Shabtis: Servants in the Ancient Egyptian Afterlife

Some very bling shabtis from the 18th dynasty tomb of Yuya and Thuya

We all know the ancient Egyptians were obsessed with death. What with their elaborate spells, mummification, and tomb preparations, you’d think that the Egyptian afterlife would be one big vacation. After all that preparation they deserved a bit of rest.

Not so. The gods subjected the deceased to all sorts of jobs and obligations. The afterlife was just like our world, where all the usual cultivation and manufacturing had to be done. If you didn’t want to spend eternity doing manual labor, you needed to have some hired help.

Late Period shabtis from the tombs of the Nubian pharaohs of the 25th dynasty

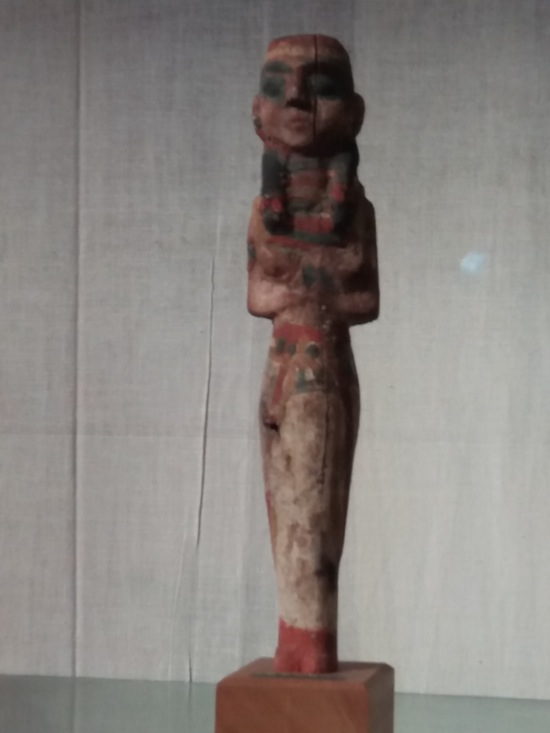

Enter the shabti (also called ushabtis at various times), a small figurine that acted as a servant in the afterlife. “Shabti” means “answerer”, someone who answers the call to work. Shabtis were small figurines about 4-12 inches tall and made of wood, faience, wax, terracotta, or stone. People of all social classes were buried with them, and they come in an astonishing variety of styles and quality. The vast majority were mummiform in shape, with a clearly recognizable head and arms folded across the chest, with the body and legs as one shape as if bound by wrappings. Some were equipped with little tools to help them with their work. Shabtis often had a spell written on the legs and torso.

Shabtis first appeared in the early Middle Kingdom (c. 2000 BC), when only one or two examples would be put in the tomb. They gradually grew in popularity and number until by the Late Period (c. 712-332 BC) the optimum number of shabtis for the tomb was 401. This was one shabti for each day of the year plus an overseer shabti for each ten grunt laborer shabtis. You could tell the overseers by the little whip they carried. Some collections could be even larger. Tutankhamun (c. 1332–1323 BC) had 413, some elaborately covered in gold foil while others were plainer faience. Seti I (c. 1294-79 BC) had more than 1,000 shabti in his tomb. Large collections were often kept in specially decorated boxes. Shabtis continued to popular throughout the Ptolemaic period (310-30 BC) before gradually dying out.

Shabti box with collection of faience shabtis. From the

tomb of Pinedjem I, 21st dynasty. He was one of the many rival,

self-proclaimed pharaohs of the Third Intermediate Period and

ruled from from the city of Tayu-djayet (el-Hiba)

Shabti from the 25th dynasty

Horudja, a priest of the goddess Neith during the 30th Dynasty (380-343 BC) had 399 shabtis in his tomb. They were inscribed with three slightly different spells. The following was the most common and is typical of the spells found on other shabtis. It is from the 6th chapter of the Book of the Dead:

“The illuminated one, the Osiris, the Priest of Neith, Horudja, born to Shedet, justified, he says: O these ushabtis, if counted upon, the Osiris, the Priest of Neith, Horudja, born to Shedet, justified, to do all the works that are to be done there in the realm of the dead – now indeed obstacles are implanted there – as a man at his duties, ‘here I am!’ you shall say when you are counted upon at any time to serve there, to cultivate the fields, to irrigate the river banks, to ferry the sand of the west to the east and vice–versa, ‘here I am’ you shall say.”

Shabtis from Saqqara, 19th dynasty

Shabti from the 19th dynasty, Saqqara

Shabtis from the tomb of Tutankhamun. As you

can see, he got quite a variety! This may be due to

the haste with which he was buried. The priests may

have grabbed whatever good quality shabtis they had at hand

Shabtis covered in gold foil from the tomb of Tutankhamun

Because they are common, attractive objects, shabtis have long been popular with collectors. Antique stores and Ebay auctions often have them for sale at reasonable prices in case you’re interested. Knowing how many artifacts on the antiquities market are either stolen or fake, I’ve resisted temptation. I must admit that I’ve been tempted, though!

All photos copyright Sean McLachlan and were taken at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. You can see some more shabtis in my article about the Petrie Museum in London. More pictures of Egypt next week, plus many more on my Instagram account!

Sean McLachlan is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and several other titles. His novel set in Tangier, The Last Hotel Room, examines the human side of Middle Eastern politics. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page.