Affair of the Bear: The Oakdale Affair by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Yes, this is the 3,000th post on Black Gate. Discovered after the fact, of course. Never thought I’d be writing about a murder mystery centered on a bear for the occasion, but what the hey.

Yes, this is the 3,000th post on Black Gate. Discovered after the fact, of course. Never thought I’d be writing about a murder mystery centered on a bear for the occasion, but what the hey.

In the spring of 1917, as he was completing the last of the “New Tarzan Adventures” that would eventually fill the volume Jungle Tales of Tarzan, Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote a short novel (40,000 words) titled “Bridge and the Oskaloosa Kid.” A reader of the previous year’s The Return of the Mucker might recognize the name “Bridge” as belonging to that novel’s itinerant poet and co-hero. Burroughs liked the character so much that he spun him off into his own story: a crime drama/mystery, something different for the author.

Editor Bob Davis at All-Story found little to appreciate about ERB’s new tact when “Bridge and the Oskaloosa Kid” landed on his desk. He argued that its twist ending stretched credulity past what readers would tolerate: “Lord! Edgar, how do you expect people who love and worship you to stand up for anything like that? And the bear stuff, and the clanking of chains!” Davis may also have objected to mentions of one of the villains injecting morphine to feed an addiction. Although Davis remarked that Bridge was a “splendid character” in The Return of the Mucker and “well worth a great story,” the editor didn’t think this was it. He bounced the novel back to ERB.

Burroughs had his own doubts about “Bridge and the Oskaloosa Kid,” criticizing his performance as “rotten” even before he finished. But his name was still good for a sale in a magazine in 1917, and the novel ended up at Blue Book, printed in full in the March 1918 issue under the more economical title The Oakdale Affair. Editor Ray Long paid $600 for it, considerably less than ERB’s standard pay-rate at the time.

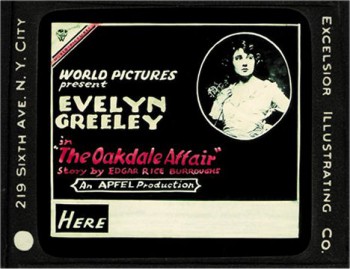

A year later, a movie titled The Oakdale Affair starring Evelyn Greeley premiered from World Film Company. It was the fourth film made from ERB’s work, and a rare non-Tarzan one. Somebody must have liked the book, the opinions of the author and his editor be damned!

What to make of this unofficial third novel of the “Mucker Trilogy,” a crime thriller/mystery with a vanished heiress, murderous drifters, gypsies, an enthusiastic child detective, a deadly bear, a lynch mob, a couple of dead bodies, and a chain-clanking ghost in a haunted house? Did ERB stray too far in looking for somewhere else for his poetry-loving Bridge to roam?

No, he didn’t. But he should have. He should have strayed much farther. Despite bringing along one of his most fascinating characters, Burroughs turned out a middle-of-the-road crime melodrama restricted to the sleepy environs of the title town. The Oakdale Affair offers few of the extravagances that made the author famous, and following up the boisterous “Mucker” duology, it feels too cramped. Burroughs isn’t adept with the murder mystery aspect of the story, and is more comfortable with the chase formula, although the chase is limited. Burroughs’s prose flows fast, as it does in most of his work from the ‘teens; outside of the over-worked slang that taints most popular novels of this era, the writing is unforced. Even if the story doesn’t succeed fully in its chosen genre, the writing carries it forward. But the only place where it really soars is during a gothic episode involving a supposedly haunted house and a hideous chain-clanking “thing” inside.

Although I think it’s impossible to spoil an Edgar Rice Burroughs novel since he works less on the level of surprise and more in the arena of imagination and pacing, The Oakdale Affair is partially a mystery melodrama, so I’ll alert readers to the section below containing details about the last quarter of the book.

In the doubly-fictional town of Oakdale (“oh, let’s call it Oakdale,” the narrator mutters on page one), fiendish things are afoot. Over the course of one night, Abigail Prim, the daughter of wealthy bank owner Jonas Prim, vanishes from the train carrying her to her fiancé; a thief breaks into the Prims’ mansion and makes off with their daughter’s jewelry; an unknown assailant beats the local miser Old John Baggs to death; and man-about-town Reginald Paynter is found dead in a ditch at the side of the road, his skull crushed.

In the doubly-fictional town of Oakdale (“oh, let’s call it Oakdale,” the narrator mutters on page one), fiendish things are afoot. Over the course of one night, Abigail Prim, the daughter of wealthy bank owner Jonas Prim, vanishes from the train carrying her to her fiancé; a thief breaks into the Prims’ mansion and makes off with their daughter’s jewelry; an unknown assailant beats the local miser Old John Baggs to death; and man-about-town Reginald Paynter is found dead in a ditch at the side of the road, his skull crushed.

Readers know the answer to one of the mysteries, since the book opens on the burglar sneaking into the Prim mansion. The thief is a young man, almost a boy, who has taken on the sobriquet “the Oskaloosa Kid,” which belongs to an older, infamous criminal. After escaping from the house, the Kid runs into a group of drifters led by the villainous “Sky Pilot.” His gang of vagabonds includes fellows with such colorful names as Soup Face, Dopey Charlie (the morphine addict), the General, Dirty Eddie, and Columbus Blackie. The gang tries to kill the Kid that night and take his spoils. The Kid flees from them and runs into none other than… Bridge.

Bridge is still wandering and still quoting poetry by H. H. Knibbs. He comes to the aid of the Oskaloosa Kid, who is clearly out of his depth, and for the rest of the story they move through escapes and tight corners to elude Sky Pilot’s killer gang and the police led by Detective Burton. They also pick up a panicked girl who refuses to tell them her name, but apparently knows something about the murder of Reginald Paynter.

Also in the mix: Willie Case, a pesky kid who tries to turn amateur sleuth to help Burton track down the fugitives; a horrible creature with clanking chains who traps our heroes (and some of the villains) inside the “haunted” old Squibb house; and Giova, a grieving gypsy girl with an ornery pet bear named Beppo.

The central drama isn’t figuring out who killed Paynter and Old Man Baggs, or what happened to the vanished Abigail Prim. It’s about Bridge’s relationship with the troubled youth to whom he’s hitched his fortune. Bridge — who has met the real Oskaloosa Kid before — immediately gets strange feelings from this boy pretending to be the notorious criminal:

What was the appeal… in the pseudo Oskaloosa Kid? He had scarce seen the boy’s face, yet the terrified figure had aroused within him, strongly, the protective instinct. Doubtless it was the call of youth and weakness which find, always, an answering reassurance in the strength of a strong man.

Bridge makes a few references to his early association with Billy Byrne to make the connection to “The Mucker” books solid. He thinks that “Not since he had followed the open road in company with Billy Byrne” has he felt such companionship as with the faux-Oskaloosa Kid. He also reminds Sky Pilot’s thugs about a minor incident in The Return of the Mucker with two road bandits — a moment even careful readers of that book may have forgotten.

But no amount of backlinks can disguise that Bridge is a lesser persona than when he was Billy Byrne’s poetry-spouting comrade in danger. He retains some of his sharp humor (“Before you hang us… would you mind explaining just what we’re being hanged for — it’s sort of comforting to know, you see.”) and still likes to quote H. H. Knibbs’s poetry, but far less than he did in the previous book. Readers unfamiliar with The Return of the Mucker will wonder what the poetry quotes are even about, since they have no connection to the plot and don’t appear often enough to develop as a character trait. It’s as if Burroughs no longer knew what to make of the poem-loving side of Bridge’s personality, and unfortunately that is a major part of his appeal.

But no amount of backlinks can disguise that Bridge is a lesser persona than when he was Billy Byrne’s poetry-spouting comrade in danger. He retains some of his sharp humor (“Before you hang us… would you mind explaining just what we’re being hanged for — it’s sort of comforting to know, you see.”) and still likes to quote H. H. Knibbs’s poetry, but far less than he did in the previous book. Readers unfamiliar with The Return of the Mucker will wonder what the poetry quotes are even about, since they have no connection to the plot and don’t appear often enough to develop as a character trait. It’s as if Burroughs no longer knew what to make of the poem-loving side of Bridge’s personality, and unfortunately that is a major part of his appeal.

Bridge upstages many characters in The Return of the Mucker, but here he’s occasionally upstaged by Willie Case, the snoopy kid who starts out as a minor annoying plot device (he points Detective Burton in the right direction), but eventually turns into an intriguing character in his own right. His fascination with being a detective and his solo-pursuit of Bridge and Co. becomes as exciting a quest as anything else. The vignette of him having a panic attack during his first trip to a restaurant to spend his reward money is a memorable passage, and rings true to the class-conscious ERB.

The main problem that Bridge faces in The Oakdale Affair is that the story forces him into the role of the main hero, where he was originally created as a supporting character. In The Return of the Mucker, he functions as a balance to Billy Byrne and guides the hero’s arc, but he gets lost in space in his own book with no one for him to orbit. His “partner” is the Oskaloosa Kid, who acts too passive for most of the book to give Bridge anything to do aside from wonder about the Kid’s oddness. Bridge has no specific reason to entangle himself in this Affaire d’Oakdale, trying to rescue the Kid and the terrified mystery girl; even he has to wonder at his choice:

…he let his mind revert to the events of the past twenty four hours and as he pondered each happening since he met the youth in the dark of the storm the preceding night he asked himself why he had cast his lot with these strangers. In his years of vagabondage Bridge had never crossed the invisible line which separates honest men from thieves and murderers and which, once crossed, may never be recrossed. Chance and necessity had thrown him often among such men and women; but he had never been one of them.

Now Bridge has gotten entangled in a situation that puts him “conniving in the escape of at least two people who might readily be under police suspicion.” He could have extricated himself from the situation earlier, so why didn’t he?

That explanation involves…

* * * Spoilers * * *

What did editor Bob Davis find so unbelievable about the manuscript of “Bridge and the Oskaloosa Kid”? In his own words from his rejection letter: “None of us can swallow the fact that the ‘Oskaloosa Kid’ is a pullet!” Yes, it turns out that the Oskaloosa Kid is Abigail Prim, the missing heiress, in boyish disguise.

I hope that when Davis wrote “none of us can swallow” this twist, he didn’t mean it was a surprise. Burroughs telegraphs the twist relentlessly. Bridge’s musings about the oddness of “the Kid” give away the game early, if readers didn’t already pick up on it when the Kid stumbles in her dialogue and almost reveals her gender, and later hatches lame excuses not to get out of her wet clothes. The “other girl,” who eventually explains that she’s the previously unmentioned character Hettie Penning, is so obviously manufactured as a red herring to make readers believe that she is Abigail Prim that she’s practically walking around with the words “I AM NOT ABIGAIL PRIM” stenciled on her forehead. Burroughs was a poor bluffer, a side effect of his boisterous writing style. This made him unsuited for mysteries, which he once commented didn’t have enough dead bodies for his taste. His late entry into the straight mystery genre, with the hilarious title “More Fun! More People Killed!”, never sold. (I don’t care about the quality of the story; that title should have sold instantly.)

The true identity of the Oskaloosa Kid has the unfortunate consequence of enfeebling his/her character. Too much emphasis is put on how “the Kid” is weak and helpless, squealing and whimpering and clutching her defender’s side, and how Bridge feels an impulse to protect “him” as if he were a woman. This type of quivering female was common for the pulps of the day, but it does not fit with a woman like Abigail who would flee from a hated engagement, dare to break into her parents’ home to steal her own jewels, and then go hang out with a pack of salacious-looking drifters. Burroughs must have felt it necessary to make Abigail act like a “pretty young thing” to excuse Bridge’s feelings toward her in boy-disguise without making readers of the time uncomfortable.

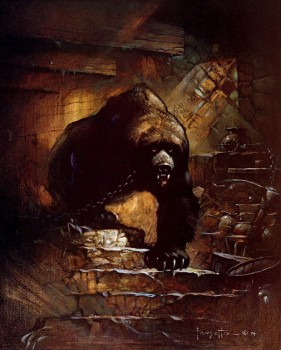

Oh… Beppo the Bear is the “monster” in the Squibb’s house dragging the chain and chasing intruders up stairs. Unlike Bob Davis, I have no issue with this. Beppo’s segments are the best in the book, and a ravenous bear roaming a crumbling old house is an easier gag to believe than Abigail Prim’s charade. When Beppo rips into the vagabond villains during the action climax, it’s the best rush of old-fashioned ERB excitement anywhere in The Oakdale Affair.

The novel wraps up better than it should, considering the clumsy handling of the “mystery” aspects of the plot. Bridge and “the Kid” face getting strung up by a mob, and Bridge then acts as the detective who explains all the previous events in order to placate the crowd. A last minute rescue occurs, and Bridge ends up with the girl he’s been unknowingly protecting all this time.

Beppo, sadly, ends up dead with police shotgun shells in his furry hide. He earned his Frazetta cover painting, that’s for certain. Good bear, Beppo. Good bear.

* * * Spoilers Conclude * * *

As with most Burroughs novels of this period with a contemporary setting, the dialogue suffers from a surfeit of stylized slang. Most of it comes from the mouths of the Sky Pilot’s gang or in the “kiddie” argot of Willie Case. “Fertheluvomike!”, shouted by Columbus Blackie, is now one of my favorite oddball words to come from an ERB novel. I believe the Prussian army won a battle at that town in the Seven Years’ War.

The Oakdale Affair consists of one long chapter, and not for any good reason. I don’t know why Burroughs even decided to have a “Chapter One” heading at all, or why the editors at Blue Book kept it and added a note that it was the only chapter. There are few text breaks, all in the last quarter, to provide readers convenient stopping points, so the story misses an important rhythm that a long work needs. It also causes confusing, abrupt shifts in location and POV.

How did The Oakdale Affair end up as a movie a year after publication, and yet fans had to wait a century to get a movie of A Princess of Mars? I’ve failed to locate any copies or online versions of The Oakdale Affair, even short clips; it may be a “lost” film, like many from the silent era. (Only an hour survives of the first Tarzan film from 1917.) Since I haven’t seen The Oakdale Affair, I can’t speak to how well it uses Burroughs’s book. I can hazard the guess that The Oakdale Affair offered Hollywood a familiar format, the romantic crime melodrama, that could be turned around fast on a budget. The film rights went for a paltry $1,000, less than Burroughs got for either “Mucker” book on first magazine publication. Since The Mucker would have made a superb silent movie serial in the 1920s, it’s frustrating to know this minor spin-off with no exotic locations ended up getting made instead. A promotional blurb for the film indicates that it makes Abigail Prim (now just “Gail”) the main character and follows her running away from her family and joining “a band of tramps.” There’s no mention of the character Bridge, and his name isn’t on the IMDb cast list. How pointless: Bridge was the reason The Oakdale Affair was written in the first place! Hollywood was only interested in the book as means to create a “maiden in distress” story. “A mystery play for the average viewer!” proclaims the ad copy. Oh, goody… I’m going to go get in line right now.

How did The Oakdale Affair end up as a movie a year after publication, and yet fans had to wait a century to get a movie of A Princess of Mars? I’ve failed to locate any copies or online versions of The Oakdale Affair, even short clips; it may be a “lost” film, like many from the silent era. (Only an hour survives of the first Tarzan film from 1917.) Since I haven’t seen The Oakdale Affair, I can’t speak to how well it uses Burroughs’s book. I can hazard the guess that The Oakdale Affair offered Hollywood a familiar format, the romantic crime melodrama, that could be turned around fast on a budget. The film rights went for a paltry $1,000, less than Burroughs got for either “Mucker” book on first magazine publication. Since The Mucker would have made a superb silent movie serial in the 1920s, it’s frustrating to know this minor spin-off with no exotic locations ended up getting made instead. A promotional blurb for the film indicates that it makes Abigail Prim (now just “Gail”) the main character and follows her running away from her family and joining “a band of tramps.” There’s no mention of the character Bridge, and his name isn’t on the IMDb cast list. How pointless: Bridge was the reason The Oakdale Affair was written in the first place! Hollywood was only interested in the book as means to create a “maiden in distress” story. “A mystery play for the average viewer!” proclaims the ad copy. Oh, goody… I’m going to go get in line right now.

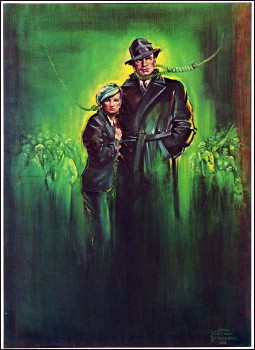

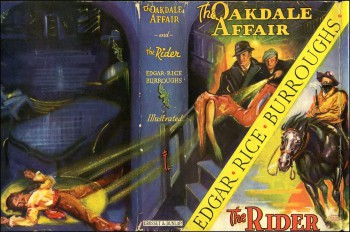

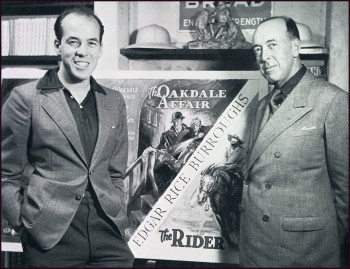

It took almost two decades for The Oakdale Affair to reach hardcover. ERB, Inc. released it in 1937 paired with H.R.H. The Rider (shortened to just The Rider), a serial also originally published in 1918. This edition was a milestone for ERB, Inc. since it was the first that John “Jack” Coleman Burroughs illustrated for his father. For the front piece, Jack Burroughs used his wife Jane Ralston and his sister’s husband James Pierce, who played Tarzan in the movie Tarzan and the Golden Lion in 1927, as the models. The result, seen at the top of the page, is a fantastic mood-drenched work, one of the best pieces Jack Burroughs produced for his father’s work.

For unexplained reasons, this first hardcover version cut off the last 174 lines of The Oakdale Affair. The story’s ending is comprehensible without them, but only barely, and their loss softens the impact of the coda and sublimates the romance to almost nothing. The lines were not restored until the Charter paperback in 1979. The first paperback from Ace Book sports the Frank Frazetta cover that boldly gives away the identity of the ghost of the Squibb’s house with its portrait of a fierce Beppo the Bear dragging chains. As Beppo is the best part of the shaky novel, Frank made the right choice giving him the lead.

Next time I visit with Mr. Burroughs, it will be to discuss his second novel, the one squeezed between the intros of John Carter and Tarzan: The Outlaw of Torn.

Ryan Harvey is a veteran blogger for Black Gate and an award-winning science-fiction and fantasy author who knows Godzilla personally. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his story “The Sorrowless Thief” appears in Black Gate online fiction. Both take place in his science fantasy world of Ahn-Tarqa. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, the prologue to the upcoming novel Turn Over the Moon, is currently available as an e-book. You can keep up with him at his website, www.RyanHarveyWriter.com, and follow him on Twitter.

[…] Harvey’s article on Edgar Rice Burroughs’ The Oakdale Affair, which went live less than an hour ago, was our […]

[…] so much that he fashioned a spin-off story a few years later featuring him as the protagonist: The Oakdale Affair. Expect to hear about that in a few weeks. Meanwhile, I’ve some giant monster […]