A Superior Confection: Robert A. Heinlein’s The Pursuit of the Pankera

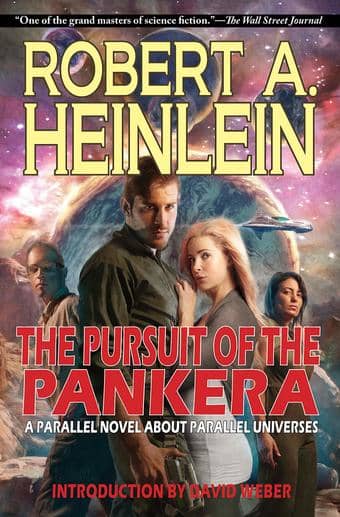

The Pursuit of the Pankera

The Pursuit of the Pankera

By Robert A. Heinlein

Caezik (503 pages, $29.99 hardcover, $9.99 digital, March 2020)

Cover by Scott Grimando

It’s almost impossible to discuss Robert A. Heinlein’s The Pursuit of the Pankera: A Parallel Novel about Parallel Universes without revealing and thus spoiling the plot devices of it and its 1980 prequel/sequel, The Number of the Beast—. Heinlein, first Grand Master of the SFWA, for decades acclaimed as the Dean of sf, no longer pleases everyone. Some readers, especially academic critics, have denounced both books as grossly self-indulgent and even worthless. Others, like the brilliant Marxist professor H. Bruce Franklin (in his important 1980 study Robert A. Heinlein: America as Science Fiction) catch the feel of Beast: “a cotton-candy apocalypse — frothy, sweet, airy, mellow, light, festive, whimsical, insubstantial” (199).

That final word is unjust, since many pages are devoted to an investigation of lifeboat rules, and what Algis Budrys termed “protocol,” capable of mutual acceptance by four genius-level libertarians, two of them women, one the daughter of crusty and irritable Professor Jake Burroughs used to having his own way. Oh, plus an increasingly intelligent and willful computer in the younger man’s flying car, uplifted to true personhood during a visit to… The Land of Oz. This jolly and quite necessary absurdity is a side effect of their discovery that the world is built of myth, of fictons, yielding a kind of “pantheistic multiperson solipsism” occasioned by the dreams, terrors and wishes (as it were) of writers and readers. (Regrettably, Heinlein’s term ficton is “corrected” to fiction in Pankera.)

Robert Heinlein, it follows, is the god (or demon) of the universes the four learn how to visit in Jake’s continua craft. Some of these worlds he had written himself (especially the history of near-immortal Lazarus Long and his incestuous mother and clone daughters, or would write later. Others are the creations of other major writers such as Edgar Rice Burroughs (Tarzan, John Carter of Mars), L. Frank Baum (Oz), Heinlein’s older friend E.E. “Doc” Smith, whose inaugural space opera sequence tracks the psionic Lenses gained by eugenic human warrior-saints, chess pawns in a cosmic war between aliens billions of years older than humankind.

Forty years ago, therefore, I was surprised and rather disappointed that the early Mars segment in The Number of the Beast— was not set in the Burroughs universe, even though the younger male is named Zebadiah John Carter, and his new wife Deety née Burroughs is named for Dejah Thoris, the red-skinned egg-laying wife of the “fictional” John Carter of Virginia, eventually Warlord of Mars. And why was the Lensmen universe barely touched beyond what seemed a rather snooty use of Lensman “Ted Smith”? I speculated that Heinlein had in fact developed these possibilities in an original draft, but had been forced by copyright restrictions to ditch them and develop drastically different tropes. But aside from that unconfirmed blockage, several late-life tragedies afflicted Heinlein.

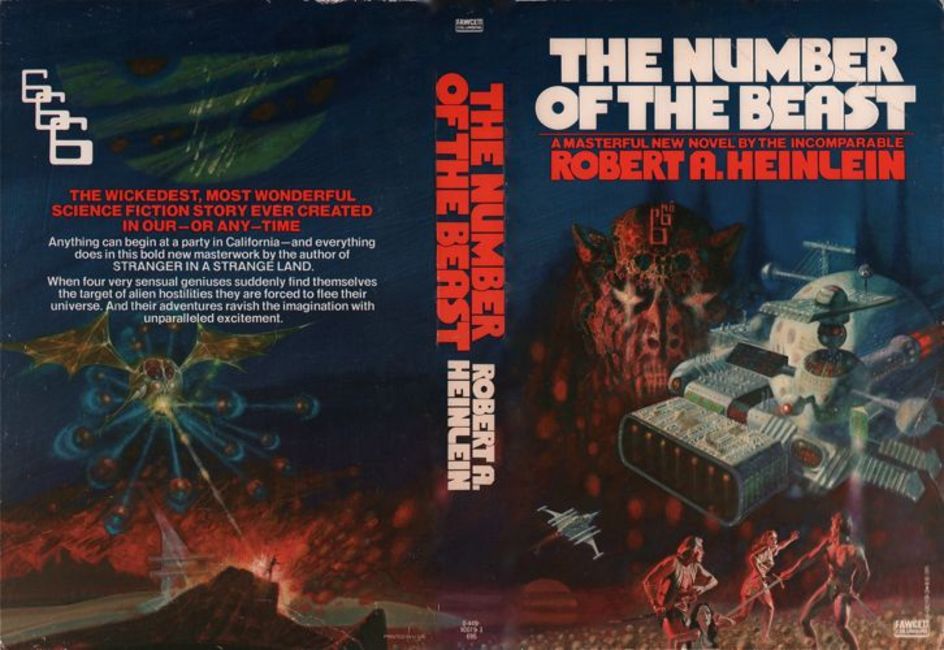

The Number of the Beast, trade paperback edition. Fawcett, 1980. Cover by Richard Powers.

An expert in his oeuvre, James Gifford of the nicely named nitrosyncretic.com, notes that

In 1970, he was stricken with a serious case of peritonitis that very nearly ended his life. He was unable to write for almost two full years following. At the time he was hospitalized, he had just completed the first draft of I Will Fear No Evil. With Heinlein gravely ill and unable to make business decisions, his wife and agent elected to publish the book in its unedited form.

That decision is generally regarded as ill-advised, and probably played a major role in blocking a new novel drafted in 1977. As an invited speaker in 1979 to a joint hearing by the House Select Committees on Aging and on Science and Technology, Heinlein laid out in horrid detail how, as he and his wife walked at the end of 1977 on the beach in Moorea, Tahiti, a carotid blockage triggered a transient ischemic attack. For months, despite emergency diagnoses and treatment, the blood flow to his brain was constricted.

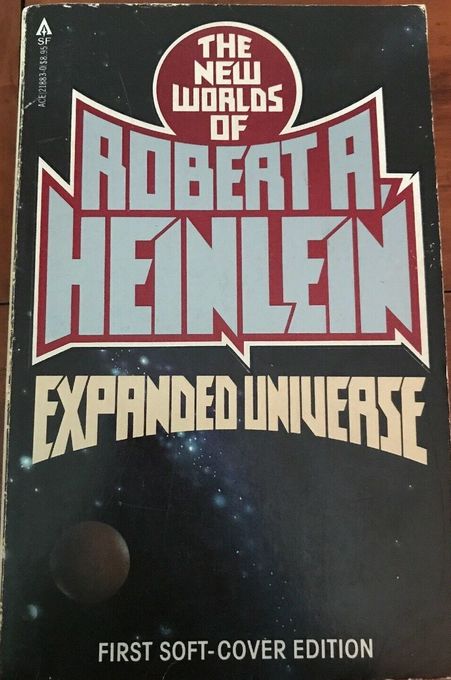

In “Spinoff,” the speech he gave to the Committees (in Expanded Universe, Ace 1980), he explained the cruel effects of this brain damage: “No wonder I was dopey — could not write, could not study, could not read anything difficult” (507). In a four hour operation using then-advanced instrumentation, a right brain artery was redirected to oxygenate his left brain functions, specifically his verbal regions. He told the Committee members: “I’ve been out of convalescence about one year,.. I’m working, too; I have completed writing a very long novel and am about halfway through another book” (510).

|

|

Expanded Universe trade paper edition (Ace Books, 1981)

Bearing in mind that this was mid-July, 1979, and The Number of the Beast— was first published just on a year later, we must assume that Heinlein had completed the revision and extension when his brain came back fully online, following his wife Virginia’s decision not to allow publication of what is now known as The Pursuit of the Pankera. This is not entirely consistent with Gifford’s summary of the first draft: “written in 1975. This was at the nadir of Heinlein’s battle with the carotid blockage that was interfering with his mental acuity…”

Heinlein testified in “Spinoff,”

Fourteen months ago my brain was dull-normal and getting worse, slipping toward ‘human vegetable.’ I slept 16 hours a day and wasn’t worth a hoot the other eight” (505).

On the basis of such rumors and reports, I had concluded that a book written before the operation must be unpublishably dire. So I was astonished at how readable and complex the recovered text is. (The publisher refers to some lost sections having been found and inserted, but claims that no significant new material was used, but I see little evidence of this.) Some portions of the Martian idyll drag their bare feel a bit, and one suspects that the hand is the hand of the brain-weakened Heinlein even though the voice is the voice of the younger wunderkind of the 1940s and ’50s. The transition from the complex monster-hunting of the first third of the novel to the frank silliness of first encounters with four-armed Martian Tharks and their thoat steeds might provoke some thoat-clearing (that sort of shameless punning, yes).

But the development of this earlier narrative is superior to the hijinks of The Number of the Beast—, where most of the Black Hat Bad Guy aliens bear names that jumble the letters in Heinlein’s own name, or a few of his friends (and perhaps otherwise: a Black Hat named L. Ron O’Leemy is easily identified as one of Heinlein’s early friends and rivals in the pulp fiction era). The first disguised alien is Professor Neil O’Heret Brain, easily decoded as Robert A. Heinlein. A card notes the names “Hernia, Lien” which is “R. A. Heinlein.” Others cavort. Most of these games are absent from the early version, but what is of some note is the extent to which cheesy or even somewhat sexist exchanges are gone from the Pankera version, or perhaps were never there in the first place.

Perhaps the oddest aspect is precisely the careful scissoring of material that might provoke outrage among those who are outraged by stuff like this (from the opening page of Beast, where the wealthy young former military/space pilot Zeb dances ballroom with the lovely Deety, who irritates him by declaring that “He’s a Mad Scientist and I’m his Beautiful Daughter.” Zeb waltzes on “while taking another look down her evening formal. Nice view. Not foam rubber… A perfect partner — as long as she didn’t talk.” Several paragraphs later:

I openly stared. ‘Is that cantilevering natural? Or is there an invisible bra, you being in fact the sole support of two dependents?’ She glanced down, looked up and grinned. ‘They do stick out, don’t they?’

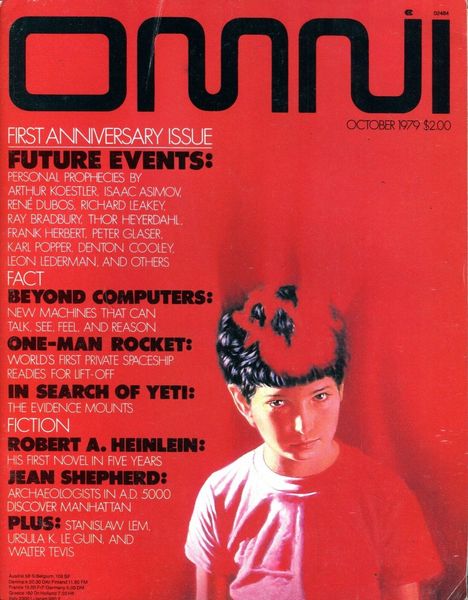

And so on. Now the interesting aspect here is that the opening “Not foam rubber” remains in Pankera but the rest is absent. By chapter IV, some blather about “teats” being the correct word for the objects sticking out is gone. This is either microsurgery, carefully scalpeled and repositioned, or Heinlein failed to think of the gags until he was patching up the start of Beast and aiming, let’s say, at the young male readers of Playboy. (The big segment that opens the book was published in two chunks in Omni, the popsci companion of Penthouse.)

|

|

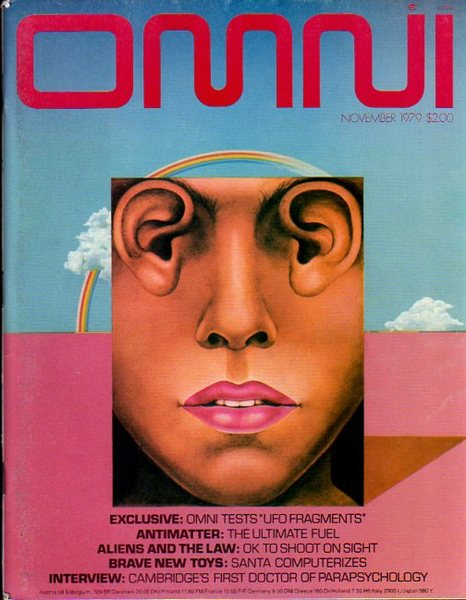

Omni magazine, October and November 1979, with a 2-part excerpt of

The Number of the Beast. Covers by Peter Caras and Ute Osterwalder.

In short, it just is not the case, as we are subtly led to believe, that this substantial section of both books is identical. No, it’s bowdlerized. Does that matter? Up to each reader, I guess. But I should mention as well the odd blurb that promotes the recovered edition (covered jacket):

Heinlein’s audacious experiment… One of the most audacious experiments ever done in science fiction by the legendary author of the classic bestseller, Starship Troopers.

The new subtitle sets up this sleight of hand: A Parallel Novel about Parallel Universes.

Nice try, people, but not true. Heinlein and his wife agreed that it was botched, and declined to submit it for publication. Some time later, as his faculties came back into play (and perhaps confronted by copyright issues), he either decided to solve the latter by deleting the Burroughs material and most of the Smith Lensmen, or was drawn to the World as Myth substructure and rebuilt much of the final two-thirds.

Does this distinction matter? Perhaps not. Because finally, the disinterment of this mid-1970s confection should be welcomed by most Heinlein fans, who will agree with Tor.com reviewer Alan Brown (April, 2020): “In my opinion, it’s far superior to the version previously published.” While I might not put it that strongly, I did enjoy reading the book and warmly recommend it to fans of the first Grand Master. Good times!

……………………………………

References:

Alan Brown: Long-Lost Treasure (Tor.com: April, 2020)

Algis Budrys: Reviews, Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (October, 1980)

H. Bruce Franklin: Robert A. Heinlein: America as Science Fiction (Oxford University Press, 1980)

James Gifford: https://www.nitrosyncretic.com/rah/rahfaq.html#0105

Robert A. Heinlein: “Spinoff” (in Expanded Universe, Ace 1980)

Robert A. Heinlein: two-part serialization of The Number of the Beast— (Omni, Oct and Nov, 1979)

Robert A. Heinlein: The Number of the Beast— (New English Library, 1980)

Robert A. Heinlein: The Pursuit of the Pankera: A Parallel Novel about Parallel Universes (Caezik, March 2020)

An Australian living in Texas with his American wife for nearly 20 years, Damien Broderick, PhD, is a writer and literary theorist who has published 75 books, some with co-writers and co-editors. In 2005, he received the Distinguished Scholarship Award of the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts. In 2020, his Springer non-fiction book /The Time Machine Hypothesis /was shortlisted for a Locus award. His forthcoming novel /The Kingdom of the Worlds/, an authorized collaboration with the late John Brunner,//will be published in the UK by Orion.

I’d bought this after seeing the cover pictured somewhere and reading the accompanying article about why it hadn’t been published years ago (I thought it was here at Black Gate, but I can’t find a previous reference to it). I’d read “The Number of the Beast” in 1980, but frankly remembered little about it. Since I own copies of almost everything Heinlein wrote (though there’s much I have yet to read), I went ahead and bought the book in late March and started reading it almost immediately. As I read, what I did remember about Heinlein’s later work was exactly what Alan Brown’s Tor article mentioned: a lot of attention to sexual matters, or at least a great deal of casual nudity. I was born in 1950, so I lived through the “swingin’ ’60s” and the “Summer of Love” and all that, but I was also raised Catholic, and recall how awkward I felt in my first high school gym class, showering afterward with a dozen of my male classmates. I didn’t marry until I was 40, and there’s no way I’d have felt comfortable being nude with my father-in-law. Like Brown, I found that creepy. But what disappointed me more initially was alluded to in Broderick’s article here: the material that takes the four main characters to fictional worlds. When I realized they were on the Mars invented by ERB (and I’d read all of those years ago), I suddenly found myself feeling cheated, and losing interest. I did something I almost NEVER do: I put the book down and didn’t finish it. Between setting it aside in early April and finally picking it back up last week, I’d read quite a few other books, and decided to give Heinlein’s another look. Much to my surprise, I got interested once the quartet moved to another parallel universe — even though it was also fictional. And then I understood more of what Heinlein was doing (yes, I CAN be slow on the uptake). I haven’t read any of L. Frank Baum, and only one of “Doc” Smith’s Lensman books, but I did find the second half of “The Pursuit of the Pankera” worth the time. Though I still much prefer early Heinlein to his later efforts, I am glad I read this most recently published work. Now I’m eager to go back to “The Number of the Beast” and make comparisons.

I confess my less than thrilled memories of THE NUMBER OF THE BEAST, plus the notion that this might have been the crappier early version of a novel I didn’t like all that much when “fixed”, had led me to decide not to read this. But you make a convincing case, Damien, that THE PURSUIT OF THE PANKERA is worth a try! Damn you — it’s not like my TBR pile needed another book on top of its already teeetering spire!

I must confess to being one of those troglodytes who find the latter Heinlein (say, anything after The Moon is a Harsh Mistress) completely unreadable. The sermonizing, solipsism, and moral coarseness that in his greatest work were held in check by that tremendous narrative gift take over completely and nothing is left but tedium and shamanism. I’m sure that on some levels this is an “interesting” read, but I’d rather just reread Double Star or Have Spacesuit, Will Travel.

“L. Ron O’Leemy” is an anagram of Lyle Monroe (one of Heinlein’s pseudonyms), as well as a reference to L. Ron Hubbard.