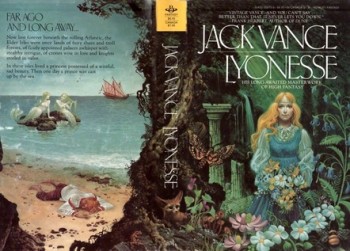

Lyonesse: Suldrun’s Garden by Jack Vance

Lines from the song “Comedy Tonight” from A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum sprung to mind numerous times this past week while I was reading Jack Vance’s Lyonesse: Suldrun’s Garden (1983). While definitely not a comedy, it is by turns familiar and peculiar, convulsive and repulsive, as well as dramatic and frenetic. And sometimes, very funny. It is also one of the most inventive, strange, and bewitching books I have had the joy to read.

Lines from the song “Comedy Tonight” from A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum sprung to mind numerous times this past week while I was reading Jack Vance’s Lyonesse: Suldrun’s Garden (1983). While definitely not a comedy, it is by turns familiar and peculiar, convulsive and repulsive, as well as dramatic and frenetic. And sometimes, very funny. It is also one of the most inventive, strange, and bewitching books I have had the joy to read.

His first collection, the fantasy classic The Dying Earth (which you can read about in John O’Neill’s post here), helped make Vance’s early reputation as a writer of lapidarian prose, cynical wit, and above all as an inventor of incredibly original cultures, worlds, and characters. For the next three decades of his career he seemed to eschew straight fantasy, and most of his published work was science-fiction and mysteries. In 1983, though, he released a lengthy work of fantasy, Lyonesse: Suldrun’s Garden (L:SG). It rapidly shifts from studies of realpolitik, to fey whimsy, to dark violence that might make George R.R. Martin blush, yet it’s never jarring but completely complementary and intoxicating.

Over the following six years he added two sequels, The Green Pearl (1985), and Madouc (1989). With the latter, Vance beat out Gene Wolfe, Tim Powers, and Jonathan Carroll, among others, to win the 1990 World Fantasy Best Novel Award.

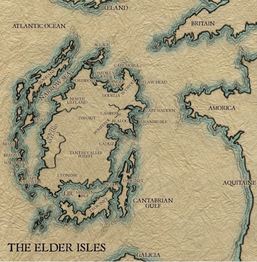

In European legend, both the lands of Lyonesse and Hy Brasil, as well as the city of Ys, sank beneath the sea. In Vance’s novel they are found among the “Elder Isles, now sunk beneath the Atlantic, [which] in olden times were located across the Cantabrian Gulf (now the Bay of Biscay) from Old Gaul.”

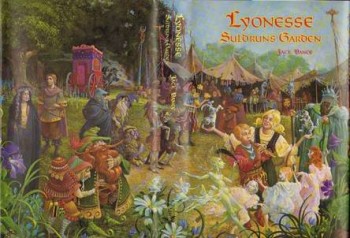

While ostensibly set between the fall of the Roman Empire and the rise of King Arthur, the civilization of the islands is like that found in the Romances of the High Middle Ages, though pagan, not Christian. It is a land of glittering palaces, fairy kingdoms, knights, and evil witches. Kings, lords, and wizards vie for power, the best of them hewing to a code of chivalry. A magic talking mirror, imps, waggish fairy kings, and all sorts of other magical denizens nearly litter the length and breadth of the Elder Isles. All in all, a glorious land for heroes and villains to play out their roles.

Most of L:SG is composed of nearly discrete tales about the ambitions and travails of individual characters. Slowly they become entwined with each other, changing their lives and destinies. Eventually the separate stories come together in a crescendo of action, violence, and even some much needed restoration.

The book opens with the birth of princess Suldrun, daughter of King Casmir and Queen Sollace of Lyonesse. She is immediately neglected by the king because she “had thwarted his royal will by coming female into the world,” and by the queen because the king is displeased.

As a child, she is left in the care of her wet-nurse:

As a child, she is left in the care of her wet-nurse:

Ehirme, untrained in etiquette and not greatly gifted in other ways, had assimilated lore from her Celtic grandfather, which across the seasons and over the years she communicated to Suldrun: tales and fables, the perils of far places, dints against the mischief of fairies, the language of flowers, precautions while walking out at midnight and the avoidance of ghosts, the knowledge of good trees and bad trees.

As she matures, her father begins to see her as a potential bargaining chip and has Suldrun put into the hands of the ladies of the court for a “proper” education.

Suldrun is a restless girl unwilling to be bound by her father’s demands. Seeking refuge from her newly restricted life, she discovers an abandoned garden outside the confines of her father’s castle:

The ravine descended steeply; the ridges to either side assumed the semblance of low irregular cliffs. The path angled this way and that: through stones, clumps of wild thyme, asphodel and thistles and out upon a terrace where the soil lay deep. Two massive oaks, almost filling the ravine, stood sentinel over the ancient garden below, and Suldrun felt like an explorer discovering a new land.

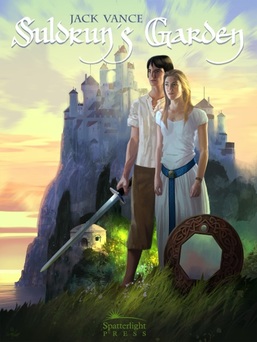

Her new-found asylum will become the focus of her life and fight for independence. Later, on the beach below the garden, she will meet Aillas, nephew of her father’s greatest rival, the king of Troicinet. Aillas and Suldrun fall in love, and she gives birth to a son. Their romance triggers a series of events, told in several distinct storylines, which leaves the political landscape of the Elder Isles changed.

Her new-found asylum will become the focus of her life and fight for independence. Later, on the beach below the garden, she will meet Aillas, nephew of her father’s greatest rival, the king of Troicinet. Aillas and Suldrun fall in love, and she gives birth to a son. Their romance triggers a series of events, told in several distinct storylines, which leaves the political landscape of the Elder Isles changed.

Following Suldrun’s story is that of her father, Casmir. In previous years the Elder Isles were a single realm, but now they have become divided into several kingdoms, as well as enclaves of Celtic invaders and the Ska, a race of arrogant warriors. Casmir dreams of reuniting the lands under his rule, and begins overturning the balance of power that has kept any one ruler from taking control. While offstage for much of the book, the ever-conniving king is always lurking in the background.

One of Casmir’s plans is to marry Suldrun off to Faude Carfilhiot, lord of Vale Evander. Unknown to Casmir, the man with which he hopes to forge an alliance is not a man at all but a creation of the witch Desmëi, and lover of the powerful wizard Tamurello, with his own ambitions and dreams of power. While there are numerous villainous characters, high and low, in Lyonesse, Carfilhiot emerges as the most extravagantly evil, and definitely the most memorable. He moves through scenes with a wicked swagger and an eye constantly turned toward twisting events to his advantage.

An example of his ingenious cruelty, and Vance’s humor at its blackest, is displayed by his treatment of some of the prisoners in his castle, Tintzin Fyral:

Carfilhiot led Sir Glide and his companion up a low flight of steps, past a kind of aviary thirty feet high and fifteen feet in diameter, equipped with perches, nests, feeders and swings. The human denizens of the aviary exemplified Carfilhiot’s whimsy at its most pungent; he had amputated the limbs of several captives, both male and female, and had substituted iron claws and hooks, with which they clung to the perches. Each was adorned with plumage of one sort or another; all twittered, whistled and sang bird-songs.

The next major storyline concerns the adventures of Aillas. He first enters the story as a young and inexperienced agent of his uncle, the king of Troicinet. Following his escape from imprisonment by Casmir, he begins a quest for his son, Dhrun. This quest takes him through all manner of danger, including a lengthy stint of enslavement by the Ska. Unlike many Vance heroes who begin and end as loners, Aillas acquires several boon companions. Along the way he is outwitted by a fairy king and battles a fox-faced witch (several times) and other dastards almost too numerous to count. Aillas’ peripatetic adventures allow Vance the luxury of showing off at least a half dozen mysterious places ruled by strange customs and/or beings.

The next major storyline concerns the adventures of Aillas. He first enters the story as a young and inexperienced agent of his uncle, the king of Troicinet. Following his escape from imprisonment by Casmir, he begins a quest for his son, Dhrun. This quest takes him through all manner of danger, including a lengthy stint of enslavement by the Ska. Unlike many Vance heroes who begin and end as loners, Aillas acquires several boon companions. Along the way he is outwitted by a fairy king and battles a fox-faced witch (several times) and other dastards almost too numerous to count. Aillas’ peripatetic adventures allow Vance the luxury of showing off at least a half dozen mysterious places ruled by strange customs and/or beings.

The last major character is Dhrun. Hidden from Casmir by Suldrun, he is stolen by the fairies of Thripsey Shee and replaced with the changeling Madouc (who will figure in the subsequent two volumes of the series). While only a single year passes in the human world, Dhrun, captive in a fairy realm, ages nine. The fairies deem him too old and human to stay with them any longer and send him off, but not before presenting him with several magical devices. His adventures, ultimately in search of his father, Aillas, lead him to battling a child-eating ogre, gaining the companionship of a young girl, Glyneth, and a job in a travelling medicine show. The latter provides some of the funniest scenes in the book.

For the first half it’s unclear where L:SG is going. Only gradually does the greater story, the struggle for the future of the Elder Isles, come into view. Unknown to the characters, but known to the reader from the very first pages, the Elder Isles are doomed to sink beneath the waves. This aura of doom never becomes prominent, but it lingers in the shadows, never allowing us to forget that all of Casmir’s, Aillas’, and the wizards’ plans will come to nothing in the end.

One of the worst things about much contemporary writing is its inability to separate itself from our current mindset. Our own ancestors a thousand years ago thought about the world in very different ways than we do. Too often stories are written to cater to our modern concerns, and don’t convey the alienness of the past. Characters will react to events like they had stepped right out of today, with the same attitudes about social mores, politics, life, the universe, and everything.

Vance will have none of that, and Lyonesse’s inhabitants adhere to very different standards than our own. As you should when opening a book as fantastic as this, you enter a society ages removed from our own, with far different perceptions and opinions on everything.

Justice, when it comes, is expected to come swiftly as it does when Aillas captures a bandit. There is no time for legal pieties, nor are any expected:

“Time presses. Bode, bind Sir Descandol’s arms and legs, so that he need not perform all manner of graceless postures. We respect his dignity no less than he does ours.”

“That is very good of you,” said Sir Descandol.

“Now then! Bode, Cargus, Garstang! Heave away hard; hoist Sir Descandol high!”

The Ska’s racism toward every single non-Ska makes perfect sense from their perspective, and Vance explicates it in great detail. Witches’ and wizards’ motives remain nearly unknowable and distant from the affairs of men, while fairies act with a childish fickleness. Except in the broadest sense, you will never feel on truly familiar ground in L:SG, which I consider a tremendous plus.

The Ska’s racism toward every single non-Ska makes perfect sense from their perspective, and Vance explicates it in great detail. Witches’ and wizards’ motives remain nearly unknowable and distant from the affairs of men, while fairies act with a childish fickleness. Except in the broadest sense, you will never feel on truly familiar ground in L:SG, which I consider a tremendous plus.

While Vance has an easy way with sardonic humor and pungent whimsy, he could also write with tremendous beauty, and convey the strange wonder of the numinous world that surrounds his characters. While traveling through the wilds, Scharis, one of Aillas’ companions, has heard music no one else can. Aillas wishes he could have heard it as well:

Scharis stared into the fire. At last he spoke, half-musing. “For a fact, I am ordinary enough — if anything, too ordinary. My fault is this: I am easily distracted by quirks and fancies. As you know, I hear inaudible music. Sometimes when I look across the landscape, I glimpse a flicker of motion; when I look in earnest it moves just past the edge of vision. If you were like me, your quest might be delayed or lost and so your question is answered.”

Aillas stirred the fire. “I sometimes have sensations — whims, fancies, whatever you call them — of the same kind. I don’t give them much thought. They’re not so insistent as to cause me concern.”

Scharis laughed humorlessly. “Sometimes I think I am mad. Sometimes I am afraid. There are beauties too large to be borne, unless one is eternal.” He stared into the fire and gave a sudden nod. “Yes, that is the message of the music.”

Vance was one of the most distinctive prose stylists ever. With a vocabulary as varied and strange as Clark Ashton Smith’s, but with greater discretion wielding it, he created some of the very best writing in science fiction and fantasy. If the narrative and characters don’t strike your fancy from the bits I’ve presented, you might still find yourself swept up by Vance’s words alone. You will encounter strange words, archaic words, words twisted to Vance’s own purposes. Some have been meticulously pieced together into lines of glorious irony and others forged into sequences of power and fury. I can can assure you, if you haven’t read him before, you have never read anyone quite like him.

Much of the Vance I have read in the past is concerned more with plot and worldbuilding. Characterization can be considered thin, though never in a way detrimental to the story. Much longer than most of his previous books, L:SG provides the space needed to plumb some of the depths of its assorted heroes and villains. When moments of tragedy strike, they do so with real power because we have come to know Vance’s players so well. Suldrun and Aillas are filled with life and will remain with me, imprinted in my memory, for a very long time.

If you are bored by fantasy that seems like our modern world in D&D drag, where the characters’ morals, perceptions, and attitudes are no different than someone’s from the present day, I implore you to read this book. If you want to enter a world that is like dreams and nightmares, that functions by its own rules and has a nature very different from our own, read this. If you haven’t read Vance but have always been curious, read this.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Swords & Sorcery: A Blog when his muse hits him.

And every time I read something like this, Vance moves closer to the head of my TBR list.

I envy a first time read of Jack Vance.

Well, “to be reread” in this case. I’ve read … most? of his work; the big gaps are the mysteries and the earlier pulp stories. But I have them all waiting.

I think these are some of the most beautiful books I’ve ever read. Books like these are the reason I read fantasy. I’m with Fletcher, envying anyone who’s reading Vance for the first time.

@JoeH – I have a ton left to read – fortunately, I’ve got tons of my dad’s old paperbacks and Spatterlight has made everything available as e-books.

@CMR – If fantasy can’t be as, well, fantastic as these, why bother? Absolutely the sort of book I read this stuff in hopes of finding.

The fact that my Kindle contains the collected works of both Jack Vance and Clark Ashton Smith means that it’s objectively better than other people’s Kindles. I just wish Hippocampus or somebody would do an eBook edition of Smith’s poetry.