Reading Burroughs’ Biography as a Writer

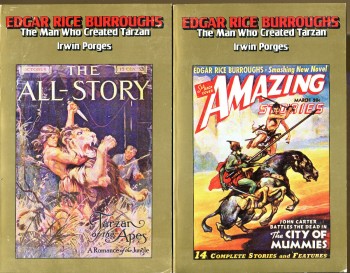

About eight years ago, when I was struggling to get my short stories published, I picked up the two-volume biography of Edgar Rice Burroughs by Irwin Porges. I think I’d been looking for some communion with a writer I’d enjoyed as a teen; I got that and more, including a reassurance that I was on the right track.

About eight years ago, when I was struggling to get my short stories published, I picked up the two-volume biography of Edgar Rice Burroughs by Irwin Porges. I think I’d been looking for some communion with a writer I’d enjoyed as a teen; I got that and more, including a reassurance that I was on the right track.

Now, it’s difficult to discuss Burroughs in any setting without dropping some pretty big caveats. Burroughs was a product of his time, and it wasn’t a good time. By way of example, he wrote A Princess of Mars in 1911, a time when women and minorities could not vote in Canada, and a time when Jim Crow laws in the United states wouldn’t be repealed for another 50 years. His great white male hero appeared in most of his popular stories and his depiction of anybody who wasn’t white was rife with stereotypes and/or condescension.

Those facts exist and make it a big reason why I can’t show my son much of ERB’s work without heavy discussions, or by using them as counter-examples of the way life ought to be. But, at the same time, I did read and enjoy ERB from the time I was 11 to the time I graduated to more sophisticated works in high school.

Those facts exist and make it a big reason why I can’t show my son much of ERB’s work without heavy discussions, or by using them as counter-examples of the way life ought to be. But, at the same time, I did read and enjoy ERB from the time I was 11 to the time I graduated to more sophisticated works in high school.

And the chance to see inside this prolific creator, while I was an insecure writer trying to be a prolific creator, was really something I was looking forward to.

Porges’ biography, based on access to ERB’s meticulous files, begins as early as one can go, and takes until the start of chapter six (p. 174) to get to his first writings. This was a bit startling to me. From the time I was 9 or 10, I knew I’d wanted to be a writer. ERB didn’t come to that decision, and came to it only because he’d failed at every business venture, until he was 35 years old.

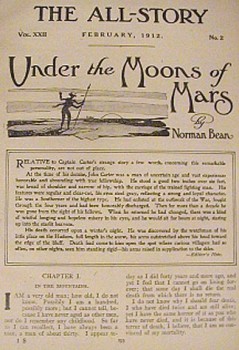

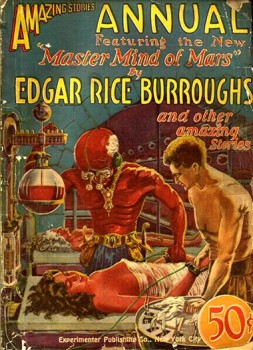

He wrote A Princess of Mars in 1911 when he was down on his luck, unable to feed his new family, and unsure of anything in the publishing world. He was rejected by Argosy, but sold it to All-Story Magazine for $400 (which is about the same as $9,600 now). This sale led him to decide to be a writer.

It’s funny though to see him deal with problems like the publisher messing up his pen name – he was so embarrassed of his story that he wanted his nom-de-plume to be Normal Bean, but the copy-editor thought it was a typo and changed it to Norman Bean. As that was wrecked, he quickly switched to his real name.

As a writer struggling with rejection and forcing myself to believe in my work, I was completely intrigued by Burroughs’ reaction to rejection. First of all, I was happy to see he got rejected a lot. He kept on trying to put his stories in higher-paying magazines and kept on getting turned down.

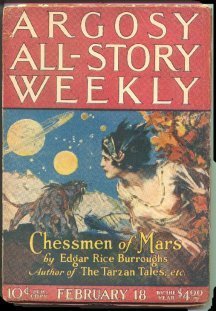

In hindsight (or even contemporary-sight, it’s pretty clear that he wasn’t writing literature, and he knew it, but he still sent his stuff to some big magazines). He felt trapped by constantly being stuck selling to All-Story and occasionally Argosy.

His next novel, Outlaw of Torn, was so uncommercial and derivative that he spent a long time (for him) trying to publish it. Most writers faced with the specific, pointed rejections that reveal flaws in works would have thrown those novels in a trunk (we all have such novels), but this revealed another surprising feature of Burroughs’ character: he was a merciless businessman and he pushed and pushed and pushed editors to give him his price. This became easier after John Carter and Tarzan took off, but what is striking is that he was doing this even in the beginning.

He next wrote Tarzan of the Apes, something so spectacularly original, that despite having sold two novels to magazines, he appears in more than a few moments to have faltering confidence in it. Luckily, he had an encouraging editor and after five and a half months of work, he sold it for $700 ($16,800 now). It was published in October, 1912.

He next wrote Tarzan of the Apes, something so spectacularly original, that despite having sold two novels to magazines, he appears in more than a few moments to have faltering confidence in it. Luckily, he had an encouraging editor and after five and a half months of work, he sold it for $700 ($16,800 now). It was published in October, 1912.

Having sold magazine rights, Burroughs took his published works and went from book publisher to book publisher, experiencing what most writers experience: rejection after rejection and finally, having no more publishers to go to.

This was depressing for him, and for us, looking back from a historical view, surprising. But he launched into his next stories, which were quite in demand, considering he ended A Princess of Mars on a cliff-hanger, and did the same with The Gods of Mars and didn’t give a satisfying conclusion until Warlord of Mars.

Burroughs took a fair bit of criticism from critics and his own editors about the speed and lack of care with which he wrote, so much so that All-Story initially rejected The Return of Tarzan because the editor wanted rewrites and polishing.

Interestingly, Burroughs calculated his writing earnings by the hour, so if he wasn’t forced (or paid) to do rewrites, he didn’t do them, and it doesn’t look like he did much more than a quick typo-seeking pass on his first drafts.

It caused a bit of grief when ERB turned around and sold The Return of Tarzan to a different magazine (New Story). This tough businessman attitude is characteristic of Burroughs throughout his career and editors had to learn to deal with ERB on his terms and not on theirs — Tarzan was too popular. I did not take this as a lesson that would serve me in my budding writing career…

It caused a bit of grief when ERB turned around and sold The Return of Tarzan to a different magazine (New Story). This tough businessman attitude is characteristic of Burroughs throughout his career and editors had to learn to deal with ERB on his terms and not on theirs — Tarzan was too popular. I did not take this as a lesson that would serve me in my budding writing career…

As an example of his tough negotiating, when he had sold The Return of Tarzan to New Story, he then submitted The Outlaw of Torn to them, which had been rejected everywhere else.

New Story offered $350 for it. Burroughs said he would give them Outlaw for $1,000 and the sequel to The Return of Tarzan for $3,000 as a package deal. New Story eventually came up to $500 for Torn, and Burroughs finally accepted.

Burroughs continued to try to maximize his profits and he began to sell newspaper rights to his novels and his stories began going into the newspapers of big cities.

This was good for money and good for creating a further market for Tarzan, but when Burroughs tried to argue this to book publishers, they rejected him cold again, saying (incredibly!) that because the novel had already appeared in newspapers, no one would buy the book. Again, 20/20 hindsight, but… wow.

Spoiler alert: He eventually did crack the novel market. The publishers came back to him when they saw how famous Tarzan was becoming, and they ended up publishing most everything he had and then foreign sales and that money came in too.

Spoiler alert: He eventually did crack the novel market. The publishers came back to him when they saw how famous Tarzan was becoming, and they ended up publishing most everything he had and then foreign sales and that money came in too.

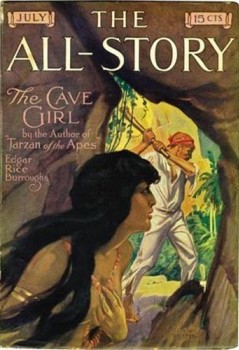

He kept creating new worlds such as The Cave Girl and The Inner World, and writing more Tarzan and Barsoom stories and this is where people call Burrough prolific. Well, he was. In the first half of 1913, he wrote 186,000 finished words (in today’s terms, that’s two novels), and by the end of the year, he’d written 413,000 words (basically, the equivalent of 4-5 modern novels).

I’d always been a bit intimidated by his output, but when I did the math, I realized that as a full-time writer, he was producing about 1,100-1,200 finished words per day.

By the time I first read the biography, I was already producing 300-500 words with a full-time job. Now on a writing sabbatical, I’m easily producing 1,500-2,000 words of first draft per day. This, perhaps more than all the other struggles Burroughs dealt with, was what most reassured me that I could be a writer and produce at whatever speed worked for me.

I highly recommend the Porges biography of Burroughs for writers and aficionados of ERB.

Derek Künsken writes science fiction and fantasy in Gatineau, Québec and is on a 2-year sabbatical to spend time with his son and to write more. He’s been published multiple times in Asimov’s Magazine and got the Asimov’s Readers’ Award in 2013. He tweets from @derekkunsken.

I read that bio when it first appeared and bought a copy of the boxed 2-volume paperback as soon as I could. A wonderful book.

Thanks. I love a good bio of a writer. I’ll have to check that one out.

I think the best non-biographical book on ERB is Master of Adventure by Richard Lupoff. It’s a general look at Burroughs’ work by a non-blinkered admirer. It’s available in a nice paperback edition from the University of Nebraska’s Bison Books.

Bill: I totally agree.

Amy: Totally recommended. I admit I did skip the first couple of chapters – I wanted to get to his decision to be a writer 🙂

Thomas: I hadn’t heard of that one. I’ll check it out!

Derek