The Woman Who Was a Man Who Was a Woman: Alice Sheldon and James Tiptree Jr.

Alice Hastings Bradley Davey Sheldon was a remarkable person — world traveler, painter, sportswoman, CIA analyst, PhD in experimental psychology… and one of the greatest of all science fiction writers. If you don’t recognize her name, that’s partly by her own design.

Alice Hastings Bradley Davey Sheldon was a remarkable person — world traveler, painter, sportswoman, CIA analyst, PhD in experimental psychology… and one of the greatest of all science fiction writers. If you don’t recognize her name, that’s partly by her own design.

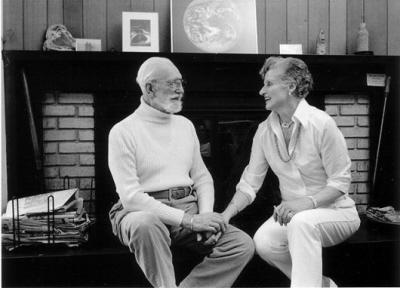

Born in 1915, from an early age Alice was a lover of this new genre that was in those days still called “scientifiction,” devouring every copy of Weird Tales, Wonder Stories, and Amazing Stories that she could find, but it wasn’t until the mid 60’s that she tried her hand at writing any SF herself. After some false starts, she completed a few stories and in 1967, when she was 51, she sent them off to John Campbell at Analog, not really expecting anything to come of it. As she considered the whole thing something of a lark, she submitted the manuscripts under a goofy pseudonym that she and her husband, Huntington (Ting) Sheldon, cooked up one day while they were grocery shopping — James Tiptree Jr. The Tiptree came from a jar of Tiptree jam; Ting added the junior.

To Alice’s professed surprise, Campbell bought one of the stories, “Birth of a Salesman.” A new science fiction writer was born, one who would, in the space of just a few years, make a tremendous impact on the genre (as two Hugos, three Nebulas, and a World Fantasy Award attest, to say nothing of the James Tiptree Jr. Award, which is given to works which expand or explore our understandings of gender).

Alice Sheldon never looked back. She also never let anyone know that James Tiptree Jr. wasn’t a man; all of her many contacts and correspondents in the SF field assumed that the courtly “Tip” who had had such a wide-ranging life and wrote such witty letters was an all-American male. (Who wouldn’t take phone calls or meet anyone — including his agent — in person and would never show up to accept any awards. What began as a joke became, without Alice’s really planning it, an elaborate deception worthy of… well, of the CIA, and a banana peel that countless readers and critics would embarrassingly slip on.)

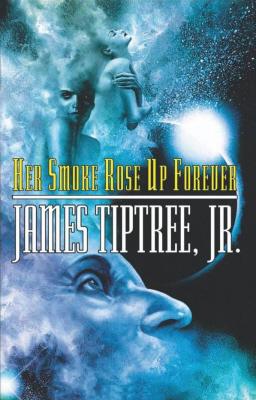

Though “he” wrote two novels (Up the Walls of the World and Brightness Falls from the Air), James Tiptree Jr. made “his” greatest contributions to science fiction in shorter (though often still fairly long) forms. (And, with your permission, that’s it for the quotation marks.) The cream of this work is collected in Her Smoke Rose Up Forever. Edited by Jeffrey D. Smith, it gathers eighteen of Tiptree’s finest stories, and is an absolutely essential volume that everyone who takes science fiction seriously should own and read and re-read cover to cover. It’s also blessedly still in print, so stop reading me and go get a copy — now. It’s the best $13.26 you’ll ever spend — I guarantee it. Don’t worry — I’ll wait until you get back. Oh, while you’re at it, you had better buy several copies — you’ll want to have them on hand to proselytize with.

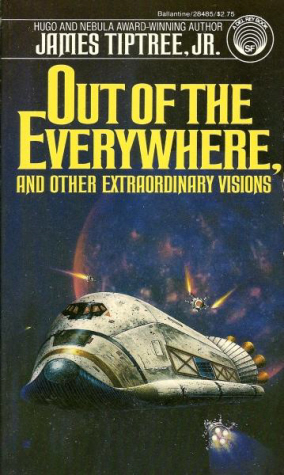

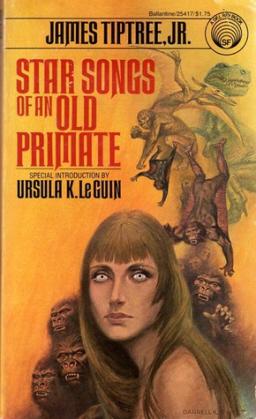

All of the stories in Her Smoke Rose Up Forever are taken from four collections that were published from 1973 to 1978 — 10,000 Light-Years from Home, Warm Worlds and Otherwise, Star Songs of an Old Primate, and Out of the Everywhere and Other Extraordinary Visions. All are out of print now, but can still be found without too much trouble. (A word of advice — avoid the Ace paperback of 10,000 Light-Years; it’s an absolutely wretched job of printing and editing. It has fifteen stories with no table of contents and more misprints than I’ve ever seen in a single book. It should have been called 10,000 Typos from Respectability. Go for the British hardcover from Eyre Methuen instead — it’s worth it.)

All of the stories in Her Smoke Rose Up Forever are taken from four collections that were published from 1973 to 1978 — 10,000 Light-Years from Home, Warm Worlds and Otherwise, Star Songs of an Old Primate, and Out of the Everywhere and Other Extraordinary Visions. All are out of print now, but can still be found without too much trouble. (A word of advice — avoid the Ace paperback of 10,000 Light-Years; it’s an absolutely wretched job of printing and editing. It has fifteen stories with no table of contents and more misprints than I’ve ever seen in a single book. It should have been called 10,000 Typos from Respectability. Go for the British hardcover from Eyre Methuen instead — it’s worth it.)

Of these four volumes, 1975’s Warm Worlds and Otherwise may be the strongest collection — more stories were chosen for Her Smoke Rose Up Forever from it (six) than from any of the other books, and they are all typical of Tiptree’s best.

“And I Have Come Upon This Place by Lost Ways” tells of an idealistic young man who, while exploring an alien planet, makes the ultimate sacrifice for science — he gives his life — only to discover that neither science nor the universe nor his fellow explorers care one whit, and the knowledge that he died to obtain will never be passed on to or benefit anyone, least of all himself.

In “The Last Flight of Doctor Ain” a brilliant biologist seeks to revenge the exploitation and brutalization of the planet he loves by removing the human parasites that have wreaked such havoc on it; he flies around the globe, releasing a specially engineered strain of influenza at each stop that will soon kill every man, woman, and child in the world, and perhaps allow the wounded — and empty — earth to heal itself.

“The Girl Who Was Plugged In” is one of the original cyberpunk stories, and tells, in a bouncy, jocular, crackling manner that belies its dark implications, of a future in which overt advertising is outlawed and corporations get around the prohibition by secretly creating beautiful young bodies that are cybernetically “remote-controlled” by human “users” who are themselves in thrall to the corporations, which promote these creations as celebrities, who will of course be seen wearing, using, and consuming just the things that their masters want promoted. For Philadelphia Burke, a sick and misshapen outcast with no friends or family, the opportunity to take on a different body and become rich and beautiful and famous is like a gift from heaven… until she discovers that some things are not permitted even to the privileged, things like love with a “real” person. Tiptree’s vision of a virtual-reality world that embraces the ultimate use of technology for economic exploitation is even more chilling and prophetic now than it was forty years ago.

In “Love is the Plan, the Plan is Death,” an enormous, spider-like alien struggles to subvert eons of evolution and define his own life on his own terms, only to tragically discover in the end that for him at least, biology really is destiny.

|

|

|

“The Women Men Don’t See” is perhaps Tiptree’s most famous story. In it a mother and her daughter, Ruth and Althea Parsons, choose to leave earth forever in the company of frighteningly incomprehensible extraterrestrials, rather than stay on this planet with the most threatening aliens of all — men. Don Fenton, the fairly-decent, average-guy narrator, cannot understand such a radical choice; surely it can’t be that bad to be a woman… which just directs readers (and Sheldon surely knew that most of the people perusing the pages of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction would be men) back to the title of the story, and leaves them pondering Ruth’s statement before she leaves earth, never to return:

Women have no rights, Don, except what men allow us. Men are more aggressive and powerful, and they run the world. When the next real crisis upsets them, our so-called rights will vanish like — like that smoke. We’ll be back where we always were: property. And whatever has gone wrong will be blamed on our freedom, like the fall of Rome was. You’ll see.

And fittingly, the final story in the book, “On the Last Afternoon,” is about nothing less than the end of the world and the loss of everything.

And fittingly, the final story in the book, “On the Last Afternoon,” is about nothing less than the end of the world and the loss of everything.

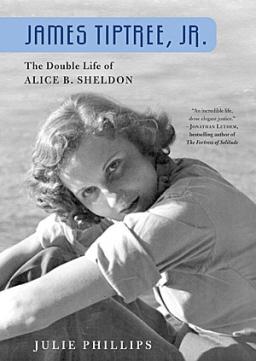

Of the six other stories in the book, three — “All the Kinds of Yes,” “The Milk of Paradise” (which Harlan Ellison included in Again, Dangerous Visions), and “Fault” are solid, rewarding stories. The other three — “Amberjack,” “Through a Lass Darkly,” and “The Night-blooming Saurian” are slight, early work, and need only concern completists, though once you start reading Tiptree you may well find yourself in that category; I did. (If you wish to further nurse your Tiptree obsession, you’ll want to read Julie Phillips’ excellent biography, James Tiptree Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon.)

As an amusing — and instructive — bonus, Warm Worlds and Otherwise also contains an introduction by Robert Silverberg, in which he roundly declares that the reclusive Tiptree has to be a man (people were beginning to wonder, especially after “The Women Men Don’t See”), because of the inarguably masculine style and sensibility of the stories.

Two years later, in 1977, Sheldon was “outed” by the detective work of some inquisitive fans. Ooops. Too bad it was, too, as her work showed a falling-off almost immediately; though she lived and wrote for ten more years, only two post-revelation stories found their way into Her Smoke Rose Up Forever. In some way Sheldon needed “Tiptree,” as a mask, or distancing mechanism, or maybe just to keep the pressure off. Anyway, it’s a good argument for minding your own business.

The surface of a Tiptree story is always lively and popping with energy; many of the early ones use a slangy, jokey, fast-talking, wisecracking diction that Sheldon largely abandoned by the time she was doing her best work. (Most of these still very readable stories are found in 10,000 Light-Years from Home. The only mature story told — and it’s told very effectively — in the earlier manner is “The Girl Who Was Plugged In.”)

But always underneath the narrative swiftness and the crackling clash of outrageous ideas, the core is midnight-dark. As John Clute and Peter Nicholls said in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, “It is very rarely that a James Tiptree story does not deal directly with death and end in a death of the spirit, or of all hope, or of the body, or of the race.” That is precisely true, and it makes the work of James Tiptree Jr. strong medicine indeed.

The Tiptree universe is a blind alley, a place where all human ambitions and aspirations are thwarted and where all human drives are overridden by the universal impulse toward self-destruction. Tiptree’s people are locked into performing acts that are as futile as they are extreme; they are the butts of a cosmic joke, doomed to war with their own biology, a biology far stronger than rationality and its feeble products, and that eternally victimizes them.

It is ironic that Sheldon’s first few stories were published by John Campbell, for at heart she was as anti-Campbellian as they come. She did not believe in any sort of human superiority or Manifest Destiny in space, or if she did, it was a very different destiny than is found in your typical space opera, as “A Momentary Taste of Being” (in Star Songs of an Old Primate and Her Smoke Rose Up Forever) makes clear. Read that story one time and you will never look at a crowded city filled with pushing, striving people in quite the same way again.

Alice Sheldon had no faith in the redemptive power of history, belief, technology, politics, progress, sex, or anything else; in place of boosterism and facile optimism, she called things as she saw them and pulled no punches, and this gives her work great force and integrity. And for all the uncompromising lack of “uplift” in her work, she’s not a nihilist; truth and decency and community exist in her work, even if only as besieged and doomed realities or as near-impossible ideals. Her characters fight for them; they lose, but they still fight.

However, even at her bleakest, and she is the bleakest SF writer I know, value is created by her wit, passion, energy, honest intelligence, and determination to be the best damn writer she could be. Fine writers abound now as always, but I don’t think anyone working in the SF genre today can come close to her.

Just how much this barren view of the way the world works was due to her sex is an open question. Certainly the slights and frustrations she daily experienced as a supremely intelligent, highly ambitious woman navigating her way through the minefields of a man-made world provided a firm foundation for a dim, disillusioned view of life, and in stories like “The Screwfly Solution,” “The Women Men Don’t See,” and “Your Faces, O My Sisters! Your Faces Filled of Light!” she unforgettably depicts the particular trap that women find themselves in.

But a wide reading of her work shows that she was never guilty of what might be called sexual provincialism; though her fury at sexual injustice was white hot, she nevertheless had a human sympathy that was broad and deep, and saw every member of our nearsighted, futilely courageous species as an unwilling prisoner of a reality they never chose.

Whatever its ultimate source, Alice Sheldon’s dark view of life wasn’t a pose or an affectation; it was a genuine expression of her view of reality, a view reinforced by the experiences of a lifetime. She surely would have agreed with another writer who was condemned in his day for his bleakness and pessimism, Thomas Hardy, who said,

It must be obvious that there is a higher characteristic of philosophy than pessimism, or than meliorism, or even than the optimism of these critics — which is truth. Existence is either ordered in a certain way, or it is not so ordered, and conjectures which harmonize best with experience are removed above all comparison with other conjectures which do not harmonize.

Alice Sheldon’s dark conjectures clearly harmonized with the world as she saw it, and embodied a view of life that can command our respect even if we withhold our full assent, especially in light of the grim path that it ultimately led her down. In 1987, with her health and Ting’s in rapid decline, unable to write, exhausted and demoralized by decades of battling crippling clinical depression, she shot Ting while he slept and then killed herself.

The life of the traveler, painter, sportswoman, CIA analyst, and psychologist came to an end. The work of the writer continues to enlighten, challenge, and move — it endures.

Alice Sheldon is dead. Long live James Tiptree Jr.

Thomas Parker’s most recent article for us was “Tell Me Why.”

Thank you for this. Her stories always broke my heart – in a good way.

Her work was the best.

[…] “The Woman Who Was a Man Who Was a Woman: Alice Sheldon and James Tiptree Jr.” is a fine proifile by Thomas Parker on Black […]