The Series Series: Why Do We Do This To Ourselves? I Can Explain!

What’s up with the Big Fat Fantasy books? Books that crest a thousand pages, books that fell forests, books that travel in savage packs of series. We wait three years, five years, ten years for the next volume. Meanwhile, the scope of what the author must remind readers about between installments expands (a storytelling problem anatomized over here by Edward Carmien). We click over to the fan-run online encyclopedia to remind ourselves who the characters are, both because it’s been so long since the last volume, and because the cast size is just that large.

Yet many of us love such books. In my case — and maybe yours, too — not just a few odd specimens of the type, but the type itself.

Thomas Parker laid out all the objections that can be leveled against the sprawl of our genre’s most popular novels, not as an outsider but precisely as an insider shocked at what has become normal to him. (Embrace the tongue-in-cheek hyperbole and just go with it — the main point’s still sincere.)

Someone please tell me. Why? Why do we do this to ourselves, we devotees of science fiction, horror, and (especially) fantasy? What did we do to deserve this? What crime did we commit in some previous existence that we now have to expiate with such bitter tears? Judge, I deserve to know! I demand answers!

If readers are asking themselves that question in that way, even in jest, you can bet the authors are, too, often with a greater level of frustration.

I have to marshal all my hubris to say this in public, but guys, I think I might have the answer. Seriously, not just an answer, but maybe the central answer.

Exploring the answer to this question about bulky stories, of course, will involve a couple of stories and a little bulk. It’ll also involve some claims about the postmodern condition that are guaranteed to inspire some argument — maybe some argument from you, which would be welcome and cool. Please stick with me. I promise I can make my case without resorting to a sequel.

The first time I stuck with writing a novel all the way to The End, the manuscript of the first draft weighed in over an embarrassing 350,000 words. That’s over 1,000 pages. I tried splitting the book, but then it didn’t have a beginning, a middle, and an end anymore. So I wrote it a new middle, and reworked what was now the end to make it feel all ending-y. Pretty soon I was right back up to 300,000 words.

Why did I do this to myself? Publishers aren’t thrilled to receive a manuscript like that from their authors who are already bestsellers, and nobody wants to see such a book from a debut novelist. How do I know? We love your book, say the rejection letters in my files, we dream in your city, but you’re not famous enough to get away with a book this long. Please send us something shorter. Please?

Over the ten years since that first finished novel, I’ve written a lot of other things. But I always struggle with my tendency to write long.

It turns out, it’s not simply a lack of discipline that causes some writers to produce works of troublesome length, and it’s not a failure of discernment that causes readers to keep embracing them.

There’s something a sprawling book can do that a shorter book can’t. Not just can’t do as well, but can’t do at all. And many readers are starving for exactly that thing.

Here’s what I learned from trying to turn my back on that virtue in favor of other virtues.

Word Count Is a Function of Cast Size

My early efforts to write short stories under 7,000 words — the maximum length most magazines will consider — consistently resulted in novellas. I like to think they’re mighty fine novellas, and apparently an award jury agrees, but it’s never easy to find a home for a 25,000 word manuscript. (My Kickstarter campaign to self-publish one that’s very much in the Black Gate mode ends at noon on Thursday the 19th.) Why was it so hard for me to write a story that felt complete and satisfying to me at a length under that threshold?

I found the first big clue in a review by Daniel Handler (who also writes as Lemony Snicket) of a major collection of H.P. Lovecraft’s stories. Whenever I’d tried to read Lovecraft, his purple prose and unbalanced narrators had totally failed for me as horror literature. I could not stop laughing. Call it blasphemy against the canon of fantasy literature, but for me, Lovecraft is only two steps up from “The Eye of Argon” — or maybe zero steps, since I’ve found a great way to use “The Eye of Argon” in my teaching, which I can’t say yet for Lovecraft.

Now, Handler recognizes the problem of unintentional comedy in Lovecraft, but then he turns it completely around to reveal what makes Lovecraft essential:

[P]erhaps 50 pages into this 800-plus page anthology … something begins to shift, and what was supposed to be sublime (but is actually ridiculous) becomes something that was supposed to be ridiculous, but is actually sublime. Part of this is simply getting accustomed to so melodramatic a prose style, but there is also, undeniably, a cumulative emotional weight. One hysterical narrator is off-putting; four is a running gag; but 22 is something else entirely, and over the course of this collection […] Lovecraft’s credo becomes quite clear. Arguably, the oldest and strongest emotion of mankind isn’t fear. The first emotional state, if you consult the Bible, appears to be loneliness. After a day naming the animals, Adam is willing to give up one of his brand-new ribs for a little companionship, and the heroes of Lovecraft stories are similarly bereft. […] If you spend enough time in Lovecraft’s lonely landscapes, fear really does develop: not the fear that you will come across unearthly creatures, but the fear that you will come across little else. And what first seems horridly overdone accumulates a creepy minimalism. Taken as a whole, Lovecraft’s work exhibits a hopeless isolation not unlike that of Samuel Beckett: lonely man after lonely man, wandering aimlessly through a shadowy city or holing up in rural emptiness, pursuing unspeakable secrets or being pursued by secret unspeakables, all to little avail and to no comfort. There is something funny about this — in small doses. But by the end of this collection, one does not hear giggling so much as the echoes of those giggles as they vanish into the ether — lonely, desperate and, yes, very, very scary.

Not only did Handler hand me the key to understanding what makes Lovecraft compelling for so many readers, but he handed me the key to something about my own writing that I hadn’t seen before.

I love an ensemble cast. Reading, writing, watching, whatever. In my imaginative life as in my personal life, I’m an extrovert. The struggles of a main character connect with me best when that main character is part of a community. The solution to the existential horror Lovecraft’s protagonists face had always seemed so obvious to me that I’d never articulated it fully, even to myself. The cosmos as a whole doesn’t prefer you over its other components? Of course not. Unimaginably vast forces that would crack your mind open if you let yourself understand them are destroying your world, and you are entirely beneath their notice? Well, that would explain a lot. So what do you do?

You take comfort in the people you love, you go down swinging in their defense, and you live your mammalian values of compassion and connection intensely, as long as it does any good — and then longer, to the last breath, if only in reproof of whatever in the universe stands opposed to them.

Or maybe that isn’t obvious. But I’m pretty sure it’s not just me.

For whatever reason, Lovecraft was not a person, or an author, who could go there.

But the man could write a shorter story than I could. I’ll go to school on anyone who knows something I don’t, including authors who stretch me beyond the bounds of easy sympathy. What could the thing that appeared to me to be a malady in Lovecraft teach me about the gap in my craftsmanship?

But the man could write a shorter story than I could. I’ll go to school on anyone who knows something I don’t, including authors who stretch me beyond the bounds of easy sympathy. What could the thing that appeared to me to be a malady in Lovecraft teach me about the gap in my craftsmanship?

First, I tried sharpening the distinction between the main character and the secondary characters. Simplifying the supporting cast, making my protagonist the only one who got to be as vivid and three-dimensional as I prefer for every significant character to be, got me out of novella territory. I could get my stories down to about 10,000 words and still feel that my work hit my own sweet spots.

What about getting the count lower? Magazine editors tend to set their cutoffs at 4,000 words or 7,000 words. What kind of cast size can you fit into that length, and what can you do with it?

I really don’t think you can squeeze in much of a supporting cast, unless those secondary characters are functioning more as props than as people. At most, you can have two realized characters, but that second can only be squeezed in if you’ve got serious writing chops. More characters than that, and you’re down to tricks that, as Elizabeth Bear likes to put it, hack the reader’s neurology: one telling detail that leads the reader to do all the work filling in a character around it. Okay, that’s a cool skill, one worth having, especially if you can do it so that the reader forgets s/he did all the work and remembers the story as if you’d written the character s/he filled in for you. I think I’ve pulled that trick off exactly once. Man, that was strenuous, and not in the ways I find exhilarating.

Alternatively, you can embrace the thinness of the secondary characters and make clear to your readers that you’ve piled up the story’s awesomeness in some other dimension of your storytelling. A friend who reads hard science fiction short stories almost exclusively has explained his very different readerly sweet spot, saying, “I usually prefer my characters to be cardboard cutouts, so they don’t get in the way of the wonder.” If that’s what you groove on as a reader, or if that’s the profile of the audience you’re going for, then the problem of keeping your word count down is solved.

(My favorite specimen of this kind of story is Matthew David Surridge’s The Word of Azrael. It achieves a specific form of excellence I don’t anticipate matching, ever.)

Another approach is simply to strip away the wider social world and create a situation that leaves one or two people to work out the story’s conflict in isolation. You can get a lot of tension out of a two-person cast. Put them in a lifeboat or a heap of bodies left for dead, on a cliff face or a one-way mission to deceive the enemy, and those two characters can put on a lively show.

But the one-character story?

It’s possible, of course. Some of you are watching your brains formulate a list of greats and classics of just this kind at this very moment, and I would love to hear about them in comments. Maybe someday a story like that will come to me and demand that I be its author. So far, though, a character isolated enough to finish her business in 4,000 words is missing out on almost everything that engages me as a reader or writer of fiction.

As Don DeLillo, a giant of mainstream postmodern literary fiction, observed in an NPR interview, writing about characters in sufficiently isolated and solitary conditions to result in short stories will lead inevitably to writing about isolation and solitude as themes.

There’s room for that, of course. There’s room for every kind of awesome.

But I argue that we’re in a cultural moment — or more likely a cultural era — that calls for something else. Something specific.

Our Familiar Terms Fail Us

One fun thing about author interviews is that, sometimes when I’m figuring out a response to somebody else’s question, I’ll accidentally answer one of my own. Iulian Ionescu of Fantasy Scroll interviewed me for the February issue, and while I explained the weird way my childhood exposure to Shinto in Japan resulted in my writing about Wiccan characters in New Jersey, this observation came out:

If I had to guess why so many fantasy readers tend to love sprawling multi-volume epics, I would say they want community-of-characters-driven stories, not just character-driven ones.

I now think the gap between the terms we use and the thing we’re trying to talk about is even wider than that, but I’ll come back to the gap later. I want to start with that familiar term, character-driven, and take it apart a bit first

Go to any SF/F convention to the inevitable panel on what editors and agents are looking for, and you will hear the speakers hold forth on character-driven fiction. Google the term, and you’ll find it’s all over the how-to-write-a-novel sites, good and bad.

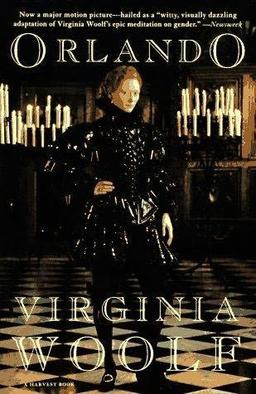

No matter who you find speaking on the subject, they’re in the tradition of Virginia Woolf, whether they know it or not.

Once upon a time in 1923, an edgy countercultural writer with a penchant for self-publishing gave a talk to a college students’ club called the Heretics. “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown” is probably the most important essay exploring character in fiction to come out of the 20th century, or perhaps any century. Oh, but we are a lucky posterity, because that talk is still available to us. It’s a wonderful essay particularly for readers of speculative fiction who want to think seriously about our genre as literature: here we see Woolf, whose Orlando makes far more sense as SF/F than as mainstream literary fiction, explaining with great sympathy why H.G. Wells falls short for her as a model. Every writer of fiction, in any genre, would be able to find something of use here. And it’s fun to read, just plain fun.

It seems possible to me, perhaps desirable, that I may be the only person in this room who has committed the folly of writing, trying to write, of failing to write a novel. And when I asked myself, as your invitation to speak to you about modern fiction made me ask myself, what demon whispered in my ear and urged me to my doom, a little figure rose before me — the figure of a man, or of a woman, who said, “My name is Brown. Catch me if you can.”

The drive to create fiction is, for Woolf, the drive to capture character, not only as a matter of her personal experience, but as a matter of aesthetic necessity.

The drive to create fiction is, for Woolf, the drive to capture character, not only as a matter of her personal experience, but as a matter of aesthetic necessity.

Although Woolf claims not to have captured her Mrs. Brown, the scene she gives us of overhearing a conversation on a train is so delicious that I will leave it as a surprise treat for you. By the end of that dialogue, you will be as ready as Woolf was, or I was, to imagine a dozen wildly different novels about that enigmatic lady. A writer’s struggle, Woolf explains, is the struggle to imagine an inner life for her characters, and make that inner life live, and then to make her readers feel that aliveness. The struggle was particularly challenging for writers of Woolf’s generation, who experienced their forefathers’ tools as not just inadequate but deadly. She sets her scene again, with the three foremost authors of the generation before her riding in the railway carriage along with the mysterious Mrs. Brown.

Plenty of writers publishing right now suffer from greater or lesser versions of the problems Woolf shows us in her Edwardian heavy-hitters. We won’t all come up with the same 21st century analogues, but I’m sure you’ll think immediately of current SF/F writers who have quirks like these. And the authors who didn’t make it out of the slush pile often have the same problems, only writ much, much larger.

So, what are the artistic hazards of fiction that is not character driven? It can refuse to engage the messiness and particularity of lived human experience in favor of ideals that exclude not only Mrs. Brown, but all of us as we actually are:

Perhaps we can make this clearer if we take the liberty of imagining a little party in the railway carriage — Mr. Wells, Mr. Galsworthy, Mr. Bennett are traveling to Waterloo with Mrs. Brown. Mrs. Brown, I have said, was poorly dressed and very small. She had an anxious, harassed look. I doubt whether she was what you call an educated woman. Seizing upon all these symptoms of the unsatisfactory condition of our primary schools with a rapidity to which I can do no justice, Mr. Wells would instantly project upon the windowpane a vision of a better, breezier, jollier, happier, more adventurous and gallant world, where these musty railway carriages and fusty old women do not exist; where miraculous barges bring tropical fruit to Camberwell by eight o’clock in the morning; where there are public nurseries, fountains, dining-rooms, drawing-rooms, and marriages; where every citizen is generous and candid, manly and magnificent, and rather like Mr. Wells himself. But nobody is in the least like Mrs. Brown. There are no Mrs. Browns in Utopia. Indeed, I do not think Mr. Wells, in his passion to make her what she ought to be, would waste a thought upon her as she is.

Partisans of H.G. Wells, hold off a moment, because here Woolf comes with another author, John Galsworthy, whose character-writing problems are entirely different. He’s so interested in advocating social change that he’s lost sight of the people he wants to change as having unique dignity or value as they are right now:

And what would Mr. Galsworthy see? Can we doubt that the walls of Doulton’s factory [through the carriage window] would take his fancy? There are women in that factory who make twenty-five dozen earthenware pots every day. There are mothers in the Mile End Road who depend upon the farthings those women earn. But there are employers in Surrey who are even now smoking rich cigars while the nightingale sings. Burning with indignation, stuffed with information, arraigning civilisation, Mr. Galsworthy would only see in Mrs. Brown a pot broken and thrown into the corner.

For the third author Woolf imagines in the carriage, Arnold Bennett, we in SF/F have some terms and tools to name the problem she diagnoses. She quotes at length from one of Bennett’s novels to show how he introduces character. In Hilda Lessways, instead of welcoming the reader into the heroine’s inner life, he tries to establish her character by describing all the objects she owns, and the landscape around her, right down to the price of real estate as it applies to every last building she can see through her window. Woolf concludes:

For the third author Woolf imagines in the carriage, Arnold Bennett, we in SF/F have some terms and tools to name the problem she diagnoses. She quotes at length from one of Bennett’s novels to show how he introduces character. In Hilda Lessways, instead of welcoming the reader into the heroine’s inner life, he tries to establish her character by describing all the objects she owns, and the landscape around her, right down to the price of real estate as it applies to every last building she can see through her window. Woolf concludes:

One line of insight would have done more than all those lines of description; but let them pass as the necessary drudgery of the novelist. And now — where is Hilda? Alas. Hilda is still looking out of the window. Passionate and dissatisfied as she was, the girl had an eye for houses. She often compared […] Mr. Skellorn with the villas she saw from her bedroom window. Therefore the villas must be described. […] Heaven be praised, we cry! At last we are coming to Hilda herself. But not so fast. Hilda may have been this, that, and the other; but Hilda not only looked at houses, and thought about houses; she also lived in a house. And what sort of house did Hilda live in?

And then Bennett describes it. And describes it. And…

If you ever thought Tolkien spent too many sentences on landscapes his characters walked through, you ain’t seen nothing yet.

Using terms and diagnoses common in SF/F, we might say Bennett tried to make his worldbuilding do the job of characterization, rather than use both sets of techniques to inform one another. As with Wells and Galsworthy, whom Woolf praises as human beings, she takes pains to note what she admires about Bennett the man before naming the flaw in his craftsmanship that vexes her most.

[H]e is trying to make us imagine for him; he is trying to hypnotise us into the belief that, because he has made a house, there must be a person living there. With all his powers of observation, which are marvellous, with all his sympathy and humanity, which are great, Mr. Bennett has never once looked at Mrs. Brown in her corner. There she sits in the corner of the carriage — that carriage which is travelling, not from Richmond to Waterloo, but from one age of English literature to the next, for Mrs. Brown is eternal, Mrs. Brown is human nature, Mrs. Brown changes only on the surface, it is the novelists who get in and out — there she sits, and not one of the Edwardian writers has so much as looked at her.

What does that have to do with us here in SF/F?

The slushpiles of our science fiction and fantasy are full of inventive ideas and settings, fast-paced action scenes, and plots in which things actually happen, but unless there’s at least one vivid character in there somewhere, a story is unlikely to find a market or a reading constituency. Google around, it’s easy enough to find discussions by most major figures you’d want to hear from on the subject. Rather than search out the most eloquent explanation out of hundreds, I’m going to boil it down to the bluntest, which happens to be from David Gerrold:

[W]hat I learned about writing as well as science fiction is that the real challenge is not the story, but the human telling the story. What are we discovering about ourselves in these strange new worlds. Because after a while flying in spaceships, battling aliens, traveling through time, [bleep]ing a sexbot, whatever the story is about, is boring if we don’t also discover something exciting about what it means to be a human being.

There are other ways of seeing the matter, but I think we can agree this is a view many people hold. The kind of discovery Gerrold’s talking about, of course, gets harder to develop in a short story manuscript the shorter the story aims to be.

Seriously, it’s easier to pull off in a three-line lyric poem, which can do the job by alchemizing an image and some soundplay into an implication, than to pull off in a 1,000-word short story, which requires at minimum a character, a situation, a problem, and a change.

Why Isn’t It Enough to Call a Large-Cast Piece Character-Driven?

Many of the things that make us human are social in origin — our big brains developed because living in family and community groups is complicated. If you want to explore the full range of human character, sooner or later you have to explore it by throwing characters together.

You could continue to use the term character-driven to talk about stories with ensemble casts, but I think it’s useful here to make a distinction between stories that examine the development of a character in the context of his or her community, and stories that examine the development or transformation of a community dynamic among characters (even if one character gets more stage time than the others). Whether the group of characters is a family, a team of mercenaries, a lifeboat full of random shipwreck survivors, a coven of ordinary Pagans on a supernatural version of the Jersey Shore, or Buffy the Vampire Slayer and her Scoobies, a community dynamic story offers a reader different pleasures from those of a character-driven story with a tighter focus, and makes different demands.

Certainly it demands that the writer think differently about structure, pacing, exposition, viewpoint… not quite everything, but an awful lot of somethings. You can fit a community-driven story into a novella with a little breathing room to spare, and into a novel with plenty of space left over for all your characters to do yoga, if you adjust all of the story’s other parameters around the assumption of a large cast.

As for the reader, even if the community dynamic story doesn’t require retaining and recalling a mass of details, it usually rewards readers who do with little bursts of extra surprise, delight, and puzzle-solving gratification.

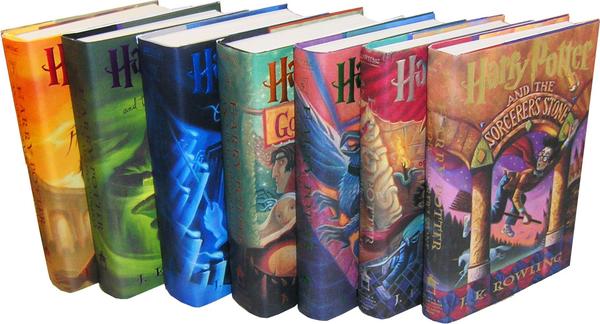

I’ve been asking myself if it’s possible to write a community-dynamic-driven story from a single character’s viewpoint, and actually, I think it is. Consider Harry Potter. For the first few books of Rowling’s series, Harry himself is one of the least vivid characters — what makes those early volumes tick is the dual process of his finding his place in the wizarding world and the wizarding world’s coming to terms with his return after a childhood in hiding. That dual process never entirely ends, though other threads of story take precedence later. The wizarding world at times functions as a unified character-like entity, at times as a bundle of conflicting factions, and at times as a fractally complex ecosystem of individuals, every named one of whom has a story that J.K. Rowling cares about. If you want to keep track of her characters who, at first occurrence, seem likely to be walking props with throw-away names added for verisimilitude (which is what they’d be in books that weren’t driven by community dynamics), your attention will always be repaid.

People asked, and still ask, why the Harry Potter books got so long. It’s the obvious question to ask. Was it self-indulgence enabled by poor editing? Pandering to an audience that could be counted on to clamor for more, no matter what? Surely Harry’s story could have been told in fewer words.

And it could have, but that would have missed the point. Harry’s a nexus for what’s going on in his social world, and that’s what Rowling and many of her readers showed up for.

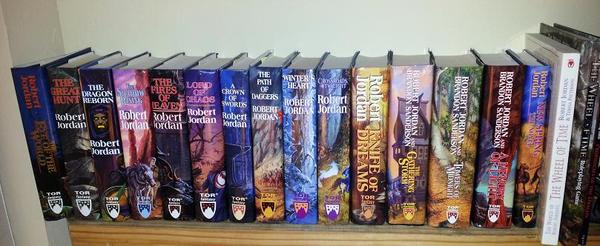

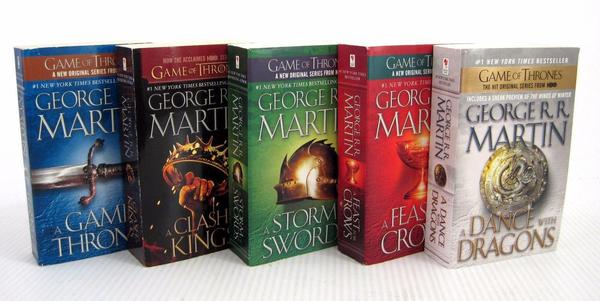

Having a term to distinguish community-driven stories from (single) character-driven ones is especially useful when we want to talk about books and series that use serial third person limited point of view. Each chapter of the Song of Ice and Fire books has a central character whose perspective defines what kinds of sensory vividness, actions, and interiority can go on those pages, but when the chapter ends and a new character’s viewpoint becomes the reader’s lens, George R.R. Martin commits just as absolutely to that next character. Some characters get chapters despite being minor characters, or being characters of major importance who will not themselves be central protagonists. (Arys Oakheart, anyone?) But for the most part, Martin doesn’t use the serial third person viewpoint just for the convenience of revealing information to the reader in a part of his world where none of his major characters are there to see it.

It’s not an accident that we can’t reduce the story to one about Jon Snow, or Daenerys Targaryen, or Arya Stark, or Tyrion Lannister. It’s part of the point. This is the story of the people of Westeros — a story bigger than the continent of Westeros itself — and how their whole social ecosystem transforms under a confluence of pressures from within and without. Quibble if you like with Martin’s creative decisions and his editor’s restraint, say his purpose is to your taste or not, but his scope is undeniably purposeful.

Is It Enough to Call a Novel Community-Driven When It Sprawls across Two Continents, Seven Kingdoms, Three Collapsed Empires, a Passel of Free Cities, and Two Migrating Anarchic Proto-Nations?

Nope.

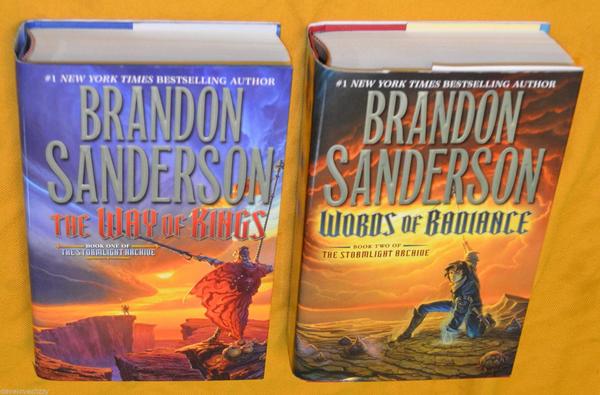

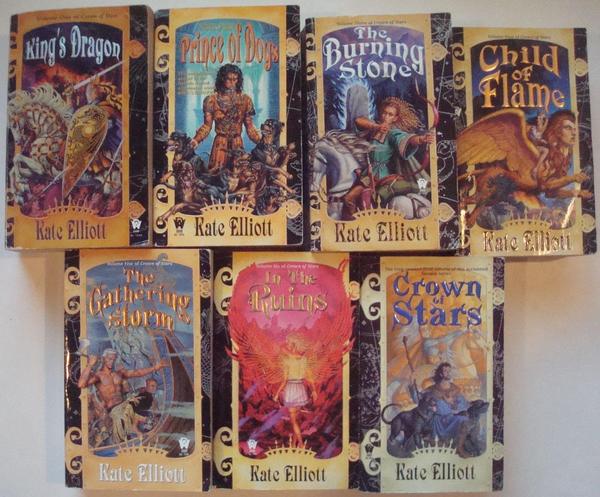

“Community-driven” comes closer than “character-driven” when it comes to describing massive multi-volume fantasy epics like Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire, Brandon Sanderson’s The Stormlight Archives, or Kate Elliott’s The Crown of Stars. Still, that doesn’t quite do the job.

We’re going to need a bigger term.

Because what’s going on in those series, and others on that kind of scale, is about communities of communities. (It’s tempting to used the familiar term “community of nations,” just to avoid repetition, but nationhood isn’t always the social structure in play.) A community of communities will — inevitably, even in the best of times — have conflicts, unstable alliances, coalitions around single issues among otherwise opposing factions. Sometimes they will have unification or schism, war or reconciliation.

Individual characters can drive, and be driven by, all of those dynamics.

There are plenty of character-driven books, or even short stories, that use such large-scale dynamics as background for the journey of a single character. That can be done at the highest level of excellence. There are community-driven books that use them as backgrounds for the collective journey of a family or a family-like group. Some of those books are perfect specimens of themselves, too.

I want to make clear that I’m not arguing for the superiority of any one form, scale, style, or taste over any other. Remember the friend I mentioned earlier who favors hard science fiction short stories of about 4,000 words with thin characters so they don’t get in the way of the ideas? He’s one of the smartest people I’ve ever known, and at times he’s been my go-to beta reader even for my sprawliest manuscripts.

What I’m after here is a way of looking at what’s going on with a form that intermittently baffles our whole community of readers, writers, and publishing industry professionals — even while we’re creating and consuming books in that form.

One of the reasons I’ve heard people propose for why we’re seeing so many epic series now is that the software we use for word processing, and for the whole environment in which we use that software, allows us to keep track of longer manuscripts with more stuff in them. I think that probably is one cause for the weird, overdetermined phenomenon of the mega-epic.

It seems to me, though, that one reason this extreme of long-form fiction is having its moment now is that, whether we like it or not, globalization drags all of us into a multi-cultural world. Even if our neighborhoods, towns, or families are still homogeneous, we live with the consequences of actions taken by other people living very different lives all over the world, and those others have to live with the consequences of ours.

And many of us live in neighborhoods, towns, or families that are already mixed.

At my in-laws’ Thanksgiving table, I’ll be part of a huge family that has maintained its Thanksgiving traditions for eighty years and four generations. It’s also a family whose various branches include people from four ethnicities, three nations, and at least six distinct religious identities. Thinking multiculturally is optional for some people, but it’s not really optional for us. It has to be one of our family values, because we value our family as it is, and everyone in it as they are.

The sprawling multi-volume epic, especially in the speculative genres, is a literary form that invites us to play with issues like these. Stories can also help us work out ideas, or engage in imaginative rehearsals for kinds of situations we may face in real life, of course. But one of the reasons we love stories is for the many forms of pleasure we can find in them.

We get the chance to play with globalization, to play with intercultural contact, to play with the struggle of a worldful of people to find a way to live in the same world without ending it.

The two things fiction can do that are the most important to me are that it can lift us out of the unbearable and give us respite somewhere else, and it can help us get to the core of hard things we’re dealing with by a slantwise path at times when a direct path would be overwhelming.

Some of the hard things we have to deal with in our times are on a scale that our ancestors just didn’t have to think on. The information technologies of their times didn’t make it possible, let alone inevitable, for them to confront global issues in such detail as we’re awash in.

That’s why we do it to ourselves, why we slog, and await the next volume for as long as it takes, and wade through the fan wiki for the details we’ve forgotten. Because no other art form can balance the extreme interiority and intimacy of fiction that has well-crafted characters with the extreme vastness of the worlds in which those characters and all their contradictory affiliations take their being. No other form can mirror back to us so well our experience of living in a universe that dwarfs us utterly, even as the people we care about most form worlds within worlds that our actions and theirs can save or imperil.

So we have developed a body of fiction on the scales of our predicaments. We are free to avail ourselves of it if we want to, and we’re free to create more of it out of our individual perspectives if we want to. Or not, if we don’t. This is an excellent state of affairs.

Crazy-making, yes. And still excellent.

Sarah Avery’s last post for us was Kickstarting a Belated Black Gate Story: The Imlen Bastard, about her Kickstarter campaign that will end this Thursday, November 19th, at noon. She won the 2015 Mythopoeic Fantasy Award for her novella collection, Tales from Rugosa Coven. The Trafficking in Magic, Magicking in Traffic anthology she coedited with David Sklar includes stories by James Enge, Elizabeth Bear, and Darrell Schweitzer. Her own short stories have appeared Jim Baen’s Universe, Fantasy Scroll Magazine, and the last print issue of Black Gate. Sarah’s an escaped academic who survived earning a Ph.D. in English literature, and an ambivalently entrepreneurial private tutor. You can keep up with her at her website, sarahavery.com and follow her on Twitter.

This post was like a short story that turned into a novella.

🙂

More like a novel that got pruned way back. There was a whole long movement on cognitive science, working memory, and informational chunking that I cut out. Maybe it’ll go into a future post, maybe not.

Whew! One of the longer posts I have read here…

I still believe the word count of many books, not just fantasy, is industry-driven. It’s what consumer’s want, and expect. If there was a demand for 150 page novels, the shelves would be full of them. But no, readers want more for their reading dollar, and publishers are willing to provide it to us. Big, fat, epic novels have always been around. Now they are the norm, and in some cases at the expense of good storytelling… The Broken Sword vs The Lord of the Rings-I know which one I would rather re-read. Of course, how could millions of readers be wrong?

Darkman, I agree that market forces are part of the reason such long books and series are more common now. Yes, there is more demand. What I’m more interested in is what moves readers to form that demand.

Before the revolution in self-publishing, it made sense to ascribe the demand to readers doing a mental calculation of dollars to hours of entertainment. Now that huge swaths of fiction can be found as self-published ebooks, and it’s increasingly possible to find solidly crafted work in that form, why are readers still forking over the bucks at all for traditionally published big fat fantasies?

I don’t think we have to put The Broken Sword in competition with The Lord of the Rings, or with any other work. There’s room for every kind of awesome.

In a post like this, I’m starting with a question that basically comes down to, “What does this button do?”

You might be interested in Fantasy Faction’s list of big fat fantasies by word count. Some of them surprised me.

I thought you had forgotten, Sarah. It can be a dangerous thing to pose a question that someone actually takes seriously!

You are right Sarah, I am trying to answer a question you really didn’t ask. I was born in 1965, the middle of the pulp re-print boom, and was influenced as a young reader in the 70’s as the boom faded.I read Burroughs, Howard, Doc Savage, Horseclans and an endless supply of “Men’s Adventure series” pulp paperbacks. I was the right age for Tolkien, and that upstart young writer Terry Brooks-but it didn’t grab me. And I think it was because I wasn’t a gamer. D&D was huge, and I was not into it. D&D and the like gave fantasy fans a deep, sprawling, multi-player(character) experience that went on and on for many sessions. New fantasy readers wanted the same from their reading experience. And LOTR gave them that, and Sahnnara and Thomas Covenant ect. And so the sprawling, epic, door-stopper, multi-volume fantasy was born. And readers were happy. Most of them…

Just my two cents. I could be totally wrong. Hell, I usually am…

Thomas, not so dangerous, it turns out. Behold, a friendly Darkman.

One of the things I learned from working as a field interviewer for anthrolopologists was this aphorism: You can’t learn something unexpected from a person you’re in the act of judging. I find it’s good to apply to books, too. Sometimes there’s good reason to pass judgment, but I try to separate that moment from the moments when I’m trying to figure out what a thing is and how it works.

Darkman, I’m of that Gen X vintage that was a little young when Shannara came out, and LOTR was already a classic by the time I was ready to process it. Dune had graduated from the Chilton manual publisher to mainstream success. Big fat fantasies have been part of my reading landscape since before my personal golden age of SF/F.

How were the Horseclans books? They were sort fading in popularity before I got into them.

I also had a lot of my formative reading in the 70s & 80s and consumed more than my share of Burroughs and Moorcock reprints, but LotR was my first & last love; and I read (or reread) more than my share of Donaldson and Dragonlance back in the day.

I read the first, um, some number of Jordans and just kind of lost momentum when it became obvious that he was just writing The Two Towers over and over and over again. I read the first three Martin more or less as they were being published, and really enjoyed them, but haven’t gotten around to the later volumes yet. And when I discovered Erikson, I blew through the first five Malazan books (all that were available at the time) in fairly short order, but, again, haven’t gone on to the others.

These days it’s not that I _oppose_ really long series, but it’s hard to commit to something like that; I just spent about three weeks reading Orlando Furioso (and English translation, of course) and I think that’s the longest I’ve spent on a single book in several years.

As for Horseclans, I read & enjoyed a bunch of them back in the day, but looking back I expect that they were extremely problematic …

Bloated series are one of my biggest literary pet peeves. I bought Eye of the World when it was first published, waited, then another, came out, so I decided to wait for the trilogy to be finished. HA! 20 year later I’ve not read any of them. My tastes have changed, I have a career, less time, I’ve had a kid, and she enrolled in college!!…all in the span of time it took to tell a story.

Sorry, but that’s ridiculous. I’ve not fallen in that same trap since, including Song of Fire and Ice.

Is this what fandom wants…or expects? Let me put it this way: Which is easier to write? A thousand page book of mediocre quality, or a brilliant 200 page book? I believe we are subjected to what the publishing world has to work with, a deluge of writers, producing questionably quality work disguised as “epic series.”

Finding standalone SFF today is nigh impossible. I find myself going back in time and looking for older works to read, and ignoring Volume 6 of the Epic New Fantasy Series of the Year!!

I’m currently rereading (for the umpteenth time) the Wheel of time series. I’ve also had multiple rereads of A Song of Ice and Fire, The Belgariad, Lord of the Rings, some of the Shannara novels, and many other massive fantasy sagas. My own theory of why such books appeal to both readers and writers, is this: the thing that separates fantasy, science fiction and horror from all other literature is that something in the background of the story is something that is not part of either the real world of here and now or the real world of any existing historical era. Sometime, that artificial background consists of an entire world with a history and a population of characters roaming around it. Such worlds create a totally immersive experience, essentially forming a sort of escape valve where we can temporarily leave the real world and bring our imagination into Middle Earth, or Westeros or whichever other imaginary world we are reading about.

Long-form fiction has been in ascendance for perhaps as long as like what? Don Quixote? (a book I started but never finished. Talk about an ever recurring scene. It was like a nightmare version of Groundhog Day). When I was in college back in the 90s my first creative writing instructor asked us what our favorite books were. We went round the room stating our favorite books. When we finished he pointed out that not a single person had said a book of short stories (yes, this was a short story class). I became obsessed with Raymond Carver around this time, not just reading about every story he wrote but also interviews and a biography I think. I remember Carver was asked why he hadn’t written a novel and he said when he sat down to write, he didn’t plan on writing a short story or a novel. They just turned out that way and so far, nothing reached novel length.

Sarah, you were going to include some info on cognitive psychology in your post. Maybe I’ll offer my own cognitive explanation (I play a cognitive psychologist to hundreds of students every semester). The book as a unit or chunk has become our expectation for writing of significance (it’s true too for nonfiction). It’s no different in film (name a short you’ve watched recently).

In SF/F we’ve just taken that a step further. The writing of significance is the series, more specifically the trilogy (talk about a trope). While it happens in Literature (Richard Ford’s Frank Bascombe books are a good example), it’s more prevalent in SF/F. I think part of the issue has to do with fandom. Writers are pseudo-celebrities that attract the same level of nerdy obsession that you see with Trekkies. A series feeds that nerdy obsession so that you can remain mired in that cloistered world, regardless of how multicultural the writer has intended their worldbuilding to be (one person can only give so much perspective).

I say all this as an unapologetic fan of Martin’s Song of Ice and Fire Series, but I also love, love, love short stories. Have been since I discovered Carver and SF/F is no different (as a kid I became a reader because of SF/F–what did I read first? The original Dragonlance Chronicles. From there I branched out including subscribing for a time to Asimov’s SFF Magazine. So I read and enjoyed short stories then). I appreciate short stories even more now. And that’s in part because of pragmatic reasons. I work too much and there is nothing I can do to seriously curtail that as a professional in a dual-career (wife is also a professor) relationship. I can read a short-story in a night. A little world that unfolds for me, encapsulated in a brief glimmer of a character’s life, in time to be replayed in my just-drifting-off sleep-thought before I slumber away the day’s anxieties.

[…] Sarah Avery delves into some reasons for the success of multi-volume fantasy in “The Series Series: Why Do We Do This To Ourselves? I Can Explain!” at Black Gate. It’s a really good article but not easy to excerpt because it is (unsurprisingly!) […]

@JoeH – I wrote a review of Orlando Furioso for BG a while back: https://www.blackgate.com/2014/09/25/vintage-treasures-orlando-furioso-the-first-big-fat-fantasy-ever/

Sarah – I think this is a spectacularly useful article. It’s like the wave/particle thing – you’ve reconciled big background plot with character plot. Stories about wars become stories about characters in communities that are part of communities, with conflict at and between each level.

I think the answer to this issue is the sequential series instead of the traditional continous series. Most big fantasy series are really a single big story that can’t be printed in a single volume, but the plot is not really resolved by the end of each book. I don’t really read those stories. Lord of the Rings is as far as I am willing to go.

If you want to have lots of characters and explore many parts of the world and their culture, you can instead have lots of smaller stories that all have their own protagonist and resolution, all set in the same world. And you can even have a character have a second adventure after the first one is wrapped up. Or a third. You don’t have to cram a characters entire life story into a single story.

This format was actually quite common in the past. Howard, Leiber, and Moorcock all used it. An interesting more recent example is The Last Wish by Andrzej Sapkowski.

@M Harold Page — You did! And I commented on it! And I’m glad I finally got around to reading Orlando Furioso — it was long but rewarding.

It’s SF, not fantasy, but I distinctly remember when C.J. Cherryh started publishing her Chanur trilogy — she explicitly said she wanted to tell a single story that was too long for a traditional book, so it had to be broken into three pieces for marketing reasons.

And Dumas was writing some pretty gigantic multi-volume stories back in the day — even prefiguring current trends in the way that the third Musketeers installment itself had to be split into three separate volumes for publication.

But didn’t those start life as serials?

I understand the appeal of continuing stories with continuing characters, but I’ve never been pulled in to any big fat fantasy series. I always thought even the Lord of the Rings needed some trimming. In ALMOST every instance I’ve read, long series succumb to incredible bloat and boring sections that would have been pared out with a disciplined editor or writer in charge remain. It’s as though many modern writers have never had to learn to trim down their prose to get to the point. I think that we really lost something when the market for 60k word novels died.

But then readers apparently like that sort of wandering thing or they wouldn’t keep buying it. Like The Darkman, I was born in the 60s, and I grew up on reprints of Burroughs and Robert E. Howard and Fritz Leiber. Continuing adventures, aye, but not endless and bloated.

I’m yet another 60s-born man who grew up with slim yellow-spined DAW books as a staple of my reading. When a book crosses the three-fifty page mark I start to get a little antsy.

Now, I have read plenty of big, fat books and enjoyed them but I’m in complete agreement with Howard here. Even the best of them succumb to bloat.

I liked about 5/8ths of Tad Williams’ Memory, etc. trilogy. But, oh the other 3/8ths. Endless digressions and minor players that only served to distract me from the greater (and better) story at hand.

I totally get the desire to create a whole world and the desire to immerse one’s self in someone’s creation. I just haven’t found many books that do it well enough to warrant the weight and the wait for the next volume).

As to CJ Cherryh, it was Cyteen that they would only publish as a trilogy. Added up, all three volumes come in just under a thousand pages. How many books push that limit today?

Tron, Darkman, and Howard, you guys have two shared points that make sense to me. Editing is even more important with a very long manuscript, and the very human temptation to resist editing can be even more disastrous with a long book.

And it is a loss, to our genres in particular and to literature generally, that shorter novels have fallen out of favor. I’m hoping that publishing experiments like Tor.com’s novella line can help revive the market for fiction in the length ranges we’ve sort of lost.

Finally, Sturgeon’s law applies in epic series as in other forms. Are 95% of sprawling books crap? Not surprising, if you allow that 95% of everything is crap. There are series I won’t advocate for (though I won’t say here which those are).

And I’m a dope. I forgot to say, Sarah, this is great. It’s the most cogent argument I’ve come across about this. What you’re saying make much sense. In the end it comes down to whether a reader has a taste for such books or not.

Amy, I agree that the immersive reading experience is, at least for me, especially immersive with longer books. And I think even virtual reality and videogame projects that aim to be immersive probably won’t diminish the appetite readers like us have for immersive books. Part of the pleasure of reading in those worlds is doing the mental work for ourselves of turning the words into our own virtual reality.

NOLAbert, I ended up taking the cognitive science bits out and saving them for another post. At the risk of going back on my assurance that I wouldn’t need a sequel, I concluded that it just didn’t feel like part of the same piece.

I do look forward to your thoughts when eventually that one comes together. I’m still definitely planning on writing it.

For me, the short form that balances out my love for sprawly novels is lyric poetry. Extremes of compression and discipline make for totally different beauties. When I read shorter short stories that really work for me, it tends to be because they engage my poetry reading protocols.

I totally get how real life human connections can make some kinds of reading hard to do. There were kinds of books I could read when my kids were babies and kinds I couldn’t. Now that they’re older, my husband and I can read big fat fantasies again mainly because we form a book club of two, and talking about them gets subsumed into the fun side of relationship maintenance.

I have two Martins in the same comment thread, with a third Martin as everyone’s favorite example. No wonder I’m having to scroll back up so much!

M. Harold Page, you’ve hit on exactly the aspect of the issue I was tackling with (a layperson’s understanding of) cognitive science in the passages I cut and saved for a future post. I wanted so much to talk about the microcosm/macrocosm structural similarities. The post just got to be too sprawly, even for me. Next time.

Martin Kallies, the non-sequential self-contained short novels about recurring characters that you’re talking about are actually pretty similar to what I’m doing with my Rugosa Coven novellas. Since those pieces are contemporary fantasy, I hadn’t thought of them in the context of Howard, Leiber, and Moorcock. (Though I did throw the word “scintillant,” one of REH’s favorite adjectives, into one of the novellas, thinking about how much it would amuse Howard Andrew Jones if he ever read it.) I guess those guys had more of a lasting effect on me than I realized.

Joe H., the trilogy is actually older and more mainstream in its roots than most genre readers realize.

Dickens and his contemporaries had to live with a market reality they called “the tyranny of the triple-decker.” Because printing and binding were so costly, and there were so many more people who could pay something to read fiction than could pay enough to purchase books outright, there was an explosion of private lending library clubs. The way those clubs kept enough volumes in circulation to satisfy their membership was by demanding that publishers break novels into three volumes, bound separately. That way three paying members could work their way through a novel semi-simultaneously. Of course, those readers wanted to linger in each of the three sections, so the novels tended toward the bloat that is Dickens’s most famous flaw.

People who don’t have to think too concretely about how else authors might make a living like to quip about how Dickens and his contemporaries were paid by the word, with the implication being that the sprawl is a symptom of greed. I don’t think it’s that simple.

His readers had far fewer forms of entertainment competing for their attention, and if they were getting their books from a lending library instead of buying them, those readers may not have been able to afford a lot of the other entertainments.

The people complaining about the tyranny of the triple-decker in the 19th century were, as far as I know, writers, not readers.

(Anybody who’s a 19th century or Brit Lit specialist is enthusiastically invited to set me straight if I got any of that wrong.)

Fletcher, thanks so much for your kind words.

Differences in taste, and changes in taste and perspective over a lifetime, are good things. There’s a reason my friend who prefers very short hard sf can tell me things about my own work that I don’t see.

I know that my inability to be scared by Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith is my loss, not theirs. For that matter, my inability to connect with romance novels means there’s a handful of writers at the very top of that genre who know things about writing I don’t, and I’ll probably never learn the specific things those masters could teach me.

Every form has its masters and masterpieces, and no one reader can connect with them all.

Fletcher — Cyteen was published as a single volume in hardcover, but had to be split into a trilogy for mass-market paperback release (which Cherryh was not happy with, and said she’d never allow it to be split like that again). The Chanur books (Chanur’s Venture, Kif Strike Back and Chanur’s Homecoming) were conceived of and published as a trilogy that told a story too large for a single book — there’s an author’s note in the back of Kif Strike Back that explains the situation.

(Having said that, I’m guessing that the entire Chanur trilogy has a lower word count than some of the individual volumes in Malazan or some of the other contemporary gigantic-tome series.)

That’s one potentially nice thing about eBook publishing — there’s no longer any physical limitations, so the book can be as long, or as short, as it needs to be for the story it’s telling.

I didn’t know that, Joe. Thinking back on the Chanur books (possibly my favorite sci-fi), that should have been completely obvious.

It’s been far, far too long since I last reread Chanur myself. And now that they _finally_ released Chanur’s Homecoming on Kindle …

@Sarah—just wanted you to know that I liked the article. World building must be an art unto itself. I’m trying my hand at Nanowrimo for kicks just to see if I can do it and I got kinda busy.

Wild Ape, Nanowrimo is one of those things I enjoyed about my life before kids that I’m thinking I can do again in maybe another year or two. Hope you’re having a good November!

[…] At Black Gate, Sarah Avery looks at why we love enormous fantasy book series. […]

[…] Avery has a long and fascinating essay at Black Gate about serial novels and why. It’s one of those essays that I hope will become a […]