Adventure On the Page: Genre Fiction vs. Joyce Carol Oates

The more I write, the more opprobrium I feel for categorical definitions of fiction, notably “genre fiction” and “literary fiction.” I like to think I practice both, and that most readers read both. Crazier still –– lunacy, truly –– I suffer the apparent delusion that often the two categories cannot be separated, except by book vendors aiming to simplify or streamline the shopping experience.

The more I write, the more opprobrium I feel for categorical definitions of fiction, notably “genre fiction” and “literary fiction.” I like to think I practice both, and that most readers read both. Crazier still –– lunacy, truly –– I suffer the apparent delusion that often the two categories cannot be separated, except by book vendors aiming to simplify or streamline the shopping experience.

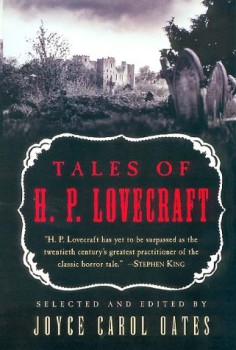

Not long ago, I delved back into Joyce Carol Oates’s introduction to a delicious anthology, Tales of H.P. Lovecraft, and I came across this passage:

However plot-ridden, fantastical or absurd, populated by whatever pseudo-characters, genre fiction is always resolved, while literary fiction makes no such promises; there is no contract between reader and writer for, in theory at least, each work of literary fiction is original, and, in essence, “about” its own language; anything can happen, or, upon occasion, nothing.

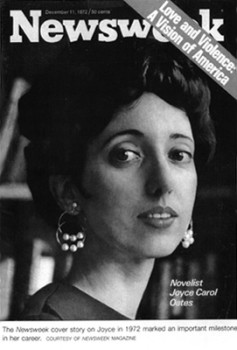

Now –– and I say this as a long-time and self-avowed fan of your work, Ms. Oates –– them’s fightin’ words.

Oates’s many virtues have been extolled on Black Gate’s pages before. (Two examples may be found HERE and HERE.) Suffice it to say that stories like “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been” and “Theft,” not to mention novels such as We Were the Mulvaneys, need no defense. Oates is a master of the fictional form, full stop.

But does her statement, above, hold water?

In the soggy bottomland backwater where I cut my literary eyeteeth, it’s melodrama that always resolves. In a melodramatic play/film or story/novel, good triumphs, evil loses, and we take a moment to bask in that victory before the curtain (however metaphorical) comes down. Characters don’t exhibit divided natures and complexity is reserved for plot devices and/or various stages of jeopardy. Moral quagmires are limited or non-existent. The question of “How?” may be unsettled until the climax, but the outcome itself is a foregone conclusion. Indiana Jones (to cite one filmic example) will save the day, period. The hero of a British panto will always outwit the mustachioed, cape-wearing villain, and Enid Blyton’s various child-heroes will forever defeat the clumsy smugglers who threaten to ruin the plucky tots’ summer vacation.

In the soggy bottomland backwater where I cut my literary eyeteeth, it’s melodrama that always resolves. In a melodramatic play/film or story/novel, good triumphs, evil loses, and we take a moment to bask in that victory before the curtain (however metaphorical) comes down. Characters don’t exhibit divided natures and complexity is reserved for plot devices and/or various stages of jeopardy. Moral quagmires are limited or non-existent. The question of “How?” may be unsettled until the climax, but the outcome itself is a foregone conclusion. Indiana Jones (to cite one filmic example) will save the day, period. The hero of a British panto will always outwit the mustachioed, cape-wearing villain, and Enid Blyton’s various child-heroes will forever defeat the clumsy smugglers who threaten to ruin the plucky tots’ summer vacation.

“Genre,” as I understand the term, is a post facto appendage, a tag employed to assign a piece of work its particular place in the mind or on the shelf. A good many genres exist, that’s certain, and among them (for better or for worse) are Mystery, Thriller, Fantasy, Science Fiction, and Romance. All of these can be broken down further: Cozy Mysteries, Sword and Sorcery, Paranormal Romance. (My favorite of these sub-categories has to be the “Bodice-Ripper,” in which we must assume the characters are always in a great hurry when it comes to the final [shall we say] denouement.)

Even more troubling is the genre division known as African-American Literature, to say nothing of Gay and Lesbian Lit. If we agree with the maintenance of such divisions, then we must also ask, at what point do we balkanize all human experience and reduce our personal selection of books to those that mirror only our own lives? Is it desirable to have a genre labeled “Me”?

Mysteries do indeed tend to wrap themselves up with a bow. The detective (of whatever sort) brings order to a disordered world and the balance is restored. Thrillers tend to do much the same. But note the word “tend.” Sherlock Holmes loses his life in attempting to right the world, and the cost to the cosmos is uncertain at best. In The French Connection (1971), which may look like a disposable if well-made buddy picture, one of our supposed heroes winds up shooting his partner while the bad guy escapes. Where does that fall in the pantheon of clear resolution and how can the reader or viewer not help but feel a bit cheated –– or, at the very least, stunned?

to a disordered world and the balance is restored. Thrillers tend to do much the same. But note the word “tend.” Sherlock Holmes loses his life in attempting to right the world, and the cost to the cosmos is uncertain at best. In The French Connection (1971), which may look like a disposable if well-made buddy picture, one of our supposed heroes winds up shooting his partner while the bad guy escapes. Where does that fall in the pantheon of clear resolution and how can the reader or viewer not help but feel a bit cheated –– or, at the very least, stunned?

If we follow the Prince With the Black Sword through to his final adventure, we discover resolution of a kind –– but surely not the sort we expected or want. Moorcock violates our mutual contract in the most egregious way.

Literary historians credit Edgar Allen Poe with virtually inventing the detective story, and with it, the entire mystery field. Yet mystery has always existed; it’s inherent in mortal existence and the theme crops up throughout our written legacy. Oedipus seeks to know why the gods are displeased with his reign and sets out to unmask the truth. Hamlet (via a ghost, no less) discovers that something is rotten in Denmark and endeavors to learn from whence comes that noxious stench.

Oates insists that the author/reader contract in genre fiction must play out as expected, i.e., the work must reach a satisfying and predictable conclusion. I don’t deny that’s the pattern, but I strenuously object to the notion that such an apple cart cannot be upended.

Oates insists that the author/reader contract in genre fiction must play out as expected, i.e., the work must reach a satisfying and predictable conclusion. I don’t deny that’s the pattern, but I strenuously object to the notion that such an apple cart cannot be upended.

Consider Karen Russell’s “Vampires In the Lemon Grove,” which I foisted on my Writing 205 class here at Harlaxton College just a few weeks back. Russell introduces trope after vampiric trope, only to knock them down, one by one, after which this very adept, very successful author has the gall SPOILER SPOILER SPOILER SPOILER to kill off our supposedly immortal hero. As to how he became a vampire, which is usually ground zero for such fictional tales, fuggedaboutit. Russell makes it clear that she doesn’t care and neither should we.

So what is “Vampires In the Lemon Grove,” if not a quite deliberate nose-thumbing at literary convention?

Consider John Crowley’s Little, Big, which I explored in February of this year. My local library files it under “Fiction,” not “Fantasy,” but the darn thing has actual fairies, for goodness’ sake, plus a shape-shifting stork (it delivers babies, don’t you know). Most importantly, though its plot is dense and intertwined, and though its prose is lyrical and gorgeously expressive, Little, Big does indeed resolve. It obeys the contract that Oates insists belongs to genre.

Lovecraft himself might illuminate the dilemma and shed light on a solution. In one of his many essays, In Defense of Dagon (quoted by Oates), Lovecraft writes that, “a tale should be plausible –– even a bizarre tale except for the single element where supernaturalism is involved.”

This opens the door wide for writers of myriad goals to employ accepted, lauded, and canonized literary techniques in the service of stories that deal headlong with the imaginative and fantastic. Crowley and Russell fit the bill. So do thousands of others, hopefully including myself.

What these stories need not do is grovel at the foot of expectations.

In the meantime, we live witness to an ongoing turf war driven by publishers (also advertisers) between broad categorization and an individual writer’s creative identity. I don’t expect to see a winner declared any time soon, but I look forward to a continued blending of form. Out of that tension, we will get fresh new masterworks, and I cannot wait to read each and every one, no matter where they get filed on our shelves, digital or otherwise.

broad categorization and an individual writer’s creative identity. I don’t expect to see a winner declared any time soon, but I look forward to a continued blending of form. Out of that tension, we will get fresh new masterworks, and I cannot wait to read each and every one, no matter where they get filed on our shelves, digital or otherwise.

As a final note, I cannot resist mentioning Craig Wright’s grim post-9/11 play, Recent Tragic Events, in which Joyce Carol Oates makes an extended cameo appearance –– not as herself, but as a sock puppet. She gives voice to a character (Nancy) otherwise silenced by the fall of the World Trade Center. Did Oates approve? I suspect, given her self-professed interest in women who have survived and remade themselves after suffering trauma, that she enjoyed the send-up very much.

But is it literature? Or “merely” “genre”?

‘Til next time.

Dream hard.

Write harder.

Onward.

Mark Rigney has published three stories in the Black Gate Online Fiction library: ”The Trade,” “The Find,” and “The Keystone.” Tangent called the tales “Reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… once I started reading, I couldn’t stop. I highly recommend the complete trilogy.” In other work, Rigney is the author of “The Skates,” and its haunted sequels, “Sleeping Bear,” and Check-Out Time, forthcoming in 2014.

Sometime after publishing his zombie novel Zone One, mainstream author Colson Whitehead said he’d rather shoot himself in the face than have another conversation about genre vs ‘literary’ fiction. I feel the same way, yet here I am.

Oates’ comments quoted in this article are the same old nonsense that gets spouted periodically by mainstream writers. I wouldn’t necessarily expect such comments from Oates, though, as she has shown an affinity for genre fiction throughout her career: she’s written gothic and mystery novels, she edited that Lovecraft volume, she’s contributed to horror anthologies, etc. And yet I guess she’s still to an extent part of the mainstream old guard that vigorously defends borders real or imagined.

Fortunately more and more mainstream authors now seem to ‘get’ genre fiction, such as Michael Chabon, Jonathan Lethem (whose roots are in SF), and Junot Diaz.

Golgonooza – I know how Mr. Whitehead feels.

And yes, I’ve certainly covered this ground on BG a few times now. But I don’t mind as much as Mr. Whitehead, in part perhaps because of my background in retail books. I’m fascinated by the division and enjoy unpacking it.

I agree with you about Chabon, Lethem, and Diaz. And (fortunately) many more!

Well, I tend to agree with you, Mark (and I’m glad you enjoyed Little, Big!). I wonder if there was any more context to that quote? I’m specifically curious by what she meant by ‘resolved.’ At it’s broadest, maybe the quote could just mean that ‘genre’ literature has to have some positive identifiable quality that establishes it as ‘genre.’ Whereas ‘literary’ fiction doesn’t mean much, because each individual work is ‘literary’ in its own way.

I dunno, I’m grasping here.

Who was it that said every book has a genre, if only a genre of one? I know it was Northrop Frye who said that “The very word ‘genre’ sticks out in an English sentence as the unpronounceable and alien thing it is” …

Matthew – the quote is part of a multi-page and very generous intro to the Lovecraft tome. It’s not taken out of context here (I can’t stand it when people do that); in fact, it’s fairly self-contained. I will say this: it’s certainly not her main point in an essay intended to place Lovecraft in history and suggest his strengths and weaknesses while very definitely celebrating his achievements.

I wonder if tweets are each literary in their own way? Eegads, I can’t believe I said that.

Yeah, sorry, I didn’t mean to imply that you weren’t telling the whole story. It just seems so odd coming from Oates, and I was wondering basically where she was at (with respect to genre) that she’d write this. The book was published in 2001, right? So that’s not even that long ago. Odd.

Matthew – no worries at all! You’re right to wonder. And it IS odd to hear, coming from her.

The main thing is, you handed me LITTLE, BIG.

Forever indebted.

Mark

This discussion reminded me of something that I think William Shatner once said, expressing his disdain for genre division: he wished a reader could walk into a bookstore and discover his TekWar novels filed next to Shakespeare.

That’s funny, and I do see his broader point (it would introduce readers to new genres that they might not otherwise discover if they only frequent certain narrow sections). There can be great reward in going into a book or a film not having preconceived notions of what is going to unfold.

At the same time, genre categorizations do serve a very valid purpose. When I get finished reading and enjoying a particular type of book and want another of that kind, I can go to the appropriate shelf to find works that somebody considered categorically similar. Surprises can be great, but most of the time when we go out to eat we choose the restaurant and the item from the menu based on what we are having a craving for.

That said, when I read Oates’s introduction to the Lovecraft volume a few years back I had the same reaction you did: I don’t think it’s a valid or sensible distinction.

Nick – I do agree that categories in and of themselves can serve, as you put it, a valid purpose. We humans like repetition; we crave the (good) experience we had last time. And of course we must have some sort of filing system — for everything from paperwork to metaphysics, from stamp collecting to how to (safely) cook supper.

My worries are all about ossification. Ruts. The habitual blinders that prevent our search for good books (or, to borrow from Viktor Frankl, “meaning”) from ranging beyond what’s already at our fingertips.

But of course I’m conflicted. Shakespeare and Shatner, side by side? Zoinks!

[…] Adventure On the Page: Genre Fiction vs. Joyce Carol Oates […]