Poetry in Action: The Return of the Mucker by Edgar Rice Burroughs

This upfront: The Return of the Mucker is less effective a novel than last week’s topic, The Mucker. The strange genre-mashings of the first book give way to the more familiar settings of the American southwest and northern Mexico. The Return of the Mucker plays as an outright Western for most of its length, and offers nothing as lunatic as samurai cannibals. As a story, it doesn’t hold together as well as The Mucker, getting weighed down with too much plot “business” while the first book stripped away extraneous aspects the farther the story advanced until it came down to only the hero and heroine, Billy Byrne and Barbara Harding.

This upfront: The Return of the Mucker is less effective a novel than last week’s topic, The Mucker. The strange genre-mashings of the first book give way to the more familiar settings of the American southwest and northern Mexico. The Return of the Mucker plays as an outright Western for most of its length, and offers nothing as lunatic as samurai cannibals. As a story, it doesn’t hold together as well as The Mucker, getting weighed down with too much plot “business” while the first book stripped away extraneous aspects the farther the story advanced until it came down to only the hero and heroine, Billy Byrne and Barbara Harding.

Yet The Return of the Mucker is still a strong work that glosses over its shaky plot elements with a breakneck action finale, fitting developments of Billy Byrne’s personality that merge together his extremes, and one of Burroughs’s most intriguing characters: a hobo-poet hero named Bridge.

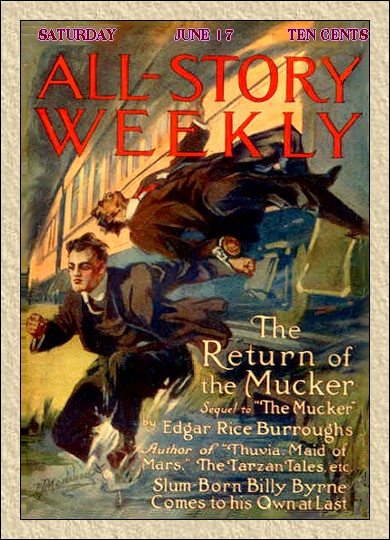

Burroughs’s working title for The Mucker’s sequel was Out There Somewhere, the name of a poem that inspired the character of Bridge. (More about that later.) Burroughs submitted the novel to All Story in March 1916, soon after completing it. Editor Thomas Newell Metcalf purchased the story immediately, and the first of five installments appeared two months later under its more marketable title. The Return of the Mucker was published in hardcover in 1921 from A. C. McClurg as Part II of a volume simply called The Mucker.

When the story begins, Billy Byrne is no longer “the mucker.” ERB makes that clear as a cloudless blue sky in the second paragraph: “Billy Byrne was no longer the mucker.” Barbara Harding cured Byrne of his criminal life and coarse ways: everything that defines the now outdated slang term “mucker.” But Billy Byrne surrendered his love for Barbara so she could marry William Mallory at the conclusion of the first book, and he’s now a man without direction — or a complete personality. If he isn’t the mucker, and he’s not with the woman who changed him, what is he?

Billy Byrne turns to his only option: clean up the unfinished business in his hometown of Chicago, where the false murder rap that made him flee the city in the first place still hangs over him. Barbara’s lessons drive him to return and seek justice. A train takes him back to where he started, and he fills “his lungs deep with the familiar medium which is known as air in Chicago.” (Burroughs makes certain from the start that readers know there’ll still be comedy in the book.)

It doesn’t end up as simple as planned. The police nab Byrne soon after he alights in Chicago. He is rapidly tried, found guilty of the original crime, and given a life sentence in Joliet. Byrne’s resentment and anger resurface; he may never be the mucker again, but he’s no coward and his hatred of the police won’t allow him to take this miscarriage of justice. On the train to Joliet, he breaks free and goes on the lam.

It doesn’t end up as simple as planned. The police nab Byrne soon after he alights in Chicago. He is rapidly tried, found guilty of the original crime, and given a life sentence in Joliet. Byrne’s resentment and anger resurface; he may never be the mucker again, but he’s no coward and his hatred of the police won’t allow him to take this miscarriage of justice. On the train to Joliet, he breaks free and goes on the lam.

On a journey toward Kansas, Byrne meets a fascinating character: Bridge. Not “Bridges.” Just “Bridge.” This hobo wanderer picked up the nickname as a shortened version of “Unabridged,” because of his use of long words. He’s a lover of poetry, although not skilled with making his own rhymes. “I’ve tried… but there always seems to be something lacking in my stuff — it don’t get under your belt — the divine afflatus is not there. I may start out all right, but I always end up where I didn’t expect to go, and where nobody wants to be.”

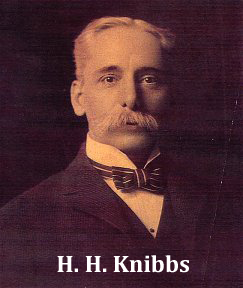

The poet Bridge quotes the most is Henry Herbert Knibbs (1874–1945), an American verse writer who seized Edgar Rice Burroughs’s attention a few year earlier. Knibbs is little known today — he doesn’t even have an individual Wikipedia entry — but he was an influential author of Western-themed poetry in the early decades of the twentieth century. His 1914 collection Songs of the Outlands: Ballads of the Hoboes and Other Verse features “Out There Somewhere,” the poem that so captivated Burroughs that he made it central to The Return of the Mucker and the character of Bridge. The second and third stanzas of the poem, which ERB does not use in the novel, appear to be the inspiration for the character:

He must have been a college guy, for he was talking big and high, —

The trees were standing all around as silent as a church —

A little closer I saw he was manufacturing poetry,

Just like a Mocker sitting on a pussy-willow perch.I squatted down and rolled a smoke and listened to each word he spoke;

He never stumbled, reared or broke; he never missed a word,

And though he was a Bo like me, he’d been a gent once, I could see;

I ain’t much strong on poetry, but this is what I heard…

Bridge often sings of “Penelope” from the Odyssey (although through quotes from “Out There Somewhere”) and this becomes a parallel to Byrne and his love for Barbara, even though he knows nothing of the story of the Odysseus trying to find his way home.

Bridge makes the observation about the strange changes in Byrne’s speech that readers may have also wondered about:

“Why is it, Billy … That upon occasion you speak the king’s English after the manner of the boulevard, and again after that of the back alley? Sometimes you say ‘that’ and ‘dat’ in the same sentence. Your conversational clashes are numerous. Surely something or someone has cramped your original style.”

“I was born and brought up on ‘dat,’” explained Billy. “She taught me the other line of talk. Sometimes I forget. I had about twenty years of the other and only one of hers, and twenty to one is a long shot — more apt to lose than win.”

Bridge mentions that he was in the Yukon at some time, so it seems that there’s a bit of Jack London, another of Burroughs’s favorite authors, in the hobo poet. (For more about the connection between Knibbs and ERB, see this essay.)

Although a rough character, Bridge is another example of a “middle range” figure who hangs between the extremes of the corrupt rich and the lowlife criminal that was part of The Mucker’s story and Billy Byrne’s personal journey. As Byrne develops through the second novel, the name “Bridge” takes on an additional meaning: the character is a literal “bridge” bringing together the conflict of high class life and two-fisted bravado. Billy Byrne eventually becomes an integrated character, both the mucker and not the mucker at the same time, the kind of man who can be with Barbara Harding and yet ruthlessly deal with evil men. Bridge is the symbolic link between worlds, the sort of hero that Billy Byrne eventually becomes — even if he never fully picks up his friend’s love of poetry. He gets just enough, however.

Although a rough character, Bridge is another example of a “middle range” figure who hangs between the extremes of the corrupt rich and the lowlife criminal that was part of The Mucker’s story and Billy Byrne’s personal journey. As Byrne develops through the second novel, the name “Bridge” takes on an additional meaning: the character is a literal “bridge” bringing together the conflict of high class life and two-fisted bravado. Billy Byrne eventually becomes an integrated character, both the mucker and not the mucker at the same time, the kind of man who can be with Barbara Harding and yet ruthlessly deal with evil men. Bridge is the symbolic link between worlds, the sort of hero that Billy Byrne eventually becomes — even if he never fully picks up his friend’s love of poetry. He gets just enough, however.

After Byrne helps Bridge against a few ne’er do wells on the trails, the two of them hit together. But with a $5,000 reward out for Billy Byrne’s capture, it isn’t long before informers put Kansas City policeman Flannagan on his tail.

After escaping Flannagan in an exciting bar fight, Byrne and Bridge head for the Mexican border to find work. However, this was the mid-1910s, and Mexico was in the middle of a decade-long revolution. The bandit leader near the border, Pesita, sides with either rebel Francisco Pancho Villa or President Venustiano Carranza, depending on how it benefits him, and he especially detests Americans. Byrne and Bridge fall into the hands of one of Pesita’s bands, and so find themselves moving into the “Zapata Western” genre. (The name comes from a politically-charged subgenre of the Italian Western of the 1960s and ‘70s set during the Mexican Revolution; see A Bullet for the General and Duck, You Sucker! for prime examples.) This wilderness is more foreign to Billy Byrne than a Pacific island; it’s as far removed from the world he knows of city streets than anything else he’s encountered. Burroughs, however, knew this place well, having served in the 7th U.S. Cavalry in Arizona. ERB brings the same reality to this setting that he did with Chicago in The Mucker.

When Byrne and Bridges are brought before “General” Pesita, Bridge does some quick talking and tells the bandit leader that his friend’s odd dialect comes from the German colony of “Gran Avenue,” or “Granavenoo,” and he’s therefore not one of the hated Americanos. Pesita falls for it and makes Byrne a captain. Byrne immediately has to work against his new boss to keep Pesita from killing Bridge and a local caught with them, Miguel, whom Pesita believes is allied with Pancho Villa. (He’s right about that, by the way. It’s probably the only thing Pesita gets right during the whole book.)

At this point, the story begins to grow into tangles. Billy Byrne drifts in and out of working for Pesita, and Bridge hops around the story in a sometimes bewildering fashion. Of course, Barbara Harding returns in one of the coincidences that ERB loved to hurl into his tales. Barbara decided not to marry Billy Mallory in New York after all — leaving her romantic fate open — and decided to accompany her father Arthur Harding on a visit to El Orobo, a ranch he owns across the border. Unfortunately, they’ve arrived at a catastrophic time to be an American in Mexico. Arthur Harding has also hired the worst possible manager for El Orobo, an obnoxious anti-Mexican named Grayson, who will turn into one of the story’s major villains. Kidnappings, bank robberies, chases, romantic complications, revolutionary battles, gunfights, and general chaos ensue in northern Mexico.

As with the first book, quite a few villains move through the story: Pesita, Flannagan, Captain Ronzales, Esteban, Jose, and most memorably Grayson, the most interesting villain in both “Mucker” books. He’s a delightful lech. However, dominant bad guys were never an ERB specialty; I noticed throughout the Mars series that few remarkable villains appeared who lasted through an entire book. The best adversaries appear for only a few chapters until they are defeated, or else they eventually switch allegiances; Phaidor in The Gods of Mars and The Warlord of Mars is the best example of the latter. But at his finest, Burroughs doesn’t need such prominent villains. He focuses on his heroes and lets them carry the story as they overcome monsters, second-tier baddies, and romantic drama. The two “Mucker” books show how a pair of excellent leads, Billy Byrne and Barbara Harding — with the later addition of Bridge — could propel an action narrative on their own.

Burroughs assumes readers have some knowledge of the Mexican Revolution, which makes sense because at the time The Return of the Mucker was published, the revolution was the major foreign news story after the war in Europe. Burroughs wrote the novel in January–February of 1916, when Carranza was the president of Mexico and the Pancho Villa was resisting him in the north. The story doesn’t dwell on the politics of the revolution, which have little thematic relevance to Billy Byrne’s story (this isn’t a Euro-Western about a man awaking to revolutionary fervor) and would slow down the pace. Burroughs uses the invented character of Pesita as a self-interested bad guy who can turn any direction in the Mexican conflict as the plot requires. The text frequently mentions Pancho Villa, but he never steps onto the stage. This is for the best, since a major historical figure might unbalance the book and feel like a gimmick. Villa stays where he should: a threatening catalyst just out of sight. Pesita serves as his fictional stand-in, since he can come to an end free from the constraints of history. He also simplifies the conflict: essentially, he just hates Americans. The only reason he puts any trust in Billy Byrne is because of his unlikely belief the man comes from somewhere in Germany called “Granavenoo.” (A bit of Burroughsian humor that falls flat.)

Burroughs assumes readers have some knowledge of the Mexican Revolution, which makes sense because at the time The Return of the Mucker was published, the revolution was the major foreign news story after the war in Europe. Burroughs wrote the novel in January–February of 1916, when Carranza was the president of Mexico and the Pancho Villa was resisting him in the north. The story doesn’t dwell on the politics of the revolution, which have little thematic relevance to Billy Byrne’s story (this isn’t a Euro-Western about a man awaking to revolutionary fervor) and would slow down the pace. Burroughs uses the invented character of Pesita as a self-interested bad guy who can turn any direction in the Mexican conflict as the plot requires. The text frequently mentions Pancho Villa, but he never steps onto the stage. This is for the best, since a major historical figure might unbalance the book and feel like a gimmick. Villa stays where he should: a threatening catalyst just out of sight. Pesita serves as his fictional stand-in, since he can come to an end free from the constraints of history. He also simplifies the conflict: essentially, he just hates Americans. The only reason he puts any trust in Billy Byrne is because of his unlikely belief the man comes from somewhere in Germany called “Granavenoo.” (A bit of Burroughsian humor that falls flat.)

Barbara proves herself as tough as she was in the previous book: at one point, she has to come to Billy Byrne’s rescue, pulling herself through a raging river to bridle a horse and bring it where Byrne is imprisoned so he can escape. But Barbara gets her chance to be bait soon after when men working for Grayson kidnap her, triggering the massive finale.

The last three chapters of The Return of the Mucker are the definition of “whizbang action.” Billy Byrne with the companionship of a fellow named Eddie Shorter — whose mother’s life Byrne saved earlier — rescue Barbara from Grayson’s hired kidnappers in an intense shootout in the hills. Pesita and his men make a play to seize El Orobo Rancho while it’s under-defended, although the resistance turns fierce, thanks to Bridge flying to the rescue after he overheard Pesita’s plans. Furious action follows in a run toward the border with the Pesita’s followers behind and news of Pancho Villa ahead. There’s even a classic U.S. Calvary charge. It’s fantastic pulp fun, even without samurais.

Where The Mucker went for an intimate, character-centered finale, the sequel is all about ramping up to delirious heights and letting the new Billy Byrne cut loose. In his words he becomes “the mucker” again, but this is really the integrated Billy Byrne, a heroic fighter who knows what he’s fighting for.

This new thing surged through him and over him with all the blind, brutal, compelling force of a mighty tidal wave. It battered down and swept away the frail barriers of his new-found gentleness. Again he was the Mucker — hating the artificial wall of social caste which separated him from this girl; but now he was ready to climb the wall, or better still, to batter it down with his huge fists.

This is a different Billy, who may think of himself as the Mucker, but who has encountered this “new thing” from his time with Bridge that makes him a great pulp hero. He defends his friends and the love of his life while slaying enemies with his bare hands. Yes, the villains of the story receive some bloody (and bloody exciting) justice.

While Billy is a strong hero with a complicated character arc, Barbara is one of Burroughs’s greatest heroines. She does occasionally need to be rescued, but she does an astonishing amount of rescuing. The chapter where she goes on her own to break Byrne out of the ranch house where Grayson locked him up is one of the novel’s most suspenseful. Heroines in ERB are usually the objects of love/obsession/lust of most of the male characters, but in Barbara’s case, she earns the attraction of every man not only for her beauty, but for her strength and integrity. This is a woman who gutted the samurai leader who captured her in The Mucker — she’s an able protagonist in her own right, and never just a standard damsel in distress.

While Billy is a strong hero with a complicated character arc, Barbara is one of Burroughs’s greatest heroines. She does occasionally need to be rescued, but she does an astonishing amount of rescuing. The chapter where she goes on her own to break Byrne out of the ranch house where Grayson locked him up is one of the novel’s most suspenseful. Heroines in ERB are usually the objects of love/obsession/lust of most of the male characters, but in Barbara’s case, she earns the attraction of every man not only for her beauty, but for her strength and integrity. This is a woman who gutted the samurai leader who captured her in The Mucker — she’s an able protagonist in her own right, and never just a standard damsel in distress.

The romance conclusion to The Return of the Mucker is passionate, although unsurprising; it can’t compete with the semi-tragedy of the first book, but this is something The Return of Tarzan also had to deal with following the surprise coda of Tarzan of the Apes. But there’s no way I could call the ending of The Return of the Mucker a disappointment with all the frenetic action that ties together story strands that were too spread out earlier.

One bit of a letdown in the closing chapters is that Burroughs never finds a way to satisfactorily resolve the love triangle set up with Billy-Barbara-Bridge from Bridge’s point of view. However, the last moments of the book fall to Bridge… his story is poised to go on, and he knows it. And he knows the poetry to quote to show it.

The Return of the Mucker lacks the powerful unity of The Mucker, but no reader of Burroughs should miss it. The books are incompatible as a single novel the way A. C. McClurg published them, but Burroughs doesn’t disappoint following up on the possibilities of Billy Byrne. And Bridge is simply one of the most intriguing characters to appear in the early pulps. The Mucker and The Return of the Mucker put the lie to the criticism that ERB was only capable of plotting action-driven, superficial stories. The characterizations and themes of the books aren’t subtle, but lack of subtlety does not mean a work is simplistic. So many critics dismiss Burroughs because of this misunderstanding. The “Mucker” books form an essential part of the arsenal in the defense of Edgar Rice Burroughs as one of the twentieth century’s most important authors.

Burroughs enjoyed writing the character of Bridge so much that he fashioned a spin-off story a few years later featuring him as the protagonist: The Oakdale Affair. Expect to hear about that in a few weeks. Meanwhile, I’ve some giant monster manufacture-on-demand business to attend to….

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

Great write-up! Hmmm … Never read Oakdale Affair and didn’t realize it was connected. Someday I have to go back and read the rest of the Burroughs odds and ends.

[…] novel (40,000 words) titled “Bridge and the Oskaloosa Kid.” A reader of the previous year’s The Return of the Mucker might recognize the name “Bridge” as belonging to that novel’s itinerant poet and co-hero. […]