think, what Vonnegut is talking about when he refers to a novel as “deeply felt.”

Roth’s novel The Plot Against America is deeply felt in this way. A lot of its power comes from the ironic tension between the point-of-view character (Philip Roth at 9) and the narrator (Philip Roth at 70 or so). There are ways to restrict the POV of a movie or TV show to that of a child (e.g. The Red Balloon, or A Christmas Story), but there’s the danger of losing a certain seriousness. (See some criticisms of Roberto Benigni’s Life Is Beautiful, for example.) The makers of the HBO The Plot Against America chose to go another way: open up the story so that it becomes a drama of many voices. The result is a picture that’s broader than the one drawn by the book, but also flatter, less personal.

It’s also, I have to say, emptier than the book — often less dramatic.

One example. In the show, as in the book, cousin Alvin returns from the war missing a leg. He’s put into the same bedroom as young Philip and the 9-year old (through a combination of guilt and morbid fascination) learns to carefully tend his cousin’s stump. We know about this in the book because we see it through young Philip’s horrified eyes, the events annotated by cynically compassionate commentary in old Philip’s voice. In the TV show we know about these events because Alvin tells one of his friends about them. Television is a medium made for the show-don’t-tell principle, but the scenarists on several occasions preferred to tell rather than show. It’s weird and mutes the emotional impact.

Some things they don’t even tell. The duplex where the Roths and the Wishnows live has a basement that, in the novel, assumes a dark importance, haunted (in young Philip’s eyes) with the ghosts of his dead relatives and the late Mr. Wishnow. One day young Philip comes home to find Alvin missing and searches the house for him, only to find him in the haunted basement.

I heard faint moaning sounds rising from below—ghosts, the suffering ghosts of Alvin’s mother and father! When I edged down the cellar stairs to see if they could be seen there as well as heard, what I saw instead, up by the front wall of the cellar, was Alvin himself peering out of the horizontal little glass slit that looked at street level onto Summit Avenue. He was in his bathrobe, a hand to help him maintain his balance clutching the narrow sill. The other hand I couldn’t see. He was using it for something that I was too young to know anything about.

There were some young women in the alleyway and Alvin was releasing a hydraulic pressure that pre-pubescent Philip doesn’t understand. Philip sneaks away and only returns later to figure out what Alvin was looking at.

I dared to descend the stairs, dashing quickly past the wringer and around the drains, and once at the window and up on my toes — intending only to look out at the street the way he did — I discovered the whitewashed wall beneath the window slick and syrupy with an abundance of goo. Since I didn’t know what masturbation was, I of course didn’t know what ejaculate was. I thought it was pus. I thought it was phlegm. I didn’t know what to think, except that it was something terrible. In the presence of a species of discharge as yet mysterious to me, I imagined it was something that festered in a man’s body and then came spurting from his mouth when he was completely consumed by grief.

Of course, this scene is nowhere in the TV show. For one thing, Ed Burns’ scripts are so intent on heroizing Alvin that this sad and grimy realism has no place in them.

The basement plays another pivotal role later in the novel, when Philip discovers the ghost of his disgraced-yet-beloved aunt Evelyn there. (Only she’s not really dead.) This scene, too, is missing from the TV show.

With all its pivotal scenes cut, you might think that the basement itself would be excised from the show, like Kevin Costner from The Big Chill. (#deepcut) “These things happen, kid, and better luck next time. Maybe they’ll need a basement in some other show.”

But no. The basement is carefully introduced in the show, along with young Philip’s fear of it… and then nothing is done with it. It’s the Chekovian gun on the wall that never goes off.

Let me pause in my relentless knifing of this show to remark that I didn’t actually hate it. As in the previous episodes, there were lots of really good things. For one thing, David Simon took over the scriptwriting in the last three episodes, and the heroizing of Alvin came to a shrieking halt. He remains an important character with a role to play in the story, but his Nazi-fighting ambitions are placed firmly into a larger context.

The show has been at some pains to establish Sandy’s alienation from his parents and his longing to climb the ladder of opportunity offered by his collaborating aunt Evelyn. (This happens in a series of beautifully written and performed scenes threaded through the Ed Burns episodes, in case you think that I have nothing good to say about that talented screenwriter.) In the last and longer half of the series (the last episode is one of those double-length things), Sandy and his parents become reconciled in an equally brilliant series of earned scenes.

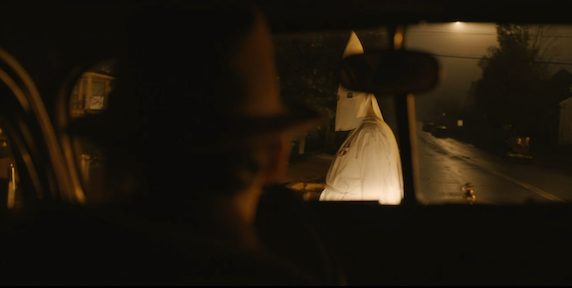

Sandy tries to avoid being noticed

by a friendly neighborhood Klansman in Lindbergh’s America.

Lindbergh disappears during one of his cross-country flights in The Spirit of St. Louis. The anti-Semitic Burton Wheeler becomes Acting President and stokes the flames of anti-Jewish hatred already burning across the country. Sandy and his dad go on a cross-country journey to rescue Seldon Wishnow, whose mother has been murdered by the Ku Klux Klan. These scenes — with a triumphant Klan burning businesses, blocking highways, threatening citizens with the open complicity of law enforcement and many hatriotic Americans — are harrowing, and more than justify Sandy’s change of heart toward his parents and their anti-Lindbergh attitudes.

Watchman, what of the night?

You may not have noticed this about my reviews so far, but I generally have felt that when the series differs from the book it starts to make mistakes — it engages in scenes that are less dramatic, characterization which is less granular and believable. With Sandy and Herman’s trek through Klanworld, the opposite is true. This stuff isn’t part of young Philip’s experience, so it’s told at one remove in the book. The show is more vivid and impactful here than the novel is.

And the showrunners are careful to avoid a feel-good ending where all the characters share a hug and realize they’ve just been through a holodeck episode. (#EverythingIsSTARTREK, only sometimes it’s really not.) On the contrary, Alvin and Herman (young Philip and Sandy’s father) come to blows in a fistfight of shocking and embarrassing violence that wrecks the family apartment. Fleeing from an anti-Semitic purge in Washington, aunt Evelyn seeks refuge in the Levin home. Her sister throws her out. Evelyn’s betrayal of her family is unforgivable. (This last is a slight departure from the novel, too, but it’s understandable, given the choices that the showrunners take in the final episode.)

In the novel, Roosevelt is re-elected in the special election of 1942 and history resumes its natural course. But the series ends on Election Day, with chicanery rampant and the results still in doubt. This would seem to be two different endings, but think it’s actually the same ending, and it’s one of the best things about the series.

I talked above about the ironic tension in the novel between Philip-the-character and Philip-the-narrator. There’s another tension, equally important, between Roosevelt’s America and Lindbergh’s America. The one was real. But the other isn’t some kind of imaginary dystopia: it, too, was real, a Nazistic Fifth Column inside America that never went away. Every American Jew has spent some time in that far-from-imaginary country.

Similarly: the series ends with an election that didn’t ever really happen, the Presidential Election of 1942. There were all sort of indications that the outcome was in doubt, along with open instances of voter suppression.

It won’t have escaped your notice that there is a US Presidential election underway currently in 2020. There are all sorts of indications that the outcome is in doubt, along with open instances of voter suppression.

Everything I said above about the series is true, but it’s also misleading. This isn’t a story about some far-off political conflict that happened before most living Americans were born. It’s a story about today, and the end is not yet. Soon, maybe, but not yet.