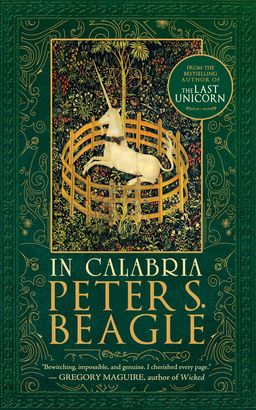

Something Terrifying and Wonderful: In Calabria, by Peter S. Beagle

Peter S. Beagle has, by dint of his enduring classic The Last Unicorn, become the patron saint of these creatures among fantasy authors. But more than this, Beagle has become to fantasy writing a sort of patron saint of the longing that unicorns (when exhumed from the candied, polychromatic encrustations of the popular imagination) have come to embody. Beagle has resurrected the unicorn as a symbol to be reverenced, whether in his early novel or, as I have argued recently in another review, in the person of Lioness in his recent Summerlong. Unicorns represent the quiet desperation for a touch of otherworldliness, of the desire for something beyond or above or even just beside to press up against our daily lives. It is this longing for visitation that runs through his latest work, the short book In Calabria, and plays out on the confines of a rustic farm and in the life of a single isolated farmer.

Peter S. Beagle has, by dint of his enduring classic The Last Unicorn, become the patron saint of these creatures among fantasy authors. But more than this, Beagle has become to fantasy writing a sort of patron saint of the longing that unicorns (when exhumed from the candied, polychromatic encrustations of the popular imagination) have come to embody. Beagle has resurrected the unicorn as a symbol to be reverenced, whether in his early novel or, as I have argued recently in another review, in the person of Lioness in his recent Summerlong. Unicorns represent the quiet desperation for a touch of otherworldliness, of the desire for something beyond or above or even just beside to press up against our daily lives. It is this longing for visitation that runs through his latest work, the short book In Calabria, and plays out on the confines of a rustic farm and in the life of a single isolated farmer.

Claudio Bianchi is an old man. He lives alone on a hillside farm in Calabria, the region of Italy forming the mountainous toes of the country’s famous boot outline. Calabria is scenic and slow, off the beaten path. Beagle plays into the timelessness of the place. His protagonist is timeless and isolated as well: solitary, cranky, and proud of the tiny, half-ruined farm he cultivates in the same manner his ancestors did a hundred years before. Beagle, who has had his share of trouble lately and perhaps longs for the sort of escape Bianchi’s life represents, sets a stage of idyllic isolation in rustic Mediterranean splendor. “The universe and Claudio Bianchi had agreed long ago to leave one another alone,” we are told early on in the story. “And if he had any complaints, he made sure that neither the universe nor he himself ever knew of them.”

It is not, however, this isolation and timelessness alone that draws a unicorn to Bianchi’s farm to give birth. Rather, Beagle leads the reader to understand it is Bianchi’s crusty humility and his compassion for and amiable companionship with the animals that share his land. It may also be because Bianchi is a poet. His reputation as such among his neighbors is something of a puzzle, as he never shares his poems or publishes them. He simply takes pleasure in fitting words together, in working them the way he works the soil, and leaves them hidden in the drawers of his desk. For perhaps all these reasons, a unicorn appears in Calabria and chooses a hollow in view of Bianchi’s back window to give birth to her young. “I am past visitations,” Bianchi asks the pregnant unicorn when it first arrives. “What do you want with me?”

In this first portion of the work Beagle’s pacing is measured and his language equal to the task of conveying what could easily be just a trite pastoral. We see the encounter through Bianchi’s weathered, disbelieving but ultimately resigned eyes. No one else sees the unicorns except for a brief glimpse by Romano Muscari, Bianchi’s mailman and one of his few friends. Muscari’s younger sister, Giovanna, however, becomes a companion in the secret, visiting Bianchi’s farm regularly to watch the unicorns with him.

Yet soon, inevitably and inexplicably, everyone knows that Bianchi’s tiny farm harbors unicorns. An army of searchers, reporters, cameramen, and adventurers invades Bianchi’s land. Though the rest of the work is well paced, this abrupt development seems like a slippage, like an escalation toward crisis without any build-up or tension. One day Bianchi is alone with the unicorns; the next, the farm is flooded by a tide of hunters with television vans, microphones, dirt bikes, and harpoon guns. Of course, there’s no chance of any of these invaders finding the unicorns, so it all starts to feel like surreal background noise, irrelevant and futile.

The story isn’t carried by any real fear of a destructive encounter between the modern world and the unicorns. Indeed, we never are given a glimpse of the modern world’s perspective, of how the possibility of unicorns on an isolated farm appears or is reported to the modern world. The perspective remains Bianchi’s, to whom the reporters and searchers are as foreign and unknowable as the unicorns themselves. Bianchi has already turned his back on the world they represent, offering an atonement to the unicorns in one of the few poem fragments were are given a glimpse of: “As you claim all lands stolen / from you / by those who only gift is for stealing beauty / take it back from me now.” The unicorns find his land, but they are sheltered there because Bianchi recognizes what the rest of the world cannot — that it was never really his to begin with.

In Calabria quickly becomes not so much about the unicorns as about Bianchi’s two additional encounters that follow from the unicorns’ visitation. The first of these is with Giovanna. Like the unicorns, the young Giovanna becomes a breaking in of something terrifying and wonderful upon Bianchi’s entrenched isolation. “Do you know,” Bianchi asks the unicorns at one point, though as the story progresses he may as well be speaking to Giovanna, “do you ever consider, how beautiful and impossible you have made my life? Do you care?” The unicorns chose Bianchi’s farm, but Giovanna does something that to the old, crotchety Bianchi appears even more remarkable: she chooses Bianchi himself. Their growing relationship, despite the twenty-three year gap in their ages (and despite or because it perhaps represents dreams of an old writer), is believable, expertly crafted, and gives rise — as is the case in so much of Beagle’s work — through their conversations and Bianchi’s musing on it to some of the most poignant scenes of the work. It is a mark of Beagle’s genius that he can write a work in which the conversations between new lovers across the dinner table reads just as powerfully as the scene of a unicorn’s birth.

In Calabria quickly becomes not so much about the unicorns as about Bianchi’s two additional encounters that follow from the unicorns’ visitation. The first of these is with Giovanna. Like the unicorns, the young Giovanna becomes a breaking in of something terrifying and wonderful upon Bianchi’s entrenched isolation. “Do you know,” Bianchi asks the unicorns at one point, though as the story progresses he may as well be speaking to Giovanna, “do you ever consider, how beautiful and impossible you have made my life? Do you care?” The unicorns chose Bianchi’s farm, but Giovanna does something that to the old, crotchety Bianchi appears even more remarkable: she chooses Bianchi himself. Their growing relationship, despite the twenty-three year gap in their ages (and despite or because it perhaps represents dreams of an old writer), is believable, expertly crafted, and gives rise — as is the case in so much of Beagle’s work — through their conversations and Bianchi’s musing on it to some of the most poignant scenes of the work. It is a mark of Beagle’s genius that he can write a work in which the conversations between new lovers across the dinner table reads just as powerfully as the scene of a unicorn’s birth.

Bianchi’s second visitation ratchets up the story’s stakes and provides it with some timely urgency where it might have otherwise dragged just past its midpoint. This visitation is by the underbelly of organized crime in Calabria (not the Sicilian mafia, Beagle is at pains to specify, but rather the Calabrian ‘Ndrangheta). A farm reported to be home to unicorns, whether those unicorns are ever observed, is worth a fortune. But once Bianchi — not from bravery, but, as he says, from stubbornness and stupidity — refuses their offer to buy his farm, he becomes marked as a dead man. Now the farm with its unicorns becomes an enclave under a much more pointed threat. What clueless intruders could not find, faceless monsters might destroy. Bianchi’s cat is mutilated, Bianchi himself is beaten in the middle of the night, and the villagers give him the honors and respect due one condemned to death.

Bianchi’s character remains consistent, but the book’s conclusion is problematic. The conclusions in Beagle’s works are usually straightforward, not so much the collisions of implacable forces as the inexorable restoration or outworking of the nature of things themselves. Ghosts fade with time. Unicorns are returned to the world. Persephone returns to Hades as the seasons change. In Calabria is a bit of a twist on this. Bianchi, we know, will not negotiate or outsmart or escape the ‘Ndrangheta, but neither will the unicorns magically come to his rescue. Yet the farmer, in the final climax, pinned between the unicorns and the weapons of the thugs who have come to take his farm, quietly and desperately does something unexpected: he presumes to ride the unicorn. What happens after that is unclear, both to Bianchi and to the reader. A transformation of some kind takes place in which it seems that Bianchi and the (to this point unseen) father unicorn are briefly melded. The ‘Ndrangheta flee in terror, and the unicorns quite literally drift into the sunset.

Bianchi’s isolation is effectively ended. The unicorns have touched him, and he cannot be the same person he was before. His land will be forever blessed for having been the spot where a unicorn was born. Giovanna will remain, at least as long as she can. As far as all that goes, I was satisfied. But what secret did the unicorns leave Bianchi with? There is a passage, in a scene in which Bianchi is trying to get the unicorns to leave his farm for their own safety, where he looks into the eyes of the female unicorn and has an epiphany:

That is why men hunt unicorns, and why they will always kill them when they capture them. Not the beauty, not the magic of the horn . . . [sic] because of what lives and waits in the eyes. Finally I understand.

But the reader is left guessing at what, exactly, Bianchi has learned.

Stephen Case has published fiction at Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Orson Scott Card’s Intergalactic Medicine Show, and Daily Science Fiction. His reviews have appeared at Fiction Vortex and Strange Horizons, as well as his own blog, stephenreidcase.com.

[…] Fiction at Tor.com. Stephen Case reviewed Peter Beagle's most recent novel, In Calabria, for Black Gate. John Rieder's imminent new book is Science Fiction and the Mass Cultural Genre System, which I […]