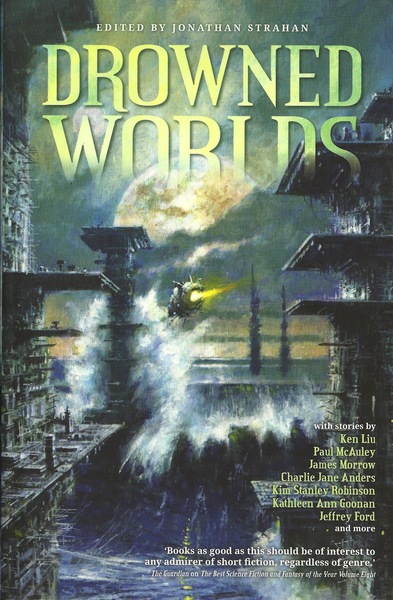

Distinctive Visions of Earth After Climate Change: Drowned Worlds, edited by Jonathan Strahan

|

|

Reading reviews frequently helps heighten my anticipation for a book. That’s certainly the case with Jonathan Strahan’s acclaimed new anthology Drowned Worlds, a collection of SF tales which looks at the future of Earth after the full effects of climate change.

The book includes all-new fiction from Ken Liu, Kim Stanley Robinson, Christopher Rowe, Kathleen Ann Goonan, Charlie Jane Anders, Jeffrey Ford, Rachel Swirsky, Lavie Tidhar, Catherynne M. Valente, and many others. It’s been getting some terrific reviews, from places like Tor.com, Locus Online, and other fine institutions. Here’s a few samples, starting with author James Lovegrove in the Financial Times.

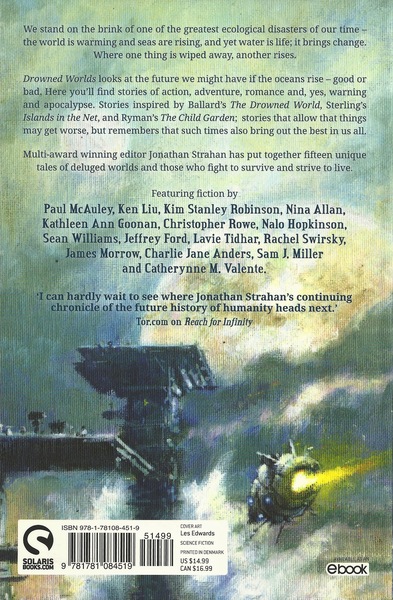

Taking its cue — as well as its title — from JG Ballard’s 1962 debut novel The Drowned World, the book offers 15 memorable, distinctive visions of Earth after climate change has exerted its grip. Sea levels have risen, and deserts have spread. People live aboard rafts, amid ruins, on other planets. The Anthropocene era has done its apocalyptic worst. There is nevertheless, a thin silvery thread of hope — humankind, through its adaptability and ingenuity, endures.

And here a snippet from Gary K. Wolfe’s lengthy review at Locus Online.

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

Strahan’s anthology opens with Paul McAuley’s wonderfully titled “Elves of Antarctica,” in which climate change refugees have begun to settle into a newly temperate Antarctica, complete with reconstituted mammoths, where a number of stones have been discovered marked with mysterious runes that for some evoke the huldufolk of Iceland, while others suspect they may simply be hoaxes derived from a very familiar fantasy movie trilogy. Like most of the stories here, it’s set in a recognizable mid-distant future, but Ken Liu’s “Dispatches from the Cradle: The Hermit – Forty-Eight Hours in the Sea of Massachusetts” takes us all the way to the 27th century, when the solar system is colonized and refugees have established huge floating colonies over their drowned homelands. The central figure is very much a Ballardian character, a famous hermit who has taken up residence in the sea above what was once Harvard University. The setting for Christopher Rowe’s “Brownsville Station” is a vast Gulf of Mexico megalopolis stretching from Cancun to Key West, but in a world in which weather has become so violent that the only safe method of travel is by train. In Charlie Jane Anders’s “Because Change Was the Ocean, and We Lived by Her Mercy,” the new megacity is Fairbanks, but what is most striking about this story is not the architecture of the lost world, but its music: the main characters, the Wrong Headed kids, are inept musicians trying to recreate something of what was lost, not only in the flooding but in a worldwide ‘‘dataclysm’’ that virtually lost all digitally stored music. And perhaps the most original version of a post-apocalyptic megacity here is the Garbagetown of Catherynne Valente’s “The Future Is Blue,” a surreal conglomeration of waste and junk built on the famous Pacific garbage patch; Valente’s young narrator, though, believes it to be ‘‘the most wonderful place anybody has ever lived in the history of the world’’ – possibly the most direct ironic expression of Ballard’s notion of archaeopsychic transformation.

And here’s Brit Mandelo, over at Tor.com.

This anthology is a quick, engaging, immersive read… There were a few pieces that lingered with me longer than the rest, including Charlie Jane Anders’ “Because Change Was the Ocean and We Lived by Her Mercy.” As an approach to communal living, growing up, and the strange shifts of human culture in a post-flood world, this is top-tier work. It’s domestic, personal, and witty. The protagonist discovers plenty about the world around them, the vagaries of people being together with people and the tides of little communities. It’s intimate, it’s clever, and it gives me a more realistic and honest approach to the whole “commune life” idea than I often see. I also appreciated the acknowledgement of a spectrum of genders and approaches to presentation that’s just natural background in the piece.

“Venice Drowned” by Kim Stanley Robinson, on the other hand, is intimate in a more traditionalist sense. This feels like a piece that could be historical fiction, except it’s set in the post-deluge future. The protagonist’s attachment to his drowned culture, particularly as revealed in the conflicts over tourism and wealth, all come together in an intriguing fashion. His rough ease with his family, his community, and his survival on the waters are all somehow quiet and close to the reader despite their occasional brusqueness.

“Inselberg” by Nalo Hopkinson is the closest to horror of the bunch, with its tourist-eating landscapes and capricious magics told through the guide’s narration. I appreciated the sense of being an audience member that the point of view gives; it builds the tension with fantastic skill, and it’s hard to slip free of the grip of the narrative winding you in tight. Solidly creepy, a fine compliment to all of the rather soft-edged stories here. “Inselberg” also addresses issues of colonialism and submerged histories in a way that is smart and incisive, amongst its disturbing occurences.

Here’s the complete Table of Contents.

“Elves of Antarctica,” Paul McAuley

“Dispatches from the Cradle: The Hermit – Forty-Eight Hours in the Sea of Massachusetts,” Ken Liu

“Venice Drowned,” Kim Stanley Robinson

“Brownsville Station,” Christopher Rowe

“Who Do You Love?,” Kathleen Ann Goonan

“Because Change Was the Ocean and We Lived by Her Mercy,” Charlie Jane Anders

“The Common Tongue, the Present Tense, the Known,” Nina Allan

“What is,” Jeffrey Ford

“Destroyed by the Waters,” Rachel Swirsky

“The New Venusians,” Sean Williams

“Inselberg,” Nalo Hopkinson

“Only Ten More Shopping Days Left Till Ragnarök,” James Morrow

“Last Gods,” Sam J. Miller

“Drowned,” Lavie Tidhar

“The Future is Blue,” Catherynne M. Valente

Our recent coverage of Jonathan’s books includes:

The Most Successful Anthology of 2015: Meeting Infinity

The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year: Volume Ten

A Concentrated Dose of the Best Our Field Has to Offer: Jonathan Strahan’s Best Short Novels 2004-2007

Future Treasures: Meeting Infinity

The Early Jack Vance, Volume 4, edited by Terry Dowling and Jonathan Strahan

The Early Jack Vance, Volume 5, edited by Terry Dowling and Jonathan Strahan

Fearsome Magics: The New Solaris Book of Fantasy

Reach For Infinity

The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year Volume 8

Fearsome Journeys: The Solaris Book of Fantasy

Swords and Dark Magic, edited by Jonathan Strahan & Lou Anders

Drowned Worlds was published by Solaris Books on July 12, 2016. It is 336 pages, priced at $14.99 in trade paperback and just $6.99 for the digital edition. The cover is by Les Edwards.

See all of our coverage of the best in new fantasy here.

I just read Ballard’s original novel this past year. I think it’s most remembered for being prescient, at least that’s how we see it now. But I was struck by how “adult” or mature the style of writing felt compared to other SF in that day. You felt that this was a serious writer giving a serious story–it just happened to be in a sci-fi setting.

I know Ballard was considered part of the British new wave at the time. If Ballard is a good representation of the new wave, I think I can begin to understand Moorcock’s grumblings about general sci-fi and fantasy of the time. Perhaps the new wave was trying to take itself more seriously.

Or, maybe I’m completely off the mark.

I need to read more Ballard! I spent the last few weeks tracking down this enticing and elusive UK paperback.

I finally found a copy on eBay for 5 cents (plus $3.99 shipping… not a bad deal), and now it is mine.