Torg and Marvel Super Heroes: The shared vocabulary of stories

John O’Neill’s editorial in Black Gate 14 touched on gaming, on wargaming and role-playing, and on the way these things shaped the way friends interact. It hit home for me, because I recognised in my life much the same sort of phenomenon John described in his own.

John O’Neill’s editorial in Black Gate 14 touched on gaming, on wargaming and role-playing, and on the way these things shaped the way friends interact. It hit home for me, because I recognised in my life much the same sort of phenomenon John described in his own.

I didn’t play Nova, the game he and many of his friends played as a sort of long-form creative wargaming campaign. I did play, and in one case referee, long-running role-playing campaigns that gave everybody who took part a special vocabulary, a shared set of touchstones and references that (I think) acquired a particular power from being our own: our own stories, independent from the culture at large, shaped by us and our choices.

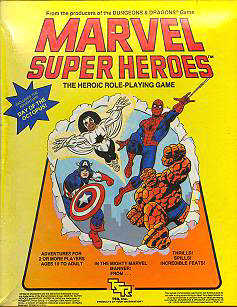

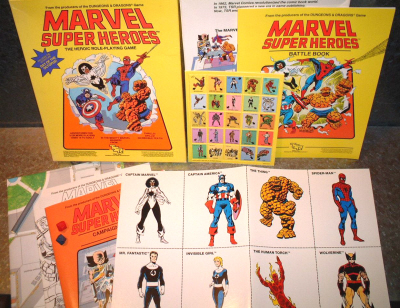

I was about seventeen when I met a group of role-playing gamers who’d created their own world for the Marvel Super-Heroes role-playing system. I think the game had been going on for something like eight years at the point I met them, and it’s still going today. (Jeff Grubb has a thoughtful reminiscence on the secret origins of MSH here.)

The world, as such, was not and is not stable; it has been re-invented several times over, as campaigns and storylines begin and end (and, this being a super-hero game, occasionally lead to a reboot of the timeline in the course of play), sometimes incorporating actual comic-book characters and sometimes not, but always using many of the same heroes and villains created by our group of gamers.

The characters were, are, the essence of the game; not their histories, but their concepts, and if you played in that world you could add something to it that would become a part of the ongoing tale.

For example, I once played a character called the Red Ensign, heroic defender of Canada. I first imagined him as a Canadian Superman, given vast powers by an illicit American intelligence program operating on Canadian soil so that they could use Canadians for their test subjects instead of risking American lives (a take on the CIA-funded MKULTRA experiments at McGill University).

Since that time, though, he’s popped up in variety of different ways, whether played by me, by someone else, or used by the referee as an NPC. He’s been a 1940s crimebuster in a Golden Age campaign, for example, and I’m told that the current campaign, set in the 1980s, features him as an archery-based hero.

Since that time, though, he’s popped up in variety of different ways, whether played by me, by someone else, or used by the referee as an NPC. He’s been a 1940s crimebuster in a Golden Age campaign, for example, and I’m told that the current campaign, set in the 1980s, features him as an archery-based hero.

The variations are potentially infinite; the concept, the archetype, of the ultimate Canadian hero plays out differently in different campaigns.

I think this became a feature of our group of friends, as we moved around, drifted away, and then returned and caught up on the current campaign, and heard what was happening not only with the players but with their characters. The characters were fluid counterparts of the real people, objective correlatives for the players.

The villains and supporting characters as well; they took shape in game after game, campaign after campaign, and we knew who they were, we knew what they meant, we knew who were the master villains and who were the mooks and who were trusted allies (mostly; sometimes a referee would trick us). The characters we created meant as much to us, then, as the characters in the worlds of entertainment around us.

Which was on one level thrilling. But with a different game, I was able to find a different level entirely.

John wrote that “we played games because they fueled our imaginations,” and I found that particularly true with one long-running campaign I ran in a now perhaps largely unknown system.

John wrote that “we played games because they fueled our imaginations,” and I found that particularly true with one long-running campaign I ran in a now perhaps largely unknown system.

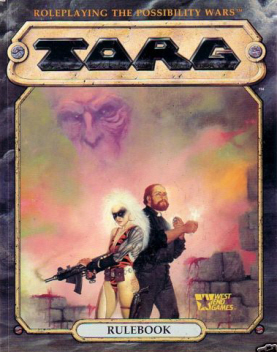

Torg was a product of West End games; the name was originally an acronym for ‘That Other Role-playing Game’, as the then-nameless system was under development as West End’s Star Wars game.

The idea of the game was that a number of extradimensional bad guys, the High Lords, were striving to become Torg — essentially, God. To do this the baddies needed to find and raid a dimension filled with ‘possibility energy,’ which turned out to be our world, ‘Core Earth’.

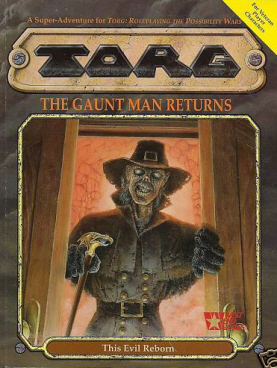

But Earth was so strong in energy that if any one High Lord tried to invade, the backlash would destroy him. So the most fearsome of the High Lords, the Gaunt Man, formed an uneasy alliance with his greatest rivals to drain the planet — with each High Lord planning to backstab the others as the dimension’s energy was drained.

But the energy backlash was still a problem; instead of destroying the High Lords, the energy empowered ordinary men and women in Core Earth and in the High Lord’s own dimensions, turning them into heroes to fight the High Lords’ evil.

The players took on the roles of these heroes, waging a long-standing ‘Possibility War’ against the invaders.

Oh — and each High Lord came from a dimension that represented a different genre of fiction. They way they invaded was by imposing their reality on different parts of the Earth.

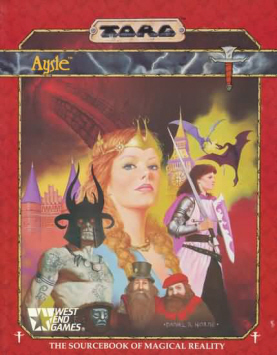

So England, Ireland, and Scandinavia were filled with dragons and elves, France was taken over by a cyberpunk theocracy, Japan became a land of ninjas, spies, and bleeding-edge technology, and a fascist empire led by a hooded madman ruled among the pyramids of Egypt.

So England, Ireland, and Scandinavia were filled with dragons and elves, France was taken over by a cyberpunk theocracy, Japan became a land of ninjas, spies, and bleeding-edge technology, and a fascist empire led by a hooded madman ruled among the pyramids of Egypt.

The Gaunt Man himself ruled a realm of Victorian Horror that took over Indonesia, a deliberate ploy by the game’s creators to bring in the racial and gender fears that provided the subtext to much Victorian horror.

Each of the realities had slightly different rules so that each area had a different feel; but as the game progressed, elements from different realities mingled more and more frequently.

If you ever wanted to see a cybernetic elven ninja werewolf, Torg was the game for you.

But I think what really made the game work for me as a referee was the firm distinction it made between ‘standard’ and ‘dramatic’ scenes. In standard scenes, heroes were able to show off their special abilities and fight their way through armies. In dramatic scenes, the climax of an adventure, or of a major movement within an adventure, everything was much more difficult.

Combat results were more likely to be dangerous to heroes. Things were more likely to go wrong. It was harder to defuse a bomb, or save the innocent victim from the death-trap.

Basically, what Torg did was hard-wire drama into the rules. That made for a powerful experience; as a referee, I saw the dramatic arc of an adventure playing out in front of me.

I was a part of it, in fact. I began to feel, on a very basic level, how stories came together. I believe the same thing was true of the players, and I think this helped make Torg the experience it was.

I’ve seen a number of other games try to do the same thing, but have yet to find one where the integration of drama into a rules system feels as thoroughly natural as in Torg.

I’ve seen a number of other games try to do the same thing, but have yet to find one where the integration of drama into a rules system feels as thoroughly natural as in Torg.

I think the reason is that, on a fundamental level, Torg was actually about stories and storytelling. The meta-story of the game had the earth under attack by stories — by genres. On the one hand, the vast amount of possibility energy on Earth represented the ability of life to transcend genres, or move easily from one genre to another; on the other, it became clear at a certain point that the ‘Core Earth’ of the Torg game was itself meant to represent the ‘Core Earth’ of fiction, not of reality.

At the end of the day, the players fought the High Lords by telling stories — by doing great deeds, the retelling of which would plant a new spark of possibility energy within the people who heard the tales.

With story at the core of the game, it only made sense that the actions of the characters would take the shape of stories.

The possibility energy that made the player characters heroes was, in essence, imagination. Torg, as a game, was literally driven by imagination on numerous different levels.

And that was a powerful stimulus. While those Marvel games drew power from the constant reinvention of archetypal characters, archetypes that had particular meaning to us, Torg was a single campaign that developed over time.

Before the internet was broadly popular, West End tried to allow the war to take shape through reports sent in by players running campaigns all around the world, collating events to try to create a consensus for how the war developed; you didn’t have to hew close to the ‘official’ campaign that resulted, but I found that keeping the timeline vaguely current with the ‘official’ campaign meant that you could use the twists West End introduced to their concept into your own game.

The result was that players came and went, but the overall story went on and on, gaining in richness and history. We never quite finished the war, but the epics we created still have some resonance for me.

The result was that players came and went, but the overall story went on and on, gaining in richness and history. We never quite finished the war, but the epics we created still have some resonance for me.

For those of us who played the game long enough, it became a part of our vocabulary. It mimicked genre fiction so well we could easily watch a movie and see it playing out according to Torg rules; we could tell when the dramatic scenes had started.

I think something similar happened with the Marvel games — you couldn’t help but read comics differently when you were helping create super-hero adventures yourself. Which, so often, seemed superior to what was being published by the major publishers, especially in the early 1990s.

As John said, reflecting on the power of the story of the Nova games: “I know my opinion is clouded because those dramas involved me and the people I loved, but I know I’m not completely wrong either.”

Finally, when all’s said and done, I recognise in my life much the same phenomena that wore away at John’s game of Nova: the slow encroachment of other concerns, of jobs and families and old friends moving away. Life is in constant motion, and sometimes games aren’t adaptable enough to survive changing situations.

I will note that things are better in one way; girls now are much more likely to be gamers, even compared to when I was younger. There’s no longer always the choice between relationships and gaming. Instead, gamer couples now, I think, gain something in their relationship from sharing a hobby.

Things change, and evolve. Some of the old gaming group are still in my life; and there are new friends I’ve met over time, with new imaginations and new stories to tell.

That’s probably how it’s going to be for the foreseeable future. The people we game with may change, our stories may change as a result, but the impulse to play with our imaginations is constant. There’s a new Marvel campaign going on. And at some point, some time to come, I will restart the Possibility Wars.

And this time, I mean to see them through to the end.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His blog is Hochelaga Depicta.

I was huge in MSH in high school. Aside from D&D it was my game of choice. I still remember all of the stats (Feeble, Poor, Typical, etc…), and most of the stats for my favorite characters.

TORG was a friend of mine’s favorite. I played a few games of that too. Interesting system, though I still preferred MSH. 😀

[…] of the Aztecs, Middle Earth, Jack Vance’s Dying Earth, Judge Dredd’s Mega-City One, the Marvel Universe… heck, there were even role playing games about high school, fer cryin’ out […]