A State of Suspension: Iain Banks’ The Bridge

|

|

|

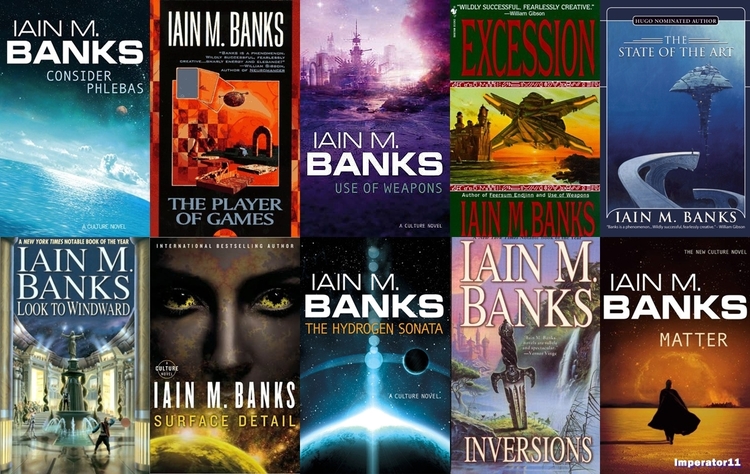

Iain Banks, the Scottish science fiction writer, established himself as a major presence in the genre with his Culture series, the first of which, Consider Phelebas, appeared in 1987. Set in a far future, post-scarcity universe teeming with human and alien societies, the Culture books are wide screen space operas with a decidedly sociological-political perspective. Banks wrote a new Culture book every few years until there were ten volumes. The final one, The Hydrogen Sonata, appeared in 2012, shortly before Banks died of cancer in 2013, at the age of 59.

In 1986, right before beginning the series that would dominate the rest of his career, Banks published something rather different: The Bridge, a book that stands high in the ranks of a significant sub-genre of fantasy, those stories that deal with pre or after life states, or that take place in the nebulous regions between life and death.

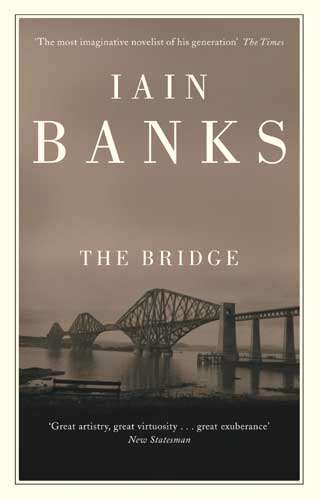

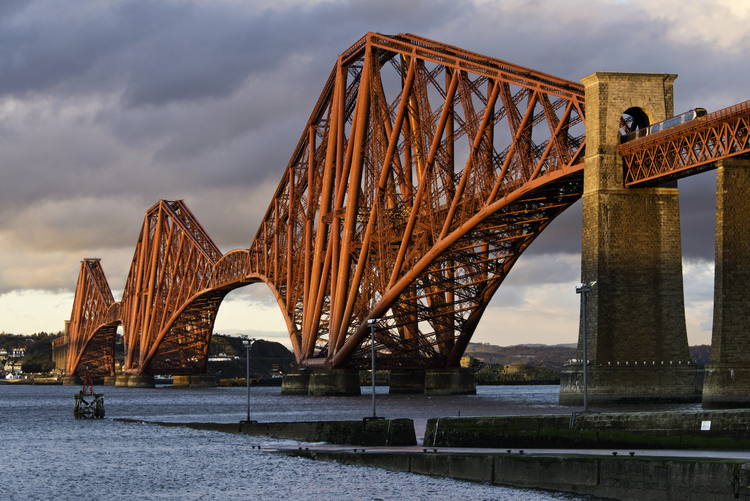

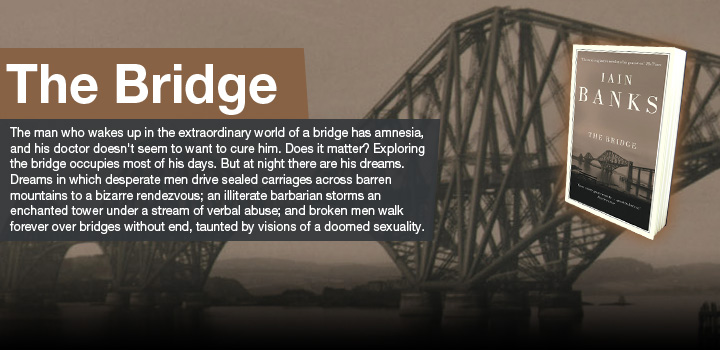

The Bridge begins as a nameless man (we eventually learn that he is an affluent Glasgow professional named Alex) has a moment of inattention while driving back from a weekend of nostalgic dissipation; as he gazes at the Forth Railway Bridge that crosses the Firth of Forth just west of Edinburgh, he fails to notice the shifting traffic patterns in front of him and crashes his car. He is trapped in the wreckage of his vehicle, praying that it doesn’t burst into flames before he can be rescued. Crushed and bleeding, he lapses into unconsciousness… and awakens, whole and uninjured, on the bridge.

Forth Bridge, Scotland

An enormous structure with roads and rail lines, level after towering level of factories and shops and restaurants and apartments and offices, its own economy and social system and politics and customs and taboos, the bridge seemingly has no end and no beginning, in time or in space; it stretches over a vast ocean, linking The City and The Kingdom, neither of which are ever seen (until just before the novel’s close) — each end of the bridge vanishes into a far horizon on which no land is visible. The man from the car wreck has no memory of his name or his history, or knowledge of anything outside of the bridge. The doctors on the bridge dub him John Orr, and he spends his time trying to recover his memories and uncover the history and purpose of the bridge, both tasks proving impossible to accomplish, especially as he is impeded at every step by both the sinister and obfuscatory bureaucracy in which he finds himself enmeshed and by his own barely acknowledged reluctance to find out the truth about himself and his situation.

He is in fact in a coma (no spoiler here, friends — the first thing you read, before even the first page of narrative, is the opening section’s subtitle: “Coma”) and in this state of suspension between life and death, Orr/Alex is reconstructing his own personality and his own past — as the bridge. As he relives and resolves his personal conflicts in this symbolic fashion, he fights back to the surface of consciousness, trying to return to the “real” life that he has forgotten, even as part of him doesn’t want to awake to the muddled, compromised existence he experienced before the accident. (When he does awaken, he thinks, “Oh God, back to Thatcher’s Britain and Reagan’s world, back to all the usual bullshit. At least the bridge was predictable in its oddness, at least it was comparatively safe.)

In such a bare outline The Bridge may sound schematic to the point of obviousness, but it’s full of surprises and lively, unexpected turns. The story is told with verve and inventiveness and great humor too — in his coma “life” Orr has a recurring dream within his dream, of himself as a barbarian warrior (called “the Barbarian” naturally), a sort of dunderheaded Conan figure who speaks with an outrageous Scottish accent; these sections are hilarious send-ups of sword and sorcery cliches.

The book isn’t without flaws; the central psychological conceit is perhaps a bit too pat (sort of like Rosebud in Citizen Kane, which Orson Welles always dismissed as “dollar-book Freud” and declared was the weakest part of the film), and the short “real-world” sections dealing with Alex’s life before the accident aren’t particularly engaging; he is too much of a standard type for me to care much about, and unlike the events in his coma his “real” life’s history feels rote and predictable (prosperous left-wing engineer slides into an aimless, sold-out middle age while struggling with personal and political commitments… yawn).

Iain Banks

But the bridge itself is a fabulous creation, with its arcane class system, its hidden history with secrets and mysteries and dead ends that are worthy of Kafka or Borges, its endless levels and corridors and clubs and room-sized, furnished elevators, its luxurious apartments with windows that look out over an endless, shoreless sea, its oddly pleasant blend of nineteenth and twentieth century technology (at one point, Orr looks away from his television set to glance out of his upper-level apartment’s window, where he sees propeller-driven monoplanes sputter past), its weather of rains and mists and fogs…

Alex’s problems and guilts and conflicts may be bland, but the dream venue in which he resolves them isn’t; the bridge is constantly surprising and endlessly fascinating. The bridge is what made The Bridge such a good book — I wish I could have spent more time exploring it. It would have been fine with me if Alex had never woken up and stayed John Orr; liberal upper-middle class engineers are a dime a dozen, but wonderful constructs like the bridge come along all too rarely. (In this respect, The Bridge made me think of Steven King’s The Shining. In both cases I found the setting much more engaging than the protagonist. I very quickly found out more than I wanted to know about Jack Torrance; it was the Overlook Hotel that I could never find out enough about.)

The Culture Series

At the end of the book, awake in the hospital, Alex realizes that he isn’t now abandoning a dream for reality — he’s simply exiting a private dream and reentering the common one we all share:

One is my own; the bridge and all I made of it. The other is our collective dream, our corporate imagery. We live the dream; call it American, call it Western, call it Northern, or call it just that of all we humans, all life.

We all daily go about the task of inventing, interpreting, and integrating who and what we are, so as to be able to make sense of the world around us; we just do it, as now Alex must, with our eyes open.

When Iain Banks died he left behind many fine books, many dreams for all of us to share and profit from, but I wouldn’t be surprised if he were remembered most for the intricate, alluring dream he called The Bridge.

Thomas Parker’s last article for us was How We Got Where We Are, or Go Adam West, Young Man

This would be my favourite Banks novel, for the reasons you say, and especially for the Scottish barbarian – presumably meant to represent Alex’s primal self but worthy of a book in his own right. And who could forget his companion, the talking dagger? (The barbarian insists the dagger is deluded, that it is in fact, a dirk).

Just started reading The Bridge. Better late… Ian is the man. I am not sure there is a better writer … RIP