The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith PART II: The Book of Hyperborea

By Ryan Harvey

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

Legend says that after his exile from Iceland, Erik the Red voyaged to a frozen island and settled there in 982 C.E. Deciding not to scare away new settlers with an intimidating name like “Iceland,” he dubbed the place “Greenland.” We can scoff at Erik’s bit of dishonesty-in-advertising, and certainly any homesteaders who fell for his marketing ploy would have felt like cleaving Mr. The Red’s skull with a scramasax, but perhaps Erik knew something about Greenland’s deeper history: the lost chronicles that fantasy writer Clark Ashton Smith revealed in his stories about a far northern continent in its younger days before glaciers claimed it, when wizards and elder gods and wily thieves and greedy moneylenders crisscrossed its steamy jungles and ebony mountains and opulent cities. A vanished civilization known as…Hyperborea.

Legend says that after his exile from Iceland, Erik the Red voyaged to a frozen island and settled there in 982 C.E. Deciding not to scare away new settlers with an intimidating name like “Iceland,” he dubbed the place “Greenland.” We can scoff at Erik’s bit of dishonesty-in-advertising, and certainly any homesteaders who fell for his marketing ploy would have felt like cleaving Mr. The Red’s skull with a scramasax, but perhaps Erik knew something about Greenland’s deeper history: the lost chronicles that fantasy writer Clark Ashton Smith revealed in his stories about a far northern continent in its younger days before glaciers claimed it, when wizards and elder gods and wily thieves and greedy moneylenders crisscrossed its steamy jungles and ebony mountains and opulent cities. A vanished civilization known as…Hyperborea.

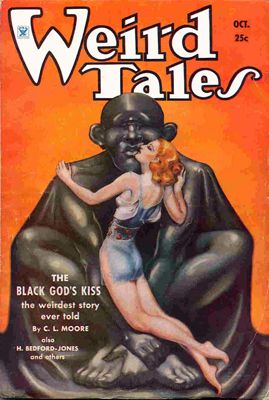

Of Clark Ashton Smith’s three major fantasy series, Hyperborea had the worst sales record during his lifetime. Smith finished ten stories about the ancient continent, and most bounced back and forth from various magazines until they finally found homes. The majority ended up in Farnsworth Wright’s Weird Tales (sometimes after multiple tries), but others landed in ephemeral pulps or non-paying fanzines.

Reading the Hyperborean stories today it is easy to understand why Clark Ashton Smith had such a burdensome time selling them: nowhere else in his canon does he so artificially elevate his prose style. Although the stories of Zothique swim in decadent and decaying imagery, Hyperborea drowns in sententious language that Smith uses for ironic effect. “The Coming of the White Worm” might rank as the most obtusely written of all his stories, and it only saw print after Smith considerably simplified the language.

Posthumously, Hyperborea has gained stature among Smith’s works, and the stories appear frequently in anthologies. The continued popularity of the Hyperborea stories today comes from two factors: their links to H. P. Lovecraft’s famous “Mythos,” and their doses of grotesque ironic humor.

Situating Hyperborea

Situating Hyperborea

Exactly what, where, and when is Hyperborea?

The concept originates with the Greeks; the word means “beyond the north wind.” Herodotus mentions Hyperborea as a land far to the north of mainland Greece, filled with joyous people who lived an Elysian existence under warm twenty-four hour sunshine. In some versions of the myth of Perseus, the hero seeks for the Gorgons after passing the land of the Hyperboreans.

Smith includes little of this Grecian concept of Hyperborea except that of a northern land existing in a warm state, and borrows more from modern theories about the land. In the traditions of later literature, Hyperborea thrived coeval with the other mythic civilizations of Atlantis, Lemuria, and Mu (which all receive mention in Smith’s stories) that Helena Blavatsky promoted in Theosophy, a pan-religious gnostic movement she founded in 1875. Smith acknowledged his debt to Blavatsky’s bizarre occultism:

Theosophy, as far as I can gather, is a version of esoteric Yoga prepared for western consumption, so I dare say its legendry must have some sort of basis in Oriental records. One can disregard the theosophy, and make good use of the stuff about elder continents, etc. I got my own ideas about Hyperborea, Poseidonis, etc. from such sources, and turned my imagination loose. (Letter to H. P. Lovecraft, 1 May 1933)

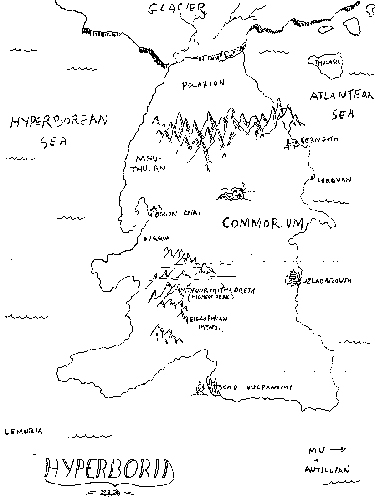

In “Ubbo-Sathla,” Smith states that Hyperborea was “supposed to have corresponded roughly with modern Greenland, which had formerly been joined as a peninsula to the main continent.” The setting and geography agree with this assessment: unlike the other lost civilizations of Lemuria, Mu, and Atlantis, Hyperborea did not sink from sight but vanished under an advance of ice. It seems logical that the land mass still exists, and the glacier-covered island of Greenland, large enough to almost qualify as a continent, fills the Hyperborean bill.

Smith mentions that the stories occur “in the last centuries before the onset of the Great Ice Age,” possibly meaning the last long interglacial period, the Eemian Interglacial (130,000-70,000 B.P.). The mention of mammals common to this epoch, such as saber-tooth cats, aurochs, and mammoths, further places the period as the recent Pleistocene, before the start of human civilization. However, in “Ubbo-Sathla,” Smith gives a different period in Earth’s history for Hyperborea: the Miocene Period, approximately twenty-three million years past, which concluded in a glacial advance. Dinosaurs, such as a Tyrannosaurus and an Archaeopteryx, appear in “The Seven Geases” alongside mentions of saber-tooth tigers and mammoths. With so many contradictions, it seems that locating Hyperborea in time serves little purpose. It exists in a nebulous past outside of our own understanding of time.

The ten stories and other references in Smith’s fiction and letters provide enough information to craft a general overview of Hyperborea’s geography and history. In this warm interglacial period, thick moist jungles coat much of the middle of the continent. The black range of the Eiglophian Mountains cuts through the middle of the land and lies a day’s march from the two capital cities, Commoriom and Uzuldaroum. Most of the foulest deities of Hyperborea live in caverns beneath the tallest of the Eiglophians, Mt. Voormithadreth. The citizens abandoned the older capital Commoriom, “superb and magisterial…opulent among cities,” during the reign of King Loquamethros because of the prophecy of the White Sybil of Polarion. The fleeing population established a second capital only a few leagues away, Uzuldaroum. The northernmost peninsula is Mhu Thulan (derived from the Latin “Ultima Thule”), where the wizard Eibon dwells in his pentagonal tower. The largest city in Mhu Thulan is Cerngoth. Another important city, Iqqua, which has its own line of kings, lies close to Mhu Thulan. Above Mhu Thulan looms the icy waste of the enormous glacier of Polarion. Eventually, as the White Sybil augured, the glacier of Polarion destroys Hyperborea and leaves behind the land we know as Greenland. Only the stories of the prophet Klarkash-Ton survive to tell us of the vanished wonders of Hyperborea.

The Clark Ashton “Smythos”

The Hyperborean cycle constitutes Clark Ashton Smith’s largest contribution to what August Derleth later termed “The Cthulhu Mythos” (referred to here simply as “The Mythos”), H. P. Lovecraft’s loose pantheon of star-born primordial gods and their influence on earth.

Lovecraft, one of the most popular scribes of Weird Tales and the most celebrated horror author of the last century, started an industry of terror when he published “The Call of Cthulhu” in 1926. This story of a reawakening cosmic evil that causes a scholar to reassess the rationality of existence had a tremendous effect on the horror field. Lovecraft maintained a voluminous correspondence with other authors in which they swapped ideas and concepts that tied in with Lovecraft’s gradually growing cabal of garbled-named gods and fictional tomes of mind-searing lore. Long after Lovecraft’s passing in 1937, other writers would continue to pour out new pastiches of his “Mythos,” creating a strange and misunderstood horror sub-genre.

But Clark Ashton Smith’s expeditions into the Mythos were not pastiches like those of August Derleth or the young Ramsey Campbell. His take on the Mythos is so uniquely his, that a few have jokingly called it the ‘Clark Ashton Smythos.’ The cosmic Old Ones that appear so distant and incomprehensible in Lovecraft’s work and those of his imitators take on the mantle of cruel, capricious jesters in Smith’s renditions. Will Murray notes that “Smith’s Old Ones were more in the nature of the Greek Gods, meddling in human affairs and concerns despite their often outlandish names and semi-anthropomorphic forms, and issuing pronouncements in human tongue.” The Greek pantheon connection works for the more humorous of the Hyperborean stories, but there is also a link to the grim gods of the Norsemen, particularly in a subset of the stories about the slow death of Hyperborea beneath the advancing glaciers, where the ironic humor of the series nearly vanishes. Either way, Smith’s cosmic terrors have a direct presence in his stories as characters in a way that Lovecraft’s never do.

Smith’s most important additions to the Mythos first appeared in Hyperborea: the tome of lore known as The Book of Eibon (Livre Ivonis in its French translation), and the toad god Tsathoggua. Tsathoggua runs through the Hyperborean stories as a common motif and sets the ironic-comic tone for much of the cycle. The toad god shows how far Smith’s vision of the Mythos veers from Lovecraft’s. In “The Door to Saturn,” Smith gives Tsathoggua a typical Lovecraftian background: he drifted down from the stars in forgotten eons (using Saturn as a ‘way-station’) and established himself deep underground on earth in pre-human days, eventually cultivating slavish followers. However, in “The Tale of Satampra Zeiros,” Smith gives a physical portrait of Tsathoggua quite unlike Lovecraft’s cosmic, mind-blasting terrors:

He was very squat and pot-bellied, his head was more like that of a monstrous toad than a deity, and his whole body was covered with an imitation of short fur, giving somehow a vague suggestion of both the bat and the sloth. His sleepy lids were half-lowered over his globular eyes; and the tip of a queer tongue issued from his fat mouth. In truth, he was not a comely or personable sort of god….

In Tsathoggua’s portraiture lurks something clownish and grotesquely funny. This dark-comic feeling fits the Hyperborean cycle, and the ironic final phrase might sum up the dry sarcasm of much of the series.

(Smith apparently had an affinity for the toad god. In a 1934 letter to Richard Searight, he wrote: “Tsathoggua is one of my specialties!”)

Clark Ashton Smith scholars have often overstated the humorous aspect of Hyperborea and let it color their perceptions of the series. Not all the stories contain black comedy and sarcastic language as in “The Tale of Satampra Zeiros” or the bizarre “The Seven Geases.” Three of the stories form a sub-cycle about Hyperborea’s doom, and Smith wrote them close together. In these stories he leans toward the crepuscular tone of his popular Zothique series, which started to emerge while he was deep in the Hyperborean stories. Additionally, the work “Ubbo-Sathla” stands outside the rest of the series in tone and setting, and reads like an homage to Lovecraft’s style. Sardonic comedy plays a large part in Hyperborea’s appeal, but many more levels lay beneath its thin coating of ice.

The Book of Hyperborea

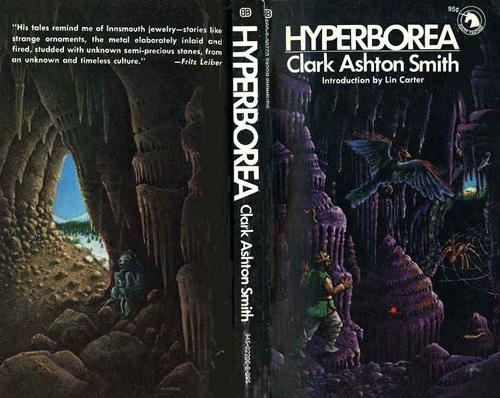

Smith planned to collect the stories of Hyperborea into a single volume with the hope of finding a publisher. He called the proposed collection The Book of Hyperborea, the name that Necronomicon Press used for its 1996 anthology. I have chosen to list the stories in the order of their composition, instead of the chronological order that Lin Carter devised for his Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series or the version that Smith listed in his Black Book because the development of the series appears more obvious in this arrangement.

“The Tale of Satampra Zeiros”

“The Tale of Satampra Zeiros”

Completed November 1929. First published in Weird Tales, November 1931.

This first-person narrative, the work of thief and raconteur Satampra Zeiros, sets the tone for the bizarre stories that follow. Our penurious narrator embellishes his brief horror story about an unfortunate looting expedition with such pompous language that it makes the horrific incident into a sarcastic joke-almost. The terror aspect peeps through just enough, and structurally the narrative follows a familiar horror outline. But the joy of the story comes from the way that Smith flips the situation upside-down with Satampra Zeiros’ language that distances him from not only the terror of the action, but also from his career as a thief and drunk.

When Satampra Zeiros and his companion in crime Tirouv Ompallios encounter a hideous guardian in the temple of the toad god in the ruined old capital of Commoriom, he mentions that the creature gave “evidence of anthropophagic inclinations” and therefore their “departure” became “most imperative.” This is the way an unreliable narrator tells you that he saw a man-eating monster and got the hell out of there.

Satampra Zeiros himself achieved a rare distinction among Smith’s characters: he came back for a sequel. The one-handed thief would again tell of his adventures in the last Hyperborean story, “The Theft of the Thirty-Nine Girdles.”

“The Door to Saturn”

“The Door to Saturn”

Completed July 1930. First published in Strange Tales, January 1932.

Weird Tales editor Farnsworth Wright rejected this, one of the most bizarre of all Hyperborea stories, but Smith found a home for it in Clayton Publications’ better paying (but short-lived) rival, Strange Tales. The story must have caused some Wright real head-scratching; “Satampra Zeiros” contains ironic humor but still tells a conventional horror story. The “The Door to Saturn,” however, is a lengthy ‘punch line’ piece filled with comic-tinged oddness and jaw-busting alien names. It has more in common with the satirical fantasies of James Branch Cabell than anything that appeared in Weird Tales.

Very little of the story takes place in Hyperborea proper, but instead on the planet Cykranosh. The reader meets for the first time the frequently referenced sorcerer Eibon, who worships and receives favor from Tsathoggua (here spelled Zhothaqqua). When the inquisition of the elk-goddess Yhoundeh comes to seize Eibon for his heresies in his tower in far northern Mhu Thulan, the sorcerer escapes through a panel that takes him to Cykranosh, the planet where Tsathoggua once dwelt. The high priest of Yhoundeh, Morghi, follows after Eibon, and the two enemies team-up to survive among the weird peoples of Cykranosh while Morghi seeks to deliver a sacred phrase he learned from one of Tsathoggua’s ‘relatives.’ Ultimately, the set-up exists to deliver a twist finale that mocks the pretensions of religious quests. Smith would repeat this ‘set-up/punch line’ structure again in the even more effective “The Seven Geases.”

As the story’s title makes clear, Cykranosh is nominally Saturn. But the world on which Eibon and Morghi find themselves has more in common with H. G. Wells’ fantastic vision of life on the moon in The First Men in the Moon, Frank L. Baum’s Oz, and the setting of Bob Clampett’s surreal animated short “Porky in Wackyland.” The list of alien creatures comes with knowing, eye-winking ludicrousness.

“The Testament of Athammaus”

“The Testament of Athammaus”

Completed February 1931. First published in Weird Tales, October 1932.

Through another first-person account, this one from Athammaus, head executioner of the capital of Hyperborea, we hear about a central event in the history of the continent: the sudden abandonment of the capital Commoriom. When the execution of highwayman Knygathin Zhaum goes strangely wrong, the bizarre killer’s old ancestry to Tsathoggua starts to manifest itself. One execution after another cannot keep Knygathin Zhaum dead, and all of Commoriom soon suffers from the condemned man’s disturbing transformation.

The mordant humor of much of the Hyperborean cycle ebbs lower in this story. Athammaus does not have Satampra Zeiros’ picaresque sense of irony, but the hideous situation does have an absurd comedy to it, and Athammaus’ pride in his skills as an executioner make for amusing comments about the one execution that simply will not go the way it should. However, “The Testament of Athammaus” works mostly as horror, and Smith’s ornate writing reaches superb heights as Knygathin Zhaum turns less and less human; Smith visualizes the serpentine and mottled appearance of the creature, even in its more anthropoid stage, with loathsome delight. In a letter to H. P. Lovecraft in 1931, he expressed his satisfaction with the story, and commented that he thought Knygathin Zhaum was his best monster yet. But it still took two tries to get the story into Weird Tales, and it has seen few reprints since despite its quality and centrality to Hyperborean history.

“The Weird of Avoosl Wuthoqquan”

“The Weird of Avoosl Wuthoqquan”

Completed November 1931. First published in Weird Tales, June 1932.

This is the only Hyperborean story that Farnsworth Wright bought for Weird Tales on first submission. Smith himself had no great love for it, calling it “filler,” and it served as back-page material in the magazine. However, it has seen multiple reprints, probably because, as the shortest of the stories in the cycle, it fits easily into anthologies.

The story falls in a horror subcategory familiar to readers of E. C. Comics’ Tales from the Crypt or anthology television shows: a hateful, unlikable individual gets a gruesome but appropriate comeuppance. Greedy money-lender Avoosl Wuthoqquan of Commoriom receives a curse from a beggar, and the curse comes true when Avoosl Wuthoqquan’s avaricious pursuit of two magical gems leads him into the lair of a Tsathoggua-esque monster with a snide sense of humor. There is little else to the story, which has an adequate amount of strange descriptions and sly irony (particularly in the matter-of-fact final sentence), but nothing otherwise noteworthy or memorable.

The title requires an explanation for modern readers. “Weird” used as a noun has no connection to the adjective meaning ‘strange.’ It derives from the Old English and Scandinavian word wyrd or werde, meaning fate or destiny. An author less interested in painting a picture of an archaic world would have named the story “The Strange Fate of the Money-Lender.”

“Ubbo-Sathla”

“Ubbo-Sathla”

Completed February 1932. First published in Weird Tales, July 1933.

In his “Black Book,” where he kept a record of his writings, Clark Ashton Smith listed this story as part of The Book of Hyperborea, even though it only marginally touches on the ancient continent and begins and ends in contemporary London. It also contains none of the humor of the Hyperborean stories; Smith attempts to duplicate the style and structure of H. P. Lovecraft, and succeeds. Like many of Lovecraft’s stories, the protagonist of “Ubbo-Sathla” is an antiquarian on a quest for greater occult knowledge. He stumbles upon something ‘Man Was Not Meant to Know,’ and his fate remains nebulous in an epilogue tacked on the end. The short piece may fit poorly with the rest of the Hyperborean cycle, but “Ubbo-Sathla” makes for a first-rate Clark Ashton Smith plunge into the primordial.

The antiquarian in this case is Paul Tregardis, anthropology student and occult enthusiast, who has obtained a copy of the French translation of The Book of Eibon. In a curio shop in London he finds a mysterious rock unearthed in Greenland and believes he has located the magic stone that Hyperborean sorcerer Zon Mezzalamech used to peer back into the beginnings of earth to discover tablets of wisdom. Like a Lovecraft character, Paul Tregardis feels a fateful pull to stare into the stone and repeat the magic of Zon Mezzalamech to see back to the ultimate beginning and behold Ubbo-Sathla, the source of all terrestrial life.

Ubbo-Sathla, a primal bio-blob from which all other life eventually splits away and evolves, is another of Clark Ashton Smith’s important contributions to the Mythos. Ironically, Smith’s conception of Ubbo-Sathla does not deviate far from what some biologists now theorize about the origins of life on our planet. But where a scientist would marvel at the wonder of such a primordial creature, both author and character behold it with horror:

There, in the grey beginning of Earth, the formless mass that was Ubbo-Sathla reposed amid the slime and the vapors. Headless, without organs or members, it sloughed from its oozy sides, in a slow, ceaseless wave, the amoebic forms that were the archetypes of earthly life. Horrible it was, if there had been aught to apprehend the horror; and loathsome, if there had been any to feel loathing. About it, prone or tilted in the mire, there lay the mighty tablets of star-quarried stone that were writ with the inconceivable wisdom of the pre-mundane gods.

Here Clark Ashton Smith gambols in the black fields of H. P. Lovecraft, turning the old supernatural horrors into something cosmic, scientific, and yet even less comprehensible and dreadful than before.

“The Ice Demon”

“The Ice Demon”

Completed July 1932. First published in Weird Tales, April 1933.

The three “Ice Doom” stories, following close upon each other, bring the reader toward the eventual doom of Hyperborea beneath the advancing glaciers. This mini-cycle differs from the rest of the series: humorless and seeming to imitate Smith’s two other fantasy worlds, Averoigne and Zothique.

“The Ice Demon” probably occurs chronologically last in the series. The glacier of Polarion has pushed far south over the continent, crushing out all of Mhu Thulan. The King of the Northern city of Iqqua vanishes with his wizard when they try to halt the marching glacier. Years later, a hunter-trader named Quanga takes two jewelers onto the glacier to find the icy tomb of the King and retrieve his jewels. Clark Ashton Smith brings down upon the hapless thieves the ‘soul’ of the glacier, anthropomorphizing the frigid death of Hyperborea as a malign entity.

As a straightforward horror story of hallucination amidst encroaching death, “The Ice Demon” works well. Its theme of a dying civilization and its bleak loneliness makes it akin to the Zothique stories; perhaps Smith changed the tone to make this Hyperborean entry an easier sell to Weird Tales. The story’s language is also more direct and less ornate than customary for Hyperborea, but nonetheless Smith achieves the portraiture of the glacier as an intelligent force with his usual skill.

Fans of Robert E. Howard will notice a similarity between this story and the early Conan tale “The Frost-Giant’s Daughter.” Both contain astonishing dashes across arctic landscapes that have twisted into unreal worlds. The two authors wrote their stories roughly around the same time, so a direct connection seems unlikely, but the similarities nonetheless show the influence that Smith’s style had on other writers in the Weird Tales circle.

“The White Sybil”

Completed November 1932. First published in Science & Fantasy Book No. One (1934).

The end starts with the beginning, when Commoriom still stands and the glacier of Polarion has yet to advance across Mhu Thulan. Then the White Sybil appears, a fleeting beautiful presence whose lips bring word of the doom to come — not only to opulent Commoriom, but to all of Hyperborea. The young man Tortha falls under the trance of the alluring Sybil and follows her up into the glaciers, where he will receive a vision of the fate of the land. The concept sounds like a grand way to bring the Hyperborean cycle full circle, and the disillusioned romance holds promise, but “The White Sybil” feels like Smith should have spent greater time and detail on it. It reads like a sketch, and compared to the similar “The Ice Demon,” its transcendent, dream-like world has meager poetic effect. Understandably, Smith never managed to sell this story to a professional market, and it made its first appearance in a non-paying fanzine.

“The Coming of the White Worm”

“The Coming of the White Worm”

Completed September 1933. First published in Stirring Science Stories, April 1941, in an abridged version.

Smith unleashed a last “serious” story of the northern continent before returning to his “grotesque ironies.” “The Coming of the White Worm” contains some of the densest, most archaic prose that Smith ever wrote. Smith frames the story as Chapter IX of the fictitious Book of Eibon, from a translation by Gaspard du Nord, the hero of the Averoigne tale “The Colossus of Ylourgne.” This device explains the complexity of the story’s diction, Byzantine even considering the author’s usual style. This poetic language made the story a difficult sell to the pulps. Eight years after writing it, Smith managed to sell “The Coming of the White Worm” to Stirring Science Stories, a short-lived pulp from tiny Albing Publications. Like its sister publication, Stirring Detective and Western Stories, the magazine survived for only four issues. Smith had to pare down many of his more oblique words to make the sale. The original version, which didn’t see print until 1989, begins:

Evagh the Warlock, dwelling beside the boreal sea, was aware of many strange and untimely portents in mid-summer. Frorely burned the sun above Mhu Thulan from a welkin clear and wannish as ice. At eve the aurora was hung from zenith to earth, like an arras in a high chamber of gods.

The abridgement removes the obscure words to create a more readable but less effective version:

Evagh the Warlock, dwelling beside the boreal sea, was aware of many strange and untimely portents in midsummer. Chilly burned the sun above Mhu Thulan from a heaven clear and pallid as ice. At eve the aurora was hung from zenith to earth like an arras in a high chamber of the gods.

The abridgement also changes some of the archaic inflections, such as “he who slayeth” to “he who slays.”

The events of the story, however, are identical in both versions. The sorcerer Evagh, living in Mhu Thulan during balmier days, witnesses the advent of a mobile iceberg that slays with a magical cold. The hideous white worm Rlim Shaikorth moves Evagh and his castle onto the iceberg to join other captive wizards as its servants. When the other wizards begin to vanish one by one, Evagh starts to suspect Rlim Shaikorth’s true reasons for needing servants.

Smith considered “The Coming of White Worm” a direct contribution to Lovecraft’s Mythos, but again the differences between the two men’s methods of examining extraterrestrial deities are startling. Smith does not leaven Lovecraft’s cosmic terrors with a soupçon of comedy as he does with the stories featuring Tsathoggua. Smith’s focuses instead on the entity, Rlim Shaikorth, as a fearsome personality who dictates to its followers like a grim Norse god. If Tsathoggua has a Greek pantheon influence, then Rlim Shaikorth belongs to the chilly world of the Teutonic gods.

Although it occurs in the early days of Hyperborea, the frigid whisper of the doom of Hyperborea blows through the story. It feels as if Smith was trying to make up for the flaws of the two ‘Ice Doom’ stories that preceded it. If so, he succeeds: “The Coming of the White Worm” remains one of the most frequently reprinted of all the Hyperborean stories and a superb piece of word-sorcery.

“The Seven Geases”

“The Seven Geases”

Completed October 1933. First published in Weird Tales, October 1934.

The term “geases,” like Avoosl Wuthoqquan’s “weird,” requires explanation. The Celtic word geas (pronounced gesch) means a magical compulsion, binding, or taboo, such as forcing a hero to go on a quest or prohibiting him from taking specific actions. In Celtic myths, a hero can receive a geas from a sorcerer, a king, or his parents, but most frequently from witches or hags whose path he crosses.

“The Seven Geases” has no plot in the traditional sense. Its structure compares best to that of a joke: a similar situation repeats over and over until a punch line flips around the understanding of all that has occurred before…or in this case, negates it with the written equivalent of a rim-shot punctuating a stand-up comedian’s bad joke. Ralibar Vooz, a noble of Commoriom and an expert hunter, makes an expedition into the Eiglophian Mountains to hunt the subhuman Voormis. But when he interrupts the magical ceremony of the wizard Ezdagor, the enraged magician casts a geas on Ralibar Vooz to send him deep under Mount Voormithadreth to the lair of Tsathoggua. Tsathoggua has no use for the hunter, so he sends him to spider-god Atlacha-Nacha. Who sends him to the inhuman sorcerer Haon-Dor. Who sends him to…

Farnsworth Wright initially rejected the story as “one geas after another,” but that is exactly the point. Ralibar Vooz’s wanderings deeper and deeper into the subterranean realms beneath the Eiglophians and his encounters with foul gods and lost races resemble not so much a story as a amusement park dark ride. Smith has a joyous time with the parade of grotesques; he often noted this story as one of his favorites. The humorous ironies are often hysterical: the rational Serpent Men dismiss Ralibar Vooz because there is “no place for [him] in our economy,” and a horde of non-corporeal dinosaurs make multiple attempts to eat the cursed man but can’t keep him inside their bodies. The crowning gag of “The Seven Geases” comes in its last paragraph. This punch line brings the story to the only conclusion it could really arrive at-even if it isn’t actually a conclusion at all.

Despite the satiric tone and playful horrors, “The Seven Geases” has much in common with the themes of H. P. Lovecraft’s Mythos. As in Lovecraft’s stories, humans here are nothing more than insignificant pawns to vast, uncaring powers. Life looks like a cosmic joke, ending either at the whim of vicious, uncaring deities, or at the whim of a random and capricious universe.

“The Theft of the Thirty-Nine Girdles”

“The Theft of the Thirty-Nine Girdles”

Completed April 1957. First published in Saturn Science Fiction & Fantasy, March 1958.

Lack of success with the Hyperborean stories led Smith to stop writing them in 1933 and turn his energies to the more successful Zothique series. He went back to Hyperborea only once more, during his last phase of writing in the late 1950s. Appropriately, he returned to the character who started the cycle in the first place, loquacious thief Satampra Zeiros. The comic rogue recounts how he and his beautiful partner Vixeela tried to steal the thirty-nine bejeweled chastity girdles from the temple of the Moon God Leniqua in Uzuldaroum. Satampra Zeiros again drenches his language with smirking irony, such as claiming that he always “endeavored to serve merely as an agent in the rightful redistribution of wealth.” However, the story is a disappointment. It reads too dryly, and Smith seems to have scant interest in what happens. Nothing surprising or particularly fantastic occurs, and the conclusion feels abrupt and unsatisfying.

Fragments and Synopses

One of the mysteries of the Hyperborean stories is the ‘loss’ of one work, “The Voyage of King Euvoran,” to the Zothique series. Smith planned the story as a Hyperborean one filled with sardonic humor, but his obsession with Zothique turned the story into one of that far future continent-with the Hyperborean comedy intact. The story saw print in shortened form as “The Quest of the Gazolba” in Weird Tales in 1946. Smith presented his preferred version in his self-published pamphlet, The Double Shadow and Other Fantasies (Auburn Journal, 1933). This version also takes place in Zothique, so most likely Smith never finished the Hyperborean version.

The lengthiest fragment to survive is the fascinating “The House of Haon-Dor.” Smith includes the story in his list of entries in The Book of Hyperborea, but it has only a marginal connection to rest of the series since it takes place in the contemporary California Sierras. The fragment introduces Robert Faraway, a youth exploring an old hydraulic mining site who becomes fascinated with a strange abandoned cabin. The surviving synopsis continues the story, where the Hyperborean wizard Haon-Dor (encountered in “The Seven Geases”) possesses Faraway with a vampiric spirit. The fragment shows that Smith had considerable skill describing his own physical world (Northern California), and his prose portrait of the lonely hydraulic mining site remains a potent one. Unfortunately, the illness of Smith’s parents caused him to abandon this story, which had the potential to mix together the two worlds in which he lived: his real one and his literary one.

A few other brief synopsis survive: “The Hyperborean City” and another adventure of Satampra Zeiros called “The Shadow from the Sarcophagus,” and a handful of poems. After this, Hyperborea at last falls silent beneath the silencing ice.

Postscript

Postscript

The Hyperborea series is more ‘difficult’ than Smith’s other fantasy cycles; its tone varies more than the single-minded bleakness of Zothique, and its setting is bizarre compared to the mundane medieval Averoigne. But no other of Smith’s works has had such an unusual medley of elements, with Lovecraftian themes rubbing against satiric jabs, elevated mocking language, black jokes, and a sense of a slow, chilly annihilation that cannot be escaped.

With all the fears of climatic global climate changes caused by environmental abuses, could we perhaps one day turn into the new Hyperboreans? A decadent culture with near-magical abilities that vanished beneath an unstoppable advance of ice?

I wouldn’t worry too much about it. Remember the words on the newly discovered tablets of the scribe J’oh Struh-mah:

An Ice Age is coming

But I have no fear

‘Cause Hyperborea is freezing

And I, I live by Mu Thulan.”

You can read Part I in this series, “Averoigne,” here, Part III in the series, “Tales of Zothique,” here, and Part IV in the series, “Poseidonis, Mars, and Xiccarph,” here.

Our recent coverage of Clark Ashton Smith includes:

New Treasures: The End of the Story: The Collected Fantasies, Vol. 1 by Clark Ashton Smith

Vintage Treasures: The Timescape Clark Ashton Smith

The Shade of Klarkash-Ton by James Maliszewski

One Shot, One Story: Clark Ashton Smith by Thomas Parker

New Treasures: The Dark Eidolon and Other Fantasies by Clark Ashton Smith

The Crawling Horrors of Mars: Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis”

Deepest, Darkest Eden edited by Cody Goodfellow by Fletcher Vredenburgh

Adventures in Stealth Publishing: The Return of the Sorcerer

A Few Words on Clark Ashton Smith by Matthew David Surridge

The Unqualified Unique: The Daily Mail Interviews Me for Clark Ashton Smith’s 50th Morbid Anniversary by Ryan Harvey

Of Secret Worlds Incredible: A Psychedelic Journey into Clark Ashton Smith’s Poetic Masterpiece by John R. Fultz

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part I: The Averoigne Chronicles by Ryan Harvey

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part II: The Book of Hyperborea by Ryan Harvey

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part III: Tales of Zothique by Ryan Harvey

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part IV: Poseidonis, Mars, and Xiccarph by Ryan Harvey

8 thoughts on “The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith PART II: The Book of Hyperborea”