Is The Lord of the Rings Literature?

Part 2 of a 2-part series

Part 2 of a 2-part series

Part 1 of this article set the stage for the question, Is The Lord of the Rings literature? Part II examines six criteria commonly used to define works of high literary quality and applies them to The Lord of the Rings.

1. Popular appeal

The argument against: The Lord of the Rings might be popular, but that doesn’t make it literature.

The counterargument: There’s popular, and then there’s an omnipresent, mammoth, overshadowing level of popularity.

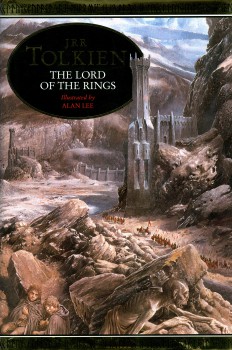

How popular is The Lord of the Rings? At last count, it has been translated into 57 languages and is the second best-selling novel ever written, with over 150 million copies sold. Its also a repeat winner of multiple international contests for favorite novel (note the broad term novel, not just fantasy novel). For example:

- In 1997 it topped a Waterstone’s poll for Top 100 Books of the Century.

- In 2003 a survey (The Big Read) was conducted in the United Kingdom to determine the nation’s best-loved novel of all time. More than three quarters of a million votes were received, and the winner was The Lord of the Rings.

- A 1999 Amazon poll administered to its customers yielded the same result.

In short, readers of all stripes, from all around the world, adore this book more than just about any other.

All that said, I will fully admit that this is the least convincing argument, because mass appeal is not necessarily a good indicator of quality. See Justin Bieber. So let’s look at some other criteria.

2. Critical reception

The argument: Most literary critics think The Lord of the Rings is a joke and think the books’ fans are like Trekkies–only without discerning taste.

The counterargument: Sure, some critics think The Lord of the Rings is a joke, and many others believe that it’s not of literary quality. But many other distinguished academics and critics have argued passionately for its greatness.

As mentioned in Part I of this article the mere existence of Tom Shippey’s J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century and The Road to Middle Earth are antidote to the claim that The Lord of the Rings is lightweight genre fiction. The ball is now in the opposing critics’ court to answer Shippey’s claims for Tolkien as a great writer of the 20th century.

But although Shippey—scholar of medieval literature at Oxford University—represents the peak of pro-Tolkien criticism, he’s really only the tip of the iceberg. Some other prominent academics and writers that have sung the praises of The Lord of the Rings include:

• C.S. Lewis, Professor of Medieval and Renaissance English at the University of Cambridge

• W.H. Auden, noted author and poet

• John Bowers, Professor of English at the University of Nevada

• Michael Drout, Chair of the department of English at Wheaton College

• Verlyn Flieger, Professor at the University of Maryland

• Jane Chance, Professor of English at Rice University

• Corey Olsen, English Professor at Washington College

I can’t give an accurate count of the formal, academic studies devoted to Tolkien and his works, but I’m comfortable stating that they exceed a hundred. You can also find academic conferences dedicated to Tolkien, and others on medieval studies in which Tolkien studies/The Lord of the Rings are a component. The Lord of the Rings has been taught in colleges since at least the 1970s (Chance taught Tolkien at Rice in the spring of 1976), and there’s a peer-reviewed academic journal (Tolkien Studies) devoted to the author and his works.

I can’t give an accurate count of the formal, academic studies devoted to Tolkien and his works, but I’m comfortable stating that they exceed a hundred. You can also find academic conferences dedicated to Tolkien, and others on medieval studies in which Tolkien studies/The Lord of the Rings are a component. The Lord of the Rings has been taught in colleges since at least the 1970s (Chance taught Tolkien at Rice in the spring of 1976), and there’s a peer-reviewed academic journal (Tolkien Studies) devoted to the author and his works.

Nor is positive critical reception limited to professors and academics pre-disposed to Tolkien due their intimate familiarity with the medieval. Time magazine critics Lev Grossman and Richard Lacayo released their 100 best english language novels since 1923, which included J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. James Parker of The Boston Globe, Andrew O’Hehir of Salon.com, and many other representatives of prominent general media outlets have sung its praises as a lasting work of art.

But in the end, this argument is also not enough. An appeal to authority is just that, and one can point to other critics with equally ardent negative opinions. So let’s examine some other arguments.

3. Influence on later writers

The argument: The Lord of the Rings was one man’s world-building project, pursued with an unhealthy obsession. It’s a unique artifact but hasn’t had the impact on other writers that great literature does.

The counterargument: Actually, The Lord of the Rings has influenced countless authors.

The Lord of the Rings transformed a genre. Nothing has been the same since, and every fantasy author since its publication has had to cope in one way or another with its influence. Some have done so with slavish imitation, others with visceral opposition. In his study of fantasy literature Rings, Swords and Monsters, author and professor Michael Drout labels this an “anxiety of influence.” The Lord of the Rings is still the standard by which fantasy is measured today; see the frequent use of “The American Tolkien” in reviews of George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series.

If you want to see the sheer breadth of the influence of The Lord of the Rings laid out in full, I recommend Karen Haber’s Meditations on Middle-Earth. In here you’ll find lively essays by authors such as Ursula LeGuin, Raymond Feist, Terry Pratchett, George R.R. Martin, Michael Swanwick, Poul Anderson, and many others, all expressing their deep appreciation and in some cases outright awe of The Lord of the Rings and the immense influence it had on their careers. Here’s a brief snippet of what Martin had to say:

Most contemporary fantasists happily admit their debt to the master (among that number I definitely include myself), but even those who disparage Tolkien most loudly cannot escape his influence. The road goes ever on and on, he said, and none of us will ever know what wondrous places lie ahead, beyond that next hill. But not matter how long and far we travel, we should never forget that the journey began at Bag End, and we are all still walking in Bilbo’s footsteps.

But while the influence of The Lord of the Rings is plain, it’s arguably largely confined to the fantasy genre, not other genres (including mainstream writers of literary fiction, which some now consider its own genre). For those who believe that fantasy is inherently non-literary, this argument likely won’t convince them.

So what about the methods Tolkien used to write it?

4. Use of literary technique

The argument: When was the last time you tried to read The Lord of the Rings? It’s pedestrian, with bad poetry to boot. Tolkien was not a good craftsman, great world-builder though he may be.

The counterargument: While writing The Lord of the Rings Tolkien took advantage of all the literary techniques available to him, both ancient and modern. Though many are subtle, they exist.

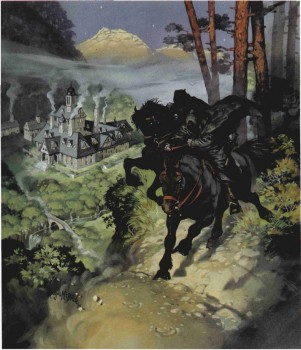

The Lord of the Rings may share much in common with medieval romance, but it’s also many ways a 20th century novel, written with (for its time) the latest “technology” of writing craft. It contains allusions to old Northern myth and Christianity, as well as symbolism, foreshadowing, and cosmic and dramatic irony (see Matthew David Surridge’s fine piece on this latter element here on Black Gate ). It represents the work of a writer with full command of myth-making developing his own great myth, for example with The Red Book of Westmarch, which is a meta-textual commentary on the very text of The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien also leaves his readers suspended in the dark like any good dramatic writer should, for example when the Black Gate clangs shut on Sam (and the reader) at the conclusion of The Two Towers. That must have been quite the cliff-hanger in November 1954 when readers had to wait 11 months until the publication of The Return of the King in October 1955.

Shippey argues in Author of the Century that The Lord of the Rings encompasses all five literary modes detailed in Northrop Frye’s classic study An Anatomy of Criticism. These include myth, romance, high mimesis (think tragedy, or epic), low mimesis (classical novel, think Henry James) and irony, the last characterized by its comic anti-heroes. The hobbits vacillate between low mimesis with a few lapses into irony, with characters like Sauron and Bombadil clearly rooted in the world of myth.

Many critics posit that deep characterization is the purest function of literature, and that novels must feature a main character or characters that undergo a profound change over the course of the narrative. I won’t argue that LOTR has a deep, sweeping character arc to any of its characters; it does not (though Gollum/Smeagol arguably does, and Frodo is certainly substantially changed from his journey). But its entire cast and crew of characters adds up to the sum of the human condition. Aragorn is nobility of the spirit, Sam is loyalty, Frodo dogged determination, Gollum lust, Denethor despair, Boromir pride, etc. Taken together as a whole, this panoply of characters depicts us, and offers a profound picture of what it means to be human.

Many critics posit that deep characterization is the purest function of literature, and that novels must feature a main character or characters that undergo a profound change over the course of the narrative. I won’t argue that LOTR has a deep, sweeping character arc to any of its characters; it does not (though Gollum/Smeagol arguably does, and Frodo is certainly substantially changed from his journey). But its entire cast and crew of characters adds up to the sum of the human condition. Aragorn is nobility of the spirit, Sam is loyalty, Frodo dogged determination, Gollum lust, Denethor despair, Boromir pride, etc. Taken together as a whole, this panoply of characters depicts us, and offers a profound picture of what it means to be human.

As for the quality of the prose in The Lord of the Rings, that’s a difficult argument to make, and highly subjective. But if you’re not moved by the following passage, and the skill with which it is written, Tolkien is not for you:

Even as they gazed, the Silverlode passed out into the currents of the Great River, and their boats turned and began to speed southward. Soon the white form of the Lady was small and distant. She shone like a window of glass upon a far hill in the westering sun, or as a remote lake seen from a mountain: a crystal fallen in the lap of the land. Then it seemed to Frodo that she lifted her arms in a final farewell, and far but piercing-clear on the following wind came the sound of her voice singing. But now she sang in the ancient tongue of the Elves beyond the Sea, and he did not understand the words: fair was the music, but it did not comfort him.

Unfortunately this arguement is the hardest to prove with concrete evidence, as artistic quality is largely in the eye of the beholder. So how about the question of whether it has anything to say about what it means to be human, another traditional characteristic of great literature?

5. Engagement with the human condition

The argument: The Lord of the Rings has Elves and Dwarves and is centered around a pair of hobbits. It does not address the human condition.

The counterargument: Hobbits are middle-class Englishmen in everything but stature and feet, and so their concerns are ours.

The Lord of the Rings confronts some of the most perplexing questions about ourselves, our roiling internal conflicts and contradictions, and mankind’s propensity for great good and unspeakable evil. A few examples include:

Free will vs. determinism. The time in which we live and the circumstances thrust upon us are beyond our control. Forces exist that try to exert or impose their will for good or ill. But while these forces exert influence, they cannot wholly divest control from beings of free will. Bilbo and Frodo choose to let Gollum live, acts of Mercy that are beyond the striving wills of even the greatest powers, and so our fate, for good or ill, is ours to make. “For even the very wise cannot see all ends,” Gandalf says. The Lord of the Rings emphasizes that people can be decent and good if they choose to act that way; once we begin down life’s path and begin to succeed or fail and make adult choices on “The Road,” we create our own fate, one that history will judge us by. Tolkien showed us the hard straight road and we can choose to follow it. (To quote Gene Wolfe, “Freedom, love of neighbour, and personal responsibility are steep slopes; he could not climb them for us — we must do that ourselves. But he has shown us the road and the reward.”). There is a place for morality, for responsibility, and for obligation.

The nature of evil. Many critics claim that LOTR has a childlike view of evil. Sauron is the Dark Lord and arrayed against him are forces of stainless good. First of all, there is such a thing as evil—see Hitler. The easy and politically expedient method of dealing with evil is compromise, but that can prove disastrous (see Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement policy for dealing with the Nazis in the early days of WWII, which failed miserably). Sometimes, war is necessary. Secondly, evil takes many forms in The Lord of the Rings that should be familiar (perhaps uncomfortably so) to its readers. Many evil people and beings in Middle-Earth were once good; Tolkien does not depict evil as some entity created from whole cloth without, but is the result of succumbing to weakness within ourselves. Wraiths for example were once great kings of men, but accepted the gifts of Sauron and became twisted inside, losing their sense of selfhood. Saruman, once a member of the White Council, was seduced by power and his own voice. Gollum was once the decent hobbit Smeagol but an unchecked lust for material possessions brought him to his lowly state. And so on.

The nature of evil. Many critics claim that LOTR has a childlike view of evil. Sauron is the Dark Lord and arrayed against him are forces of stainless good. First of all, there is such a thing as evil—see Hitler. The easy and politically expedient method of dealing with evil is compromise, but that can prove disastrous (see Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement policy for dealing with the Nazis in the early days of WWII, which failed miserably). Sometimes, war is necessary. Secondly, evil takes many forms in The Lord of the Rings that should be familiar (perhaps uncomfortably so) to its readers. Many evil people and beings in Middle-Earth were once good; Tolkien does not depict evil as some entity created from whole cloth without, but is the result of succumbing to weakness within ourselves. Wraiths for example were once great kings of men, but accepted the gifts of Sauron and became twisted inside, losing their sense of selfhood. Saruman, once a member of the White Council, was seduced by power and his own voice. Gollum was once the decent hobbit Smeagol but an unchecked lust for material possessions brought him to his lowly state. And so on.

The problem of death. Many critics (most famously Michael Moorcock in his utterly wrongheaded esssy “Epic Pooh”) argues that The Lord of the Rings fails as serious literature because it recoils from death, and offers an artificial, happy, nursery-room ending. On the contrary: The entirety of The Lord of the Rings can be viewed a metaphor for death. Frodo was not coming back over the sea in that gray ship. There are references to white shores and beyond them a far green country under a swift sunrise, and the hope of something better, but there are no explicit references to a god in The Lord of the Rings who can deliver on such promises. Tolkien’s works actively grapple with the terrible reality and uncertainty of our mortality.

Its engagement with the human condition in my opinion makes for a stronger claim for The Lord of the Rings. But in the end, does The Lord of Rings engage wider reality? Is it really just personal wish-fulfillment set in a fantasy world, or can it help broaden our perspectives of the world around us? Is it still relevant today?

6. Applicability/commentary on reality

The argument: The Lord of the Rings is fantasy, it’s not “realistic,” so by definition it cannot be literature.

The counterargument: So now works like 1984 and Moby Dick don’t qualify as literature? All fiction is made-up. Middlemarch has no more basis in reality than Hobbiton.

The argument that fantasy is not art because it does not engage reality is flat-out wrong, of course. Great works of fantasy engage real issues, but do so through symbolism, allegory, or applicability. The Lord of the Rings can be read as a reaction to the rise of modernism, or as a commentary on the World Wars. It ain’t just about elves and dwarves, and it’s got plenty to say about our predicament, including our recent past and the here and now of the 21st century.

Central to LOTR is the departure of the elves for the Grey Havens and the sense that magic is leaving along with them, to be replaced by the prosaic age of men. In Tolkien and the Great War, author John Garth says that this tenet parallels Tolkien’s own experiences in 1915, when the Oxford campus was emptied of its undergraduates due to the call of war. Like the Elves many of these young men would never return home. Melancholy pervades LOTR, the sense that something has been lost: a simpler, more idyllic time.

Tolkien was a veteran of World War I and The Lord of the Rings shows clear influences of his combat experiences. Tolkien wrote in a letter that he drew his inspiration for the landscape of the Dead Marshes from the Somme, while the actions of Sam and Frodo strugging through Mordor to the end of their endurance mirrors the great acts of unrecorded bravery of the rank and file “Tommies” whom Tolkien so admired. Their only hope was to get back home.

Tolkien was a veteran of World War I and The Lord of the Rings shows clear influences of his combat experiences. Tolkien wrote in a letter that he drew his inspiration for the landscape of the Dead Marshes from the Somme, while the actions of Sam and Frodo strugging through Mordor to the end of their endurance mirrors the great acts of unrecorded bravery of the rank and file “Tommies” whom Tolkien so admired. Their only hope was to get back home.

There’s been much speculation that the events of The Lord of the Rings are an allegory for WWII, though Tolkien in a strongly worded forward to The Lord of the Rings denies this. Nevertheless, we are all of our age, and do not write in a vacuum. There are parallels (or as Tolkien might say, “applicability”) between The Lord of the Rings and the second great conflict of the 20th century as well as the first. For example, when Gandalf tells Frodo that the Shadow has returned to Mordor, Frodo says, “I wish it need not have happened in my time,” and Gandalf replies, “so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide.” As Shippey explains, “The phrase “in my time” recalls Neville Chamberlain’s now infamous promise, on his return from capitulating to Hitler in Munich in 1938, that he bought ‘peace in our time’. He did not.”

The Lord of the Rings emphasizes alliances over unilateral actions. Different cultures and peoples must set aside their differences and work together to confront evil. Rohan and Gondor, two former allies grown cold with suspicion and grievances large and small, are ultimately able to recognize evil and realize that they must confront it together or perish. This too hearkens to events circa 1941.

The Lord of the Rings also provides commentary on modernism and the often equivocal nature of progress. There are some who view progress as a straight line ascending to some scientific singularity in which mankind will presumably perfect itself. Others do not share this opinion, Tolkien included. In the chapter “The Scouring of the Shire” it’s plain that industrialization and urbanization can also wreak harm. Tolkien recognized progress as inevitable, but he thought it was as much cause for weeping as joy (see pollution, and urban decay).

At the end of The Lord of the Rings the Third Age draws to an end. A time of magic and wonder passes from the world, and the Fourth Age is heralded in. Middle-earth passes to a time of men, and systematized education, and modern conveniences, and beneficial science. Tolkien, even in his fantasy world of Middle-Earth, knew that life went on, and must go on, for better or worse. But he also believed that change is not always for the better. In Tolkien’s time mechanized warfare, industrial pollution, and the threat of atomic annihilation offered compelling proof. His preference for fields instead of parking lots, and skyscrapers instead of trees, continues to resonate today, in our personal lives and in the political arena.

Conclusion

So there are my six arguments in support of the question. Note that this exercise does not imply that The Lord of the Rings is perfect, nor above criticism. But I’d like to think that we’ve moved beyond the “fad” stage, a term outraged critics employed to explain the immense popularity of Tolkien’s work back in the 1960s. Many classics were savaged by critics upon their release, and The Lord of the Rings is no exception. But discussion of works like The Catcher in the Rye or The Grapes of Wrath has now moved to a more rational, sane level of discourse. No one today still asks whether they should have been written in the first place. This question is sadly still being asked by some critics of The Lord of the Rings, and it shouldn’t be.

It’s been nearly 60 years since the publication of The Lord of the Rings and it’s rather obvious that it’s not going anywhere. While we’re all certainly entitled to dislike or even hate Tolkien’s masterwork, just like the legions of high school students who despise every page of The Great Gatsby, it’s time to drop the elitist notion that it’s somehow a lesser work. You don’t have to take my word for it, the evidence (as I hoped to show above) is compelling. The Lord of the Rings is a work of exceptional quality, adored by readers, admired by writers, and respected by critics. It speaks to us and our unique plight as humans and provides a lens through which we can interpret modern and historical events.

Which I guess makes it, well, literature, and of an exceptional nature.

A very good article and I agree with you almost entirely. The Lord of The Rings is literature. It’s a great work and it’s simply silly that people refuse to recognize that because it’s also a commercial juggernaut.

One slight argument, I guess. I don’t think the third argument here is very strong at all. In my experience, it’s too easy for skeptics to reject that argument on the grounds that the people influenced by Lord of the rings are not of literary value themselves. And if that’s the case, it proves little that Tolkien influenced several generations of lowbrow writers. That argument is not convincing unless you establish that the people Tolkien influenced are first-rate writers as well, I think.

Interesting that there are those who still stubbornly maintain that Lord of the Rings is not literature. I was introduced to it by my English teacher, so there a those in academia who get it. 😉

Great article. I wasn’t aware such a useless debate was even raging. Over here in England it would be referred to as a storm in a teacup.

To say that Tolkien is not real “literature” boils down to one thing, elitist snobbery. Because the genre involves elements of fantasy, denialist won’t take it seriously, even when it meets and exceeds the other “greats.”

As well, denialist will never have the influence Tolkien has had. This is often a motivation for many people to try and tear someone down.

Just as a cool side note, I live near Harrogate, England, where Tolkien once spent time recovering from trench fever.

“Hmm, I wonder if this massive story book written in human language is literature… but there are goblins in it so that must mean… it’s not literaturez!!!”

That’s what I got from this article. Literature is literature, I really cannot fathom where anybody got the idea that LotR is not literature.

Anthony,

When print culture began in the late seventeenth century (and continuing on until about the 1960s or so), attempts were successfully made to differentiate “good” literature from “bad” literature. This binary has (admittedly) shifted over time, but it still exists. The binary exists to: 1)Make a “literate” elite- either middle class/ brow (present) and academic/ scholar (future) and 2) To create a separate “space” in which the poor, lesser educated, outsiders, etc. can read while reinforcing the assumptions of the “literate” class.

Is it stupid? Yes, but the modern West is one for pretentious binaries.

Thanks for the comments, everyone!

One slight argument, I guess. I don’t think the third argument here is very strong at all. In my experience, it’s too easy for skeptics to reject that argument on the grounds that the people influenced by Lord of the rings are not of literary value themselves. And if that’s the case, it proves little that Tolkien influenced several generations of lowbrow writers. That argument is not convincing unless you establish that the people Tolkien influenced are first-rate writers as well, I think.

Hi Doug, I agree to a degree, as I struggled to find examples of mainstream writers that Tolkien has definitively influenced (if anyone knows any, I’d love to hear them). That said, I firmly believe that Ursula LeGuin is a writer of the first class without question. I also failed to mention that Tolkien heavily influenced Gene Wolfe, who is also highly regarded as one of the best living writers in any genre.

Interesting that there are those who still stubbornly maintain that Lord of the Rings is not literature. I was introduced to it by my English teacher, so there a those in academia who get it.

I’m always glad to hear about LOTR being introduced in the classroom. Kudos to your teacher!

To say that Tolkien is not real “literature” boils down to one thing, elitist snobbery. Because the genre involves elements of fantasy, denialist won’t take it seriously, even when it meets and exceeds the other “greats.”

I agree, although I think we’re slowly starting to see fantasy and SF gain acceptance in literary circles. Slowly.

Literature is literature, I really cannot fathom where anybody got the idea that LotR is not literature.

sftheory1 explained it as well as I could. The term “literature” is highly problematic (technically a leaflet handout at the airport is literature), but what I’m referring to is the hard-to-define quality that separates popcorn genre or books of empty action vs. works that have lasting cultural significance, or that have something important to say about “the big questions,” etc.

A great article. thought I’d list some of the counter arguments I’ve gotten defending Tolkien over the years.

Popularity: Popularity has nothing to do with whether something is literature or not. I actually tend to agree with this -I’d rather not subject literature to a popular referendum. though, the massive sales must say something.

Scholarship: the writers and academics which take fantasy seriously are maladjusted social introverts, who crawled into fantasy as children and never bothered to come out. Several academics I’ve known would say the same about Medieval Literature as well.

Literary technique: There are good passages in LotR, but there are equally bad ones as well. Some sentences become so lost in the labyrinthine paragraphs, they are unable to extricate themselves and die (wile I disagree, I was so impressed with that statement, I wrote it down).

Human condition: Usually these people’s response is to yell “Dwarfs!” very loudly, and begin to stuff cotton in their ears. I think people who don’t understand the more profound parts of LotR can’t be persuaded. It’s a question of resonance, and thus a subjective thing.

I too suspect that Tolkien’s enormous influence doesn’t count because the writers aren’t literary.

And I suspect they can’t be persuaded. It’s not for nothing that 1984 and Brave New World are the literary’s idea of the SF classics. Both being satires, they are really about the modern world. You can see it in any literary criticism that desperately tries to turn fantasy into an allegory so they don’t have to grapple with other worlds.

Darangrissom: I agree with your comment about popularity not equating to quality, but on the other hand the immense sales of The Lord of the Rings appear to cast a lot of doubt on your third counter argument (literary technique): If Tolkien’s prose is so bad and hard to read, why are people buying and reading his stuff in droves, over multiple generations? It doesn’t jibe.

I too suspect that Tolkien’s enormous influence doesn’t count because the writers aren’t literary.

Again, I would put Ursula Le Guin’s stuff up against almost any critically acclaimed mainstream writer of the last 50 years.

Strong article, Brian! A couple points:

— Popularity’s a tricky thing. On the one hand, polls are capable of manipulation, block voting, and so forth. And popularity seems rarely to be an accurate measure of the lasting value of a work. On the other hand, part of Tolkien’s project was to write a mythology, and the popular response to his book suggests he may have succeeded at that (to the extent modern fiction can serve as myth).

— Influence on other writers: Junot Diaz was clearly influenced by Tolkien. A.S. Byatt’s written well of him also (and referred to him in some of her novels). Michael Chabon’s mentioned him once or twice as well. I suspect as the current generation of lit writers produces more and more stuff, we’ll see more and more Tolkien influence.

Good post!

Brian Murphy,

Please do not think that I was espousing any of the arguments I listed. I was simply repeating what several of my English professors use when discussing the literary merits of Tolkien.

As to the third counter argument; I never said it was hard to read, just long-winded and meandering. Besides, bad prose is no bar to something becoming a best seller, or even a perennial favorite. You can say much the same about C.S. Lewis’ writing as well, and look at his sales. I consider it more a hall-mark of Oxford academics than I do of fantasy writing.

[…] for a like comparsion) and time has proven many critics wrong, from the low to the very highest. By any measurable standard The Lord of the Rings has proven to be literature of the highest quality and among the best books […]